Borland (Kylaris)

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Republic of Borland Republick op Borland Republik Borland Republik âb Boorland | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Borland (dark green) within the Euclean Community (light green) |

| Capital and largest city | Newstead |

| Official languages | Borish Borish sign language |

| Recognised national languages | Estmerish Weranian |

| Recognised regional languages | Azmaran Aldman |

| Demonym(s) | Borish, Bor[note 1] |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Anton Godsman | |

| Anita Hoven | |

| Legislature | Parlament |

| Establishment | |

• First mention | 9th century |

• Formation of Heathland League | 1050 |

• Unification into Kingdom of Borland finalized | 1356 |

• Personal Union with Estmere | 1801–1808 |

| 22 March 1936 | |

• Independence | 1 January 1938 |

| Area | |

• | 68,239 km2 (26,347 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 1.45 |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 12,325,000 |

• Density | 178.01/km2 (461.0/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | estimate |

• Total | $498.300 billion |

• Per capita | 40430 |

| GDP (nominal) | estimate |

• Total | $511.488 billion |

• Per capita | 41500 |

| Gini (2020) | low |

| HDI (2020) | very high |

| Currency | Euclo (EUC) |

| Time zone | Euclean Standard Time |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +43 |

| ISO 3166 code | BO |

| Internet TLD | .bo |

Borland (/ˈbɔːrlænd/; Borish: [ˈbɔːɾland]), officially the Republic of Borland (Borish: Republick op Borland; Weranian: Republik Borland), is a country in northeastern Euclea. It is bordered by Estmere to the southwest and west, by Werania to the north, by Azmara to the northeast and by the Gulf of Assonaire to the southeast. The capital city of Borland is Newstead.

Borland has a population of 12.3 million people and is heavily urbanised, with a large portion of the population being concentrated in the Midlands, the Lowlands and in Outhallside. The largest city in Borland is Newstead, other major cities including Westhaven, Olham, Outhall, Lewen and Stunhill. The economy of Borland can generally be described as a mixed social market economy which has largely transitioned from being industry-based to being service-based over the last decades. Living standards are generally high and there is a robust welfare state with universal healthcare and various forms of social security. Borland is a member state and founding member of the Euclean Community. The country is in the Community of Nations, the ECDTO, GIFA, AEDC, the ICD, the ITO as well as the Estmerish Community and the Northern Forum.

History

Prehistory

Antiquity

Middle Ages

The Marauder Age is believed to have started around the beginning of the 9th century, starting to decline through the 10th century before ending in the 11th century. Raids are documented in most parts along the shoreline of modern-day Borland, with the primary targets being the towns of Dunhelm, Newdune and the city of Westhaven, which eventually saw the formation of Marauder kingdoms. As raids mostly targeted coastal regions, with few raids in the interior of the country, it is generally believed that the Marauder Age saw the first split of Borish culture and politics into coastal and inland areas.

The mid-10th century saw the formation of the first yends, initially as highly decentralized states. This, however, changed with the Estmerish invasion of Borland in 1047 under Richard I of Estmere, who sought to bring Borland under Estmerish rule. The invasion failed, with Richard I being killed in battle in 1049 and most of Borland remaining outside of Estmerish control by 1050. Furthermore, a loose alliance that had formed between most of the yends during the war had become the Confederation of Borland shortly after the end of the war.

The Confederation of Borland initially was a pluricentric state, with each yend acting as a sovereign state for most purposes. Main centres of political and economic activity were the cities, often referred to as steads, of Olham, Lewen and Outhall, with numerous steads of secondary importance. The Confederation suffered from a great degree of internal competition, seeing the territorial expansion of steads into the surrounding countryside as well as conflicts between the steads, in an attempt to increase the influence of a given stead. This ultimately culminated in the outbreak Borish Unification Wars in 1342, in which Yorn of Outhall sought to unify Borland by force. In response to the incorporation of Maynes into Outhallside in 1343 and the siege of Yulleigh in 1344–1345, the remaining Midlands — at the time consisting of several yends — unified to fight against Outhallside. Though there were initial successes, such as the reconquest of Yulleigh in 1347, by 1350, Outhall had managed to conquer several major steads, including Yulleigh, Lewen and Manham. By 1353, the interior of Borland had mostly unified into the Kingdom of Borland, with Yorn of Outhall being crowned the first King of Borland. His successors sought to expand Borish rule into Hethland along the coast and Waderham in the north, with limited success.

• personal union with Estmere (formalized 1801–1808)

• Great War (de facto autononomy with fall of Estmere (temporary), and independence 1938 (after 1936 referendum))

• decentralization (of government), secularization (of the state), liberalization (of society), modernization (of the economy)

• move from traditional parties (conservatives, nationalists, democratic socialists) to “new” parties (ÞC, GPB, þnS)

Geography

Borland is located in Eastern Euclea on the coast of the Gulf of Assonaire, spanning from the coastal plains of Hethland in the east via the plains and hills of the centreregions to the hills, valleys and mountains of the northwestern regions of Finstria and Burgh. The country is bordered by Estmere, Werania and Azmara.

Major rivers include the River Aire, which flows from Finstria through Norland and the Midlands to the south of Newstead and to the Lowlands, where it flows into the Gulf of Assonaire at Westhaven, the River Leith, which flows through Maynes–Yord and the Midlands before joining the River Aire just south of Newstead in Brigge, the River Haer which divides Hethland into what was historically North Hethland (Azmaran) and Hethland proper (Borland), before flowing into the Gulf of Assonaire at Newdune, and, the rivers Linn and Wader, which flow through Burgh. Furthermore, parts of the River Leeth together with the River Dover (which splits into the Upper Dover through Maancester and the Lower Dover through Yord as one goes upstream) form around half of the Azmaro-Borish border, while the River Leeth forms part of the border with Estmere.

Borland lacks lakes of significant size, although there are several hundred smaller lakes, most notably in Maynes–Yord (whence the Borish name for Maynes: Manneghlaak). In Finstria and Burgh, especially in the formerly separate yend of Bergland, there are many smaller dams and resevoirs, the largest one being close to the stead of Werlew.

Climate

The climate of Borland is typical for northeastern Euclea.

Environment

Politics and Government

Political Parties

Political parties in Borland include the Workerʼs Party of Borland, the Conservative Party of Borland and Centrum.

Administrative Divisions

Prior to the administrative reform of 1970, Borland was divided into three regions, which were divided into a total of fourteen yends, which were further subdivided into municipalities (cryes (counties) and steads (cities)). With the 1970 reform, the regions alongside the regional branches were, for the most part, abolished. Furthermore, several yends were combined, bringing the total number of yends down from fourteen to seven.

Military

Borland has a comparatively small military, officially referred to as “Army of the Republic of Borland” (Borish: Armië þer Republick op Borland/Armië op þe Republick op Borland, Weranian: Armee der Republik Borland) or simply “Army of Borland”. After independence, it was created to ensure the sovereignty of Borland, though the country started demilitarizing during the 1940s. Since the beginning, the Borish military has been a professional army, with conscription never having been implemented and having been specifically ruled out in 1984. Currently, it stands at around 2,500 active servicemen, though that includes not only soldiers, but also doctors and nurses, amongst others. They are most known for their work as national guard, border control and, formerly, as riot police.

Foreign Relations

Economy

Energy

Industry

Infrastructure

Transport

Demographics

| Rank | Yend | Pop. | Rank | Yend | Pop. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Newstead | Midlands | 1 510 000 | 11 | Norstead | Borish Lowlands | 223 000 | ||

| 2 | Westhaven | Borish Lowlands | 537 000 | 12 | Minster | Midlands | 187 000 | ||

| 3 | Olham | Midlands | 365 000 | 13 | Werlaigh | Finstria | 180 000 | ||

| 4 | Outhall | Outhallside | 345 000 | 14 | Yerham | Borish Lowlands | 176 000 | ||

| 5 | Stunhill | Norland | 339 000 | 15 | Manham | Midlands | 175 000 | ||

| 6 | Millham-Ladbatch | Borish Lowlands | 295 000 | 16 | Dyrham | Borish Lowlands | 167 000 | ||

| 7 | Lewen | Midlands | 256 000 | 17 | Lester | Borish Lowlands | 165 000 | ||

| 8 | Bringham | Borish Lowlands | 251 000 | 18 | Johnslare | Outhallside | 156 000 | ||

| 9 | Endham | Borish Lowlands | 234 000 | 19 | Heartham | Midlands | 154 000 | ||

| 10 | Bermon-Legham | Midlands | 224 000 | 20 | Millham-on-Leith | Midlands | 153 000 | ||

Borland is inhabited by 12.3 million people.

Demographically, several splits between different population groups can be observed within Borland. The most significant of these include the ethnolinguistic split of Borland (into Estmerish, Borish and Weranian/Aldman) and a split on religious boundaries. Historically, this was within Sotirianity into and within the Amendist and Catholic churches. Major Amendist churches include the Church of Borland (sometimes referred to as “Kerk” or “Kerke”, from its Borish name: kerke op Borland), the Free Amendist Church of Borland and the Embrian Communion in Borland, while major Catholic churches include the Solarian Catholic Church in Borland and the Free Catholic Church of Borland. Besides these, there are several dozen splinter churches of varying size, influence and theological position.

Languages

According to census data, the most widely spoken native language in Borland is Borish, with ca. 4.847 million native speakers, which amounts to ca. 68.03% of the population. Furthermore, at least 2 million people claimed enough knowledge of Borish to hold a conversation in it, meaning at least 6.85 million people (c. 96.14%) of the population of Borland. Various studies identify many varieties of Borish vernacular Estmerish as closer to standard Borish than to standard or even dialectal Estmerish, meaning that the number of Borish speakers might be actually higher.

The traditional heartland of the Borish language consisted of Outhallside, Maynes, the Midlands and Hethland, the former of which maintaining the language even during Estmerish domination. Borish has spread into historically Azmaran-speaking areas, such as Yord and North Hethland over the past centuries, with early stages of an expansion into historically Estmerish- and Aldman-speaking areas being observable in census data, especially in Norland and parts of Burgh.

The standard variety of Borish is based on written Middle Borish as well as the spoken dialects of Outhall and Newstead. The main dialects of Borish are those of the Midlands, Outhallside, Maynes (incl. parts of inland Hethland), Yord and (coastal) Hethland. Besides these, there are also distinct dialects forming in the traditionally Estmerish-speaking areas, such as Westhaven or Norland.

The second most widely spoken language in Borland is Estmerish, spoken natively by about 1.456 million people (c. 20.44%), although this figure includes both Estmerish and Swathish, which is commonly dismissed as a dialect of Estmerish. During the 19th and into the 20th century, Estmerish was rapidly replacing spoken Borish, which was often also seen as little more than a particularly diverging dialect. Upon Independence, Estmerish was the majority language in the yends of Norland, Lowlands and Midlands (excluding Newstead), while being the plurality language in Newstead and South Hethland, although it has since regressed to being the majority language only in Norland, the Lowlands as well as some parts of the Midlands and South Hethland.

Traditional Estmerish dialects in Borland form a continuum from Norland to Westhaven, with the most distinctive dialects being those of urban Stunhill and the Westhaven metropolitan area.

Borish Estmerish differs from the Estmerish of Estmere, somewhat more in its spoken than in its written form. For instance, the second person singular pronoun “thou” (alongside the verbal conjugation -(e)st) has been retained in Borish Estmerish, with many speakers outside of Westhaven having a characteristic rhotic dialect in which the rhotic is an alveolar tap ([ɾ] in all positions. The latter of these is often the case in spoken standard Borish Estmerish as well, with written standard Borish Estmerish differing from written Estmerish Estmerish in a handful of spelling conventions (e.g. parlament, governement or fassade instead of parliament, government, façade/facade).

Similarly to Estmerish and Swathish, Weranian and Aldman are also combined, the two languages being spoken natively by 1.365 million (c. 19.16%) people in Borland. For most of history, the main language of North Borland was Aldman, although it was mostly replaced as a written and spoken standard by Weranian, with significant dialect levelling having happened since the mid-20th.

Roughly 124,000 people in Borland (c. 1.74%) speak Azmaran natively, primarily around Yord and in North Hethland. Furthermore, Savader is spoken by 56,000 people in Borland (c. 0.79%), while only around 30,000 people claimed to be Savader in the same census.

Five languages have an officially recognized status in Borland: Borish, Estmerish, Weranian, Aldman and Azmaran. Of these, Borish is recognized as the official language on a national level, although it, Weranian and Estmerish and recognized as national languages. Furthermore, Aldman and Azmaran have a recognized status as regional languages. More recently, there have been calls to also give the Savader language official recognition.

All Borish people have the constitutional right to communicate with the government in their native language, including the right to an interpretor if their native language cannot otherwise have services provided in it.

Most Borish are proficient in at least two of the four national languages, many also being proficient in at least one foreign language. 90% of Borish claimed to be fluent in Estmerish, rising to 96% in provinces other than Finstria-Burgh, with 85% being fluent in and a further 96% saying they have at least conversational knowledge of Borish. With the national languages (Estmerish, Borish, Weranian, Aldman and Azmaran), most speakers speak local dialects of a given language rather than the standard form in their everyday life, with the proficiency in the standard form of the language varying across the country, but moreso across social classes.

The most common foreign languages other than Estmerish to be studied in Borland are Gaullican and Weranian. On average, Borish students rank among the highest in terms of Estmerish-language proficiency.

Religion

Prior to Sotirianization, a Weranic paganism was practiced in what is now Borland. As archæological finds are scarce and hard to interpret, and written language was not introduced to the area on a large scale until well after Sotirianity became dominant, the information on this faith in Borland is limited. Despite Sotirianization, some earlier traditions are still found, for example in the dates of specific Sotirian holidays or in the Estmerish and Borish names for days of the week.

As in Azmara, Estmere and parts of Werania, the Reformation and Amendist Wars saw the split of the church in Borland, with a majority becoming Amendist although a sizable Solarian Catholic minority remained. Since the beginning, Amendism in Borland was split into two: the Church of Borland (Borish: kerke op Borland) and the Free Church of Borland (Borish: freë kerke op Borland), the primary difference being in the Free Church maintaining the identity of Catholicism, although severed from Solarian Catholicism, even going as far as to officially refer to itself as the Sotirian Catholic Church of Borland (Borish: sotirianish-catholishe kerke op Borland). With the growing Estmerish domination in politics and culture, the Embrian Communion was introduced to Borland.

The Constitution of Borland guarantees freedom of and from religion and prohibits discrimmination on the basis of religious identity. It also maintains that the state is separate from religion. Especially during the early decades of independend Borland, secularism was often interpreted as the state not interfering in religion and the internal matters of religious groups at all. This policy together with leniency displayed by authorities as a whole after legislation was strictened allowed for religious splinter groups to gain momentum, with several dozen local and regional so-called “free churches” of varying size, influence and theological stances forming. According to census data, 7.5% of all Borish residents are members of one of the free churches, commonly referred to as “freechurchers”.

There are small communities of other religions, primarily of Atudites (64,125) and Irfanis (71,962), at 0.9% and 1.0% of the total population, respectively. A large portion of the Atudite community in Borland is found in Newstead, Lewen and Westhaven, with significant smaller communities in Outhall and Yulleigh. The Irfani community of Borland is based in and around Westhaven and consists largely of recent immigrants.

Studies consistently show that there is a large number of Borish people who identify as belonging to a religious group while being irreligious — between 35% and 43% of Borish are believed to be irreligious, although only 23.5% identified themselves as such on the last census. The role of religion in building identity is thought to be a main contributor to this, as even people who do not or no longer believe might still identify as belonging to a given religion and its community.

Education

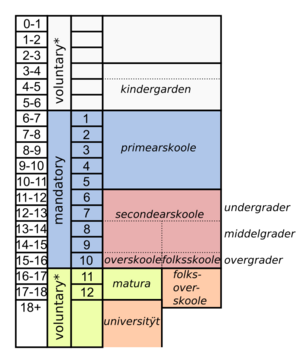

Education in Borland is universally accessible and mandatory between the ages of six and sixteen (or years 1 to 10). The country has a high literacy rate, with 98.4% of adults being literate in at least one of the countryʼs national languages. The school system is divided into primary schools (years 1 to 5) and secondary schools (years 6 to 10), with tertiary education being divided between universities and trade schools. Most parts of the Borish education system are public, including all primary education, most secondary education and a majority of tertiary education. The education system is heavily standardised and centralised, particularly in regards to secondary education, where a single nation-wide curriculum for all schools exists. All schools in Borland use the same grading system with 00 as the lowest and 15 as the highest grade. Typically, 05/15 is the passing grade.

Public kindergartens (Borish: kindergarden, plural: kindergerden) are available for children between the ages of three and six, with a space in a public kindergarten being a right for children once they turn four since 2005. Although there have been several motions throughout the years to establish public daycare facilities for children below the age of three, these have largely been unsuccessful. However, around two thirds of private kindergartens have spaces for children below the age of three as of 2023. Since 2006, a pre-school program (Borish: forskoole) is being rolled out at all public kindergartens, intending to prepare children for primary school. There is an ongoing debate about making pre-school attendance mandatory for all children.

Primary schools (Borish: primarskoole) are the first level of the mandatory education system in Borland. They consist of years 1 to 5 and feature a standardised core curriculum (“reading, writing, counting”) alongside some degree of liberty for teachers and schools, particularly in subjects outside the core curriculum. The standard age of school entry is six, although some children start primary school at age five or seven instead, most commonly due to turning six within weeks of the beginning of the school year or as to not to separate friends or siblings.

Secondary schools (Borish: secondarskoole) are broadly divided into two types: general schools (Borish: folksskoole) and matural schools (Borish: maturalskoole). While general schools consist only of years 6 to 10, matural schools also have a matural level (years 11 and 12). Excluding some minor differences in the year 10 curriculum as well as the ability to get a matura, matural schools and general schools do not differ by much. Secondary schools are internally divided by years, with years 6 and 7 being referred to as “undergrades” (Borish: undergrader), years 8 and 9 being referred to as “middlegrades” (Borish: middelgrader) and year 10 (as well as 11 and 12 if applicable) being referred to as “overgrades” (Borish: overgrader). At the end of year 10, all students go through a general centralised exam (Borish: generalet centralexam, GCE), consisting of a series of tests in several subjects. The minimum grade required to pass in a GCE test is 05/15 and students are allowed to fail a GCE subject and still get a GCE certificate. Passing in the GCE is required to be able to enroll in the matural level, with some employers also requiring a GCE certificate of their workers.

Matura is a qualification granted after passing exams at the end of a two-year period known as the matural level (consisting of years 11 and 12). Students select five subjects to count into their matura known as matural courses, but have to attend other classes as well. As in the GCE exam, a grade of 05/15 or better is required to pass, with failing in one matural exam automatically disqualifying a student from getting a matura unless the student passes upon retaking the exam. After the matura exams, students in year 12 no longer attend school, but have to wait until every exam is graded, with the matura certificate being handed out at the end of the school year before summer holidays. The matura is a necessary qualification for university as well as for some professions.

Most universities in Borland are public and can be accessed free of charge after successfully graduating with a matura, although some subjects require a minimum grade. Until recently, students with a worse matura than required by a subject were still allowed into any university course after waiting for several semesters, although this is being phased out gradually. While other forms of education count in years, universities count in semesters. All subjects have a standard number of semesters, though a large portion of students take longer. Borland is home to nine public universities, the largest of which is the University of Newestead. Additionally, there are numerous private universities, many of which charge tuition.

Trade schools (Borish: tradenskoole) are typically attended after receiving a GCE certificate, although it is often not a necessary requirement to attend. In addition, many students have attempted or even passed matura or have been to university before going to a trade school. During usually two or more years, students are taught a profession, which usually includes exams at the end of each semester as well as internships. Other forms of education most prominently include paid internships and apprenticeships (grouped together as “paid education”), often in private companies. For some professions, these are an alternative to trade schools, for others, these are the only methods of getting into a specific profession.

Health

Borland has a universal healthcare system that covers most medical and certain cosmetic procedures free of charge to all Borish residents, regardless of citizenship. Most hospitals, including university hospitals, are owned jointly by the state and the respective municipality. Smaller medical clinics are, however, owned privately with subsidised services and usually with a specialisation (e.g. in dentistry, women’s health or children’s health). Similarly, most services in the relatively few private hospitals are subsidised fully or in-part as part of the national health program or private insurances.

The national health program (NHP, Borish: rykssundhÿdsprogram, RSP) belongs to the Ministry of Health and was established in 1937 as part of the post-war reconstruction and improvement efforts within the field of healthcare. It is a form of universal health insurance that was initially supposed to be phased out in favour of private insurance, although this policy was reverted by the Borish government in the 1970s and 1980s. Everyone who pays taxes in Borland pays into the national healthcare fund from which the NHP draws most of its funding. In addition to this, about 65% of Borish pay for a private health insurance, which offer some services not included in the NHP, as well as certain privileges, such as greater comfort or getting prioritised in non-emergency situations in private clinics — which is illegal in public ones.

In most areas of medicine, Borland performs average for North-Eastern Euclea. The life expectancy in Borland is 75.5 years for men and 82.2 years for women (a difference of 6.7 years), averaging at 78.85 years. Birth rates are, for North Euclean standards, relatively high, with a fertility rate of 1.85, though this varies greatly regionally.

Culture

Literature

Music

Art

Cinema

Fashion

Traditional Fashion

Media

Cuisine

Sports

Holidays

Borland recognizes eleven public holidays, with several further holidays which are commonly observed not being official. Of the eleven official holidays, six are so-called “silent holidays” (Borish: stille healeghdaghe). The Government of Borland does not usually vote on or pass legislation, with public life in general being more limited on these days (including all Sundays). Borish law treats Sundays and regular holidays similarly, with the silent holidays being regarded as more serious or otherwise in special need of protection from potential disturbances.

Both within general Borish society and in the application of anti-disturbance laws by authorities, there has been a clear trend towards a more relaxed view on holidays. Sundays and regular holidays historically saw very strict bans on most retail activity, a ban on public alcohol consumption and dancing as well as a ban on any noisy or otherwise offensive activities, with silent holidays having seen almost no retail activity and a stricter code on what is socially (and legally) acceptable behaviour in public. Over the decades, this has relaxed to allow for almost all retailers to be open on Sundays and regular holidays (although mandating closing hours in the early afternoon and a higher minimum wage), with other bans nowadays being limited to what is not allowed on weekdays either — for example loudly listening to music or shouting in public or in private to a degree that it is inconsiderate of neighbours or other members of the public. On silent holidays, the ban on activities such as singing, dancing, grilling or generally working in public is still largely in-place, with a previous ban on having parties in specially rented establishments being lifted only in 2014 after having been only scarcely enforced since decades. The legal restrictions on silent holidays are subject to much debate, especially outside of religious and conservative circles, where they are often deemed as encroaching on individual freedoms to an excessive degree. Another commonly raised concern is that the abundance of Sotirian holidays among silent holidays sees the state not maintaining the separation of state and religion to the extent that it had commited to within its Constitution. A common form of protesting the silent holidays which can especially be seen in larger cities is pairs or small groups of people dancing silently in parks, on plazas and in other public spaces.

| date | Estmerish name | Borish name | Weranian name | holiday? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 January | New Year’s Day | newenyaarsdagh | Neujahrstag | |

| variable | Good Friday | forfrÿdagh karenfrÿdagh |

Karfreitag | |

| variable | Pascha Sunday | paschasondagh | Paschasonntag | |

| variable | Pascha Monday | paschamondagh | Paschamontag | |

| 22 March | Referendum Day formerly: Union Day |

referendumsdagh eanhÿdsdagh |

Referendumstag Einheitstag |

|

| 1 May | Labour Day | werkersdagh | Arbeitertag | |

| 20 May | Mother’s Day | maþersdagh | Muttertag | |

| 23 June | Father’s Day | faþersdagh | Vatertag | |

| variable | Harvestfest | harvestsdagh | Erntedankfest | |

| 31 October | Rememberance Day Peace Day |

allerdoaden mimerhÿdsdagh frieþensdagh |

Allertoten Volkstrauertag Friedenstag |

|

| 1 November | All Soul’s Day | allersealen | Allerseelen | |

| 24 December | Nativity’s Eve | healighavend nativitÿtsavend/nativitÿt |

Heiligabend/Weihnachten | |

| 25 December | Nativity’s Day | ferster nativitÿtsdagh | erster Weihnachtstag | |

| 26 December | Second Nativity’s Day | twÿder nativitÿtsdagh | zweiter Weihnachtstag | |

| 31 December | New Year’s Eve | newenyaarsavend | Neujahrsabend |

Of these holidays, Good Friday, Pascha Sunday, Pascha Monday, Rememberance Day/Peace Day, All Souls’ Day and the First Day of Nativity are the six silent holidays that are officially recognized in Borland. In addition, Nativity’s Eve is a silent holiday after 14:00 or 15:00 in some regions, while being so after 18:00 nationally. For a substantial portion of workers, these as well as January 1st, May 1st and December 26th are also work-free days.

The Sotirian holidays around Pascha (pascha [ˈpɑs.xɐ] or pasha [ˈpɑʃɐ] in Borish) are observed on the same dates as in neighbouring countries and, generally speaking, follow very similar traditions.

The 22nd of March has been a holiday in Borland since several centuries, with its meaning and associated traditions changing drastically over time. When and where it was first celebrated is unknown, although it is widely believed that it started among the Borish aristocracy in the mid-12th century with feasts to celebrate the creation of the Kingdom of Borland via the unification of the various Borish states, although it might have been the date of a holiday even prior. Throughout the time of the Personal Union with Estmere, it had shifted in its meaning of “unity” from the unity of Borland and its people as a distinct cultural identity to one of the union of Borland and Estmere. With the 1936 Borland independence referendum being held on the 22th of March 1936 and its outcome being narrowly in favour of independence, it was reinterpreted again as a day to celebrate the distinct cultural identity of Borland. In 1937, 22–23 March saw a wave of violence by Estmerish and Borish nationalists alike, something that would repeat every single year since.

Labour Day historically saw parades to honour workers, although this has taken a side role next to the traditional 1st of May marches, protests aimed at raising awareness of current issues, especially sociopolitical in nature. Being a general work-free day, but no silent holiday, in early spring, it has become tradition for many Borish families to start the grilling season on this day, or to otherwise spend time together by promenading, hiking etc., making the holiday having changed its meaning from a celebration of the worker to a day for the appreciation of what one has outside of work, although the former theme still is present.

Although already celebrated since around a century, neither Mother’s Day nor Father’s Day are not officially recognized. Of note is that both holidays had traditionally been observed on a variety of dates, with many families deviating from the date listed here to this day. Children in school and kindergarten often make small gifts, such as decoration, drawings or calligraphic art, for their parents on the respective days. As small gifts, especially chocolate and flowers, are commonly gifted by children and among spouses, these holidays have become somewhat important in retail in a similar manner to Valentine’s Day, although this one is not generally regarded as a real holiday. Similar holidays whose celebration is less common within Borish society include International Children’s Day and International Women’s Day. Within Borland, there have been calls to elevate all four of these to the status of officially recognized holidays in recent years.

Rememberance Day or Peace Day has been celebrated in Borland since the end of the Great War, with the date right before All Souls’ Day having been picked specifically to allow for one day dedicated to the victims of war, violence and recently deceased as well as one day dedicated to all those who died. Being silent holidays, especially Rememberance Day is controversial as, since its beginning, it has been observed as a day to celebrate the end of the War and peace in general by some, rather than a day of mourning as is officially sanctioned. Many families visit graves of deceased family members and friends on November 1st.

In recent decades, the emergence of Halloween in Borland, celebrated on the same date as Rememberance Day, has seen controversies and criticism. Halloween traditions that can be found in other countries, such as trick-or-treating and publically wearing costumes, are highly unusualy in Borland, as the threat of fines for violation of silent holiday legislation and overall public outcry have prevented it from becoming popular in Borland to a degree that can be compared to neighbouring countries.

In contrast to many other countries, Nativity’s Eve takes the role of both Nativity’s Eve and Nativity itself for pretty much all purposes. Though there always were distinct traditions to the celebration of Nativity in Borland, there has been a larger shift since the Great War and Independence. While historically, there was a Mass held in the late evening of Nativity’s Eve and another one in the morning of Nativity, with children receiving their gifts on December 25th, the Evening Mass has been pushed into the afternoon in most churches — others offering two Evening Masses. This possibly has its roots in curfews of the War and post-War era not allowing for late Mass, but has resulted in other family traditions being pulled forward to the late evening of Nativity’s Eve, such as an after-church family dinner followed by giftopening in the night of the 24th. As a result of this cultural shift, Nativity’s Eve has started to be referred to as just “Nativity”, followed by the two “Days of Nativity” — Boxing Day being an increasingly rare regional equivalent to the Borish second day of Nativity.

Until 1985, New Year’s Eve was a public holiday, while New Year’s Day was not. In response to a statistically significant increase in traffic accidents due to commuters not having fully sobered-up from New Year’s festivities, the a report by the Ministry of Infrastructure suggested switching the holiday status and declare January 1st a generally work-free day, which was the case since 1986. In addition, at several points in recent Borish history, a partial ban for non-essential travel with private cars has been suggested, although such legislation has yet to pass the Parlament.

Since 1946, the use of fireworks outside New Year’s night without a dedicated permit has been banned, though such permits were issued regularly, including for private use. Since 1973, the availability of fireworks and similar pyrotechnics has been limited to the time between the day after the Second Day of Nativity and New Year’s Eve, while the criteria for permits to be issued has been tightened. Furthermore, in most instances, only specially certified pyrotechnics are legal since 1993, with heavy fines for the import or use of illegal fireworks. More recently, a complete ban of private fireworks has been suggested for environmental and safety reasons, as the noise from fireworks frightens wildlife, creates heavy pollution and poses a significant safety hazard.

Notes

- ↑ While “Borish” may refer both to someone who identifies as ethnically Borish as well as to someone with Borish citizenship or residency, “Bor” only refers to the former.