Music of Garambura: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (10 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

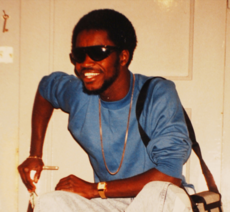

[[File:Cheikh_Lo_Way_Out_West_2013_(cropped).jpg|230px|thumb|right|{{wp|Cheikh Lo|Karam Hy}}, one of Garambura's most internationally renowned musicians, at the ''Fête de la lumière'', [[Ouagedji]], [[Mabifia]], in 2015.]] | |||

The '''music of Garambura''' has, over its years of development and history, come to encompass a wide range of genres, styles, motifs and art forms while utilising a myriad of cultural influences, both domestically and from abroad. Garambura has [[Bahia]]'s largest {{wp|music industry}} and {{wp|sound recording|sound recording industry}} by market capital, and is home to some of Bahia's most illustrious {{wp|music festivals}} and {{wp|studios}}. Major Bahian labels such as {{wp|Nyege Nyege|Sebaka}} and {{wp|Gallo Record Company|Courtet{{ndash}}Yucunou Company}} are headquartered in [[Mambiza]], a city renowned for its musical diversity. | The '''music of Garambura''' has, over its years of development and history, come to encompass a wide range of genres, styles, motifs and art forms while utilising a myriad of cultural influences, both domestically and from abroad. Garambura has [[Bahia]]'s largest {{wp|music industry}} and {{wp|sound recording|sound recording industry}} by market capital, and is home to some of Bahia's most illustrious {{wp|music festivals}} and {{wp|studios}}. Major Bahian labels such as {{wp|Nyege Nyege|Sebaka}} and {{wp|Gallo Record Company|Courtet{{ndash}}Yucunou Company}} are headquartered in [[Mambiza]], a city renowned for its musical diversity. | ||

Garamburan music can be categorised in a number of genres, including {{wp|electronic music|electronic}}, {{wp|folk music|folk}}, {{wp|hip hop}}, {{wp|jazz}}, {{wp|pop}}, {{wp|R&B}}, {{wp|rock music|rock}} and {{wp|soul}}, as well as hundreds of subgenres that encaptulate the country's cultural diversity. Many native genres, such as {{wp|coupé-décalé}}, {{wp|Tradi-Modern| | Garamburan music can be categorised in a number of genres, including {{wp|electronic music|electronic}}, {{wp|folk music|folk}}, {{wp|hip hop}}, {{wp|jazz}}, {{wp|pop}}, {{wp|R&B}}, {{wp|rock music|rock}} and {{wp|soul}}, as well as hundreds of subgenres that encaptulate the country's cultural diversity. Many native genres, such as {{wp|coupé-décalé}}, {{wp|Tradi-Modern|Gondaphoniques}}, {{wp|gqomme}}, {{wp|kizoumba}}, {{wp|kouaito}}, {{wp|makossa}}, {{wp|mbaqanga}}, {{wp|ndombolou}}, {{wp|african blues|Gnicaitsva blues}} and {{wp|semba}} take significant influence from native musical traditions, often incorporating {{wp|western music|northern musical influences}} into traditional {{wp|African music|Bahian ritualistic music}}. | ||

Culturally, music from Garambura has had a significant impact on music in Bahia as well as other global music genres. {{wp|Afrobeat|Baiabeat}} was partially pioneered in [[Mambiza]], and is now popular across [[Euclea]] and the [[Asterias]]. Diasporic music is popular across the [[Euclean Community]], particularly in [[Gaullica]]. Large cultural exchanges have taken place between the countries, influenced by both native and [[Chennois]] populations. Garambura has participated in the [[Euclovision Song Contest]] since 1999. | Culturally, music from Garambura has had a significant impact on music in Bahia as well as other global music genres. {{wp|Afrobeat|Baiabeat}} was partially pioneered in [[Mambiza]], and is now popular across [[Euclea]] and the [[Asterias]]. Diasporic music is popular across the [[Euclean Community]], particularly in [[Gaullica]]. [[Garambura-Gaullica relations#Music|Large cultural exchanges have taken place between the countries]], influenced by both native and [[Chennois]] populations. Garambura has participated in the [[Euclovision Song Contest]] since 1999. | ||

== Traditional music == | == Traditional music == | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

== Modern music == | == Modern music == | ||

=== Electronic, house, dance === | === Electronic, house, dance === | ||

==== Coupé-décalé and | ==== Coupé-décalé and ndombolou ==== | ||

{{wp|Coupé-décalé}} is a genre of Garamburan house music that first emerged in [[Mambiza]] in the mid-2000s. Inspired sonically by earlier house developments in the 1980s and 1990s, coupé-décalé separated itself from other genres due to its heavy cultural adoption of {{wp|Hip-hop#Culture|hip-hop culture}}, reminiscent of similar cultures that had developed in [[Euclea]] and the [[Asterias]] prior. | {{wp|Coupé-décalé}} is a genre of Garamburan house music that first emerged in [[Mambiza]] in the mid-2000s. Inspired sonically by earlier house developments in the 1980s and 1990s, coupé-décalé separated itself from other genres due to its heavy cultural adoption of {{wp|Hip-hop#Culture|hip-hop culture}}, reminiscent of similar cultures that had developed in [[Euclea]] and the [[Asterias]] prior. | ||

Stylistically, coupé-décalé is characterised by modern instrumentation (such as {{wp|drum machines}} or {{wp|sampling}}) moulded around traditional Bahian {{wp|percussion}} and {{wp|rhythm}}. The genre's popularity exploded with the release of {{wp|Douk Saga|Mosegi Gomolemo}}'s ''Sagacité'' in 2004. Some instances of the music also take some influence from {{wp|dub}} and {{wp|reggae}}, though these are less pronounced. | Stylistically, coupé-décalé is characterised by modern instrumentation (such as {{wp|drum machines}} or {{wp|sampling}}) moulded around traditional Bahian {{wp|percussion}} and {{wp|rhythm}}. The genre's popularity exploded with the release of {{wp|Douk Saga|Mosegi Gomolemo}}'s ''Sagacité'' in 2004. Some instances of the music also take some influence from {{wp|dub}} and {{wp|reggae}}, though these are less pronounced. | ||

{{wp| | {{wp|ndombolou}} developed around the same time as coupé-décalé, though its origins stem from {{wp|soukous}} and other fast-paced music. Today, it is generally considered as the "mainstream" of Garamburan dance music, with many Garamburan ndombolou artists garnering success across Bahia. ndombolou has also began to attract diasporic musicians in Euclea to its style, as well as the adoption of its dance styles. | ||

==== | ==== Gondaphoniques ==== | ||

Gondaphoniques refers to the brash, {{wp|electro-industrial}} sounds that developed along the [[Gonda|Gonda delta]] in the mid-2000s. Also referred to as ''tradi-modern'', alluding to its descent from traditional Bahian {{wp|trance music}}, it developed its notoriety for its loud public concerts throughout the city of [[Mambiza]], where the dense urban landscape amplifies the sound throughout the streets. [[Satucin|Satucine]] music critic Caroline Crépin compared these concerts to {{wp|busking}} in the western world, though it differs notably in key aspects. Gondaphoniques concerts are often conducted free of charge, and spectators are not expected to donate as they would be in the north when watching buskers. | |||

[[File:KononoN°1.jpg|200px|right|thumb|{{wp|Konono No.1|Ukuvuselelwa kweNtlalo}} performing in [[Nambabi]], [[Maucha]] in 2009.]] | [[File:KononoN°1.jpg|200px|right|thumb|{{wp|Konono No.1|Ukuvuselelwa kweNtlalo}} performing in [[Nambabi]], [[Maucha]] in 2009.]] | ||

{{wp|Konono No.1|Ukuvuselelwa kweNtlalo}} are often considered as pioneers of the genre. It gained a wider international following when their song ''Ntawha'' was [[Garambura]]'s submission to the [[Euclovision Song Contest|2005 Euclovision Song Contest]] held in [[Patovatra]], [[Soravia]]. | {{wp|Konono No.1|Ukuvuselelwa kweNtlalo}} are often considered as pioneers of the genre. It gained a wider international following when their song ''Ntawha'' was [[Garambura]]'s submission to the [[Euclovision Song Contest|2005 Euclovision Song Contest]] held in [[Patovatra]], [[Soravia]]. | ||

As with many other Garamburan genres, | As with many other Garamburan genres, Gondaphoniques often take on a communal aspect. Often used as music for get-togethers, special events such as birthdays or weddings as well as larger local and communal events, the music has come to symbolise the dense urban culture of [[Mambiza]], where it originates. Many instruments are used in Gondaphoniques, and can range from simple {{wp|drum|street drums}} such as {{wp|pots and pans}} to [[Sainte-Chloé|Chloesian]] {{wp|steelpan|steelpans}}, {{wp|guitars}} and other {{wp|percussion instruments}}. Chanting vocals also form an integral part of Gondaphoniques, often encouraging crowd participation. | ||

==== | ==== gqomme ==== | ||

{{wp|gqomme}} was a style of dance music that emerged predominantly among the {{wp|Tswa people|Kenema}} and {{wp|Swazi people|Nkalu peoples}} in central Garambura (mainly [[Tawira]] and [[Kugura]]) in the early 2010s. Though its name comes from the Kulo language, coined by Kulo journalist Dinale Izigala in 2011, it enjoys almost no popularity on the southern coast, which is dominated mainly by {{wp|coupé-décalé}} and {{wp|ndombolou}}. gqomme is often compared to {{wp|ambient house}}, {{wp|microhouse}} and {{wp|outsider house}}. Its niche sound has allowed it to remain a nationally underground genre, with significant regional scenes. gqomme is characterised by its quiet, minimal beats, often having uncharacteristic tempos and utilising {{wp|synthesisers}} both in and on top of the beat. | |||

Nightclubs and another similar venues are where gqomme enjoys its popularity. | |||

=== Hip hop === | === Hip hop === | ||

| Line 42: | Line 41: | ||

However, by far the most popular method is that artists born in Garambura or with Garamburan ancestry gain popularity abroad, later returning to Garambura to play shows or to generally increase contact with the country. In a similar vein to popular jazz musicians of the early 20th century, many hip hop artists, especially those with roots in {{wp|conscious hip hop}}, and whose themes have included race, return to the country. | However, by far the most popular method is that artists born in Garambura or with Garamburan ancestry gain popularity abroad, later returning to Garambura to play shows or to generally increase contact with the country. In a similar vein to popular jazz musicians of the early 20th century, many hip hop artists, especially those with roots in {{wp|conscious hip hop}}, and whose themes have included race, return to the country. | ||

The popularity of {{wp|disc jockey|DJs}} and {{wp|house music}} in Garambura did lead to the emergence of {{wp| | The popularity of {{wp|disc jockey|DJs}} and {{wp|house music}} in Garambura did lead to the emergence of {{wp|kouaito}} in [[Mambiza]] in the late 1980s. It also has roots in {{wp|dancehall}} and, predominantly, {{wp|hip hop}}. kouaito is the largest domestic genre that could be considered an extension of hip hop. | ||

=== Jazz === | === Jazz === | ||

| Line 101: | Line 100: | ||

=== R&B and soul === | === R&B and soul === | ||

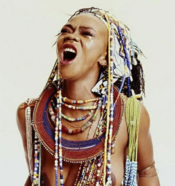

[[File:Nneka_@_cargo,_london_(cropped).jpg|right|220px|thumb|{{wp|Nneka (singer)|Maphit}} is Garambura's most famous modern R&B/soul artist.]] | |||

{{wp|Rhythm and blues}} is a genre that was pioneered by Astero-Bahian communities in the mid-20th century, but it was not until the 1970s with the loosening of radio that R&B was able to reach Garambura in any sizable measure. With stylistic origins rooted firmly in {{wp|jazz}}, Garamburan R&B easily and quickly blossomed into a unique regional scene, adopting the influences of littoral jazz instrumentalists such as {{wp|Theolonius Monk|Alessane Assise}} as well as traditional Bahian instruments like large {{wp|drums}} and sometimes {{wp|choir|choral elements}}. R&B was one of the first genres to gain popularity after Garamburan independence in 1969, and in the early 1970s it was the Courtet-Yucunou Company's largest genre. | |||

After a decline in the 1980s and 1990s, Asterian artists began to visit and play shows in [[Mambiza]], at the time one of the world's fastest-growing cities and economies, which stipulated a domestic revival of R&B. These artists, referred to as the "second wave", took much heavier influence from their Asterian counterparts, mostly ditching Bahian instrumentation and tempo in favour of a more Euclean-influenced sound. It was around this period that {{wp|soul}}, which had emerged in the Asterias as a blend of [[Sotirianity|Sotirian]] {{wp|gospel music}} and R&B, found its popularity in Garambura. In reality, these two genres overlapped a lot, but soul found a growing demographic of artists who took great inspiration from {{wp|rock music}} such as Gnicaitsva blues, giving some Garamburan soul a psychedelic sound. | |||

Today, R&B and soul often blend with hip-hop in popular music, with the audience for the genres on their own steadily diminishing. Despite this, some smaller artists have worked to revive the traditional Garamburan psychdelic soul sound, including Magdelene Gappah, {{wp|Genesis Owusu|Tumai Guti}} and Tomtenda Carné. | |||

=== Rock music === | === Rock music === | ||

==== | ==== Gnicaitsva blues ==== | ||

[[File:MediaPlayer.png|200px|link=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nhqk3bHmnk0|thumb|right|{{wp|Mdou Moctar|Kaswatu Kabili}}'s ''{{wp|Mdou Moctar|Tarhatazed}}'', released in 2008, is a seminal piece of | [[File:MediaPlayer.png|200px|link=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nhqk3bHmnk0|thumb|right|{{wp|Mdou Moctar|Kaswatu Kabili}}'s ''{{wp|Mdou Moctar|Tarhatazed}}'', released in 2008, is a seminal piece of Gnicaitsva blues.]] | ||

Gnicaitsva blues takes its name from the mountain range close to where its stylistic background originates. Gnicaitsva blues refers to a select style of {{wp|blues music}} originating from rural communities that live near the mountains or in the north of the country. It is often characterised by smooth, slick guitar and droning, repetitive and often psychedelic vocals. Gnicaitsva blues share incredible similar origins and sounds to {{wp|Tishoumaren|Boual blues}}, native to the peoples of the [[Boual ka Bifie]] in [[Mabifia]] and [[Yemet]]. | |||

The genre's birth was in the 1980s, and initially it was popular amongst {{wp|Khoikhoi|Shuku}} and {{wp|Chewa|Njinji}} peoples, who adopted it into their own musical traditions. Due to linguistic and cultural isolation, Shuku | The genre's birth was in the 1980s, and initially it was popular amongst {{wp|Khoikhoi|Shuku}} and {{wp|Chewa|Njinji}} peoples, who adopted it into their own musical traditions. Due to linguistic and cultural isolation, Shuku Gnicaitsva is often critically considered to be the purest form of Gnicaitsva blues, having remained relatively untouched by northern and domestic musical trends. Chewa Gnicaitsva is by far the most commercially successful variant, having experienced a cultural boom in the mid-2000s as [[Euclea|Euclean]] and [[Asterias|Asterian]] producers oversaw the creation and promotion of some of Gnicaitsva's most well-known artists, including {{wp|Mdou Moctar|Kaswatu Kabili}} and {{wp|Bombino|Komaniso}}. Kabili's use of {{wp|autotune}} on the {{wp|electric guitar}} is often viewed as revolutionary for the genre. | ||

[[File:Turnstile_Band.jpg|200px|left|thumb|{{wp|Turnstile|Tourniquet}}, Garambura's most commercially successful punk band.]] | [[File:Turnstile_Band.jpg|200px|left|thumb|{{wp|Turnstile|Tourniquet}}, Garambura's most commercially successful punk band.]] | ||

==== Punk rock ==== | ==== Punk rock ==== | ||

| Line 172: | Line 177: | ||

|'''[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dkr3ca42u_U Amidinine]''' | |'''[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dkr3ca42u_U Amidinine]''' | ||

|'''{{wp|Bombino|Komaniso}}''' | |'''{{wp|Bombino|Komaniso}}''' | ||

|168 | |'''168''' | ||

|1st | |'''1st''' | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Euclovision Song Contest|2007]] | |[[Euclovision Song Contest|2007]] | ||

| Line 264: | Line 269: | ||

|57 | |57 | ||

|22nd | |22nd | ||

|- | |||

|[[Euclovision Song Contest 2022|2022]] | |||

|[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tvY31eN3gtE Viser et tuer?] | |||

|{{wp|Little Simz|Olivia Le Sueur}} | |||

|59 | |||

|12th | |||

|- | |||

|[[Euclovision Song Contest 2023|2023]] | |||

|[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yC91GYRqwH0 Rima Rima] | |||

|{{wp|Tshegue|Marie Marachera}} | |||

|63 | |||

|14th | |||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

Latest revision as of 16:04, 1 January 2024

The music of Garambura has, over its years of development and history, come to encompass a wide range of genres, styles, motifs and art forms while utilising a myriad of cultural influences, both domestically and from abroad. Garambura has Bahia's largest music industry and sound recording industry by market capital, and is home to some of Bahia's most illustrious music festivals and studios. Major Bahian labels such as Sebaka and Courtet–Yucunou Company are headquartered in Mambiza, a city renowned for its musical diversity.

Garamburan music can be categorised in a number of genres, including electronic, folk, hip hop, jazz, pop, R&B, rock and soul, as well as hundreds of subgenres that encaptulate the country's cultural diversity. Many native genres, such as coupé-décalé, Gondaphoniques, gqomme, kizoumba, kouaito, makossa, mbaqanga, ndombolou, Gnicaitsva blues and semba take significant influence from native musical traditions, often incorporating northern musical influences into traditional Bahian ritualistic music.

Culturally, music from Garambura has had a significant impact on music in Bahia as well as other global music genres. Baiabeat was partially pioneered in Mambiza, and is now popular across Euclea and the Asterias. Diasporic music is popular across the Euclean Community, particularly in Gaullica. Large cultural exchanges have taken place between the countries, influenced by both native and Chennois populations. Garambura has participated in the Euclovision Song Contest since 1999.

Traditional music

Music has formed the backbone of many Garamburan communities for hundreds of years. Drums and flutes are commonly found among pre-colonial musical artefacts. Musicologists have theorised that the stylistic origins of Garamburan music before contact with Euclea comes from various different places, including Rahelia, Mabifia and even as far south as Dezevau. The cithara, which had been popularised in northern Rahelia from the Piraean states of antiquity, spread to Garambura through trade routes through the Ténéré desert, beginning centuries of guitar development completely separate to mainland Euclea. The salpinx was another instrument whose origins come from ancient Piraea, eventually becoming the Hondrine, whose sharp, shrill tones allowed many Garamburan peoples to warn villages of River Bedouin raids.

Choirs and choral traditions made their way into Garambura from Dezevau. It was popular especially amongst the Nwaia and Okatuo peoples, whose use of vocals completely eclipsed instrumentalism. Both groups developed their own separate styles of throat singing that is similar in complexion to vocalists of central Coius. The Nwaia refer to this as tandavhudza whilst the Okatuo term, more common in general use, is mukolwe (often rendered as moukoloué).

Drums such as the karyenda and ngoma played a large part in music across pre-colonial Garambura. The use of percussion was a common trait amongst nearly all tribes, and their purpose varied immensely. Drums were most often used to crown karames during the Houregic period, with larger drums often correlating to a show of respect and a display of power on the karame's behalf. Drumming was more often than not high-tempo, ranging from andante (76–108 bpm), common in more macabre settings such as funerals, to allegro (120–156 bpm), which was more common and used for a myriad of events such as coronations, weddings, communal gatherings as well as intimidation. The Sisulu people regularly used drums as means of intimidation as well as tactically. Etruro-Zorasani historian Ahmed Cassemi wrote that the Sisulu often used dense woodland to their advantage. The echo and reverberate effect produced by the trees was used to amplify the presence of the Sisulu armies before battle. Its used was famously documented before Mabhuti's raid on Sainte-Germaine in 1772, where the city was plundered by Sisulu armies.

Modern music

Electronic, house, dance

Coupé-décalé and ndombolou

Coupé-décalé is a genre of Garamburan house music that first emerged in Mambiza in the mid-2000s. Inspired sonically by earlier house developments in the 1980s and 1990s, coupé-décalé separated itself from other genres due to its heavy cultural adoption of hip-hop culture, reminiscent of similar cultures that had developed in Euclea and the Asterias prior.

Stylistically, coupé-décalé is characterised by modern instrumentation (such as drum machines or sampling) moulded around traditional Bahian percussion and rhythm. The genre's popularity exploded with the release of Mosegi Gomolemo's Sagacité in 2004. Some instances of the music also take some influence from dub and reggae, though these are less pronounced.

ndombolou developed around the same time as coupé-décalé, though its origins stem from soukous and other fast-paced music. Today, it is generally considered as the "mainstream" of Garamburan dance music, with many Garamburan ndombolou artists garnering success across Bahia. ndombolou has also began to attract diasporic musicians in Euclea to its style, as well as the adoption of its dance styles.

Gondaphoniques

Gondaphoniques refers to the brash, electro-industrial sounds that developed along the Gonda delta in the mid-2000s. Also referred to as tradi-modern, alluding to its descent from traditional Bahian trance music, it developed its notoriety for its loud public concerts throughout the city of Mambiza, where the dense urban landscape amplifies the sound throughout the streets. Satucine music critic Caroline Crépin compared these concerts to busking in the western world, though it differs notably in key aspects. Gondaphoniques concerts are often conducted free of charge, and spectators are not expected to donate as they would be in the north when watching buskers.

Ukuvuselelwa kweNtlalo are often considered as pioneers of the genre. It gained a wider international following when their song Ntawha was Garambura's submission to the 2005 Euclovision Song Contest held in Patovatra, Soravia.

As with many other Garamburan genres, Gondaphoniques often take on a communal aspect. Often used as music for get-togethers, special events such as birthdays or weddings as well as larger local and communal events, the music has come to symbolise the dense urban culture of Mambiza, where it originates. Many instruments are used in Gondaphoniques, and can range from simple street drums such as pots and pans to Chloesian steelpans, guitars and other percussion instruments. Chanting vocals also form an integral part of Gondaphoniques, often encouraging crowd participation.

gqomme

gqomme was a style of dance music that emerged predominantly among the Kenema and Nkalu peoples in central Garambura (mainly Tawira and Kugura) in the early 2010s. Though its name comes from the Kulo language, coined by Kulo journalist Dinale Izigala in 2011, it enjoys almost no popularity on the southern coast, which is dominated mainly by coupé-décalé and ndombolou. gqomme is often compared to ambient house, microhouse and outsider house. Its niche sound has allowed it to remain a nationally underground genre, with significant regional scenes. gqomme is characterised by its quiet, minimal beats, often having uncharacteristic tempos and utilising synthesisers both in and on top of the beat.

Nightclubs and another similar venues are where gqomme enjoys its popularity.

Hip hop

Hip hop in Garambura has undergone varying periods of influence and popularity since the 1990s. Most of the genre's consumption in the country comes from its extensive popularity amongst Bahian diasporic countries in Euclea and the Asterias. Some of that influence led to brief spats of domestic hip hop trends where Garamburan artists became popular domestically.

However, by far the most popular method is that artists born in Garambura or with Garamburan ancestry gain popularity abroad, later returning to Garambura to play shows or to generally increase contact with the country. In a similar vein to popular jazz musicians of the early 20th century, many hip hop artists, especially those with roots in conscious hip hop, and whose themes have included race, return to the country.

The popularity of DJs and house music in Garambura did lead to the emergence of kouaito in Mambiza in the late 1980s. It also has roots in dancehall and, predominantly, hip hop. kouaito is the largest domestic genre that could be considered an extension of hip hop.

Jazz

Littoral jazz

Littoral jazz is the name given to the variant of jazz music that emerged from the sœurs littorales (Mambiza and Makumba) in the 1910s and 1920s, spurred on by colonial authorities' promotion of Euclean music, styles and instrumentation. Unlike other jazz forms of the era, littoral jazz drew heavy inspiration from traditional percussion, including the balafon and karyenda, mixed in with traditional Euclean instruments such as the saxophone, trumpet and piano, all of which blended together a cohesive fusion genre.

Early forms of the genre were popular amongst Chennois demographics, whom jazz was usually targeted towards, but littoral jazz began to take form as a true cultural movement amongst the predominantly black audience of shebeens, where native instruments were much more commonplace. Many shebeens formed the basis of small cultural and tribal communities, and as such ritualistic themes were often incorporated into littoral jazz. In its early days, littoral jazz was a community-driven art form. Emerging before the commercialisation of music, performers were often based within local towns, and rarely travelled. The genre was extremely diverse, and styles varied from village to village, with styles often co-existing in the same areas.

When music began to be sold as a commodity in Baséland around the mid-1920s, littoral jazz was the first genre to gain a sizable commercial fanbase. Under functionalist administration, native music was forbidden from having a decent commercial framework, so littoral jazz took much of its influence under its broad umbrella to be marketed to commercial consumers.

After the decolonisation of Bahia, littoral jazz retained its stature of being Garambura's most popular musical export. In Rwizikuru it found a new audience in Freemen, but grassroots jazz movements still remained and formed the backbone of many communities. Once the ban on native music was lifted by the Rwizikuran government, littoral jazz took on a much more experimental approach. At the forefront of this change was Alessane Assise, who utilised his natural proficiency on the piano as well as an expansive backing band comprised of drummers, vocalists and other percussionists to create the first modern works of littoral jazz.

Motsamao

Motsamao is a type of dance music that emerged from Mambiza in the 1970s, incorporating heavy inspiration from littoral jazz as well as the emergence of modern instrumentation such as electric guitars. The word motsamao comes from Eastern Molisa for "movement", and was popularised by the Molisa diaspora in the city. It is also known as zvekare nezvitsva ("old and new"; veRwizi), umdaniso wasemantla ("northern dance"; Sisulu) and rarely as chanson garambourenne ("Garamburan chanson"; Gaullican).

Motsamao is particularly popular at nightclubs and bars, and is also a popular genre to be played live.

Mbaqanga

Mbaqanga is a type of music that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, but was refined in the late 1970s and ultimately emerged in its most popular form in the 1980s.

The genre stems from the localised choirs in the towns that lay on the urban boundaries of Mambiza. Prior to the mainstream introduction of music labels in Garambura, this music had difficulty gaining any traction outside of their localised communities. In addition to this, the hostility of the Rwizikuran government to independent music further stifled early mbaqanga. With Garamburan independence in 1979, northern music culture rapidly entered Garambura, uprooting and fusing with pre-existing native genres. Mbaqanga was majorly influenced by disco music and pop music, before emerging in the mainstream with the bustling trio "Amakhosazana" de la Lune. In addition to this, some northern musicians latched onto the popularity and influences of mbaqanga, incorporating it into their own music and further contributing to its international popularity.

Pop

Popular music in Garambura was first imported into the country in the 1960s and has since taken on a diverse array of musical influences, most of which stem from northern pop music and the trends associated with it. Pop music in Garambura is often likened to its northern counterparts, however in recent times the genre has taken on significantly more native influence, both instrumental and vocal, to create a geographically unique pop music scene similar to many other nations in Bahia.

Yé-yé was one of the first mainstream pop derivatives that took root in Garambura. Stemming from traditional Gaullican chanson, its sunny upbeat style contrasted greatly with the social, political and economic outlooks of the time. As Jean-Guy Auberjonois says:

Yé-yé was not only a...musical movement in the old world. But much so, even if indirectly, an escape from the real world in the new. Its rise coincides with political turmoil in many countries, and often times in a period of near-national emotional slumps, music provided a glimmer of hope. It really attests to the power of song and the popularity of the music around the world.

The genre is generally considered to have been popularised by Kesselbourgish singer Annalore Lemmens, whose song Een dag in het leven became a global hit when it won the inaugural 1959 Euclovision Song Contest in her home country. Through Gaullica, the song eventually came to be played on Garamburan radio stations, even through the 1960s and 1970s. Both the song and the genre's popularity provided pop music in Garambura with a suitable platform to grow, and many Garamburan yé-yé singers went on and found popularity in Gaullica and elsewhere in the Gaullophone world. It developed hand-in-hand alongside littoral jazz.

The 1970s and 1980s saw the rise of djeli pop, a Bahian subgenre of popular music that briefly swept the globe. After the gradual fall of djeli pop, northern influences began to dominate Garamburan pop once again. The rise of synthpop in the 1980s saw a similar rise in Garambura in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Unlike other genres of music, pop's relatively vague and free-flowing style allowed an easier incorporation of native cultural influences, with migration from elsewhere having an impact on localised styles. Examples include Lunaire, a singer whose emphasis on harmonic chorals in her music stems from her gowsa heritage and Dezevauni music culture as a whole. Similarly, Brundoré, whose ancestry hails from Sainte-Chloé often uses traditional Arucian instruments such as steelpans in her music.

Djeli pop

Djeli pop was a significant musical and cultural movement that swept across Bahia in the 1970s and 1980s. In Garambura, this cultural facet is exacerbated due to djeli pop often taking up the role of music partaining to the Garamburan War of Independence and the subsequent early years of independence. Many influential djeli pop artists from Garambura had relatives who served in the war, which made the music significant for many people.

Stylistically, djeli pop takes heavily from a blend of traditional musical lifestyles of the Boual ka Bifie peoples blended with heavy northern influences, including rock music, disco and early Euclopop, later also incorporating punk rock into its repertoire. Early djeli pop had very mellow influences, and in the case of its first star, Mabifian Honorine Uwineza, idolising traditional lifestyles during the regime of Fuad Onika. Under the wing of Chloe Kolisi, djeli pop took a turn towards punk rock, becoming a symbol of protest, upheaval and political expression, especially among Euclea's diasporic Bahian population.

Through djeli pop's roots and development in Garambura, it quickly split into multiple different styles and genres. By this point, Kolisi was a global name, having projected her style of music across the world. After an appearance on the cover of Rythme, the punk-influenced new style of djeli pop had become the global mainstream. Simultaneously, lesser known artists in Garambura were sticking to the traditional aspects of the genre with a modern twist. With renewed Euclopop and Euclo-disco influences, Mambiza-based quarter L'Exilé catapulted themselves into the djeli pop mainstream again, with their music proving popular in clubs across the country and eventually across the world.

R&B and soul

Rhythm and blues is a genre that was pioneered by Astero-Bahian communities in the mid-20th century, but it was not until the 1970s with the loosening of radio that R&B was able to reach Garambura in any sizable measure. With stylistic origins rooted firmly in jazz, Garamburan R&B easily and quickly blossomed into a unique regional scene, adopting the influences of littoral jazz instrumentalists such as Alessane Assise as well as traditional Bahian instruments like large drums and sometimes choral elements. R&B was one of the first genres to gain popularity after Garamburan independence in 1969, and in the early 1970s it was the Courtet-Yucunou Company's largest genre.

After a decline in the 1980s and 1990s, Asterian artists began to visit and play shows in Mambiza, at the time one of the world's fastest-growing cities and economies, which stipulated a domestic revival of R&B. These artists, referred to as the "second wave", took much heavier influence from their Asterian counterparts, mostly ditching Bahian instrumentation and tempo in favour of a more Euclean-influenced sound. It was around this period that soul, which had emerged in the Asterias as a blend of Sotirian gospel music and R&B, found its popularity in Garambura. In reality, these two genres overlapped a lot, but soul found a growing demographic of artists who took great inspiration from rock music such as Gnicaitsva blues, giving some Garamburan soul a psychedelic sound.

Today, R&B and soul often blend with hip-hop in popular music, with the audience for the genres on their own steadily diminishing. Despite this, some smaller artists have worked to revive the traditional Garamburan psychdelic soul sound, including Magdelene Gappah, Tumai Guti and Tomtenda Carné.

Rock music

Gnicaitsva blues

Gnicaitsva blues takes its name from the mountain range close to where its stylistic background originates. Gnicaitsva blues refers to a select style of blues music originating from rural communities that live near the mountains or in the north of the country. It is often characterised by smooth, slick guitar and droning, repetitive and often psychedelic vocals. Gnicaitsva blues share incredible similar origins and sounds to Boual blues, native to the peoples of the Boual ka Bifie in Mabifia and Yemet.

The genre's birth was in the 1980s, and initially it was popular amongst Shuku and Njinji peoples, who adopted it into their own musical traditions. Due to linguistic and cultural isolation, Shuku Gnicaitsva is often critically considered to be the purest form of Gnicaitsva blues, having remained relatively untouched by northern and domestic musical trends. Chewa Gnicaitsva is by far the most commercially successful variant, having experienced a cultural boom in the mid-2000s as Euclean and Asterian producers oversaw the creation and promotion of some of Gnicaitsva's most well-known artists, including Kaswatu Kabili and Komaniso. Kabili's use of autotune on the electric guitar is often viewed as revolutionary for the genre.

Punk rock

When punk rock began to become popular in Estmere and Gaullica, the first punk rock bands began to emerge amongst Chennois bands who regularly travelled between Gaullica and Garambura. Punkesque vocals had been pioneered independently by Chloe Kolisi and her spat of popularity as one of the faces of djeli pop in the 1970s, but punk as a genre was influenced almost entirely by its Euclean counterparts. As such, punk in Garambura has often been criticised for its disproportionately white makeup, a trend that has continued into the modern day.

Popular punk bands in Garambura include Izono, LMDTY and Tourniquet.

Euclovision Song Contest

Garambura has participated in the Euclovision Song Contest since its addition in 1999, winning once in 2006. Financial difficulties caused the ensuing contest to be held as a joint production between Garambura and Gaullica in Verlois.