Duran

Kingdom of Duran | |

|---|---|

| Motto: འབངས་བདེ་སྐྱིད་ཉི་མ་ཤར་བར་ཤོག་།། Bang deki nyima shâwâsho May the Sun of Peace and Happiness shine over all people | |

| Anthem: བསྟན་འགྲོའི་ནོར་འཛིན་རྒྱ་ཆེར་སྐྱོང་བའི་མགོན། Tendroe Nordzin Gyache Kyongwae Gön | |

| Seal Royal Seal  | |

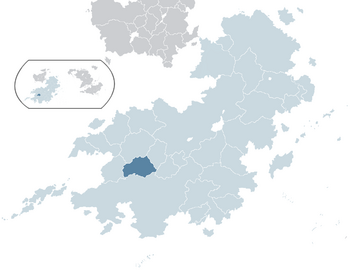

Location of Duran in Coius | |

| Capital and largest city | Chenpodrang |

| Official languages | Namka |

| Recognised national languages | Tromka |

| Recognised regional languages | Hua |

| Ethnic groups (2020) | Dzakto 51% Hill people 28% Nampa 16% Shangeans 6% |

| Demonym(s) | Duranian |

| Government | Federal parliamentary semi-constitutional monarchy |

• Zhabrung | Namgyal Gyemtsen |

• Pönchen | Tsering Gyatso |

• Nam Desi | Bijendra Nayak |

| Legislature | Kashag |

| Assembly of Elders | |

| Assembly of Commoners | |

| Area | |

• Total | 681,891.84 km2 (263,279.91 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 0.380 |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 28,424,000 |

• Density | 168/km2 (435.1/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2016 estimate |

• Total | $ 454.64 billion |

• Per capita | $ 15,995 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | $179.49 billion |

• Per capita | $6,315 |

| HDI (2020) | 0.708 high |

| Currency | Duranian gormo (DUG) |

| Internet TLD | .du |

The Kingdom of Duran (Namka: ནམྱུལགྱལཁཔ Namyul Gyal Khap, Tromka: आकाशीय राज् Ākāśīya Rājya), commonly known as Duran, is a sovereign state in Coius. It shares land borders with Ajahadya to the north, Shangea to the south, and Baekjeong to the east. It is entirely landlocked. As of 2017, Duran's population was approximately 28 million. Its capital city is Chenpodrang, which is also the largest city in the country.

Continuous habitation within the area of modern Duran began in the neolithic era, with the Matu culture being the first emergence of what is commonly considered to be a proto-Hua ethnic group in the Lhochum valley in approximately 3000 BCE. The first of the Duranic groups arrived in the sixteenth century BCE, during the Shango-Duranic migration. The Duranic peoples would come to occupy the fertile river valleys, establishing incipient valley states which pushed the Hua into upland regions of Kussuria. As these valley states convalesced into the Namrong Dynasty, peoples fleeing the expansion of the Xiang Dynasty to the south led to the Gyadrul period. Namrong itself would become a client of the Xiang until 900 AD, when it broke free of a weaker central state. A dynastic transition led to the rise of the Great Nam, a major power which at its beak stretched across much of Satria. The wholesale importation of prisoners of war under the Great Nam to man rice paddies permanently changed the demographics of the region, creating a highly cosmopolitain urban populace. Though the Great Nam would fall by the late 1300s, rump states persisted for the next 500 years as client states of neighbouring powers. It was not until the 19th century that the modern Duranian state emerged, with the unification of several Nampa and Tromka-speaking principalities under the Namgyal dynasty. This state, while independent, remained withdrawn and conservative, rejecting modern economic developments as anathema to local values. This led to its economic backwardness, and by 1882, king Dorji Namgyal was entirely dependent on Shangean support. As Shangean imperial ambitions grew, he was deposed in a palace coup by a group of powerful Shangean merchants in favour of his daughter Lhamo, who had been educated in Shangea and was married to a Shangean. Dorji fled to Ajahadya, where he unsuccessfully petitioned the Raj for military help, before fleeing to Euclea in exile. Meanwhile, Lhamo was swiftly deposed and Duran annexed by Shangea which began a campaign of Shangeanification and modernisation of Duranese society. During the great war, the exiled Dorji’s lobbying of several great powers was enough to have Duran granted independence in the Treaty of Keisi.

Since independence, Duran has been weakened by tensions within its society. Though much of the traditional elite had welcomed the return of Dorji, the Dzakto commoners opposed a return to reactionary despotism and hill tribes, who had been targeted during Shangea’s modernisation campaigns, were in a state of revolt. Duran suffered at the hands of violent socialist and regionalist insurgencies, which led to a change to constitutional monarchy and the institution of the Dratsung system which granted autonomy to many rural hill tribes. Despite this, Duran remains a deeply stratified state in which the Nampa minority hold a highly privileged position both economically and socially. Though caste was officially abolished, it remains a factor in terms of access to education and resources especially in rural areas, while many critics accuse the government of using the Dratsung system as an excuse to ignore development in hill tribe-majority areas. Democracy in Duran is limited by strict lèse-majesté laws which prohibit outward republicanism, while vote rigging is seen to be common. Duran is a close strategic partner of Senria and Ansan, forming a key part of the cordon sanitaire envisaged around Shangea. However, Duran's developing economy is closely linked to its southern neighbour and the small Shangean minority remain highly important to the nation's economy. The current Zhabrung is Namgyal Gyemtsen, while the bicameral heads of government are Pönchen Tsering Gyatso and Nam Desi Bijendra Nayak.

Etymology

The name Duran is an exonym of uncertain origins. One potential etymology has been derived from the Parbhan word द्वार dvāra, meaning door or gate, in reference to the nation's position guarding the main land entrance to Shangea from Satria. This would then have passed through Old Pardarian, becoming دواران Dvārān or "land of the door", entering into Euclean languages. Another etymology is from the Pardarian word دورا dûra, meaning "far away". The official name of Duran is Namyul (ནམྱུལ Namyul), literally meaning "land of the sky", or more symbolically "Heavenly Realm". Duran and its derivatives are only used in correspondance in other languages. In Shangean, Duran has historically been referred to as Namu (纳姆 Nàmǔ) and Beishan (北山 Běishān).

History

Prehistory

Settled by modern humans during the peopling of Coius, Duran's location as a key pass between modern day Satria and Shangea meant it was a key route during the spread of mankind. Archeological digs in the country's lowlands have revealed stone tools and other hallmarks of human habitation dating back at least to 4,000 BCE. The earliest known sedentary state-based civilisation was the Matu culture, which spanned the late neolithic and early chalcolithic periods. Centred upon the Miatsua valley, the Matu culture is held to have been an ancestor of the modern day Hua people and with its riverine location and condensed urbanisation is held as a proto-Valley state. The demise of the Matu culture appears to have occured around 2700, when a sequence of natural disasters appear to have led to mass depopulation. Other Hua tribal entities took up sedentary living, but were not able to achieve the same degree of prominence as the Matu. Though the Hua were the first major cultural group to inhabit the fertile valleys of Duran, they would be displaced soon after by the migration of Durano-Chanwan peoples originating in Shangea. This major migration pushed the Hua from most of the prime agricultural lands, resulting in the ethnogenesis of the agrarian Nampa people. The Nampa had more stratified social structures, building towns centred on wet rice agriculture and trade.

Namrong Kingdom

Xiang Dynasty

Namkha state emergence

Coup and Xiaodongese suzerainty

Post-Great War period

The period which followed the Treaty of Keisi was one of significant unrest in Duran. Dorji's return to power was accompanied by a purging of collaborationist officials and nobles, and many Shangean merchants and traders were disposessed of their assets. Violent rioting erupted in the capital city, as Shangean businesses were targetted by mobs of nationalists who claimed vengeance for the occupation. The north of the country, dominated by Hua hill tribes, was in a state of anarchy and controlled largely by autonomist militias who had resisted Shangeanisation. While much of the population welcomed the return of Dorji and de facto independence, elements of Duranian society had grown disillusioned with the monarchy in general and staged protests against its return. Inspired by the Green Pardals in Satria, a group of radicals under the leadership of Ugyen Lhundrub founded the Duranian Popular Republican Movement. This group promised a socialist government which would bring democracy and an end to the inequalities which were omnipresent in the country. This group was initially peaceful, holding major sit-ins in public places across the country and spreading its message to the countryside where living conditions were especially poor. Two months after assuming governance, Dorji passed away and his eldest son Kalsang Jigme Namgyal ascended to power. Seeing opportunity, the socialists held major rallies hoping to prompt his abdication. Instead, the Royal Guard were instructed to fire upon the crowd, killing 50 and injuring countless others.

Now disillusioned with peaceful action, the DPRM began to advocate a people's war in order to gain power. Armed cadres lauched attacks on police and army installations, as well as establishing rural areas which they controlled. The new Zhabrung found himself in a difficult position, with large swathes of his country in the hands of rebels, and was forced to look abroad for aid. In 1938, troops entered the country from INSERT and helped to reassert the royal government's control of major urban centers. This intervention also served to dissuade Shangean involvement. In rural areas the conflict continued unabated, with both the Royal Duranian Armed Forces and Duranian Popular Republican Movement being accused of brutal massacres. The conflict in the north of the country was especially bloody, presenting a three-way clash between the Chenpodrang government, DPRM insurgents, and local militias, which varied from self-defence militias to those which advocated for Hua national self-determination. In 1951, the DPRM initiated the Cagmo Offensive, a major military campaign which aimed to take control of the country through simultaneous attacks on major settlements, strikes, and protests. Once again, the government was forced to lean upon foreign support to maintain power, with several cities coming under socialist control. However, aided by INSERT forces, the king was able to reassert control and the DPRM's gains had been lost.

Part of the success of the Cagmo offensive was the apathy of a large portion of the urban population towards the rebels, who had not resisted against the guerillas. The Cagmo offensive's successes had convinced the royal government that some form of political reform would be needed, and in October 1951 Zhabrung Kalsang Jigme Namgyal announced reforms to the government's structure. Duran's government had consisted of the Zhabrung and Kashag, a consultative assembly composed of Nampa aristocrats, with no constitutional controls over the monarch's power or democratic representation. Under Kalsang's constitution, the Kashag was reformed into a bicameral legislature composed of the Assembly of Elders, unelected nobles and clergy, and the Assembly of Commoners which was elected directly. The position of Nam Desi was also created, similar to the position of Premier in other nations. Political parties were legalised, though under the condition that they could not be involved in republicanism or possess an armed wing. This announcement weakened the DPRM, as many of the movement's more moderate members broke away to form the Duranian Socialist Democratic Party. The first elections were held in 1952, and despite violence by the DPRM were considered successful. Kalsang now turned his attention to the situation in the Hua-majority regions, signing the Vuantoo accords with several major militia leaders. The Vuantoo accords allocated several seats in the Assembly of Elders to Hua customary chiefs, and guaranteed voting rights to Hua. It also established the Dratsung system, which permitted autonomous governance in Hua areas to protect their traditional cultures and ways of life. While this did not completely solve the issue of hill tribe insurgency and the area remained rife with banditry and small arms possession, the threat to the central government was low.

With the immediate pressures of the hill tribe insurgency alleviated, the Duranian government was able to turn its focus wholely to the socialist threat. Their strategy took two major forms; a concerted military effort to clear out known "liberated zones" which provided the movement with income, and a social campaign aimed to weaken the movement's appeal among the peasantry. Weaponising the rural population's religiousity, the Duranian government took steps to associate the regime with the clergy and build up local welfare networks. Several monasteries established agricultural co-operatives, which concentrated political authority in religious institutions which were close to the regime while providing support for the peasantry. This directly threatened to cut off the socialists from their major support base, and they responded by attacking several monasteries in an attempt to dissuade peasants from joining the co-operatives. The government was able to use these attacks against the socialists, who had until this point expressed neutrality upon the clergy, and the socialists lost popularity. By 1962, the DPRM were a shadow of their former selves and controlled scant territories near the border with Ajahadya. In 1964, following divisions within the party, the groups deputy leader Passang Geymutsang defected and gave away the locations of several safehouses. Ugyen Lhundrub was captured by security forces, and following a short trial was executed. Though the DPRM pledged revenge, they were no longer able to pose a genuine threat to the government and instead turned to terrorism.

The mid sixties up until the late seventies were a period of considerable stability within Duran. The wars in neighbouring Satria made the country, which had by now emerged from its own civil strife, seem an attractive location for investment. Under Zhabrung Kalsang Jigme Namgyal, the nation attempted to market itself as an international economy especially within the domain of tourism. Though there was still tension with Shangea, economic cooperation between the two countries gently warmed. On the domestic front, increasing economic prosperity prompted a growth of urbanisation, growing populations, and light reforms to improve the democratic situation in the country. The rise to power of Sun Yuting through a military coup in 1970 in Shangea began to cast a shadow over this era of prosperity, while on the domestic front the decision to build the Kartrinpa Dam, itself a result of the rising urbanisation, led to the emergence of the Ro Salvation Socialist Front and a recommencement of insurgency among the hill tribes. These two factors were worsened by Ajahadya's dramatic defeat in the Third Satrian War. Refugees fleeing the violence streamed into the country, causing a demographic challege as the country struggled with economic downturn and returned instability.

- Border tensions with Shangea to be sorted

- Modern situation

Geography

Climate

Environment

Politics and Government

The 1951 constitution, which is generally regarded as having cemented the modern Duranian state, establishes Duran as a constitutional monarchy, albeit one in which the Zhabrung exerts significant power and authority. The Zhabrung has been the head of state of Duran since the emergence of the nation around the 17th century, though the Namgyal dynasty which currently occupies the position only took the position in 1821. Until 1951, Duran was an absolute monarchy in which the Zhabrung wielded all political authority and the Kashag, which in the modern day is a legislative wing, was a mere consultative body composed of other hereditary nobles. Though the constitution of 1951 limited the Zhabrung's power, the position is still the ultimate source of authority in the nation. It is charged with representing the nation internationally, is the nominal head of the Royal Duranian Armed Forces, grants the final approval on any bills passed within the Kashag including the ability to veto legislation, and is permitted to dissolve the Kashag and trigger a vote of no confidence for political figures. The Zhabrung is also protected by strict lèse-majesté laws which prohibit speech or actions deemed offensive to the monarch or monarchy, which effectively prohibits explicit republicanism, and an object of religious veneration for a portion of the population due to his purported lineage tracing back to a Cakela. The current Zhabrung is Gyemtsen Namgyal.

The Kashag, the national legislative body of Duran, is a bicameral assembly composed of the Assembly of Elders, an assembly of 60 nominally appointed members, and the Assembly of Commoners which comprises 200 elected members. The Kashag is a historical institution in Duran which dates back to the earliest establishment of the modern Duranian state, though similar bodies are attested in earlier Nampa polities. Until 1951, the Kashag consisted purely of hereditary aristocrats from the Dzongs and Chenpodrang-based royal court and was a purely advisory and consultative body. The new consitution reformed this by adding a lower house, the Assembly of Commoners, which would be directly elected by the populace, and granted the Kashag legislative powers. Further reforms came with the Vauntoo accords, which granted several hill tribes representation within the Assembly of Elders and recognised their customary headmen. These two houses function according to the principles of perfect bicameralism, in that a bill must be approved by both houses before it can be passed into law. Each of the two houses also elects a head, the Pönchen and Nam Desi respectively. The Pönchen is typically the most senior religious figure in the Assembly of Elders, while the Nam Desi will usually represent the head of the largest party in the Assembly of Commoners. These two positions are theoretically equal, sharing the responsibilities typically assigned to a head of government.

Military

Foreign Relations

Economy

Energy

Industry

Infrastructure

Transport

Transport in Duran is primarily dependent on the road system, due to mountainous terrain which is not particularly suitable for rail transport. As a historic overland route for trade between Shangea and Satria, Duran's central route road has been used for millenia. This road, as well as other key routes such as the corridoor between Chenpodrang and the border with Ansan, are well maintained and wide. However, in rural areas, the state of roads is often of a far lower quality. This is especially true of the Tribal autonomous regions, which are far poorer than the rest of the country and economically disadvantaged. Road travel has historically been threatened by instability within the country, though in the modern day this is limited. Duran maintains road crossings with all of its neighbours, though the Shangean crossings have been closed briefly during periods of tension. Intercity busses are a major form of transportation in the country.

Despite its terrain, Duran does maintain a rail network which links the major lowland and midland cities. Initially centred upon Chenpodrang, the network has grown over the years with a connection now to Luquzo in the south of the country. Duran's rail system has struggled with a lack of funding, and has in many cases depended on funding through ComDev as seen with the rail link to Ansan which then links to ports. This link has recieved major investment as it is the only way for landlocked Duran to connect with Senria, who is a major partner. Of Duran's cities, only Chenpodrang has a metropolitan railway. Built in the 1970s, it has struggled with age related issues but is still important for local transportation.

Air travel is another aspect of the country's transport system. Chenpodrang International Airport is the country's major international airport, though several smaller airports also take short distance cross border flights. Domestic air travel is a developing part of the transport network, primarily popular for accessing areas such as Syrqindo which are seen to be dangerous for overland travel.

Demographics

Education

Religion

Religion has played a major formative role in Duran's political and social history, and the country is still associated with religiousity. Part of this connotation is an attribution which was deliberately perpetuated by the Duranian Exile Government and which has been maintained as a tourist atout. The imagery of Duran as a sort of peaceful Shangri-La of Zohist monasticism has been criticised in recent years, however, as it is seen as a form of normative erasure of the many traditional faiths of the hill peoples as well as other religious communities which have existed in Duran for generations.

Though not the oldest religion in Duran, Zohism has been the faith which has dominated sedentary Namkha society since the rise of the Namrong dynasty as the dominant valley state among the Duranian peoples. Zohism is based upon the teachings of Soucius, a 7th century BCE Shangean philosopher who was highly critical of the dominant religions in the area. Despite repression by imperial authorities, the religion spread rapidly. Though records are limited, it is believed that Zohism first arrived in what is now Duran around 500 CE. It is generally considered to have converted the Namrong elite through mercantile connections, though some historians have instead postulated that it was brought by Shangean mercenaries who established the initial Namrong state. In any case, the religion represented an established minority by the time the Namrong dynasty emerged and would grow quickly through state patronage. Initially, Zohism's practice in Duran was highly syncretic and absorbed elements from local beliefs until it had strayed far from the original faith. However, during the reign of Khyungchen Dingba in the first century BCE there was a concerted effort by the state to restore a doctrinal orthodoxy. He sent a young monk named Orgyen Phuntsok south, tasked with retrieving authentic texts from Shangea. Details of this journey have become the semi-mythical Great Southern Journey, in itself an early religio-cultural narrative important in Duran's national identity. Phuntsok was labelled as a Tertön and is still revered as the father of Duranian Zohism, while the teachings which he elaborated went on to create a national standard of belief which would influence the later emergence of the Tsandau orthodoxy. This orthodoxy would dominate the upper classes and be influential over official culture, art, and architecture, though more syncretic practice remained present among common people.

For the early Namrong and Karpoja states, the Zohist clergy were the only ones who were literate and therefore were highly important for administration. This, combined with personal piety and a desire for religious legitimacy, led to the monarchy confiding power into the hands of local monasteries. Similar to in the Svai Empire, Sengshui became deeply rooted, with the nation's aristocracy essentially being composed of monks or ex-monks. In the fourth century CE, the central government of the Karpoja Kingdom collapsed, leading to a period of anarchy in which the fortress-monasteries became the sole political authorities. When stability was restored, it was under a theocratic rule by the Zhabrung Rinpoche, who combined political and religious rule. Though the centre of this authority has shifted, power has remained centred upon the clergy for most of Duran's history. Much of Duran's national culture, such as its arts and literature, are deeply influenced by Zohist aesthetics and themes. Zohism is practiced by 79% of the nation's population according to census data. However, as in Senria and many other South Coian states, this figure includes many wh associate themselves both with being Zohists and other religions. Sectarian data is not collected, but the dominant school remains the Tsandau.

Duran is also home to a vast variety of traditional faiths practiced by the hill tribes, many of which are based upon beliefs which predate Zohism's arrival in Duran. The largest of these traditional faiths is Kadawism, which is practiced by the Hua people. Kadawism is an animist and polytheistic religion centred upon the worship of spirits known as Da, which are believed to be the reincarnations of sinners which are forced to wander earth until they can aid enough people to gain access to a new life. Kadawism is based strongly on small scale offerings and rituals, with larger ceremonies being led by shamans called Kadaw. Another major ethnic faith is Momism, which is the traditional faith of the Ro people. Momism is more organised than other traditional faiths, with holy texts and a structured clergy. It emerged out of an earlier animist tradition, but took on elements of millenarianism following the defeat of the Black Turban Revolt in the 17th century. Momists believe that the leader of this revolt, the preacher Hni Wo, was the promised Just King and that he will return to bring about an era of peace and prosperity on earth. Since the 1970s, the Ro Salvation Socialist Front has been waging war against the central government, hoping to establish a state for this king to rule. Other hill peoples have their own traditional religions.

Other world religions present in Duran include Irfan and Sotirianity. Irfan first arrived in Duran with Pardaranian merchants, maintaining a limited presence in the capital city. This community was small and did not include many converts, as they were forced to live away from the main population in a walled compound. However, as time went on, the Irfanic community gradually moved from segregation into being a highly successful mercantile community. Chenpodrang's Irfanic Quarter of Khyétsarpo Duklok became a thriving area and the Bahram family became some of the most important people in the kingdom. Though they faced oppression during the Shangean occupation, the Irfanic community has remained present. Sotirianity is a recent arrival to Duran and is concentrated among the Gie people, who were converted to Episemialism by Soravian missionaries in the 1950s. Various Satrian religions also have a presence thanks to migration, particularly from Ajahadya, as does Tenkyou and other religions concentrated in immigrant populations.

Culture

Music and Art

Cuisine

As a highly diverse nation, Duran is blessed with a range of different culinary traditions which reflect the different means of subsistence of the nation. These differences in subsistence form the basis for the three major schools of Duranian cuisine. The first of these schools is the Tsampa school, which is sometimes referred to as "Nampa cuisine" though this designation is simplistic. This culinary school is based upon the cultivation of barley, and uses barley-based flour called tsampa. This is then turned into noodles or momos, which are some of the most emblematic Duranian dishes. The second school, known as Zhukme cuisine, is based on the cultivation of rice in the lowlands of the country. This cuisine is the most fusional of the three schools, and takes strong inspiration from Shangean cuisine. This schools name, Zhukme, literally translates to "fire" because of the prominent use of chillies to add heat to dishes. The final school is the Tsokpa school, which is primarily that of the hill tribes. Tsokpa cuisine is based upon the cultivation of tubers and other such crops instead of more sedentary staples, as well as herbs and spices.

Meat plays a key role in Duranian cuisine across all three schools, especially the Tsampa and Tsokpa. This is because, outside of the fertile valleys of the lowlands which permit regular cultivation of staple crops, growing conditions are not stable and meat is needed for protein. Milk and its derivatives are also central to much of Duranian cuisine and culture. Yak, Takin and Goat are the most common types of milk. A popular drink consumed in Duran is butter tea, which is drunk by the vast majority of Duranian people on a daily basis. Cheeses are also made, especially by the Yagpa people who often sell their products in the major cities.

Alcoholic beverages are also widely consumed. Chang, a domestically made barley beer, is the most popular drink, but fermented milk, rice wine and others are also popular. While Duran is a significant producer of traditional alcoholic beverages, mass-marketed beers from neighbouring Shangea dominate much of the market due to their low price.