Marauder Age

Template:KylarisRecognitionArticle

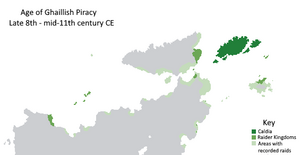

The Marauder Age (8th century-11th century CE) was a period during the Middle Ages when Ghailles known as Marauders carried out wide-spread raiding and conquest throughout Euclea. It followed an expansion of the Ghaillish population which required additional resources. In the Caldish Isles, these resources were at times limited. The Ghailles of this period are often referred to as Marauders as well as Lochlananch, though the latter is only commonly used in Caldia.

Ghaillish pirates conducted raids throughout Euclea, with Caldish galleys being recorded of having reached as far west as Soravia and as far south as Tsabara. Raids were most common in the North Sea region of Euclea. Ghaillish settlement primarily occurred in Borland, Estmere, Geatland, Soravia, Scovern, and Werania. The longest-lasting Marauder kingdoms were Connland in eastern Scovern and Nevsland on the northern coast of Geatland. The expansion of Ghaillish peoples followed Caldish unification in 720. Some Caldish historians argue that the actual First North Sea Empire was established by the Ghailles during the Marauder Age. This is disputed by other historians, however, on the grounds that the Ghaillish pirates were not consistently actors of the Ghaillish crown and their raids and conquests were not consistently an extension of the monarch’s de jure or de facto authority

Conquest and raids were driven by a several factors. Overpopulation and a lack of arable land contributed to Ghaillish piracy. The unification of Caldia also resulted in political strife, centralizing power in a way that it had not previously been. This motivated some Ghaillish warriors to look to other lands for political independence from the Ghaillish crown. Wealth in Euclean towns and monasteries and the weak rule of overseas kings was also a factor. The historical use of the long fada by the Ghailles and new developments in sailing also drove expansion.

Most information about the Marauders is drawn from primary sources written by Eucleans who interacted with the Ghailles during this period. Archaeology and some secondary sources, including Ghaillish folklore, also contributes to the understanding of the Marauder Age.

Historical background

Caldish Marauders were mostly warriors who lived in the coastal regions of Caldia. Initially, they were outside of the direct influence of the newly established Caldish monarchy. Many of them were Sotirians, but some Marauders were pagans or still practiced pagan beliefs. Marauders primarily settled in Borland, Estmere, Geatland, Scovern, and Werania. There was also some Ghaillish settlement in Azmara, Caithia, Soravia, and Kirenia.

Old Ghaillish was spoken by the Marauders and the language was spread through settlement of northern Euclea. The process of Sotirianization of the Ghailles began in 711. The spread of Sotirianity and its association with the Caldish monarchy cause unease among the native pagan population. A tax was levied on non-Sotirians in late 791. It resutled in a high number of conversations to Sotirianity. Historians also believe it was a motivating factor for non-Sotirian Marauders to settle outside of the Caldish Isles.

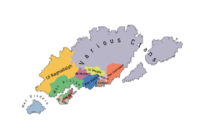

The tribes of Caldia had been unified by 720 under the central authority of the Kingdom of the Ghailles. Caldish unification had wide-reaching political ramifications for the Ghaillish clans. Prior to unification, the clans were largely independent of one another. This period is known in Caldia as the túatha. Túath is an Old Ghaillish term used for kingdom, meaning a geographical area and the people who lived there. Historians have identified over 30 small kingdoms that had existed in Caldia before 720. These kingdoms were effectively tribal confederacies.

As an island, the sea had always been the only way of communication and trade between the Ghaillies and the outside world. Ghaillish people had long been noted for their use of the Ghaillish longship, or longa fada, by Eucleans. Advancements in shipbuilding practices resulted in the construction of warships that could reach farther distances. These ships were initially sent on raiding expeditions. Overtime, Ghaillish sailors acted as traders, explorers, and colonizers as well as pirates.

In the immediate years before the first Marauder raids began, Caldia experienced a period of religious upheaval and political instability. A tax on non-Sotirians was levied by the crown in 791, which in turn guaranteed their freedom from persecution.

Probable causes of Ghaillish raiding

There is a debate among academics as to what motivated the Ghailles to begin raiding and expanding their territory starting in the eighth century. There are several popular theories with widespread scholarly backing. Overpopulation, political changes, a lack of resources, and customary practices are the four main motivations actively debated by scholars.

- Cultural theory: This theory suggests that the Ghaillies were motivated by their culture and traditions. Seafaring in the Caldish Isles dates back thousands of years. Tenic peoples arrived in Caldia after sailing from the Euclean mainland. Historical sources also make note of Ghaillish seafaring customs. Borealia, a written source from 96 CE, describes the Ghailles, known to the Solarians as the Caledones, as sailors. They are also noted for the use of the Ghaillish longship. All means of historical communication and interaction with the outside world had to be done by sea. Seafaring was also a major theme in Caldish mythology. This theory argues that improvements in sailing technology was the natural continuation of Ghaillish seafaring. The Sotirianization of the Caldish Isles is also used to support this theory.

- Demographic theory: The demographic theory argues that Ghailles migrated from the Caldish Isles as a result of a growing population and a lack of arable land to sustain that population. Despite the tumultuous process of Caldish unification, the years that followed were peaceful. With a central political authority established, disputes between clans were mediated and violent conflict was prevented. This resulted in the expansion of the islands' population. The agricultural of the islands did not increase. This resulted in food shortages and left many without property and status. Piracy grew as a result, giving wealth and prominence to those without land or status. Raiding was carried out in order to bring food and other resources back to the Caldish Isles. As the population continued to grow, the Ghailles migrated to politically weak areas in northern Euclea and eventually beyond.

- Economic theory: Supporters of the economic theory believe that Ghailles were motivated by the wealth of other kingdoms during the Middle Ages. Having long traded with the medieval realms of Euclea, Ghailles sailors were familiar with their wealth. Other Euclean regions were significantly wealthier than the Caldish Isles. A lack of resources and wealth is believed to have motivated Ghaillish sailors to turn to piracy, which became more profitable than trade. Political instability and weakness in some of Euclea's medieval kingdoms created openings for Ghaillish pirates, who toppled native kings and replaced them with Ghaillish rulers.

- Political theory: The political theory suggests that the Ghailles turned to piracy for political reasons. Caldish unification resulted in the first central political authority over the Ghaillish people. Prior to unification, Caldia was home to over 30 identifiable kingdoms. Many of these were tribal in nature. The subjugation of the Caldish Isles under the Kingdom of the Ghailles resulted in a new political strife. Some chieftains were displeased with this new authority. As such, they were motivated re-assert their authority. Sotirianization resulted in continued political strife. Failed revolts caused dissatisfied chieftains to look elsewhere, resulting in Ghaillsh expansion.

- Religious theory: This theory argues that Marauders were motivated by the changes brought about by the Sotirianization of the Ghailles. The process began in the early eighth century but intensified following the unification of the islands under a Sotirian queen. Non-Sotirians were oppressed during the late eighth century. In 791, non-Sotirians were ordered to pay a tax to the Ghaillish crown. This tax protected them from persecution and allowed them to practice freely. It resulted in a large number of conversions. Some historians argue that the tax resulted in migration, as non-Sotirians did not want to pay to practice their religion freely.

Historical overview

Northeastern Euclea

The first recorded Marauder raids took place between 790 and 800 along the costs of northeastern Euclea. Raids were carried out during the summer months, as the Ghailles would spend their winters in Caldia.

The first raids targeted the islands of Svoyen, Geatland, and Caithia. The earliest recorded Marauder raid targeted the Scovernois burgh of Orlafen in 792. The proximity of these island chains to Caldia and the lack of unified states made them frequent targets for early Marauder raids.

Caithia was frequently raided by the Marauders and was conquered in 801. It was ruled independently of the Kingdom of the Ghailles.

Marauders would settle the eastern coast of Scovern in 839. The city of Connheim was established by Conn of Knockdale. Ghailles migrated to this region, which came to be known as Connland. It became a base of operations for Marauder activity in Scovern and modern day Werania. Some Marauder leads were active in the fragmented politics of Scovern. Connland was later conquered by the Scovernois during the 12th century.

Land along the northern coastline of Geatland was settled by the Marauders. Gorm the Elder attempted to undermine Ghaillish influence in Geatland and started the Städ War. Marauders backed Gorm's rival Harald Halstensson but were ultimately defeated. Land under Marauder control was gradually reduced until the 11th century. Despite this, Marauders continued to pose an active threat to Geatland and had at times had notable influence in Geatish politics.

Werania was regularly raided by Marauders. Settlements were set up along the northern coastal and some regions were fully brought under Marauder control. Marauder activity in Werania peaked during the 10th century. Weranian lords gradually reduced the influence of the Marauders, despite inaction from the Rudolphine Confederation.

The Marauders raided the coastline of Azmara. In 872, the city of Nordberg was conquered by Oíngus of Nordberg. It became a major hub for trade among the Marauders. Control of the city was lost in 992. Azmara experienced Marauder raids until the 11th century.

Borland was targeted for coastal raids starting in the early 9th century. Many coastal settlements were raided and destroyed by Marauders. Dunhelm, Newdune, and Westhaven were frequent targets for raids and were eventually established as Marauder kingdoms. While the coastal regions of Borland were frequently targeted for raids, the interior saw little Marauder activity.

Estmerish cities were frequently raided by Marauders. Modern day Estmere was home to several Weranic petty kingdoms, some of which were weak. Marauders were drawn to Estmere by the number of unprotected monasteries and its expansive coastline. The historical capital of Tolbury was sacked by the Marauders first in 859 and again in 872. Marauder activity generally occurred closer to the coast. A group of raiders under Seárlas White-Eye established the fort-city of Dún Lonrach in 911, on the site of modern-day Dunwich, and it quickly grew into a sizable kingdom in its own right. From Dún Lonrach, the Marauders could strike as far south as central Gaullica. The Kingdom of Dún Lonrach remained a major Marauder state until the Verique conquest of Estmere in the 11th century.

Southeastern Euclea

Raids were recorded by Catholic monks in Gaullica, Auratia, and Etruria at varying points between the 9th and 10th centuries. Marauder activity in southeastern Euclea was last recorded in 1012 when raiders landed and sacked the Etrurian city of Accadia for the final time.

In 856, an account from Gaullican monks reported a Marauder fleet sacking the city of Maredoux. A report several days later from a courtier in Côte Serene suggests that same fleet sacked the city before raiding smaller settlements throughout the Assonaire region. Oral accounts from residents in Verlois claim to have seen the fleet pass by their city, which was spared from attack. It is speculated that Cormac of Narin led the raids. He was an active Marauder in the Gulf of Assionaire and is recorded to have led a series of raids in southern Estmere the year before. Raids in Gaullica continued, but the Verliquoians were able to deal a number of defeats to Marauders. A number of Marauder bands were hired as mercenaries in the service of the Verliquoian Emperor Philippe II, later forming the emperor's personal guard for a time. Some Ghailles settled in Gaullica as a result of their service, with Diarmuid of Lavardin rising to prominence by being awarded lands.

Coastal and river cities in Auratia were raided. In 917, Marauders sacked and conquered Hascara, holding the city of 17 days before abandoning it. Fabria was sacked and much of the city was destroyed by Abbán Mac Ailbe in 932, leaving the city in ruin for over a decade. Smaller raids were recorded throughout Auratia at different stages into the 10th century.

Marauders successfully launched raids on the cities of Accadia, Porto di Sotirio, Povelia, and Tyrrenhus. Accadia was sacked successfully several times and was a frequent target for Mauraders in the 9th and 10th centuries. A permeant base was set up at the mouth of the Fiastra river after 872. This allowed Maruaders to strike throughout the Solarian Sea. The fractured nature of the Etrurian city states and petty kingdoms created an opening for Marauders to target the wealthy region. An attempted raid on Solaria was defeated by the Povelian, Girolamo Oberdan in 876. However, the base was destroyed and Marauders expelled in 891. Raids continued throughout the 10th century.

Central and western Euclea

Early marauder raids rarely reached as far as western Euclea, but as marauders spread over eastern Euclea as Ghaillish proficiency with the long fada increased, raids in the west became larger and more frequent. Coastal settlements in present-day Kirenia were first targeted for raids sometime during the 9th century. Woodcuts from Kantemosha in the 9th century detail marauder raids on its eastern cities, and the first recorded raid in Soravia by Ghaillish marauders was in 870. The relatively recent Marolevic migration and population of the area left many of its biggest cities and trade hubs vulnerable to proficient and experienced marauder raiders. Many of its largest cities, including Samistopol, Ovdapol, Lipa and later Luchintsy were raided and sacked by marauders over the course of the 10th century. Only with the rise of the Duchy of Pavatria as a unified force in the region did the marauder raids partially subside.

In 949, Eleanora of Caldia established the Kingdom of Maltaire as a marauder kingdom on Soravia's northwestern coast. Her, and much of the Uí Mealla clan, relocated from Caldia to capitalise on the newfound wealth that a unified Pavatria brought. Widespread piracy occurred across the Pavatrian coast, with trade ships being intercepted and cities sacked and looted. These raids peaked in the 950s, where Maltaire reached the peak of its power. Raids on fortress cities in Kantemosha and Ambrazka also intensified around this time. Eleanora fell ill and died in 970, and was succeeded by her son Flaithbertach Uí Mealla, who oversaw the kingdom's decline and eventual invasion and subjugation in 976 by Moimir the Kneebringer. The marauders that were not killed in the invasion ended up relocating elsewhere in northern Euclea. Marauder raids mostly stopped after the invasion of Maltaire.

Coius

Marauders have been recorded as sailing as far south as Tsabara. Despite recorded voyages in Rahelia, there is no evidence to indicate that Marauders targeted Rahelian settlements for raids. An archaeological search found Ghaillish coins and other Marauder artifacts in the Trifaoui Province on Tsabara's northern coastline. The excavation found evidence that supports a small Marauder settlement having been established here, likely during the 10th century.

Some written sources and records indicate that bands of Marauders did sell some Eucleans as slaves to the Rahelians. The Marauder Caolán is recorded as having sold 35 Eucleans into slavery in 945. Evidence does not indicate that the practice was widespread, as most Marauder activity was in northern Euclea.

Marauders are also believed to have sailed to Bahia, though this is largely unsupported by available evidence.

The Asterias

Historians have struggled to find concrete evidence to support stories that Marauders reached the Asterias between the eighth and 11th centuries. Ghaillish folklore and secondary sources dating back to the Middle Ages speak of several bands of Marauders who sailed across the Vehemens Ocean and found a new land. The most famous of these stories is the legend of Saint Brendan of Caldia. Folklore suggests he lead a group of Marauders to a land in the far east, which could be Asteria Superior. Saint Brendan is said to have settled in the land he discovered, establishing successful monasteries. One account of his story suggests he was preaching to a group of "Far Easterners", possibly Native Asterians[a]. However, there is no conclusive evidence to suggest Ghaillish pirates reached the Asterias during this period. There have been no archaeological findings in Asteria Superior that show Ghaillish activity either.

Decline and end

Marauder activity gradually began to decline during the late 10th century. The efforts of Euclean kings and nobles to counter Marauder raids became increasingly successful. The domestic situation in Caldia also began to shift. The largely decentralized authority of the Caldish monarchs provided Marauders with the opportunity to conduct ample raids. However, the ascension of Ailbe II in the late 980s saw great political change. The Kingdom of the Ghailles was reformed into the feudal Kingdom of Caldia. This political reorganization granted the Caldish monarchs new authority. As such, the activities of the Marauders were hindered as the monarchs sought to curtail the power of rivals. Many Marauder leaders had considerable influence, making them threats to the authority of the crown. A number of prominent Marauders participated in a revolt against the Caldish crown in 1021. Ailbe had several powerful Marauder leaders exiled from Caldia and some were put to death as a result of their participation. This significantly weakened the Marauders who continued to operate out of Caldia.

Ailbe II's successors were able to maintain the power she established. The authority of the Caldish crown became increasingly centralized as additional reforms were implemented. Advances in trade between Caldia and Euclea proved more profitable than raiding. The crown benefited directly, as taxes implemented on trade generated significant income. The general shift towards mercantilism in Caldia also resulted in the expansion of the merchant class. Merchants became influential and were opposed to Marauder activity. Marauder raids negatively impacted trade. At the request of some of Spálgleann's most influential merchants, Fiona I had large groups of Marauders arrested. Marauder outposts in Caldia were also destroyed on her order. This effectively brought an end to Marauder raids originating from Caldia.

Outside of Caldia, many of the Marauder kingdoms and cities were gradually reconquered. Marauders had lost all of their holdings on the Euclean mainland by the middle of the 11th century were expelled from Geatland in the late 11th century. Fiona's move against the Marauders in Caldia prevented them from reinforcing the Marauder kingdoms in Euclea. Fiona had little interest in propping up these states, as the Caldish crown had no authority over their lands. Her successors continued this policy. The formal end of Marauder influence is considered to be the reconquest of Connland by the Scovernois in the early 12th century.

Legacy

During the late Middle Ages, the legacy of the Marauders was contentious. Marauders were largely remembered throughout Euclea for their violent conquests and raids. Accounts of Marauder history were largely oral. There is some evidence of written communications from the period discussing the brutality of the Marauders. According to Elmo, a monk who lived during the 11th century, Pope Guy VIII often spoke of the brutality and barbarity of the Marauders. The frequency of raids southeast Euclea and the failed Marauder attempt to conquer Solaria is believed to have created a negative perception of Marauders and by extension the Ghailles. This contributed to an already strained relationship between the papacy and the Catholic Church in Caldia, which was known for its independence, heresy, and anti-popes. Similar perceptions of the Marauders existed in northern Euclea, which had the most recorded Marauder activity. One exception were the Verliquoians. Marauders were recruited as mercenaries by the Verliquian emperors and some formed the personal guard of Philippe II. While written accounts indicate that the Marauders were still known for their brutality, the Verliquoians respected them as warriors and sought to make use of their skills. The Marauders also had a lasting legacy in Soravia that continued for most of the Middle Ages. However by 1650, that legacy had been largely eroded. Louis II led a cultural eradication campaign to rid the area that used to be Maltaire of Ghaillish-derived names. Most he towns and cities in the area were renamed and personal names of Ghaillish origin were likewise purged.

Much of the history of the Marauders was based on the sagas associated with them. These written sources were translated into Gaullica and spread throughout Euclea. They were largely viewed as reliable sources until recently. Today, few scholars accept them as reputable sources. The sagas, which as considered to be fictionalized and semi-legendary accounts, shaped the legacy of the Marauders in the post-Middle Ages period. While the brutal nature of the Marauders was featured, it mostly focused on legendary or semi-legendary heroes and stories of their valor. The Marauder sagas resulted in an association of bravery, greatness, and even chivalry. The most prominent saga was A generali historia latronibus insidiaretur (A general history of marauders) by the 16th century Caldish historian and cartographer Áedammair Mac Laisrén. Mac Laisrén is accredited with recreating the image of the Marauders from one of brutal conquerors to one of valiant warriors. His work reflected a general attitude in Caldia that was favorable to the Marauders that first appeared at the start of the 12th century.

The Marauders were heavily romanticized by Caldish romantics. This built on the reputation of the Marauder as the valiant warrior. Marauders were portrayed in Caldish romantic art and literature during the 19th century. Modern historians, who base their understanding of the Marauders on archaeology and numismatics, largely dispute the depiction of Marauders in the post-Middle Age sagas and Caldish romanticism. The general consensus among historians is mixed, associating the culture of bravery with one of violent conquest.

Notes

- ↑ Mentioned in the writings of the Caldish monk Tadhgan of Rosmuc.