Etrurian-Shangean War: Difference between revisions

Britbong64 (talk | contribs) |

Britbong64 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 163: | Line 163: | ||

The contradictory stance of the Shangean government and their comparative military passivity made the Etrurian government and the colonial office more receptive to militarily enforcing their demands over Shangea. With the Etrurian War Conference earlier in the year having decided to prosecute war against Shangea, a casus belli arranged and Shangea dithering in the face of diplomatic pressure the Etrurian government approved of the imminent commencement of hostilities. | The contradictory stance of the Shangean government and their comparative military passivity made the Etrurian government and the colonial office more receptive to militarily enforcing their demands over Shangea. With the Etrurian War Conference earlier in the year having decided to prosecute war against Shangea, a casus belli arranged and Shangea dithering in the face of diplomatic pressure the Etrurian government approved of the imminent commencement of hostilities. | ||

Although Etruria had planned to go to war with Shangea for several months it had not communicated this information to other Euclean nations. The ultimatum to create a protectorate over Kaoming came as a surprise to Euclean capitals who did not affirm support for the Etrurian expedition. | |||

== Course of the conflict == | == Course of the conflict == | ||

Revision as of 02:00, 3 December 2022

| Etrurian-Shangean War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

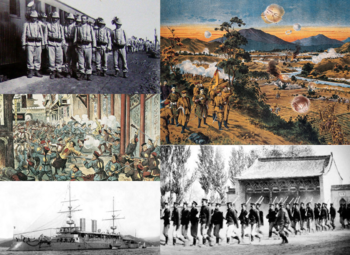

Clockwise from top left

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

760,000 (total)

|

171,493 (total)

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

40,000-60,000 killed ~100,000 died of wounds or disease Total: 140,000-160,000 |

23,830 killed ~39,650 died of wounds or disease Total: 63,480 | ||||||

The Etrurian-Shangeaese War (Vespasian: Guerra Etruriana-Shangean; Shangeaese 饿唾利亚战争, Ètuòlìyǎ Zhànzhēng "Etrurian War") was a war fought between Shangea and Etruria for a little over a year from 1886 to 1888 over ownership of the Kaoming peninsula in Shangea. The war was predominantly fought on the Kaoming peninsula and in the Bay of Bashurat in Shangea. The direct cause of the war was a dispute over the so-called "neutral zone" between the Etrurian concession of Kaoming (modern day Gaoming) and Shangea, but it was motivated by growing Etrurian encroachment over Shangea that sought to expand further into the Kaoming peninsula and Chanwa as well as rising Shangeaese nationalism that resented the continuation of unequal treaties with Euclean powers such as Etruria.

The Etrurian annexation of Kaoming in 1858 and its assumption of suzerainty over Kumuso afterwards led to an increasing sense in Shangea of Etrurian encroachment of Shangea, especially as Etruria further colonised much of Satria giving it a large degree of control of the Bay of Bashurat. Shangeaese leaders saw an Etrurian annexation or vassalisation of Senria and the Kaoming peninsula as highly likely and began resisting further Etrurian domination of the area via its own annexations of Dakata and Chanwa and a vigorous modernisation of its military.

The Etrurian monarchy under Caio Augustino had faced persistent unpopularity for years, especially under the premiership of Girolamo Scalba. The Etrurian government believed that a war with Shangea would easily result in an Etrurian victory failing to recognise the rapid modernisation Shangea had embarked on since the 1870's and that a successful annexation of the Kaoming peninsula would undermine Gaullica's presence in the Bay of Bashurat (exercised through Sangte and Jindao) as well as reviving the flagging popularity of the Etrurian monarchy.

In October 1886 the Etrurian governor of Kaoming General Elladio Augusto di Darbomida claimed that Shangea had persistently violated the demilitarised neutral zone between the Etrurian concessions of Kaoming and Porto Iagiano (Port Haijian) and demanded that Shangea cede the neutral zone directly to Etruria as well as approve of the creation of an Etrurian protectorate in the peninsula to assure the interests of Etruria in the region. Shangea offered to cede the neutral zone but refused to approve of the creation of a protectorate; on the 7 November 1886 Etruria performed a surprise attack on the Shangeaese city of Meixiang from Kaoming, quickly seizing the city. The two sides subsequently declared war on each other.

The war was hotly contested on the Kaoming-Wangzhuang railway, with Etrurian military strategy being to seize the city of Wangzhuang thereby cutting the Kaoming peninsula off from the rest of Shangea and increasing the Kaoming Army's ability to supply itself during the war. The Etrurian government expected the Shangeaese to be poorly armed and trained and so sent little supplies to either the Kaoming Army or Bashurat fleet. The Etrurian advance into Shangea was much slower and more difficult then was anticipated by Etrurian generals, suffering several major defeats by more numerous Shangeaese forces.

In the summer of 1887 Etruria attempted to deliver a knock-out blow to Shangeaese forces by winning a decisive naval engagement in the Bay of Bashurat before landing in the city of Lukeng and cutting off Shangeaese forces from the north of the peninsula. Whilst Etruria would win the Battle of the Bay of Bashurat destroying much of the Shangeaese fleet they suffered heavy casualties and were forced to land on the much less defensible town of Jungfa. The Battle of Jungfa between Shangeaese and Etrurian forces saw the Etrurians decisively defeated mainly by the Gaullican trained and equipped Third Army. Following the Battle of Jungfa Etrurian forces were pushed back by Shangea's advance as the war became more and more unpopular in Etruria. By February 1888 Etrurian forces had been pushed back to Kaoming, with Shangea occupying the neutral zone and Porto Iagiano whilst laying siege to Kaoming. The winter of 1887-1888 saw disease spread in Kaoming that sapped morale and in February the city surrendered to Shangeaese forces.

The subsequent peace treaty saw Etruria agree to hand over Porto Iagiano to Shangea as well as sell its shares to Shangea in the Kaoming-Wangzhuang railway. Shangea was also granted the right to militarise the neutral zone and cancelled all prior treaties with Etruria in exchange for recognising a new lease of 70 years for the territory of Kaoming. The Shangeaese acceptance of continued Etrurian ownership of Kaoming was seen as a way to save face for Etruria, whose humiliating defeat to a Coian country was one of the reasons for the San Sepulchro Revolution a month later that deposed the Etrurian monarchy and led to the Etrurian Second Republic.

The victory of a Coian power over a Euclean one was considered to be a major event in south Coius, inspiring anti-colonial movements as well as consolidating Shangea as a great power. The success of Shangeaese forces led Gaullica in particular to increasingly to court Shangea culminating with the Entente alliance between the two in 1922.

Background

Etrurian colonialism in Shangea

Etrurian colonial rivalries in southern Coius

Etrurian domestic crises

Etruria had been governed under a constitutional monarchy since the Caltrini Restoration in 1810, which replaced the revolutionary Etrurian First Republic with the United Kingdom of Etruria. Despite the restoration of monarchy, republican ideals and the principles ingrained across society during the First Republic remained stubbornly steadfast, despite the best efforts of the monarchy to promote a paternalistic relationship between monarch and subject. As such, throughout the 19th century, the Etrurian monarchy was forced to rely upon grandiose actions, policies, and propagations of Etrurian nationalism to ensure the same republican ideals did not boil over into revolution for a second time.

By the 1820s, the Etrurian monarchy had introduced and embraced a policy of “Imperial Republicanism” (Repubblicanesimo Imperiale), in which the monarchy would concede to elements of republicanism within the kingdom in exchange for its own privileges, customs and powers. Imperial Republicanism also predicated upon the ideal that “Etrurian imperialism of the Coian landmass would only but confirm for posterity and prosperity, the achievements made by the Royal House and its subjects.” Further to this was the monarchy’s useage of Solarian history to boost popular support and imaginations, in 1841, King Caio Onorio was crowned king and had “Successor of All Solarian Emperors” (Successore di tutti gli Imperatori Solariani) added to his titles and propagated personally, the claim that the Restoration was the “will of God, to see in Etruria, the successors of all Emperors restore in this world, the might and glory of Solaria” The pursuit of overseas dominions from then on took the propagandised form of “restoring Solaria in Etruria.” This was only an effort in national mobilisation to support the monarchy’s need to sustain the support of key commercial and aristocratic circles. Many of Etruria’s prominent landed families held strong links to the former First Republic and with it, the ideals, and principles it produced. Fearing the elite would facilitate the overthrow of the monarchy, successive Kings from 1810 onward, would support and promote colonialism as a means of opening markets for their erstwhile elite allies. From the coronation of King Caio Onorio in 1841, Etruria took to colonialism with a higher degree of aggression and urgency compared to the other major colonial powers. Having secured footholds in the decaying Gorsanid Empire, from the 1840s through to the 1860s, it rapidly conquered the Irfanic empire and consolidated its holdings in Satria. In 1860, King Caio Aurelio III proclaimed the “Instrument of Dominion”, formally organising the Etrurian colonial empire into three Dominions and several protectorates. This also came at a time of limited territory for further expansion, diminishing the monarchy’s reliance upon Imperial Republicanism.

Despite attempts at further expansion through the Etruro-Estmerish Wars in the late 1860s and 1870s, the allure and popularity of Imperial Republicanism was waning rapidly. Etrurian industrialisation by the early 1880s was provoking social upheaval the monarchy failed to appreciate and saw rising tensions both among the peasantry and urban poor. Etruria’s industrial cities were growing at passes that exceeded the logistical ability to feed the populations, housing and working conditions were among the worst in Eastern Euclea and growing mistreatment by the landed aristocracy toward farm labourers and leaseholders was provoking sporadic riots and clashes.

In 1882, Caio Augustino, was coronated king at age 17, the same year Giosuè Antonio Galba was appointed Prime Minister. Galba, a wealthy factory owner opposed any reforms aimed at improving working conditions and held authoritarian ambitions. Galba was able to swiftly dominate and manipulate the young King, who regularly issued royal decrees to protect Galba and support his unconstitutional power grabs. By 1885, Galba’s network of allies and enforcers across Etruria was fuelling a rise of republicanism, led by the San Sepulchro Society and Cardinal Romolo Alessandri. Galba, fearful of Alessandri leading the SSS into the 1886 election sought to use war to avoid a poll, owing to the 1863 Law that mandated no election be held during wartime. The King for his part was cognisant of rising tensions was too fearful that Galba’s unconstitutional and dictatorial behaviour would bring down the monarchy, support war as a means of shoring up Imperial Republicanism and the monarchy’s popular support.

Within months of the war’s beginning, Cardinal Alessandri was speaking regularly before crowds of thousands, condemning Galba, the poverty and stark class differences of the nation and declared his intention to lead a coalition of republican parties into the election. Galba, according to documents from the time, was swift to convince the King that if Alessandri won the election, he would have the royal household arrested and executed in honour of the Pantheonisti, who led the First Republic. In one letter he to the King he described Alessandri as a the “hound Francesco Aurelio Cacciarelli reborn, who seeks to tear your family limb from limb, less there be war to save us from the baying pack of wolves at our doors.” The King gave his approval of conflict, though he was not consulted on whom Etruria would wage war, only that it would be “swift, glorious and honourable, worthy of a Triumphal March of centuries past.”

Etrurian War Conference

In early January 1886, Prime Minister Galba met with senior members of the Ministry of War to identify areas where expansion of Etruria’s territory, influence and interests could be achieved. Having replaced most senior figures in the War and Foreign Ministries within months of coming to power, Galba had installed a clique of sycophants and individuals of his political network, most of whom had little to no experience of the positions they held. Gaspare Altomare, the Minister of War proposed expansion into Ajahadya as a means of securing a link between Satria Etruriana and Cyracana, however, this was dismissed by General Metello Frixaturo, who claimed that such a conflict would not be “short, not merciful upon the treasury of the nation.” Frixaturo, a career officer who only held his position due to his personal links to Galba, instead directed attention to be placed on southern Coius and specifically the Bay of Bashurat. In a series of letters to Galba, Frixaturo described the Bay as the “surest defence of our interests both imperial and commercial, from the predations of the Gaullican.”

To back his own position, Frixaturo telegrammed senior officials in Kaoming, Etruria’s treaty port in western Shangea to secure positive analysis of Etrurian expansion there. Elladio Augusto di Darbomida, a Galba ally who was installed as Prefect of Kaoming in 1885, replied with overly optimistic descriptions of Shangea as a “land of endless plenty, both of crop, precious gems, metals, coal and mindless barbarians who would serve any superior, especially those of Solarian heritage.” A second telegram from Captain-General of the Colonial Defence in Kaoming, Giovanni Paolo Iannarelli described the region, “ripe for the institution of Solarian governance, culture and scientific superiority. Soldiers of the Etrurian fatherland, merely need the order and we shall cut through the yellow hordes like a Gladio through the Marolev.” The Etrurian Royal Army’s senior commanders also backed expansion into Shangea when included in the discussions in February. The only source for opposition to the proposal came from the Royal Etrurian Navy, the Ministry of Colonial and Dominion Affairs and select officers of the Army.

In mid-February a major War Conference was hosted by Galba and discussions for a war against Shangea was proposed. The Admiralty immediately rejected the proposal, citing Shangeaese military modernisation and the logistical needs to fight a “colossus of souls.” Leopoldo Arnaldo Vinci, the Minister for Colonial Affairs seconded the Navy’s concerns, he repeatedly referenced Gaullican assistance in the development of the Shangeaese Imperial Army into a modern fighting force. Both the Army and Galba rejected the concerns raised, with Pompeo Fabre, the Captain-General of the Royal Army countering, “then let us use this war to shatter the Gaullican dabbling with the yellow devil.” The more conscious members of the Army who saw the threat of engaging a modernising Shangea took to the proposed war to humiliate Gaullica, by crushing Shangea it would in turn prove their investments worthless.

The Army led by General Fabre sought to persuade the Navy by arguing the geopolitical gains of expanding the Kaoming concession. The Navy in turn was cognizant of the need to guarantee domination of the Bay of Bashurat, but led by Admiral Salvatore Capria still refused to accept a conflict with Shangea would be sufficiently short in conclusion to guarantee success. Ultimately, the Conference voted by majority to prosecute a war against Shangea to expand the Kaoming concession, with the Navy being guaranteed a significant base on the peninsula. The Navy’s hopes of persuading the King to reject the vote failed when Galba produced a letter with the Royal Seal detailing the King’s support for war.

Between February and April, the Admiralty was bombarded by telegrams from the Kaoming administration. With one such document sent by Di Darbomida himself reading, “I urge you to support this enterprise, for all the Army requires is the fortuitous field to crush the yellow barbarian. To do so, we must know that the Navy and its esteemed vessels shall carry the necessary supplies for our enterprise to succeed. Victory will deliver us the Bay of Bashurat, it will deliver us glory and it will confirm you [Capria] as the new Scipio Coianus.”

Shangeaese modernisation

Following the war with the Euclean powers in 1858 reformists in Shangea began to increasingly agitate for the overthrow of the Toki dynasty. Despite attempting to reform both conservative and revolutionary forces frustrated the increasing declining dynasty leading in 1860 to the Restoration War. Concluding in 1864 the war saw Toki Hayato, the last Toki emperor, flee into exile to be replaced by Yao Qinghong who became known as the Xiyong Emperor who declared the Heavenly Shangeaese Empire. The Xiyong Emperor was supported by a mixture of reformist bureaucrats and military officers inspired by the Euclean model of development, traditionalists who resented the reforms attempted by Toki Hayato, nationalists who called for an end to foreign concessions, the Zohist clergy who wanted to return to their premier position in society after a period of decline under the Toki and Sotirians who wished for the new regime to allow them greater liberty in proselytising. The Xiyong Emperor was instinctively a reformist nationalist, but was mindful of conservative opposition and so sought to juggle between the factions.

Shortly into his reign the Xiyong Emperor launched the Great Cultural Rectification Movement (大文化整风运动; dà wénhuà zhěngfēng yùndòng) commonly known as the "Zhengfeng" (Rectification) which aimed to rapidly modernise and industrialise Shangea. The main early component of this was military modernisation - the Xiyong Emperor made sure following his victory over the Toki to abolish the old system of regional militaries and centralise into a single army, the Heavenly Army of Shangea. The successful modernisation of the military over the emperors early rule led to further reforms, such as industrialising Shangea predominantly through foreign investment from Euclean nations and the consolidation of capital into industrial conglomerates, implementing wide-reaching land reform, building railroads, abolishing slavery and institute a "Xiaocisation" policy for minorities. These reforms were increased following the Jiangxu Incident when conservatives attempted to and failed to overthrow the Emperor in a palace coup, although as a result the Emperor became more autocratic in his governing style coming to rely more on Zohist and nationalist elements.

Military modernisation was the most impressive of the Emperor's efforts but had been fraught with difficulties. Under the Toki Shangea had no organised national army - it instead had an elite, all-Senrian force headquartered in Rongzhuo controlled by the central government and a series of armies within the provinces. The provincial armies were the responsibility of provincial governors who could be ordered to mobilise them by the central government in wartime but other then that were administratively separate from central government authority. This led to provincial governors to often act as de facto warlords leading autonomous armies. Under the Xiyong Emperor, the best units from the previous Toki army as well as various provincial armies were merged into a single national army consisting of around 100,000 men. The provincial army system was abolished - the country was instead divided into seven military governates (headquartered in Lukeng, Baiqiao, Caozhou, Shenkong, Kongyu, Rongzhuo and Yinbao) which consisted of several provinces. In the event of a war the national army could order the mobilisation of militias within these governates who would function as a de facto reserve army. Although these militias were less well trained or armed then the national army, they were nevertheless more standardised then the old provincial armies being commanded by professional officers rather then provincial governors. The governate militia's were created to ensure that Shangea could muster its large population in a war whilst maintaining a more central albeit smaller professional core. Conscription was also introduced although its implementation was patchy.

Shangeaese military modernisation however received a big boost when General Sotirien Desjardins arrived on a Gaullican military mission in 1878. The Shangeaese admired the Gaullican army and were keen to copy it, modelling their new system of conscription and military schools on the Gaullican method. General Desjardins was able the spearhead the reorganisation of the command structure into divisions and regiments and overhauled the system of logistics, transportation, and structures to increase mobility. Desjardins's influence also secured Shangea purchasing of the Modèle 74 rifle from Gaullica. By the outbreak of hostilities in 1886 the Shangeaese army was considered to be the most modernised amongst the southern Coian nations of Shangea, Kuthina and Senria albeit still lagging behind its Euclean and Asterian counterparts.

Shangea during this period also embarked on naval modernisation, although this was slower then army modernisation. Shangea had two fleets - for the Hongcha basin and Bay of Bashurat - but only one battleship, the Yuanjin, docked in Baiqiao. Shangeaese admirals favoured the jeune école naval doctrine which emphasised the use of cruisers and torpedo boats to harass and combat larger fleets as well as disrupt trade due to the presence of several, much larger navies in the region.

Military disposition prior to the conflict

Etruria

Since the restoration of democracy in 1810, the Etrurian military underwent both radical technological and organisational changes. The success and resilience of the Etrurian revolutionary armies gave way to new forms of warfare and strategic thinking even under the monarchy. However, over time the nature of politicisation within the armed forces steadily worsened toward the latter half of the century, as the monarchy sought to subordinate the Army to afford protection from a popular revolt. This degradation by politicisation became more apparent in the 1880s, when Galba began to replace key officers with his own personal allies and associates with the King’s support. This denied Etruria’s Army the full potential of its capable and well-respected Royal War Academy in Solaria. The Academy by the 1870s had become nothing more than a vocational boarding school for the Etrurian aristocracy, while the teaching staff were appointed by the King, leading many teachers to be appointed in reward for past favours or loyalty to the crown over talent or competence. While the politicisation of the Army served to degrade its supreme command, it did deliver the Army a steady supply of new technologies and weaponry, as well as a sizeable budget from which it could prosecute the various colonial campaigns in name of Imperial Republicanism. And while the Army was politicised and essentially its highest echelons being turned into a patronage network, the Navy escaped the same fate. As prominent Etrurian historian, Ludovico Gamelli wrote in 1956, “the Restored Monarchy obliterated the prestige and honour the Etrurian soldier earned during the Revolutionary Wars by converting it into a personal club of the King, the Navy however escaped such a fate and instead became the universal focus of the populace – by the time war came with Shangea, the Army was the King’s, and the Navy was the people’.”

The Etruro-Estmerish Wars of the previous two decades also served to compound the significant divergences between the Army and Navy. The wars served to fuel the dichotomy in loyalty of the commands, where the Navy’s much reported victories against the Estmerish Navy further tightened the public’s awe and adoration for the Navy, while the Army’s failures, caused primarily by incompetent leadership and poor planning, tarred its reputation and appeal, forcing the Army to rely upon the King for support and influence. The wars all but guaranteed the Navy’s importance within general Etrurian war planning, as the primary means to supply Etruria’s colonial campaigns and to protect its sea lanes from interdiction. The San Giovanni Marine Academy opened in Povelia in 1867 became one of the most prestigious in Euclea and the Etrurian Royal Navy saw no demand rejected, enabling the country to take a leading role in the development of modern vessels and strategies.

The disposition of Etruria’s armed forces at the outbreak of the war was defined by the country’s fierce rivalry with Gaullica in Coius and in Euclea. As such, a majority of its Army units were stationed either in Etruria proper (owing to the land border with Gaullica) and in Rahelia Etruriana, which bordered Gaullica’s near contiguous colonial possessions in northern and eastern Coius. In the remaining colonies and possessions of Etruria’s overseas dominion, security was dependent upon small regular units and the much larger Etrurian Colonial Auxiliaries (Ausiliari Coloniali Etruriani). The quality of the Ausiliari was dependent upon the colony it served, with Cyracana producing the most praised Ausiliari units of the entire overseas Empire. The Etrurian Royal Army for its part was well-trained, well-disciplined and well-supplied. By 1888, over 90% of Army units were armed with the four-round M1870 Etrurian Vinci variant bolt action rifles, while these rifles fell short of the Gaullican Modèle 74’s range by 50m, the addition of a box magazine on the Vinci rifle, significantly improved its rate of fire compared to the single-shot Gaullican rifle adopted by the Shangeaese Army regulars. The Army was also well-supplied with artillery, including the mass produced Cannone da 149/23. The Etrurian Army also boasted several elite units, including the Esploratori (Pathfinders), who were attached as regiments to each division, the Esploratori were well disciplined in both cavalry and conventional combat.

As of 1886, the Royal Etrurian Army held 150,000 soldiers and could mobilise a further 890,000 reservists from metropolitan Etruria. Of the 150,000, over 90,000 were deployed within Etruria and the remainder were deployed throughout the colonial empire. Much like its fellow continental powers, the Etrurians organised their army into divisions and below that regiments. Each division contained approximately 18,500 troops and 38 artillery pieces when mobilised. The Etrurian Royal Army also operated independent regiments which could be attached or detached to each division at will, these independent regiments usually took the form of either cavalry or Esploratori units. The Army also made provision for “rapid embarkment” (Imbarco Rapido), in which coastal military districts in Etruria would be earmarked for swift deployment overseas, in 1886, only the Solaria Military District and its two Divisions were earmarked and readied for mobilisation and transportation abroad. The biggest issue facing the Etrurian Army besides its compromised officer corps, was the lack of sizeable merchant ships to transport both men and supplies from Etruria to Western Shangea. The Royal Etrurian Auxiliary Fleet, which would nominally be tasked with supplying any war effort was regularly forced into servicing private commercial interests and with the war in 1886, only a third of its fleet was free to supply the Army in Coius. Etruria’s industrial capacity, while weaker than the other great powers, was sufficient to supply forces at home, though the ongoing urban tensions would dog Etrurian arsenals and weapons factories throughout the war, denying a steady supply of materiel.

The Royal Etrurian Navy at the time of the war, was one of the largest and most advanced of the great powers. Since the Etruro-Estmerish Wars of the 1860s and 1870s, the Navy had become the premier branch of the two and as a result, enjoyed a steady supply of ships and funds to innovate. The Etrurians built and launched the first ever ironclad in the First Etruro-Estmerish War (1863-1865) and would maintain its development of iron-clad vessels. By 1886, the Etrurian Navy was the second largest in the world and had built some of the most advanced turreted warships of the day. Unlike the Army, the Navy escaped the politicised degradation of its command and academies, with the San Giovanni Marine Academy in Povelia being globally renowned. The Etrurian Navy’s culture and training traditions placed great emphasis on crew discipline and cohesion. The Etrurian Navy also trained its crews and officers to prioritise accuracy over rate of fire and to engage at range, where its heavier vessels held advantage.

Unlike Shangea which adopted Jeune École, the Etrurian Navy placed greater emphasis on command of the sea, based on the theory of Neptunian Thought (Pensiero Nettuniano), and saw the destruction of the enemy fleet in a single decisive battle as key to achieving victory, as such, the Etrurian Navy was primed to specifically locate and engage the Shangeaese Navy, this would enable the Navy to then blockade and interdict key points; ports, coaling stations and geographical chokepoints.

At the outbreak of the war, the Etrurians had deployed their Navy in accordance to its concerns over Gaullican aggression at home. As such, the Far-Seas Fleet of the Navy was earmarked for deployment against Shangea. The Far-Seas Fleet included three turret ironclads (2 Aurelio Pompeo-class, one Benedetto di Valle-class). And was escorted by an assortment of six protected cruisers, as well as torpedo cruisers and smaller gunboats. The Far-Seas Fleet was placed under the command of Admiral Caio Romolo di Impera, a career officer who saw successes against Estmere the decade prior. The Far-Seas Fleet was supported by several major ports in Satria Etruriana, despite Gaullica prohibiting Etrurian ships coaling in ports it controlled in Western Coius.

Shangea

Since beginning military modernisation in the 1860's Shangea had undergone a revolution in military terms. The adoption of Euclean drill, tactics and organisation was implemented in the 1870's under a military mission led by Sotirien Desjardins and his deputy Guillaime de Learé who implemented a widescale reorganisation of the Shangeaese army in almost every respect introducing a system of divisions and regiments to boost mobility, placing more focus on the army's transportation and logistical system and establishing artillery and engineering regiments under independent commands. Desjardins also emphasised the connections of Shangea's seven major military bases by railway but with the Shangeaese rail system being underdeveloped in the 1880's this idea was still in its infancy in 1886.

By the start of the war in 1886 de Learé estimated that the Shangeaese army counted some 163,500 men organised into sixteen divisions each consisting roughly 10,200 men split two infantry brigades of two infantry regiments of three infantry battalions (7,200), an artillery regiment of twenty-four guns (180), a cavalry regiment of ten squadrons (2,000), an engineer battalion of four companies (400) and a transport battalion of four companies (400). However there was wide differences between the quality of each division with some better trained in army drill then others. The 42,000 strong Third Army was widely considered to be the best trained and equipped army in Shangea and amongst south Coian nations as a whole, with de Learé describing it "as worthy for combat as any Euclean army - perhaps not of Gaullican or Weranian stock, but certainly sufficient to beat a bestial Soravian or slovenly Estmerish".

However, whilst the regular army had undergone intense modernisation the same could not be said for the regional militia's that underpinned Shangeaese military policy. These militia's were poorly equipped and trained, being at best a gendarmerie force. Whilst the regular army was almost entirely armed with some form of rifle it was estimated that up to 60% of all militia members were not armed with rifles or muskets, instead wielding a variety of variety of swords, spears, pikes, halberds, and bows and arrows. As de Learé wrote in his report to the Gaullican Army at the outbreak of war; "of the militias, I have nothing to say other then they are what is expected of Coians. They are a dreadfully armed rabble whose existence serves to only drain supplies and equipment from the rather impressive regulars".

The Shangeaese military's greatest weakness was its equipment and logistical problems. The regular army suffered some problems garnering a consistent stream of equipment, although by the 1880's these problems had begun to dissipate as Shangea moved increasingly to producing its own variants of the Modèle 74 rifle and its own artillery, the Jianxing gun. By 1886 a member of the Gaullican military mission lieutenant Marcel Saint-Yves noted that "the greatest deficit the regulars find themselves in is uniforms - which is amongst the fairest of problems to confront". Saint-Yves noted however that the underdeveloped rail network "severely limits the mobility of the Shangeaese army" and like de Learé concurred that the militia's were "at best, an unneeded indulgence and at worst actively malicious to the ability of Shangea to prosecute a war".

Nevertheless, the Gaullicans were more-or-less impressed with the Shangeaese military leadership whom de Learé called "on the whole excellent staff planners and seemingly aware of the great difficulties their military faced". Shangeaese military strategy was largely determined by Zhang Haodong, the key military adviser to the Xiyong Emperor. Zhang's overall strategy in the event of a Euclean invasion was to raise the militia's to force the Euclean army into fighting a war of attrition, during which Shangea would mobilise its regular army and deliver a coup de grâce through a series of decisive victories.

Key to this strategy was the acceptance of use of human wave attacks and high casualty rates amongst militia troops. Zhang admitted that his strategy would incur large losses of life for Shangeaese forces but reasoned that as militia forces were usually badly led, had poor morale and often paid late by provincial governments that they would be unreliable and so their commanders had to use simple tactics that emphasised a maximum concentration of force to work within his grand strategy. Zhang's plans were considered generally to apply to the west of the country where railway networks were most developed and where an Euclean attack was most expected - the investment of railways and detailed mobilisation plans in the Kaoming peninsula were credited as key to Shangeaese success during the later war.

The Shangeaese navy had less investment then the army but was considered to be more generally modernised. The navy was also modelled after its Gaullican counterpart, although Shangea failed to secure a generous naval training programme as it had done the army from Gaullica. The Shangeaese navy was split into two fleets - the Hongcha and Bashurat Fleets - with the Bashurat Fleet based in Lunkeng led by Xiang Liuxian. General Shangeaese naval strategy was based on the jeune école doctrine with Shangeaese naval planners not hoping to be able to defeat Euclean battles in a conventional naval battle but rather to disrupt them long enough to deny them the ability to resupply colonial armies, thereby enabling the Shangeaese army to defeat land forces and force a peace treaty on the enemy via a victory by fait accompli.

Naval strategy however was hampered by the fact that most naval tactical books were written in Gaullican, which only a fraction of senior naval officers were familiar with. Training manuals had begun to be translated in 1884 under the command of Admiral Xiang (who spoke fluent Gaullican) but this process was only partially implemented by the time war broke out in 1886. The majority of ships in the navy had been purchased from Werania and Gaullica before the war - according to one estimate, half of the entire Shangeaese navy had been brought from Gaullica over 1877-1886 and assembled in Shangea.

The Shangeaese navy was less confident then the army of victory when war was declared, with Admiral Xiang reportedly bursting into tears when he heard the news. Prior to the Etrurian declaration of war the majority of the Hongcha fleet - including the flagship Yuanjin - was transferred to the Bashurat fleet out of the fear of the Etrurian navy, whilst the government confiscated many civilian vessels to use as auxiliaries.

Most military observers believed at the start of the conflict that Etrurian forces would prevail. The Weranian general Friedrich von Hönigberg commented that "whilst some Shangeaese forces can be said to imitate Eucleans, they are no match for the real thing. Mark my words, this will be a victory for the Etrurians reminiscent of the Solarian Empire". The Gaullican military mission in Shangea was one of the few to disagree with this analysis with Desjardins writing to the then-governor of Jindao "as long as the regulars are deployed properly and promptly, the Shangeaese are in a clear and enviable position to decisively defeat Etrurian forces through sound leadership and sufficient military organisation."

Border Crisis

Etrurian mistreatment of railway workers' on the Kaoming-Wangzhuang railway had led to widespread discontent in the Kaoming peninsula which coupled with a shaky government presence in the region and rampant regional corruption led to the creation of several bandit groups and militias which roamed the countryside. One of these were the so-called Imperial Banners' Army, a group numbering no more then 1,000 that nevertheless began to engage in anti-concessionist terrorism disrupting the rail line and periodically killing Etrurian citizens if they ventured into the countryside.

Although the group was relatively marginal their persistent violent actions towards Etrurians provided a convenient casus belli for Etrurian colonial officials eager to expand their influence into Shangea, crush anti-concessionist forces and possibly annex even greater portions of the Kaoming peninsula. After members of the Imperial Banners killed an Etrurian missionary Gianpiero Audia outside the neutral zone on the 17th September 1886 the Etrurian governor of Kaoming General Elladio Augusto di Darbomida claimed that Shangea had "ignored all civilised rules of conduct". Di Darbomida claimed that the killing of Audia reflected a consistent violation of the neutral zone by the Shangean government with the Kaoming administration conflating the Imperial Banners with government forces. Di Darbomida subsequently called for the neutral zone to be directly annexed into the Kaoming administration and for Etruria to be given substantial interests within the Kaoming peninsula to transform it into a de facto protectorate.

The Shangean resident-general in Kaoming Long Xinya did not believe that Etrurian was planning to use military force to enforce its demands and recommended to the central government to offer a compromise of ceding the current neutral zone and expanding a new one, but ruling out the creation of a protectorate over the peninsula as a whole. On the 4th October Long sent a telegram to the Etrurian consul in Gaoming offering to cede the neutral zone, but recieved no reply. The Shangean government had publicly condemned efforts to cede the neutral zone but had been slow to react to the crisis, focusing on the harvest season despite vigorous protests from general Desjardins.

The contradictory stance of the Shangean government and their comparative military passivity made the Etrurian government and the colonial office more receptive to militarily enforcing their demands over Shangea. With the Etrurian War Conference earlier in the year having decided to prosecute war against Shangea, a casus belli arranged and Shangea dithering in the face of diplomatic pressure the Etrurian government approved of the imminent commencement of hostilities.

Although Etruria had planned to go to war with Shangea for several months it had not communicated this information to other Euclean nations. The ultimatum to create a protectorate over Kaoming came as a surprise to Euclean capitals who did not affirm support for the Etrurian expedition.