Etrurian-Shangean War: Difference between revisions

Britbong64 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

|||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

Military modernisation was the most impressive of the Emperor's efforts but had been fraught with difficulties. Under the Toki Xiaodong had no organised national army - it instead had an elite, all-Senrian force headquartered in Rongzhuo controlled by the central government and a series of armies within the provinces. The provincial armies were the responsibility of provincial governors who could be ordered to mobilise them by the central government in wartime but other then that were administratively separate from central government authority. This led to provincial governors to often act as ''de facto'' {{wp|warlord}}s leading autonomous armies. Under the Xiyong Emperor, the best units from the previous Toki army as well as various provincial armies were merged into a single national army consisting of around 100,000 men. The provincial army system was abolished - the country was instead divided into seven military governates (headquartered in Lukeng, Baiqiao, Caozhou, Shenkong, Kongyu, Rongzhuo and Yinbao) which consisted of several provinces. In the event of a war the national army could order the mobilisation of militias within these governates who would function as a ''de facto'' {{wp|reserve army}}. Although these militias were less well trained or armed then the national army, they were nevertheless more standardised then the old provincial armies being commanded by professional officers rather then provincial governors. The governate militia's were created to ensure that Xiaodong could muster its large population in a war whilst maintaining a more central albeit smaller professional core. {{Wp|Conscription}} was also introduced although its implementation was patchy. | Military modernisation was the most impressive of the Emperor's efforts but had been fraught with difficulties. Under the Toki Xiaodong had no organised national army - it instead had an elite, all-Senrian force headquartered in Rongzhuo controlled by the central government and a series of armies within the provinces. The provincial armies were the responsibility of provincial governors who could be ordered to mobilise them by the central government in wartime but other then that were administratively separate from central government authority. This led to provincial governors to often act as ''de facto'' {{wp|warlord}}s leading autonomous armies. Under the Xiyong Emperor, the best units from the previous Toki army as well as various provincial armies were merged into a single national army consisting of around 100,000 men. The provincial army system was abolished - the country was instead divided into seven military governates (headquartered in Lukeng, Baiqiao, Caozhou, Shenkong, Kongyu, Rongzhuo and Yinbao) which consisted of several provinces. In the event of a war the national army could order the mobilisation of militias within these governates who would function as a ''de facto'' {{wp|reserve army}}. Although these militias were less well trained or armed then the national army, they were nevertheless more standardised then the old provincial armies being commanded by professional officers rather then provincial governors. The governate militia's were created to ensure that Xiaodong could muster its large population in a war whilst maintaining a more central albeit smaller professional core. {{Wp|Conscription}} was also introduced although its implementation was patchy. | ||

Xiaodongese military modernisation however received a big boost when General [[Sotirien Desjardins]] arrived on a [[Gaullica|Gaullican]] military mission in 1878. The Xiaodongese admired the Gaullican army and were keen to copy it, modelling their new system of conscription and military schools on the Gaullican method. General Desjardins was able the spearhead the reorganisation of the command structure into divisions and regiments and overhauled the system of logistics, transportation, and structures to increase mobility. Desjardins's influence also secured Xiaodong purchasing of the {{Wp|Fusil Gras mle 1874|Modèle 74}} rifle from Gaullica. By the outbreak of hostilities in 1886 the Xiaodongese army | Xiaodongese military modernisation however received a big boost when General [[Sotirien Desjardins]] arrived on a [[Gaullica|Gaullican]] military mission in 1878. The Xiaodongese admired the Gaullican army and were keen to copy it, modelling their new system of conscription and military schools on the Gaullican method. General Desjardins was able the spearhead the reorganisation of the command structure into divisions and regiments and overhauled the system of logistics, transportation, and structures to increase mobility. Desjardins's influence also secured Xiaodong purchasing of the {{Wp|Fusil Gras mle 1874|Modèle 74}} rifle from Gaullica. By the outbreak of hostilities in 1886 the Xiaodongese army was considered to be the most modernised amongst the southern Coian nations of Xiaodong, [[Kuthina]] and [[Senria]] albeit still lagging behind its Euclean and Asterian counterparts. | ||

Xiaodong during this period also embarked on naval modernisation, although this was slower then army modernisation. Xiaodong had two fleets - for the Hongcha basin and Bay of Bashurat - but only one battleship, the Yuanjin, docked in Baiqiao. Xiaodongese admirals favoured the ''{{Wp|jeune école}}'' naval doctrine which emphasised the use of cruisers and torpedo boats to harass and combat larger fleets as well as disrupt trade due to the presence of several, much larger navies in the region. | Xiaodong during this period also embarked on naval modernisation, although this was slower then army modernisation. Xiaodong had two fleets - for the Hongcha basin and Bay of Bashurat - but only one battleship, the Yuanjin, docked in Baiqiao. Xiaodongese admirals favoured the ''{{Wp|jeune école}}'' naval doctrine which emphasised the use of cruisers and torpedo boats to harass and combat larger fleets as well as disrupt trade due to the presence of several, much larger navies in the region. | ||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

=== Etruria === | === Etruria === | ||

=== Xiaodong === | === Xiaodong === | ||

[[File:General Chanzy.jpg|thumb|[[Gaullica|Gaullican]] {{wp|general officer|general}} [[Sotirien Desjardins]] spearheaded the modernisation of Xiaodong's army.|200px]] | |||

Since beginning military modernisation in the 1860's Xiaodong had undergone a revolution in military terms. The adoption of Euclean drill, tactics and organisation was implemented in the 1870's under a military mission led by [[Sotirien Desjardins]] and his deputy [[Guillaime de Learé]] who implemented a widescale reorganisation of the Xiaodongese army in almost every respect introducing a system of divisions and regiments to boost mobility, placing more focus on the army's transportation and logistical system and establishing artillery and engineering regiments under independent commands. Desjardins also emphasised the connections of Xiaodong's seven major military bases by railway but with the Xiaodongese rail system being underdeveloped in the 1880's this idea was still in its infancy in 1886. | |||

By the start of the war in 1886 de Learé estimated that the Xiaodongese army counted some 163,500 men organised into sixteen divisions each consisting roughly 10,200 men split two infantry brigades of two infantry regiments of three infantry battalions (7,200), an artillery regiment of twenty-four guns (180), a cavalry regiment of ten squadrons (2,000), an engineer battalion of four companies (400) and a transport battalion of four companies (400). However there was wide differences between the quality of each division with some better trained in army drill then others. The 42,000 strong Third Army was widely considered to be the best trained and equipped army in Xiaodong and amongst south Coian nations as a whole, with de Learé describing it "''as worthy for combat as any Euclean army - perhaps not of Gaullican or Weranian stock, but certainly sufficient to beat a bestial Soravian or slovenly Estmerish''". | |||

However, whilst the regular army had undergone intense modernisation the same could not be said for the regional militia's that underpinned Xiaodongese military policy. These militia's were poorly equipped and trained, being at best a {{Wp|gendarmerie}} force. Whilst the regular army was almost entirely armed with some form of {{wp|rifle}} it was estimated that up to 60% of all militia members were not armed with rifles or muskets, instead wielding a variety of variety of swords, spears, pikes, halberds, and bows and arrows. As de Learé wrote in his report to the Gaullican Army at the outbreak of war; ''"of the militias, I have nothing to say other then they are what is expected of Coians. They are a dreadfully armed rabble whose existence serves to only drain supplies and equipment from the rather impressive regulars''". | |||

The Xiaodongese military's greatest weakness was its equipment and logistical problems. The regular army suffered some problems garnering a consistent stream of equipment, although by the 1880's these problems had begun to dissipate as Xiaodong moved increasingly to producing its own variants of the Modèle 74 rifle and its own artillery, the Jianxing gun. By 1886 a member of the Gaullican military mission lieutenant Marcel Saint-Yves noted that "''the greatest deficit the regulars find themselves in is uniforms - which is amongst the fairest of problems to confront''". Saint-Yves noted however that the underdeveloped rail network "''severely limits the mobility of the Xiaodongese army''" and like de Learé concurred that the militia's were "''at best, an unneeded indulgence and at worst actively malicious to the ability of Xiaodong to prosecute a war''". | |||

[[File:1908年荫昌等人校阅秋操.jpg|thumb|250px|Generals of the Second Army performing {{wp|war game}}s in 1885, wearing a mixture of traditional and Euclean-inspired uniforms.|left]] | |||

Nevertheless, the Gaullicans were more-or-less impressed with the Xiaodongese military leadership whom de Learé called "''on the whole excellent staff planners and seemingly aware of the great difficulties their military faced''". Xiaodongese military strategy was largely determined by [[Zhang Haodong]], the key military adviser to the Xiyong Emperor. Zhang's overall strategy in the event of a Euclean invasion was to raise the militia's to force the Euclean army into fighting a {{Wp|Attrition warfare|war of attrition}}, during which Xiaodong would mobilise its regular army and deliver a ''{{wp|coup de grâce}}'' through a series of decisive victories. | |||

Key to this strategy was the acceptance of use of {{Wp|human wave attack}}s and high casualty rates amongst militia troops. Zhang admitted that his strategy would incur large losses of life for Xiaodongese forces but reasoned that as militia forces were usually badly led, had poor morale and often paid late by provincial governments that they would be unreliable and so their commanders had to use simple tactics that emphasised a maximum concentration of force to work within his grand strategy. Zhang's plans were considered generally to apply to the west of the country where railway networks were most developed and where an Euclean attack was most expected - the investment of railways and detailed mobilisation plans in the Kaoming peninsula were credited as key to Xiaodongese success during the later war. | |||

[[File:Dingyuen1.jpg|thumb|250px|The {{Wp|Ironclad warship|ironclad battleship}} ''Yuanjin'', the flagship of the Heavenly Navy.]] | |||

The Xiaodongese navy had less investment then the army but was considered to be more generally modernised. The navy was also modelled after its Gaullican counterpart, although Xiaodong failed to secure a generous naval training programme as it had done the army from Gaullica. The Xiaodongese navy was split into two fleets - the Hongcha and Bashurat Fleets - with the Bashurat Fleet based in Lunkeng led by Xiang Liuxian. General Xiaodongese naval strategy was based on the {{wp|jeune école}} doctrine with Xiaodongese naval planners not hoping to be able to defeat Euclean battles in a conventional naval battle but rather to disrupt them long enough to deny them the ability to resupply colonial armies, thereby enabling the Xiaodongese army to defeat land forces and force a peace treaty on the enemy via a victory by ''{{wp|fait accompli}}''. | |||

Naval strategy however was hampered by the fact that most naval tactical books were written in {{Wp|French language|Gaullican}}, which only a fraction of senior naval officers were familiar with. Training manuals had begun to be translated in 1884 under the command of Admiral Xiang (who spoke fluent Gaullican) but this process was only partially implemented by the time war broke out in 1886. The majority of ships in the navy had been purchased from [[Werania]] and Gaullica before the war - according to one estimate, half of the entire Xiaodongese navy had been brought from Gaullica over 1877-1886 and assembled in Xiaodong. | |||

The Xiaodongese navy was less confident then the army of victory when war was declared, with Admiral Xiang reportedly bursting into tears when he heard the news. Prior to the Etrurian declaration of war the majority of the Hongcha fleet - including the flagship ''Yuanjin'' - was transferred to the Bashurat fleet out of the fear of the Etrurian navy, whilst the government confiscated many civilian vessels to use as {{Wp|Auxiliary ship|auxiliaries}}. | |||

== Etrurian attack on Meixiang == | == Etrurian attack on Meixiang == | ||

Revision as of 01:51, 30 January 2021

| Etrurian-Xiaodongese War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

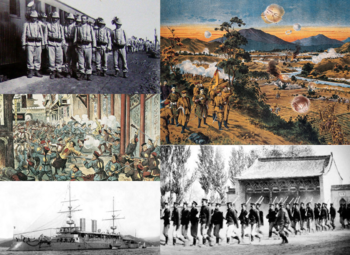

Clockwise from top left

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

760,000 (total)

|

171,493 (total)

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

40,000-60,000 killed ~100,000 died of wounds or disease Total: 140,000-160,000 |

23,830 killed ~39,650 died of wounds or disease Total: 63,480 | ||||||

The Etrurian-Xiaodongese War (Vespasian: Guerra Etruriana-Hiautungese; Xiaodongese 饿唾利亚战争, Ètuòlìyǎ Zhànzhēng "Etrurian War") was a war fought between Xiaodong and Etruria for a little over a year from 1886 to 1888 over ownership of the Kaoming peninsula in Xiaodong. The war was predominantly fought on the Kaoming peninsula and in the Bay of Bashurat in Xiaodong. The direct cause of the war was a dispute over the so-called "neutral zone" between the Etrurian concession of Kaoming (modern day Gaoming) and Xiaodong, but it was motivated by growing Etrurian encroachment over Xiaodong that sought to expand further into the Kaoming peninsula and Chanwa as well as rising Xiaodongese nationalism that resented the continuation of unequal treaties with Euclean powers such as Etruria.

The Etrurian annexation of Kaoming in 1858 and its assumption of suzerainty over Kumuso afterwards led to an increasing sense in Xiaodong of Etrurian encroachment of Xiaodong, especially as Etruria further colonised much of Satria giving it a large degree of control of the Bay of Bashurat. Xiaodongese leaders saw an Etrurian annexation or vassalisation of Senria and the Kaoming peninsula as highly likely and began resisting further Etrurian domination of the area via its own annexations of Dakata and Chanwa and a vigorous modernisation of its military.

The Etrurian monarchy under Caio Augustino had faced persistent unpopularity for years, especially under the unpopular premiership of Girolamo Galba. The Etrurian government believed that a war with Xiaodong would easily result in an Etrurian victory failing to recognise the rapid modernisation Xiaodong had embarked on since the 1870's and that a successful annexation of the Kaoming peninsula would undermine Gaullica's presence in the Bay of Bashurat (exercised through Sangte and Jindao) as well as reviving the flagging popularity of the Etrurian monarchy.

In October 1886 the Etrurian governor of Kaoming General Elladio Augusto di Darbomida claimed that Xiaodong had persistently violated the demilitarised neutral zone between the Etrurian concessions of Kaoming and Porto Iagiano (Port Haijian) and demanded that Xiaodong cede the neutral zone directly to Etruria as well as approve of the creation of an Etrurian protectorate in the peninsula to assure the interests of Etruria in the region. Xiaodong offered to cede the neutral zone but refused to approve of the creation of a protectorate; on the 7 November 1886 Etruria performed a surprise attack on the Xiaodongese city of Meixiang from Kaoming, quickly seizing the city. The two sides subsequently declared war on each other.

The war was hotly contested on the Kaoming-Wangzhuang railway, with Etrurian military strategy being to seize the city of Wangzhuang thereby cutting the Kaoming peninsula off from the rest of Xiaodong and increasing the Kaoming Army's ability to supply itself during the war. The Etrurian government expected the Xiaodongese to be poorly armed and trained and so sent little supplies to either the Kaoming Army or Bashurat fleet. The Etrurian advance into Xiaodong was much slower and more difficult then was anticipated by Etrurian generals, suffering several major defeats by more numerous Xiaodongese forces.

In the summer of 1887 Etruria attempted to deliver a knock-out blow to Xiaodongese forces by winning a decisive naval engagement in the Bay of Bashurat before landing in the city of Lukeng and cutting off Xiaodongese forces from the north of the peninsula. Whilst Etruria would win the Battle of the Bay of Bashurat destroying much of the Xiaodongese fleet they suffered heavy casualties and were forced to land on the much less defensible town of Jungfa. The Battle of Jungfa between Xiaodongese and Etrurian forces saw the Etrurians decisively defeated mainly by the Gaullican trained and equipped Third Army. Following the Battle of Jungfa Etrurian forces were pushed back by Xiaodong's advance as the war became more and more unpopular in Etruria. By February 1888 Etrurian forces had been pushed back to Kaoming, with Xiaodong occupying the neutral zone and Porto Iagiano whilst laying siege to Kaoming. The winter of 1887-1888 saw disease spread in Kaoming that sapped morale and in February the city surrendered to Xiaodongese forces.

The subsequent peace treaty saw Etruria agree to hand over Porto Iagiano to Xiaodong as well as sell its shares to Xiaodong in the Kaoming-Wangzhuang railway. Xiaodong was also granted the right to militarise the neutral zone and cancelled all prior treaties with Etruria in exchange for recognising a new lease of 70 years for the territory of Kaoming. The Xiaodongese acceptance of continued Etrurian ownership of Kaoming was seen as a way to save face for Etruria, whose humiliating defeat to a Coian country was one of the reasons for the San Sepulchro Revolution a month later that deposed the Etrurian monarchy and led to the Etrurian Second Republic.

The victory of a Coian power over a Euclean one was considered to be a major event in south Coius, inspiring anti-colonial movements as well as consolidating Xiaodong as a great power. The success of Xiaodongese forces led Gaullica in particular to increasingly to court Xiaodong culminating with the Entente alliance between the two in 1922.

Background

Etrurian colonialism in Xiaodong

Xiaodongese modernisation

Following the war with the Euclean powers in 1858 reformists in Xiaodong began to increasingly agitate for the overthrow of the Toki dynasty. Despite attempting to reform both conservative and revolutionary forces frustrated the increasing declining dynasty leading in 1860 to the Restoration War. Concluding in 1864 the war saw Toki Hayato, the last Toki emperor, flee into exile to be replaced by Yao Qinghong who became known as the Xiyong Emperor who declared the Heavenly Xiaodongese Empire. The Xiyong Emperor was supported by a mixture of reformist bureaucrats and military officers inspired by the Euclean model of development, traditionalists who resented the reforms attempted by Toki Hayato, nationalists who called for an end to foreign concessions, the Zohist clergy who wanted to return to their premier position in society after a period of decline under the Toki and Sotirians who wished for the new regime to allow them greater liberty in proselytising. The Xiyong Emperor was instinctively a reformist nationalist, but was mindful of conservative opposition and so sought to juggle between the factions.

Shortly into his reign the Xiyong Emperor launched the Great Cultural Rectification Movement (大文化整风运动; dà wénhuà zhěngfēng yùndòng) commonly known as the "Zhengfeng" (Rectification) which aimed to rapidly modernise and industrialise Xiaodong. The main early component of this was military modernisation - the Xiyong Emperor made sure following his victory over the Toki to abolish the old system of regional militaries and centralise into a single army, the Heavenly Army of Xiaodong. The successful modernisation of the military over the emperors early rule led to further reforms, such as industrialising Xiaodong predominantly through foreign investment from Euclean nations and the consolidation of capital into industrial conglomerates, implementing wide-reaching land reform, building railroads, abolishing slavery and institute a "Xiaocisation" policy for minorities. These reforms were increased following the Jiangxu Incident when conservatives attempted to and failed to overthrow the Emperor in a palace coup, although as a result the Emperor became more autocratic in his governing style coming to rely more on Zohist and nationalist elements.

Military modernisation was the most impressive of the Emperor's efforts but had been fraught with difficulties. Under the Toki Xiaodong had no organised national army - it instead had an elite, all-Senrian force headquartered in Rongzhuo controlled by the central government and a series of armies within the provinces. The provincial armies were the responsibility of provincial governors who could be ordered to mobilise them by the central government in wartime but other then that were administratively separate from central government authority. This led to provincial governors to often act as de facto warlords leading autonomous armies. Under the Xiyong Emperor, the best units from the previous Toki army as well as various provincial armies were merged into a single national army consisting of around 100,000 men. The provincial army system was abolished - the country was instead divided into seven military governates (headquartered in Lukeng, Baiqiao, Caozhou, Shenkong, Kongyu, Rongzhuo and Yinbao) which consisted of several provinces. In the event of a war the national army could order the mobilisation of militias within these governates who would function as a de facto reserve army. Although these militias were less well trained or armed then the national army, they were nevertheless more standardised then the old provincial armies being commanded by professional officers rather then provincial governors. The governate militia's were created to ensure that Xiaodong could muster its large population in a war whilst maintaining a more central albeit smaller professional core. Conscription was also introduced although its implementation was patchy.

Xiaodongese military modernisation however received a big boost when General Sotirien Desjardins arrived on a Gaullican military mission in 1878. The Xiaodongese admired the Gaullican army and were keen to copy it, modelling their new system of conscription and military schools on the Gaullican method. General Desjardins was able the spearhead the reorganisation of the command structure into divisions and regiments and overhauled the system of logistics, transportation, and structures to increase mobility. Desjardins's influence also secured Xiaodong purchasing of the Modèle 74 rifle from Gaullica. By the outbreak of hostilities in 1886 the Xiaodongese army was considered to be the most modernised amongst the southern Coian nations of Xiaodong, Kuthina and Senria albeit still lagging behind its Euclean and Asterian counterparts.

Xiaodong during this period also embarked on naval modernisation, although this was slower then army modernisation. Xiaodong had two fleets - for the Hongcha basin and Bay of Bashurat - but only one battleship, the Yuanjin, docked in Baiqiao. Xiaodongese admirals favoured the jeune école naval doctrine which emphasised the use of cruisers and torpedo boats to harass and combat larger fleets as well as disrupt trade due to the presence of several, much larger navies in the region.

Etrurian domestic crises

Key to the immediate outbreak of hostilities were the numerous domestic crises gripping Etruria by the late 1880s. Though the monarchy since its restoration across united Etruria in 1810 had overseen and led Etruria into becoming a great power and constructed one of the largest colonial empires, it had suffered a legitimacy deficit across much of society. Imprisoned by the constitutional order, and unable to remove the republican ideals that had become engrained from the Etrurian Revolution and the Etrurian First Republic, the monarchy was often forced to reply upon grand gestures and events as a means of beating back resurgent waves of republicanism. The need for grand achievements or events was one of the biggest drivers of Etrurian colonialism during the 19th century, which in turn came to be driven by rivalries with other major colonial powers, notably Gaullica and Estmere.

The immediate crisis sparking the conflict began in 1882 with the coronation of Caio Augustino as King, at only age 17, he was far from a capable needed to preserve his family’s position of power. However, the crisis surrounding the monarchy began two months later with the appointment of Girolamo Scalba as Premier. Scalba, who dominated the Etrurian historic right through his Constitutional Rights Party, was an authoritarian and corrupt individual. Scalba’s experience enabled him to manipulate the young king in supporting his endeavours, both legal and otherwise. As Scalba’s popularity began to decline rapidly in the 1880s, so too did support for the monarchy, which was seen to be complicit in Scalba’s unconstitutional behaviour. Desperate to use a traditional tool of his family, King Caio Augustino proposed a foreign conflict, which would reinvigorate the monarchy’s position. While it is widely accepted that if the King had removed Scalba as Premier, the crisis around his throne would have dissipated, the King by 1886 had come to rely on Scalba almost exclusively.

Another key catalyst for the pursuit of foreign conflict for domestic ends, came with 1885 and the emergence of peasant-based opposition to continued industrialisation. While many landed elites in rural Etruria condemned the monarchy’s embrace of the new industrialist class, the urban poor were becoming ever more critical of the monarchy over the squalid conditions found in Etrurian cities. The urban poor also faced near non-existence rights in the workplace and repeated calls for the end of child labour were blocked by Scalba.

Desperate to redeem the monarchy, the King joined with Scalba; who in turn sought a glorious victory to beat back rising working and peasant class opposition to his premiership, to orchestrate a swift victory that would expand Etruria’s colonial domain and display to the other great powers, Etruria’s military prowess and capabilities.

Di Darbomida claims

Military disposition prior to the conflict

Etruria

Xiaodong

Since beginning military modernisation in the 1860's Xiaodong had undergone a revolution in military terms. The adoption of Euclean drill, tactics and organisation was implemented in the 1870's under a military mission led by Sotirien Desjardins and his deputy Guillaime de Learé who implemented a widescale reorganisation of the Xiaodongese army in almost every respect introducing a system of divisions and regiments to boost mobility, placing more focus on the army's transportation and logistical system and establishing artillery and engineering regiments under independent commands. Desjardins also emphasised the connections of Xiaodong's seven major military bases by railway but with the Xiaodongese rail system being underdeveloped in the 1880's this idea was still in its infancy in 1886.

By the start of the war in 1886 de Learé estimated that the Xiaodongese army counted some 163,500 men organised into sixteen divisions each consisting roughly 10,200 men split two infantry brigades of two infantry regiments of three infantry battalions (7,200), an artillery regiment of twenty-four guns (180), a cavalry regiment of ten squadrons (2,000), an engineer battalion of four companies (400) and a transport battalion of four companies (400). However there was wide differences between the quality of each division with some better trained in army drill then others. The 42,000 strong Third Army was widely considered to be the best trained and equipped army in Xiaodong and amongst south Coian nations as a whole, with de Learé describing it "as worthy for combat as any Euclean army - perhaps not of Gaullican or Weranian stock, but certainly sufficient to beat a bestial Soravian or slovenly Estmerish".

However, whilst the regular army had undergone intense modernisation the same could not be said for the regional militia's that underpinned Xiaodongese military policy. These militia's were poorly equipped and trained, being at best a gendarmerie force. Whilst the regular army was almost entirely armed with some form of rifle it was estimated that up to 60% of all militia members were not armed with rifles or muskets, instead wielding a variety of variety of swords, spears, pikes, halberds, and bows and arrows. As de Learé wrote in his report to the Gaullican Army at the outbreak of war; "of the militias, I have nothing to say other then they are what is expected of Coians. They are a dreadfully armed rabble whose existence serves to only drain supplies and equipment from the rather impressive regulars".

The Xiaodongese military's greatest weakness was its equipment and logistical problems. The regular army suffered some problems garnering a consistent stream of equipment, although by the 1880's these problems had begun to dissipate as Xiaodong moved increasingly to producing its own variants of the Modèle 74 rifle and its own artillery, the Jianxing gun. By 1886 a member of the Gaullican military mission lieutenant Marcel Saint-Yves noted that "the greatest deficit the regulars find themselves in is uniforms - which is amongst the fairest of problems to confront". Saint-Yves noted however that the underdeveloped rail network "severely limits the mobility of the Xiaodongese army" and like de Learé concurred that the militia's were "at best, an unneeded indulgence and at worst actively malicious to the ability of Xiaodong to prosecute a war".

Nevertheless, the Gaullicans were more-or-less impressed with the Xiaodongese military leadership whom de Learé called "on the whole excellent staff planners and seemingly aware of the great difficulties their military faced". Xiaodongese military strategy was largely determined by Zhang Haodong, the key military adviser to the Xiyong Emperor. Zhang's overall strategy in the event of a Euclean invasion was to raise the militia's to force the Euclean army into fighting a war of attrition, during which Xiaodong would mobilise its regular army and deliver a coup de grâce through a series of decisive victories.

Key to this strategy was the acceptance of use of human wave attacks and high casualty rates amongst militia troops. Zhang admitted that his strategy would incur large losses of life for Xiaodongese forces but reasoned that as militia forces were usually badly led, had poor morale and often paid late by provincial governments that they would be unreliable and so their commanders had to use simple tactics that emphasised a maximum concentration of force to work within his grand strategy. Zhang's plans were considered generally to apply to the west of the country where railway networks were most developed and where an Euclean attack was most expected - the investment of railways and detailed mobilisation plans in the Kaoming peninsula were credited as key to Xiaodongese success during the later war.

The Xiaodongese navy had less investment then the army but was considered to be more generally modernised. The navy was also modelled after its Gaullican counterpart, although Xiaodong failed to secure a generous naval training programme as it had done the army from Gaullica. The Xiaodongese navy was split into two fleets - the Hongcha and Bashurat Fleets - with the Bashurat Fleet based in Lunkeng led by Xiang Liuxian. General Xiaodongese naval strategy was based on the jeune école doctrine with Xiaodongese naval planners not hoping to be able to defeat Euclean battles in a conventional naval battle but rather to disrupt them long enough to deny them the ability to resupply colonial armies, thereby enabling the Xiaodongese army to defeat land forces and force a peace treaty on the enemy via a victory by fait accompli.

Naval strategy however was hampered by the fact that most naval tactical books were written in Gaullican, which only a fraction of senior naval officers were familiar with. Training manuals had begun to be translated in 1884 under the command of Admiral Xiang (who spoke fluent Gaullican) but this process was only partially implemented by the time war broke out in 1886. The majority of ships in the navy had been purchased from Werania and Gaullica before the war - according to one estimate, half of the entire Xiaodongese navy had been brought from Gaullica over 1877-1886 and assembled in Xiaodong.

The Xiaodongese navy was less confident then the army of victory when war was declared, with Admiral Xiang reportedly bursting into tears when he heard the news. Prior to the Etrurian declaration of war the majority of the Hongcha fleet - including the flagship Yuanjin - was transferred to the Bashurat fleet out of the fear of the Etrurian navy, whilst the government confiscated many civilian vessels to use as auxiliaries.