Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 122: | Line 122: | ||

This critique was most famously made by [[Adelaja Ifedapo]] in his early Pan-Bahian work ''Houreges and Colonizers: A History of the [[Sougoulie]] Rebellion''—whose thesis dominates Asalewan {{wp|historiography}} of Bahian history and is the Asalewan Section's position on the subject to this day—which advanced the notion that the cause of the Sougoulie's failure, and the [[Toubacterie]] more broadly, was primarily internal rather than external; he argued that rebels' failure to unite across tribal lines or arouse widespread support amongst the lower classes were the primary reasons for their failure. He also especially, argued that the primary source of Bahia's historic underdevelopment, enabling military conquest in the first place, was the [[Hourege|Houregic]] system; unlike in Euclea, where an emergent {{wp|bourgeoisie}} had a strong interest in economic development and industrialization, he argued that Bahian elites' historic dependence on land and slave ownership, particularly the lucrative [[Transvehemens slave trade]], meant they were uninterested in economic development. Adelaja and other members of the Asalewan Section held that the emergent {{wp|lumpenbourgeoisie|national bourgeoisie}}, studied through the lens of {{wp|comprador|plantation administrators and traders in colonial-era cities}}, was also incapable of spurring substantial economic development as that would necessitate confrontation with the Euclean capitalists upon whom mthey depended. Accordingly, their preferred solution to this underdevelopment and geopolitical weakness was in tandem with the rest of the Asalewan Section's political agenda, namely {{wp|social revolution}} and intense {{wp|class struggle}} against pre-colonial and native elites just as much as against the [[Estmere|Estmerish]] {{wp|White Highlands|colonial landowning class}}. | This critique was most famously made by [[Adelaja Ifedapo]] in his early Pan-Bahian work ''Houreges and Colonizers: A History of the [[Sougoulie]] Rebellion''—whose thesis dominates Asalewan {{wp|historiography}} of Bahian history and is the Asalewan Section's position on the subject to this day—which advanced the notion that the cause of the Sougoulie's failure, and the [[Toubacterie]] more broadly, was primarily internal rather than external; he argued that rebels' failure to unite across tribal lines or arouse widespread support amongst the lower classes were the primary reasons for their failure. He also especially, argued that the primary source of Bahia's historic underdevelopment, enabling military conquest in the first place, was the [[Hourege|Houregic]] system; unlike in Euclea, where an emergent {{wp|bourgeoisie}} had a strong interest in economic development and industrialization, he argued that Bahian elites' historic dependence on land and slave ownership, particularly the lucrative [[Transvehemens slave trade]], meant they were uninterested in economic development. Adelaja and other members of the Asalewan Section held that the emergent {{wp|lumpenbourgeoisie|national bourgeoisie}}, studied through the lens of {{wp|comprador|plantation administrators and traders in colonial-era cities}}, was also incapable of spurring substantial economic development as that would necessitate confrontation with the Euclean capitalists upon whom mthey depended. Accordingly, their preferred solution to this underdevelopment and geopolitical weakness was in tandem with the rest of the Asalewan Section's political agenda, namely {{wp|social revolution}} and intense {{wp|class struggle}} against pre-colonial and native elites just as much as against the [[Estmere|Estmerish]] {{wp|White Highlands|colonial landowning class}}. | ||

In destroying the socioeconomic structures held to result in Bahia's historic underdevelopment, however, the Asalewan Section held, in accordance with the traditional {{wp|Marxism|Nemtsovite}} model of {{wp|base and superstructure}}, that a struggle against preexisting the class base also necessitated a struggle against the {{wp|reactionary}} social superstructure that supported and reinforced this class base, and the total destruction of this superstructure just as there must be a total destruction of the class base that birthed it. | In destroying the socioeconomic structures held to result in Bahia's historic underdevelopment, however, the Asalewan Section held, in accordance with the traditional {{wp|Marxism|Nemtsovite}} model of {{wp|base and superstructure}}, that a struggle against preexisting the class base also necessitated a struggle against the {{wp|reactionary}} social superstructure that supported and reinforced this class base, and the total destruction of this superstructure just as there must be a total destruction of the class base that birthed it. Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism's radical modernism and class politics resulted, also, in an equally-radical {{wp|social progressivism}}, manifesting itself most prominently in {{wp|state atheism}}, {{wp|Marxist feminism|Nemtsovite feminism}}, and advocacy of {{wp|Family#Criticism|family abolition}}. | ||

[Section | ===="Primitive Modernism"==== | ||

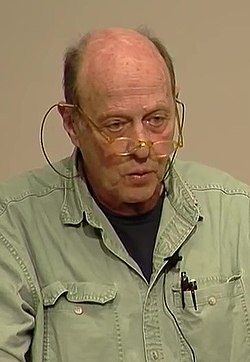

[[File:James C Scott 2016.jpg|thumb|left|250px|In his book {{wp|Seeing Like a State|Planners and Peasants}}, the [[Gaullica|Gaullican]] {{wp|anthropology|anthropologist}} {{Wp|James C. Scott|Jaques Legalle}}, a noted scholar of stateless communities in the Asalewan Highlands and South Coius, analyzed the ways that the Asalewan Section sought to co-opt stateless and peasant communities' rituals in service of a modernist, centralizing vision frequently hostile to those communities.]] | |||

Despite the ideology's fundamentally modernist nature, some scholars have argued that the Asalewan Section, and Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Tretyakism, in practice co-opted aspects of Asalewan traditional culture—especially that of the [[Lowland-Highland Divide (Asase Lewa)|Asalewan Highlands]], much of which featured stateless, communal social structures seen by the Asalewan Section as a degenerated form of {{wp|promitive communism}}—into its modernist and revolutionary ambitions. [[Valduvia|Valduvian]] scholar of Bahian and Asalewan politics Algirdas Jancius especially argued that this was the case during the Asalewan Revolution. Most famously, Jancius connected the People's Revolutionary Army's extensive usage of {{wp|suicide attacks}} during the Revolution—and in later conflicts, especially during the Protective-Corrective Revolution and the PRA's support for insurgents during the [[Tiwura#Post-Independence|First Tiwuran Civil War]], but continuing during the [[Tiwura#Chipo's Rule|Second Tiwuran Civil War]] and [[Lokpaland insurgency]]—to an extensive tradition of ritualized suicide attacks and {{wp|altruistic suicide}} in traditional Asalewan war cultures, especially in conflicts at the fringes of Highlander and Lowlander societies. | |||

Jancius also discussed, as have scholars such as the [[Gaullica|Gaullican]] {{wp|anthropology|anthropologist}} {{Wp|James C. Scott|Jaques Legalle}}, the Asalewan Section's extensive adoption and radicalization of other traditional cultural practices, especially its adoption of organization and rituals modeled after Asase Lewa's [[Sodality (Bahia)|sodal]] {{wp|secret societies}}, not least since sodal secret societies were the structure its members were most familiar with that preserved some secrecy. In addition to partly modelling the Section off the sodal secret societies, Revolution-era leaders of the Asalewan Section, including Adelaja Ifedapo and Edudzi Agyeman themselves, actively discussed aspects of quasi-stateless Highlander society, especially {{wp|direct democracy|direct democratic}} {{wp|Panchayat|village councils}} and {{wp|collective farming|communal ownership of land}}, as legacies of {{wp|primitive communism}} that were worthy of defending from colonialism and of integrating into councilist modernity, if under very different and much more egalitarian terms than they actually existed as. | |||

{{Quote box | |||

|class = <!-- Advanced users only. See the "Custom classes" section below. --> | |||

|title = | |||

|quote = It is true that if we sat back, if we did not struggle and fight even if we do not presently risk martyrdom is lower than it was before we arrived at {{wp|Yan'an|Lokossa}}, if we did not seek to develop the productive forces, if we retreated into primitive communism as the utopian socialists did before Nemtsov's scientific discoveries, we would betray the proletariat, we would bring about our own doom, we would do nothing to begin humanity's true history, to establish councilism and communism. Looking too much to Bahia, or [[Abidemism|within the soul]], has left some of our comrades blind in one eye, blind to the [[Estmere|stag]] that stalks us, or the horizon of global councilism and communism when we need not fear it. But in their haste to avoid primitive communism, many of our comrades ignore the only example of living councilism and communism in Bahia and the colonies. Looking too much to Euclea, and to the productive forces, has left them, too, blind in one eye. They look so much to Euclea that they risk slipping into [[Equalism]] or worse, {{wp|social democracy}}. When these comrades ask, then, "What will councilism look like? Can humanity really create communism?", they need look no further what they they can glimpse with their own eyes, but are too blind oo see: to the village councils here in Lokossa, where all have an equal voice, the {{wp|age set|men from different mothers and fathers}} living and working together in harmony and brotherhood, the feasts in times of plenty or rations in times of dearth, where all have a share. This is the dictatorship of the proletariat. This is councilism. And when our heroes and martyrs melt the {{wp|manilla (money)|manilla}}, burn {{wp|Asantehene|the Golden Stool}}, and slay the stag, this will be communism! | |||

|author = Edudzi Agyeman | |||

|source = ''Rectifying Dogmatist Errors in our Section'', May 17, 1938. | |||

|align = right | |||

|width = 50% | |||

|border = | |||

|fontsize = | |||

|bgcolor = | |||

|style = | |||

|title_bg = | |||

|title_fnt = | |||

|tstyle = | |||

|qalign = | |||

|qstyle = | |||

|quoted = | |||

|salign = | |||

|sstyle = | |||

}} | |||

Jancius termed this co-option of traditional cultures in service to a revolutionary modernist vision "Primitive Modernism," comparing the early Section to peasant {{wp|millennarianism|millennarian}} and early {{wp|working-class}} movements that {{wp|Primitive Rebels|extensively deployed quasi-religious rhetoric, pomp, and traditionalistic ritual}} but distinguishing the Section from these movements insofar as the Section was and is a much more modern and centralized revolutionary force that developed a much more coherent and complex ideology and social structure that broadly supported, rather than resisted, centralization and modernization; Jancius also discussed the Section's origins in the colonized {{wp|intelligentsia}} and {{wp|labour aristocracy|upper echelons of the colonized working-class}} that only later appealed to subaltern elements such as the colonized peasantry, rather than originating in the peasantry as these movements largely did. | |||

Despite this co-option of certain traditional structures during the Revolution, most scholars, including Jancius and Legalle, have still identified the Asalewan Section and Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism as fundamentally modernist. This is because the Section's adoption of traditional practices decreased over time; for example, throughout the Revolution the Section gradually though not entirely replaced the sodal secret societies' highly ritualistic form of secrecy, in some ways more symbolic than real, with a {{wp|clandestine cell system|cell-based form of organization}} inspired by other councilist guerrillas in highly repressive conditions, such as the [[Voyins]] and [[East Miersa|Miersan partisans]]. Jancius and Legalle especially argued that the Section's modernist nature particularly became apparent after the Revolution's victory, when the Section became far less dependent on the support of forces attached to traditional practices, such as Highlander chiefs and {{wp|big man|big men}}, and could thus survive their resistance to its centralizing and modernist ambitions. During the 1950s and 1960s, particularly during the [[Asase Lewa#Bahian People's Republic and the Socialist Developmental State|Anti-Tribal Revolution]] of 1958-1963, this entailed dramatic measures including a continuation and intensification of colonial-era {{wp|sedentarization}} programs as one step towards {{wp|collective farming|agricultural collectivization}}, standardization of Asase Lewa's five official languages along the lines of dialects spoken in urban or dense rural areas, the prohibition of certain traditional practices such as {{wp|female genital mutilation}}, mandating villages pay high taxes to fund expensive industrial, infrastructure, and social campaigns, and the compulsory integration of many sodal secret societies into the Asalewan Section's mass organizations. | |||

Despite such measures and radical attacks on Asalewan traditional society, including Highlander society, most scholars have still argued that the Asalewan Section still practiced limited co-option of traditional values and communities, which the Asalewan Section and Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists themselves continued to embrace in a limited form. In 1961, for example, Edudzi Agyeman argued that "our village councils, our sodalities, our communities—these will, once cleansed from tribalist and comprador-bourgeois filth, work with our mass organizations and our Section to create an unbreakable bond that will carry us into councilism and communism." These scholars have argued that this rhetoric still matched reality; for example, in his book ''{{wp|Seeing Like a State|Planners and Peasants}}'', Legalle argued that many Asalewan {{wp|high modernism|high modernist}} worldmaking projects during this period, most of which involved organizing people into modernist, nationwide communal and collective associations or structures, were somewhat more successful than most high modernist projects because they established traditional structures as the building-block of such associations. | |||

Legalle especially discussed the Asalewan state's co-option of {{wp|age sets}} as the building blocks of {{wp|kibbutz|communal villages and neighborhoods}} in which {{wp|Kibbutz communal child rearing and collective education|childrearing, education, housework, and all other social reproduction would be done communally outside the family unit}}; in areas in which age sets were a traditional social structure, the Asalewan state largely allocated and segregated communal housing and labor tasks according to traditional age sets. Moreover, Legalle noted that in regions in which age sets became the building block of commune life, communes' collectivization of social reproduction encountered far less resistance, and has been far more likely to be retained until the modern day, than in regions where this was not the case. While the co-option of age sets into communal life was the Asalewan Section and state's most notable co-option of traditional community structures, Legalle argued that this was a widespread phenomenon, particularly in modernizing campaigns and programs heavily modified or adopted (as communes were) after the [[Protective-Corrective Revolution]], which embraced Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism but led to the ideology developing a focus, at least nominally, on local democracy, which Jancius termed "councilist {{wp|subsidiarity}}." | |||

As examples, Legalle discussed the integration of sodal secret societies into the Asalewan Section's mass organizations—complete with different mass organizations' local branches adopting rituals and symbols based on those of their sodal secret society—as well as the creation of "{{wp|Communal Councils (Venezuela)|communal}} Workers' Councils" as the building block of the state in the [[Constitution of Asase Lewa|1969 Constitution]], communal councils designed to closely correspond to the size and scale of traditional Highlander village councils. Legalle also disaagreed with Jancius in arguing that the Section itself's abandonment of traditional, sodal-esque was not as complete as Jancius argued. Whereas the Section did indeed rely on cell-based organization to ensure its secrecy during the Asalewan Revolution, Legelle discussed the ways in which local Section branches in the Highlands, continue to use things such as sodal-esque initiatory rites when onboarding new members, or members donning special masks and uniforms—a hallmark of the sodal socieites—during special rituals, especially {{wp|International Workers' Day}}. | |||

====Feminism==== | ====Feminism==== | ||

| Line 166: | Line 204: | ||

However, Edudzi Agyeman himself, and Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists more broadly, rejected this conclusion. Instead, Edudzi argued that, in much the same way as the {{wp|proletariat}} constituted the {{wp|universal class}}, whose interests were identical to those of humanity as a whole because their emancipation as a class could not come without the emancipation of humanity as a whole through the establishment of a {{wp|communist society|communist}} {{wp|classless society}}, Bahians constituted the "universal nation" and the "universal race," whose interests as a nation and race were indistinguishable from the colonized, the proletariat, or humanity as a whole. Edudzi argued that this was the case because Bahians collectively lacked a particular cultural heritage, with all the particular sectional, non-universal interests that implies—with such heritage only being held by Bahian sub-groups (in the same way that the proletariat collectively had no particular interests even if subsections of the proletariat do), and even that heritage having been seriously eroded during the Toubacterie—and because Bahians were, by definition, inherently oppressed under the capitalist {{wp|world-system}}, thus having no choice but to agitate against it, at all times and without qualifications. | However, Edudzi Agyeman himself, and Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists more broadly, rejected this conclusion. Instead, Edudzi argued that, in much the same way as the {{wp|proletariat}} constituted the {{wp|universal class}}, whose interests were identical to those of humanity as a whole because their emancipation as a class could not come without the emancipation of humanity as a whole through the establishment of a {{wp|communist society|communist}} {{wp|classless society}}, Bahians constituted the "universal nation" and the "universal race," whose interests as a nation and race were indistinguishable from the colonized, the proletariat, or humanity as a whole. Edudzi argued that this was the case because Bahians collectively lacked a particular cultural heritage, with all the particular sectional, non-universal interests that implies—with such heritage only being held by Bahian sub-groups (in the same way that the proletariat collectively had no particular interests even if subsections of the proletariat do), and even that heritage having been seriously eroded during the Toubacterie—and because Bahians were, by definition, inherently oppressed under the capitalist {{wp|world-system}}, thus having no choice but to agitate against it, at all times and without qualifications. | ||

Edudzi, and Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists more broadly, thus argued in favor of Pan-Bahianism not on the basis of a common cultural heritage, but as an extension of their proletarian internationalism; they believed that any Pan-Bahian state dominated by the Bahian {{wp|proletariat}} would have no choice but to pursue universal and pure proletarian internationalism, even moreso than other socialist countries that, though following broadly proletarian internationalist foreign policies, might sometimes pursue the particular interests of their country's working-class and in that way betray the proletariat and humanity as a whole. With a socialist {{wp|world government}} appearing to be only a distant, long-term goal, the Asalewan Section of the Workers' International agitated for a Pan-Bahian state as something that could be achieved in the short-term and have the same proletarian internationalist foreign policy of, and strike directly at the heart of the capitalist world-system in the same way as, a global socialist state. Many academics, such as [[Valduvia| | Edudzi, and Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists more broadly, thus argued in favor of Pan-Bahianism not on the basis of a common cultural heritage, but as an extension of their proletarian internationalism; they believed that any Pan-Bahian state dominated by the Bahian {{wp|proletariat}} would have no choice but to pursue universal and pure proletarian internationalism, even moreso than other socialist countries that, though following broadly proletarian internationalist foreign policies, might sometimes pursue the particular interests of their country's working-class and in that way betray the proletariat and humanity as a whole. With a socialist {{wp|world government}} appearing to be only a distant, long-term goal, the Asalewan Section of the Workers' International agitated for a Pan-Bahian state as something that could be achieved in the short-term and have the same proletarian internationalist foreign policy of, and strike directly at the heart of the capitalist world-system in the same way as, a global socialist state. Many academics, such as [[Valduvia|Algirdas Jancius]], have thus argued that Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism paradoxically advocates a sort of of "internationalist nationalism," seeking to construct a particular national community precisely because that community's interests would be indistinguishable from humanity as a whole. | ||

However, many academics have also questioned the extent to which the modern-day Asalewan Section of the Workers' International, and Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists more broadly, adhere to "internationalist nationalism." These academics, including Jancius himself and the [[Estmere|Estmerish]] scholar of Bahian politics Gary Carter, have argued that the Asaslewan Section and state has, in the wake of the United Bahian Republic's dissolution and the collapse of other socialist Bahian states more broadly, increasingly focused on advancing Asase Lewa's particular interests internationally while increasingly seeking to construct a common national identity domestically, such as by seeking to create a common ''lingua franca'' in the form of {{wp|Ewe language|Asalewan}} and by increasingly valorizing aspects of Asase Lewa's traditional and pre-colonial culture, especially its {{wp|folk art}} and {{wp|folk culture}}. While Asase Lewa's foreign policy remains in many ways proletarian internationalist and Pan-Bahian, and while its {{wp|nationbuilding}} efforts retain a distinctly anti-colonial and socialist character, such policies do not retain the specific emphasis on advancing ''only'' the interests of the universal Bahian and proletarian communities seen in the mid-century Asalewan Section of the Workers' International. | However, many academics have also questioned the extent to which the modern-day Asalewan Section of the Workers' International, and Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists more broadly, adhere to "internationalist nationalism." These academics, including Jancius himself and the [[Estmere|Estmerish]] scholar of Bahian politics Gary Carter, have argued that the Asaslewan Section and state has, in the wake of the United Bahian Republic's dissolution and the collapse of other socialist Bahian states more broadly, increasingly focused on advancing Asase Lewa's particular interests internationally while increasingly seeking to construct a common national identity domestically, such as by seeking to create a common ''lingua franca'' in the form of {{wp|Ewe language|Asalewan}} and by increasingly valorizing aspects of Asase Lewa's traditional and pre-colonial culture, especially its {{wp|folk art}} and {{wp|folk culture}}. While Asase Lewa's foreign policy remains in many ways proletarian internationalist and Pan-Bahian, and while its {{wp|nationbuilding}} efforts retain a distinctly anti-colonial and socialist character, such policies do not retain the specific emphasis on advancing ''only'' the interests of the universal Bahian and proletarian communities seen in the mid-century Asalewan Section of the Workers' International. | ||

Latest revision as of 10:11, 31 January 2024

Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism, sometimes referred to simply as Adelajism-Edudzism is a Nemtsovite and Councilist ideology developed by the Asalewan Section of the Workers' International that synthesizes Nemtsovism and Councilism with Tretyakism, Pan-Bahianism, various anti-colonial ideologies that proliferated in Coius, and the theories of the Asalewan Section's historic leading figures Adelaja Ifedapo and Edudzi Agyeman. Ideologically, Nemtsovism-Adelajism-Tretyakism-Edudzism departs from Nemtsovite and Councilist orthodoxy in that it embraces Pan-Bahian nationalism, a quasi-humanistic interpretation of Nemtsovism, a limited role for a post-revolutionary vanguard, and Tretyakist ideas favoring militarism. Nemtsovism-Adelajism-Tretyakism-Adelajism is also distinct in that it views the colonized peasantry, lumpenproletariat, and hunter-gatherers, not just the working-class, as a part of the proletariat and thus aa revolutionary class. Though named after Yuri Nemtsov, Konstantyn Tretyak, Adelaja Ifedapo, and Edudzi Agyeman, and drawing substantial influence from their ideas, the ideology differs from all the personal beliefs of four thinkers, particularly Nemtsov and Tretyak. Traditionally, the Asalewan Section has regarded the ideology not as a universally-applicable development of Nemtsovism and Councilism, but rather a specific application of those ideologies to Asalewan and Bahian material conditions, and thus an ideology needing constant ideological development and advancement in response to changes in those material conditions.

Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism traces its origins to the synthesis of Nemtsovism and Pan-Bahianism practiced by the early Asalewan Section in the 1910s, a synthesis primarily formalized through the writings of Adelaja Ifedapo. In the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, the ideology became substantially modified by Adelaja and Edudzi Agyeman as the Asalewan Revolution turned its focus to the peasantry and hunter-gatherers and as self-reproducing hierarchical military and party structures led to an increasingly authoritarian and quasi-Equalist turn. The violent, militaristic nature of the Asalewan Revolution and the mass militarization in the 1950s and 1960s caused the Section to adopt Tretyakist ideas, and the collapse of the United Bahian Republic and Protective-Corrective Revolution returned Councilism to the center stage and introduced the theory of Perpetual-Cyclical Revolution to the ideology.

History

Principles

Nemtsovism

Taking its name from the the ideology's namesake, and influenced by Adelaja Ifedapo and other members of the left-wing Asalewan intelligentsia's experience in Nemtsovite Estmerish political parties, first Social Democracy of Estmere and then the Estmerish Section of the Workers' International, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism views itself as a development of Nemtsovism and correct application of Nemtsovite theory to Asalewan and Bahian material conditions. Consequently, Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism incorporates numerous aspects of Nemtsovite orthodoxy as central to the ideology, including a materialist interpretation of history, dialectical analysis of social relations and transformation, a belief that a society's economic base determines its cultural, social, and political superstructure, and an emphasis on the centrality of class struggle, including the central emancipatory role of the proletariat and support for an international proletarian revolution.

Similar to many other Coian revolutionary movements, however, Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism rejects Classical Nemtsovism, Nemtsov's writings as unmodified from their original forms, and Orthodox Nemtsovism, a body of Nemtsovite thought popular in the early Euclean social-democratic and councilist ideological milieu, including Social Democracy of Estmere and the Estmerish Section, that many founders of the Asalewan Section and early theoreticians of Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism emerged from. Rejecting Orthodox Nemtsovism and many aspects of Nemtsovite and councilist orthodoxy developed by Valduvian Nemtsovologists after that country's revolution, Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism instead embraces a humanistic and pragmatic view of Nemtsovism, inspired by certain theoreticians of Eastern Nemtsovism and Adelaja Ifedapo's own interpretation of the ideology. In his 1938 text Nemtsov in the Colony, Adelaja argues that, rather than being a fixed body of knowledge as in Orthodox Nemtsovism, Nemtsovism is properly understood as maintaining the theory's historical and dialectical materialist core but producing analytic results and knowledge that may differ drastically across time and place.

In the Bahian and Asalewan case, Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists argue, these differing analytic results include viewing the Bahian, colonized peasantry, lumpenproletariat, and even hunter-gatherers as revolutionary classes on the level of the working-class. While many Nemtsovite parties and movements have historically sought to organize these classes as junior parts of a united front led by the workiing-class, which retains a leading, vanguard role, Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzism is distinct in that views these classes as equal, not subordinate, to the working-class in the revolutionary struggle. Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists do not disagree with Nemtsovism's view that the proletariat is a revolutionary universal class because it lacks, as a class, any particular interests or attachments to property and hierarchical social relations. Rather, it argues that the conditions of Bahia's colonization were such that all members of colonial-era Bahian lower classes were proletarians.

Adelaja Ifedapo, Nemtsovism in the Colony, February 11, 1937.

Such an analysis was partly rooted in materialist arguments about Bahian material conditions under colonialism; particularly in colonial Asase Lewa, the colonial state rapidly reorganized agricultural labor from being done by peasant smallholders to being done by wage laborers on plantations, which Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists considered the establishment of a rural proletariat, geographically but not sociologically from the urban proletariat of Euclea. However, Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists expanded upon these arguments to ones rooted in Nemtsovite humanism, as many Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzist theorists, including Adelaja Ifedapo and Edudzi Agyeman themselves, argued that the extreme alienation and dehumanization–that colonial society induced in the colonized—through the psychopathology of violence and humiliation as much as economic proletarianization—violently stripped the colonized, including the Bahian peasanatry, lumpenproletariat, and hunter-gatherers, from any particular interests that might prevent them from becoming part of the universal, revolutionary class of the proletariat.

Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism also shares a belief in the power of bourgeois cultural hegemony, a theory developed by Estmerish Nemtsovite Jürg Ochsner and shared by many Eastern Nemtsovites and Nemtsovite humanists that bourgeois cultural power and ideology, in both the metropole and the colonies, as a key force preventing the development of proletarian class consciousness. Though arguing that the naked reality of colonial violence and extraction means that it is much more difficult for the bourgeoisie to impose cultural hegemony in the colony than the metropole, Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism does believe that bourgeois, colonial cultural hegemony is an important force preventing the development of anti-colonial consciousness in the more privileged segments of the colonized, especially the colonized intelligentsia, labor aristocracy, and other elements of the native populations broadly assimilated into colonial society. Consequently, Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists favor the element of a proletarian cultural hegemony, expressed in the colonized and Bahian world as the development of a distinctly proletarian and indigenous national culture and sense of national community, albeit with little relation to pre-colonial Bahian society, which Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists disdained as weak and easily-conquered, and tinged with a distinctly proletarian internationalist spirit.

Despite its humanistic and Eastern Marxist influences, Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism does not totally embrace the Nemtsovist humanist tradition. Most prominently, the ideology retains the belief, as in classical Nemtsovism, that dialectical materialism can and ought to be applied to the natural sciences just as much as the social sciences. Even though Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism's primary focus is on the social conditions of Asalewan and Bahian society, this belief has had an important influence on the ways science has been applied in Asase Lewa since the Asalewan Revolution. In addition to substantially applying the Nemtsovist dialectic to scientific inquiry, post-revolutionary Asalewan science has been characterized, in concert with Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzist beliefs in the mass line as key to solving and understanding scientific problems as well as social ones, by an emphasis on "mass science", characterized by an emphasis on science that would fulfill immediate, practical aims, participation of scientists in manual labor, mass peasant and proletarian participation in scientific experiments, large-scale science and technical education, and the limited incorporation of folk knowledge into the broader body of scientific knowledge.

Councilism

"Illiberal Councilism"

Militarism

Collectivism

[In contrast to most aspects of the ideology, glorification of communal childrearing structures and land ownership as vestiges of the Sâretic, primitive communist past, and thus indications of the direction that the communist future ought to go in]

Progressivism and Modernity

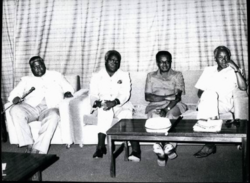

Adelaja Ifedapo, Houreges and Colonizers: A History of the Sougoulie Rebellion, August 16, 1896.

In concert with the global consensus of the socialist left in the Three Tenets, and with many developmentalist and nationalist ideologies in other late-industrializing or colonized states, such as Sattarism, Imaharism, or National Principlism, Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism presents itself as fundamentally progressive and modernist. However, in staunch contrast with many Bahian socialists, or even palingenetic anti-colonial nationalists, who at some level elevated a perceived pre-colonial past, Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism harshly criticized pre-colonial Asalewan and Bahian formations as responsible in large part for the region's chronic underdevelopment and ability to be subordinated to Euclean powers, and thus called for a total rupture between pre and post-colonial social and cultural structures.

This critique was most famously made by Adelaja Ifedapo in his early Pan-Bahian work Houreges and Colonizers: A History of the Sougoulie Rebellion—whose thesis dominates Asalewan historiography of Bahian history and is the Asalewan Section's position on the subject to this day—which advanced the notion that the cause of the Sougoulie's failure, and the Toubacterie more broadly, was primarily internal rather than external; he argued that rebels' failure to unite across tribal lines or arouse widespread support amongst the lower classes were the primary reasons for their failure. He also especially, argued that the primary source of Bahia's historic underdevelopment, enabling military conquest in the first place, was the Houregic system; unlike in Euclea, where an emergent bourgeoisie had a strong interest in economic development and industrialization, he argued that Bahian elites' historic dependence on land and slave ownership, particularly the lucrative Transvehemens slave trade, meant they were uninterested in economic development. Adelaja and other members of the Asalewan Section held that the emergent national bourgeoisie, studied through the lens of plantation administrators and traders in colonial-era cities, was also incapable of spurring substantial economic development as that would necessitate confrontation with the Euclean capitalists upon whom mthey depended. Accordingly, their preferred solution to this underdevelopment and geopolitical weakness was in tandem with the rest of the Asalewan Section's political agenda, namely social revolution and intense class struggle against pre-colonial and native elites just as much as against the Estmerish colonial landowning class.

In destroying the socioeconomic structures held to result in Bahia's historic underdevelopment, however, the Asalewan Section held, in accordance with the traditional Nemtsovite model of base and superstructure, that a struggle against preexisting the class base also necessitated a struggle against the reactionary social superstructure that supported and reinforced this class base, and the total destruction of this superstructure just as there must be a total destruction of the class base that birthed it. Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism's radical modernism and class politics resulted, also, in an equally-radical social progressivism, manifesting itself most prominently in state atheism, Nemtsovite feminism, and advocacy of family abolition.

"Primitive Modernism"

Despite the ideology's fundamentally modernist nature, some scholars have argued that the Asalewan Section, and Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Tretyakism, in practice co-opted aspects of Asalewan traditional culture—especially that of the Asalewan Highlands, much of which featured stateless, communal social structures seen by the Asalewan Section as a degenerated form of promitive communism—into its modernist and revolutionary ambitions. Valduvian scholar of Bahian and Asalewan politics Algirdas Jancius especially argued that this was the case during the Asalewan Revolution. Most famously, Jancius connected the People's Revolutionary Army's extensive usage of suicide attacks during the Revolution—and in later conflicts, especially during the Protective-Corrective Revolution and the PRA's support for insurgents during the First Tiwuran Civil War, but continuing during the Second Tiwuran Civil War and Lokpaland insurgency—to an extensive tradition of ritualized suicide attacks and altruistic suicide in traditional Asalewan war cultures, especially in conflicts at the fringes of Highlander and Lowlander societies.

Jancius also discussed, as have scholars such as the Gaullican anthropologist Jaques Legalle, the Asalewan Section's extensive adoption and radicalization of other traditional cultural practices, especially its adoption of organization and rituals modeled after Asase Lewa's sodal secret societies, not least since sodal secret societies were the structure its members were most familiar with that preserved some secrecy. In addition to partly modelling the Section off the sodal secret societies, Revolution-era leaders of the Asalewan Section, including Adelaja Ifedapo and Edudzi Agyeman themselves, actively discussed aspects of quasi-stateless Highlander society, especially direct democratic village councils and communal ownership of land, as legacies of primitive communism that were worthy of defending from colonialism and of integrating into councilist modernity, if under very different and much more egalitarian terms than they actually existed as.

Edudzi Agyeman, Rectifying Dogmatist Errors in our Section, May 17, 1938.

Jancius termed this co-option of traditional cultures in service to a revolutionary modernist vision "Primitive Modernism," comparing the early Section to peasant millennarian and early working-class movements that extensively deployed quasi-religious rhetoric, pomp, and traditionalistic ritual but distinguishing the Section from these movements insofar as the Section was and is a much more modern and centralized revolutionary force that developed a much more coherent and complex ideology and social structure that broadly supported, rather than resisted, centralization and modernization; Jancius also discussed the Section's origins in the colonized intelligentsia and upper echelons of the colonized working-class that only later appealed to subaltern elements such as the colonized peasantry, rather than originating in the peasantry as these movements largely did.

Despite this co-option of certain traditional structures during the Revolution, most scholars, including Jancius and Legalle, have still identified the Asalewan Section and Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism as fundamentally modernist. This is because the Section's adoption of traditional practices decreased over time; for example, throughout the Revolution the Section gradually though not entirely replaced the sodal secret societies' highly ritualistic form of secrecy, in some ways more symbolic than real, with a cell-based form of organization inspired by other councilist guerrillas in highly repressive conditions, such as the Voyins and Miersan partisans. Jancius and Legalle especially argued that the Section's modernist nature particularly became apparent after the Revolution's victory, when the Section became far less dependent on the support of forces attached to traditional practices, such as Highlander chiefs and big men, and could thus survive their resistance to its centralizing and modernist ambitions. During the 1950s and 1960s, particularly during the Anti-Tribal Revolution of 1958-1963, this entailed dramatic measures including a continuation and intensification of colonial-era sedentarization programs as one step towards agricultural collectivization, standardization of Asase Lewa's five official languages along the lines of dialects spoken in urban or dense rural areas, the prohibition of certain traditional practices such as female genital mutilation, mandating villages pay high taxes to fund expensive industrial, infrastructure, and social campaigns, and the compulsory integration of many sodal secret societies into the Asalewan Section's mass organizations.

Despite such measures and radical attacks on Asalewan traditional society, including Highlander society, most scholars have still argued that the Asalewan Section still practiced limited co-option of traditional values and communities, which the Asalewan Section and Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists themselves continued to embrace in a limited form. In 1961, for example, Edudzi Agyeman argued that "our village councils, our sodalities, our communities—these will, once cleansed from tribalist and comprador-bourgeois filth, work with our mass organizations and our Section to create an unbreakable bond that will carry us into councilism and communism." These scholars have argued that this rhetoric still matched reality; for example, in his book Planners and Peasants, Legalle argued that many Asalewan high modernist worldmaking projects during this period, most of which involved organizing people into modernist, nationwide communal and collective associations or structures, were somewhat more successful than most high modernist projects because they established traditional structures as the building-block of such associations.

Legalle especially discussed the Asalewan state's co-option of age sets as the building blocks of communal villages and neighborhoods in which childrearing, education, housework, and all other social reproduction would be done communally outside the family unit; in areas in which age sets were a traditional social structure, the Asalewan state largely allocated and segregated communal housing and labor tasks according to traditional age sets. Moreover, Legalle noted that in regions in which age sets became the building block of commune life, communes' collectivization of social reproduction encountered far less resistance, and has been far more likely to be retained until the modern day, than in regions where this was not the case. While the co-option of age sets into communal life was the Asalewan Section and state's most notable co-option of traditional community structures, Legalle argued that this was a widespread phenomenon, particularly in modernizing campaigns and programs heavily modified or adopted (as communes were) after the Protective-Corrective Revolution, which embraced Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism but led to the ideology developing a focus, at least nominally, on local democracy, which Jancius termed "councilist subsidiarity."

As examples, Legalle discussed the integration of sodal secret societies into the Asalewan Section's mass organizations—complete with different mass organizations' local branches adopting rituals and symbols based on those of their sodal secret society—as well as the creation of "communal Workers' Councils" as the building block of the state in the 1969 Constitution, communal councils designed to closely correspond to the size and scale of traditional Highlander village councils. Legalle also disaagreed with Jancius in arguing that the Section itself's abandonment of traditional, sodal-esque was not as complete as Jancius argued. Whereas the Section did indeed rely on cell-based organization to ensure its secrecy during the Asalewan Revolution, Legelle discussed the ways in which local Section branches in the Highlands, continue to use things such as sodal-esque initiatory rites when onboarding new members, or members donning special masks and uniforms—a hallmark of the sodal socieites—during special rituals, especially International Workers' Day.

Feminism

[Analysis of patriarchal social structures, including patriarchal families, as inherently connected to property ownership and hiearchy more broadly]

Family abolition

Developmentalism

Pan-Bahianism

Edudzi Agyeman, What is the Bahian?, September 21, 1950.

With the historical origins of the Asalewan Section of the Workers' International, and by extension Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism, lying within the left-wing of the Pan-Bahian movement of the early twentieth century, and specifically the left-wing minority at the Pan-Bahian Congress of 1907, Pan-Bahianism has played an instrumental role in Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism and traditionally seen as one of the most distinguishing features of the ideology. Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists, argued that Bahia's political and economic emancipation depended upon Bahia's ability to form a single political community and state. Adelaja Ifedapo and Edudzi Agyeman actively pressed for a Pan-Bahian state's implementation, with both figures, and Asase Lewa as a whole, playing an instrumental role in the formation of the Congress of Bahian States in 1956 and being one of the founding states of the United Bahian Republic in 1960. Even after the United Bahian Republic's dissoluton, the Asalewan Section of the Workers' International and the Asalewan state have remained, at least theoretically, Pan-Bahian, with the ection seeking to forge political unity amongst the Bahian left and the Asalewan state extensively sponsoring left-wing Pan-Bahian political movements, violent or nonviolent, throughout the continent, and otherwise seeking to make greater moves towards Bahian political and economic unification, such as by forming the Bank of Bahia in 1988.

However, although the Asalewan Section and state historically emphasized unity amongst Pan-Bahian leftists and socialists above all else, especially during the run-up to and period of the United Bahian Republic, scholars of nationalism and Pan-Bahianism have identified Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism as differing substantially from most pan-nationalist ideologies, either Bahian socialists within Bahia itself or other pan-nationalist movements, such as Sattarists who supported the creation of Zorasan. Whereas most pan-nationalists, like nationalists in general, have sought to emphasize a common heritage amongst the national community—such as a common language, culture, or religion—Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists do no such thing, instead arguing that no aspect of the Bahian experience that binds Bahians together save for one: their oppression, colonization, and subjugation. In his seminal 1950 text What is the Bahian?, Edudzi Agyeman went so far as to argue that it was the very experience of subjugation, oppression, and violence that created and defined Bahianness, and that the oppression of Bahians—either through slavery and, later, severe labor exploitation in the Asterias, or through extraction of natural resources and severe labor exploitation in Bahia—constituted, alongside the exploitation of labor by capital, the basis of the capitalist world-system. Influenced by this text, some twenty-first century scholars and theorists, especially amongst the Bahian diaspora in the Asterias, have advanced the theory of Bahiopessimism, arguing that Bahian people's exclusion and oppression is the defining characteristic of modernity and are pessimistic about the prospect of Bahian liberation while modernity remains. These Bahiopessimists are also skeptical of efforts, such as the Asalewan Section's, to achieve Bahian liberation through proletarian internationalism and revolution.

However, Edudzi Agyeman himself, and Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists more broadly, rejected this conclusion. Instead, Edudzi argued that, in much the same way as the proletariat constituted the universal class, whose interests were identical to those of humanity as a whole because their emancipation as a class could not come without the emancipation of humanity as a whole through the establishment of a communist classless society, Bahians constituted the "universal nation" and the "universal race," whose interests as a nation and race were indistinguishable from the colonized, the proletariat, or humanity as a whole. Edudzi argued that this was the case because Bahians collectively lacked a particular cultural heritage, with all the particular sectional, non-universal interests that implies—with such heritage only being held by Bahian sub-groups (in the same way that the proletariat collectively had no particular interests even if subsections of the proletariat do), and even that heritage having been seriously eroded during the Toubacterie—and because Bahians were, by definition, inherently oppressed under the capitalist world-system, thus having no choice but to agitate against it, at all times and without qualifications.

Edudzi, and Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists more broadly, thus argued in favor of Pan-Bahianism not on the basis of a common cultural heritage, but as an extension of their proletarian internationalism; they believed that any Pan-Bahian state dominated by the Bahian proletariat would have no choice but to pursue universal and pure proletarian internationalism, even moreso than other socialist countries that, though following broadly proletarian internationalist foreign policies, might sometimes pursue the particular interests of their country's working-class and in that way betray the proletariat and humanity as a whole. With a socialist world government appearing to be only a distant, long-term goal, the Asalewan Section of the Workers' International agitated for a Pan-Bahian state as something that could be achieved in the short-term and have the same proletarian internationalist foreign policy of, and strike directly at the heart of the capitalist world-system in the same way as, a global socialist state. Many academics, such as Algirdas Jancius, have thus argued that Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism paradoxically advocates a sort of of "internationalist nationalism," seeking to construct a particular national community precisely because that community's interests would be indistinguishable from humanity as a whole.

However, many academics have also questioned the extent to which the modern-day Asalewan Section of the Workers' International, and Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists more broadly, adhere to "internationalist nationalism." These academics, including Jancius himself and the Estmerish scholar of Bahian politics Gary Carter, have argued that the Asaslewan Section and state has, in the wake of the United Bahian Republic's dissolution and the collapse of other socialist Bahian states more broadly, increasingly focused on advancing Asase Lewa's particular interests internationally while increasingly seeking to construct a common national identity domestically, such as by seeking to create a common lingua franca in the form of Asalewan and by increasingly valorizing aspects of Asase Lewa's traditional and pre-colonial culture, especially its folk art and folk culture. While Asase Lewa's foreign policy remains in many ways proletarian internationalist and Pan-Bahian, and while its nationbuilding efforts retain a distinctly anti-colonial and socialist character, such policies do not retain the specific emphasis on advancing only the interests of the universal Bahian and proletarian communities seen in the mid-century Asalewan Section of the Workers' International.

Perpetual-Cyclical Revolution

Comparisons to other ideologies

Bahian socialism

Because the Asalewan Section came to power, and Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism was developed, during the Red Surge, when other left-wing movements came to power throughout the Global South, including Bahia, comparative historians of ideas have most frequently analyzed the ideology in comparison to the Bahian socialist ideologies of other left-wing Bahian governments during this period, such as the governments of Vudzijena Nhema and Abner Oronge. Though the ideology does share some similarities with Bahian socialism, including a synthesis of Pan-Bahianism and socialism, a strong rejection of the comprador bourgeoisie, and, in power, a strong emphasis on economic development, the two ideologies differ in important ways.

Most notably, while Bahian socialists frequently rejected class struggle and Nemtsovism, the Asalewan Section regarded, and still regards, Nemtsovism and class struggle as central to its ideology. As such, while in power many Bahian socialist governments sought to accommodate themselves to indigenous aristocratic, national-bourgeois, and middle classes, maintaining a mixed economy under a developmentalist framework, the Asalewan government did no such thing, waging thorough class struggle that resulted in the near-total nationalization and collectivization of the economy by the late 1950s.

Furthermore, while many Bahian socialists justified their policies as a return to the Sâretic system, the Asalewan Section, though admiring Sâre as a form of primitive communism, draws very little inspiration from any pre-colonial Bahian social systems. Rather than seeing its socialist project as a return to Sâre—whose vulnerability to Irfanic conquests the Section considered a sign of inherent weakness—the Asalewan Section's goal was, and remains, establishing a thoroughly modern council republic modelled after the modern, industrial powers of Valduvia and Chistovodia.

Councilism

Equalism

Sattarism

Though the two movements differ drastically ideologically, some commentators have noted distinct similarities between Sattarism and Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism. Both ideologies share origins in the anti-imperialist and anti-colonial movements of the early-to-mid twentieth century, and anti-imperialist rhetoric thus features prominently in both ideologies and their according political movements. Furthermore, both ideologies view greater South-South cooperation, and more narrowly political unification of their respective regions, as necessary to combat Euclean imperialism, with Sattarists advocating Pan-Zorasanism and Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzists advocating Pan-Bahianism.

In addition to this shared anti-imperialist history, comparative scholars of ideas have also identified both ideologies as strongly collectivist and militarist in character, with the Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzist emphasis on Communalization mirroring the Sattarist emphasis on Ettehâd. In addition to an extensive emphasis on unity in both Asalewan and Zorasani propgadanda and thought, both countries have adopted similar measures at encouraging such unity. While in power, both the Asalewan Section and the Revloutionary Masses Party and National Renovation Front created mass organizations attached to themselves and whose membership comprises a substantial portion of the population, with as the Asalewan Revloutionary Councilist Defence Committees, Junior Workers' League, and All-Asase Lewa Women's Federation mirroring the Zorasani Sar-Parast Aghtar, Young Companions of the Union, and National Renovation Front#Women and Mothers of the Union.

Both the Asaleawn Section and National Renovation Front also regularly stage government-organized demonstrations, in the Asalewan case ideologically justified through the "Perpetual" aspect of Perpetual-Cyclical Revolution and in the Zorasani case justified through the doctrine of Perpetual Mass Mobilization. Mirroring these mass organizations and mobilizations is both the Asalewan Section and National Renovation Front's close links with each country's respective militaries and an emphasis on the mass militarization of society, militarization aimed both at strengthening national security and at further fostering nationalistic and collectivistic sentiment in the people.

However, scholars have also identified key differences between Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism and Sattarism, and more broadly the ruling styles of the Asalewan Section and the Revolutionary Masses Party and National Renovation Front. Most prominent among these differences is the ideologies' differing economic views, as Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism emphasizes class struggle and stridently rejects all forms of private property whereas Sattarism emphasizes class collaboration accepts a limited form of private property, in the Neo-Sattarist case accepting a central role for private property and capitalist markets in the economy. Similarly, Nemtsovism-Tretyakism-Adelajism-Edudzism's materialist and scientific socialist rejection of religion contrasts with Sattarism's adoption of Political Irfan.

Furthermore, many scholars have also argued that the mass-mobilizing and collectivist aspects of Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzist and Sattarist ideology, while superficially similar, differ substantially in practice, particularly since the Protective-Corrective Revolution. While, under the Sattarist logic of Ettehâd, mass organizations simply advanced the classical totalitarian role of allowing the party-state to control and mobilize the population, these scholars argue that in the Nemtsovist-Tretyakist-Adelajist-Edudzist case, mass organizations are conceptualized as, and have indeed served, a dual role, simultaneously expanding the party-state's control and politically empowering the masses as part of a dialectic between the masses and the political vanguard in which the masses are ultimately supreme.

These scholars especially contrast the roles of the Asalewan Women's Federation and League of Labor with their Zorasani counterparts; while their Zorasani counterparts are almost entirely controlled by the state, in the Asalewan case these organizations, or their sub-groups, are semi-autonomous have waged political campaigns in their own right, sometimes coming into conflict with the Section center. Furthermore, since the Protective-Corrective Revolution the Asalewan Section has, in lieu of directly administering the country, instead shared power with the elected governments as part of the broader Asalewan model of "Illiberal Councilism," further contrasting with the Sattarist notion of the party directly controlling the state.