Dzhuvenestan

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Most Serene Republic of Dzhuvenestan 𐬐𐬊𐬨𐬀𐬭𐬀 𐬈𐬀𐬨𐬀𐬥𐬍 𐬛𐬲𐬎𐬬𐬈𐬥𐬈𐬯𐬙𐬀𐬥 (Dzhuven) Komara Esmanî Dzhuvenestan | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Heta dawiya dinyayê Until the end of the world | |

| Anthem: "Ey, Dzhuvenî!" "Hey, Dzhuven!" | |

| Azagartian Standard | |

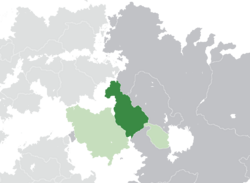

Location of Dzhuvenestan (dark green) in the Ayar Congress (light green) in Northwest Ochran (dark gray) | |

Location of Dzhuvenestan's governorates and their capitals | |

| Capital | Arvemşahr |

| Official languages | Dzhuven |

| Recognised national languages | Alcaenian, Southern Dzhuven, Qavar |

| Recognised regional languages | Balecian, Halysian |

| Ethnic groups (2020) |

|

| Religion | Melekism (official religion) |

| Demonym(s) | Dzhuven, Dzhuvenestani, Dzhuveni |

| Government | Unitary directorial noble republic under a de facto military dictatorship |

• President | Afran Zomorodi |

• Magubadi | Iosip Lomidze |

| Legislature | Magistan |

| Establishment | |

• Collapse of Azagartian Empire | X C.E. |

• Mesogeian Takeover | 1638 |

• Independence from Mesogeia | 1802 |

• Overthrow of Anax Constantine II | 1892 |

• Zomorodi's Coup | 1991 |

| Area | |

• | 609,920 km2 (235,490 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 47,004,212 |

• Density | 77.07/km2 (199.6/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $452,411,780,163 |

• Per capita | $9,624.92 |

| Currency | Dzhuveni Toman (₮) (DZT) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (Dzhuvenestan Standard Time) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (CE) |

| Driving side | right |

| Internet TLD | .dz |

Dzhuvenestan, formally known as the Most Serene Republic of Dzhuvenestan (Dzhuven: 𐬐𐬊𐬨𐬀𐬭𐬀 𐬈𐬀𐬨𐬀𐬥𐬍 𐬛𐬲𐬎𐬬𐬈𐬥𐬈𐬯𐬙𐬀𐬥, Komara Esmanî Dzhuvenestan) and also known as Dzhuveneia, is a sovereign state in western Ochran. It borders the Empire of Tarsas to the west, the Mithridatic Sea to the north, Zilung Chen to the east, and Ħamrastan to the south. Dzhuvenestan's 47 million people occupy 609,920 square kilometers of land; denser groups huddle the coast and inland river valleys, while sparser bands of population reside in the central highlands and northern mountain ranges.

The area's first unique identity began developing in early antiquity, surrounding a Melekite-adjacent Hellenic myth where the pantheon of deities struck down the beast Thalatta in a cataclysmic war. The X Mountains in the north of the country were identified as the region where its body was sealed away by the gods. Later romantic versions of the myth state that Thalatta's tongue was sliced out over the central highlands and richened the earth with rivers of saliva and blood. The Kardo-Belisarian root word for tongue, dn̥ǵʰwéh₂sˀ, has been identified as a potential origin point for the name of the fertile river valleys of central Dzhuvenestan, and later the whole country. This foundational myth has remained in the public consciousness even following the establishment of the later Melekite mythos as state religion.

Today, Dzhuvenestan exists under the continued authoritarian rule of military strongman Afran Zomorodi. The twin pillars of the Melekite priesthood and the military regime stifle civil liberties, and the existing low-lying ethnic insurgency against the central government has slowed most development progress outside the central regions. Repressed ethnic and religious minorities, long sidelined under the Dzhuveni nation-state, clamor for autonomy or even independence. Continued border conflict with neighbor and enemy Halys continually threatens to boil over into war. Internationally, the nation finds itself a member of the Forum of Nations and the Ayar Congress.

Etymology

History

The first peoples to originate in Dzhuvenestan were the ancestors of the modern-day Balecian peoples, rising from nomadic life to sedentary city-states by around the 3rd millennium BCE. They were joined by the Azagartian peoples, which dominated the region for centuries. The region, formerly the Azagartian heartland, became a battleground of empires as first the Latin Empire and later the Empire of the East battled it out with the Azagartian Empire. Gradually, the Azagartian empire disintegrated and the tribes of modern-day Dzhuvenestan began forming a separate tribal, religious, and ethnic identity from the Aerionese in modern-day Mesogeia, with a distinct split finalized in around the first century CE. With inclusion in the wider Azagartian world came the peopling of Hellenic settlements along the southern coast throughout Antiquity; these later formed the power base of the Mesogeian dynasties seeking to secure control over Dzhuvenestan. In ancient times, the area was known to the Mesogeians as Balecia (Alcaenian: Βάχλο), and was administered largely as a frontier march. There, it remained one of the burgeoning empire's most fruitful sources ethnic trouble. During the time of the Bayarid conquests in the X century, a group of Turkic peoples later known as the Qavars came to settle in Dzhuvenestan.

Mesogeian rule

In the mid-17th century, the balance of power in the region was shaken by an ascendant Mesogeia, which recruited some Dzhuveni domains into a war that saw the former gain control of the region. The Mesogeians exacted a heavy toll on the region, with the production of agriculture exponentially increased as the emperors sought to create an Ochranian "breadbasket"; the mountains were stripped of their natural resources. There was sudden political pressure from increased extraction, along with the enforced spread of the Apostolic Church, co-official use of the Alcaenian language, and swift promotion of local Balecian and foreign Alcaenian fringe figures as client rulers or nobles. A system of nobility and serfdom developed in Dzhuvenestan, with some nobles created out of old, local tribal families while others were transplants from the Imperial motherland. The region was shaped by Mesogeian policies heavily as a result of the imperial desires to control the heartland of the Azagartian Empire, from which they claimed to have inherited the right to rule. By the time of the Thirty Years’ War (1770-1802), the Dzhuveni provinces had developed a reputation for lawlessness and disorder as the eastern fringe of the empire. It was there that an equally troublesome and reckless royal, Prince Michalis, was stationed. Feeling slighted by his remote posting, and confident that he could turn the tides of the war in Mesogeia's favor, Michalis rallied his troops to win back power. Though successful in large-scale ambushes such as at the Battle of Arvemşahr in 1797, Michalis' campaign instead solidified his reputation as a disloyal traitor, burning his bridges with the Imperial Family. The renegade royal continued his campaign to great success, wielding his smaller force in guerrilla tactics against a numerically-superior but beleaguered Mesogeian army. Following the famous (and perhaps apocryphal) hailing of "Caesar; nay, Imperator!" by his troops in 1800, he crowned himself Anax Michalis I, Prince of the Dzhuvens and shortly after signed the Treaty of Pharapoli, which established Dzhuvenestan's independence.

Independent Dzhuvenestan

Michalis largely made a poor ruler, and delved into psychosis as he tried increasingly desperate measures to keep the nation unified. Successive and more tame Anases were unable to right the course, and by the late 19th century, many of the remaining nobles realized that the Dzhuveni monarchs were pushing for nearly the same thing as the Mesogeian Exarchs before them: autocratic centralization, with the ancient rights and privileges of the nobility systematically stripped away to make room for the all-consuming State. Many nobles began scheming to overthrow the monarch and lead the nation for themselves, often appropriating ideas of Belisarian liberalism and ideas of plutocracy to suit their own ends of maintaining liberty for the upper classes. Eventually, a group of army officers dramatically overthrew the final monarch, Anax Constantine II, in October of 1864 as he was en route to his coronation. The nation descended into anarchy as a brutal, decade-long civil war ravaged the country. Finally, the nobles proved victorious; Constantine was hanged via show trial and the rest of the royal family, led by his son fled into exile in Mesogeia, where they groveled and pleaded to be allowed in. The ensuing Grand Republic of Dzhuveneia harnessed the nationalist and Romanticist movements of late-19th-century Belisaria and mixed them with local ideals to create a constructed sort of national identity apart from Mesogeian or Alcaenian influences. The new regime spun itself as the true expression of new national ideals of freedom from tyranny and protecting its way of life. A new constitution enshrined the rights of the aristocracy; many positions of old nobility and ancient tribal allegiances were fused together in a near-anachronistic fashion to simply government. Also created was a powerful Senate, which in effect ruled the nation (though a Council of Ministers, complete with two first-among-equals Minister-Presidents, at least nominally headed the executive branch). This political framework largely remains to this day, though it was most severely altered in 1984 following a series of riots, student protests, and internal disturbance amid an economic crisis that threatened to topple the noble system. A counter-coup by army officers in 1991 brought Air Force general Afran Zomorodi to power as an unelected military dictator, a position which he holds to this day.

Geography

Climate

Demographics

Ethnic groups

Dzhuven ethnicity is deliberately conflated with membership status in the national polity by official and private pro-government bodies. Historically, ethnic assimilation efforts were such that ethnicity was not even included as a category on censuses in Dzhuvenestan until 1990. As proper census-taking has been rendered impossible by decades of civil conflict, informal surveys and research have been done by outside bodies to ascertain the nation's ethnic makeup. A plurality of Dzhuvenestan's citizens (39%) identify as ethnically Dzhuven according to estimates made in 2020. At present, numerous other ethnolinguistic groups exist in Dzhuvenestan, including the Gerki, the Qavari, the Hellenes, the Balecians, the Zilung, and others. The Gerki, a group of tribes in the southeast of the country related to the Dzhuven, are the second-largest ethnic group in the nation at 21%. The Qavari, a Turkic ethnic group known for their historical affiliation with Judaism, make up 13% of the population, concentrated in the northeast. The Heliads and Balecians, at 9% and 8% respectively, together make up the plurality of the population of the northeastern coastal province of Balkhestan. The Zilung, a group closely related to those in Zilung Chen, make up 5% of the Dzhuveni population and largely inhabit the lands along the eastern Zilungpa border. Numerous smaller groups exist dotted around the urban and rural areas of Dzhuvenestan, and collectively make up the final 5% of Dzhuvenestan's population according to 2020 estimates.

The terms by which ethnic groups are discussed in Dzhuvenestan are largely rendered from an ethnic Dzhuven perspective. For example, the term "Heliadic" in Dzhuvenestan describes a group of people influenced by Aerionese people in Mesogeia and Perateians in Perateia. After centuries of interaction with non-Heliadic groups and relative isolation from other Hellenes, the Hellenes of Dzhuvenestan formed a unique identity distinct from any other Hellenic groups. The concept of "Dzhuven" as a unified ethnic identity is itself a recent construction. Until the Grand Republic formed, tribal identity dominated modern-day Dzhuvenestan. Tribal leaders performed the function of modern-day Dzhuven nobility; Gerki and Dzhuven tribes were considered to exist on a shared linguistic continuum, with differing regions and even individual tribes possessing dialects of varying mutual intelligibility. Starting under the rule of the monarchy and continuing under the noble republic, the state and dominant Dzhuven tribes engaged in a campaign of "Dzhuvenization" or [PITHY TERM], largely enforcing a standardized Dzhuven national identity under a new system of nobility. Those tribal groups which resisted to varying degrees in the northeast instead fell under the term "Gerki." The group began to coalesce around a shared identity in opposition of the Dzhuven majority. Today their numbers are mostly found in the northeast of the nation, but small pockets exist across the country, including in Balkhestan.

Language

The sole official national language in Dzhuvenestan is Dzhuven, a southern Azagartic language. Despite the linguistic diversity of the region, efforts have been made by successive Dzhuven governments to impose Dzhuven on the populace. Though speaking other languages has never been strictly outlawed in Dzhuvenestan, the sole use of Dzhuven for business and government purposes has been extensively promoted for over a century by central authorities in Arvemşahr. The standardized dialect of Dhzuven is the central, or Arvemşahr, dialect. The southern dialect remains spoken, but is confined to older generations and rural areas as efforts continue by the Zomorodi regime to promote the Arvemşahr dialect. Academic debate exists on whether the Gerki language is a unique language or a distant dialect of Dzhuven.

Most ethnolinguistic groups in Dzhuvenestan are associated with one or more distinct language. Besides the Azagartic languages, several other language families are represented in Dzhuvenestan.

Religion

Melekism is the official state religion of Dzhuvenestan. Though the practitioners of the nation's numerous minority faiths are meant to be provided protection under the law, they often face persecution and widespread discrimination. Non-Melekites, for example, are effectively barred from the military and most government jobs. In regions with separatist conflict, villages dominated by non-Melekite faiths are often targeted for military actions, surveillance, and even destruction at a far higher rate than Melekite villages. Melekism is considered by many in power as an essential pillar of Dzhuven national identity, and to question the religion thus marks the nonbeliever as close to treason. Though non-Melekites citizens make up a minority of the Dzhuven population, they make up the majority of refugees in nearby nations such as Zilung Chen and Mesogeia. Prominent minority faiths are Aletheic Nazarism and Ravshanism.

Based on estimates extrapolated from the 1990, 2000 and 2010 Censuses, a comfortable majority of Dzhuvens practice Melekism. No official recognition of an official denomination or sect within the religion has been made. The dominant school of thought in Dzhuvenestan, Mishurism, places emphasis on the mishur, a type of document that originated as a record of local tribal or priestly lineages, but have since evolved as spiritually-endorsed guides based on precedent and moral actions. Such documents hold wide-ranging advice on subjects ranging from marriage to conflict dispute to righting spiritual wrongs. Mishurism encompasses the majority of Melekite sects, with a significant minority instead falling under the Şerfedîn school of thought. This school places emphasis on mysticism. Rather than condemning the use of the mishur, Şerfedîn teachings see them as useful yet incomplete doctrines, far inferior to the unknowable and esoteric nature of God and his Seven Angels. To fill this gap, doctrines such as rigorous adherence to rituals, sacrifice, and the study of so-called "esoteric wisdom" such as astrology have all been historically explored. Mishurist and Şerfedîn schools both agree on the physical realm's four core aspects—air, fire, water, and earth—are sacred expressions not to be tainted.

Government

De jure, the government of Dzhuvenestan is a unitary republic with special privileges for its noble classes. The three-decade military dictatorship helmed by Afran Zomorodi has all but institutionalized itself over the top of the civilian government. The latter was suspended on Zomorodi's orders following the former's coup d'etat in February 1991. Dzhuvenestan was ruled under perpetual military emergency decree until the reformist 1985 Constitution was formally replaced by Zomorodi and the Magistan, or the Dzhuven legislative branch, in 2002. This constitution (in effect to this day) largely reverts the reforms made in 1985, and enshrines the armed forces as the ultimate authority over the state. The historical practice of dual rulers, each termed magubadi, were relegated along with the Magistan to functioning as mere rubber stamps for the armed forces. Zomorodi's position over the government is both permanent and temporary: his status as head of state, chief of government affairs and commander-in-chief of the armed forces is assured to him by the Constitution "until such time as the existence of Dzhuvenestan's proper government is secured and prosperity and peace reign over the nation." Such language continues the early rhetoric of Zomorodi and the coup plotters; rather than being subverters of democracy, they saw themselves as preservers of the "true" Dzhuven system from outside agitation and internal bad-faith actors. In ruling, Zomorodi is assisted by the Dzhuven National Salvation Organization (DNSO), a political quasi-party which serves to consolidate pro-regime ideologues and assist in shaping Dzhuven society according to Zomorodi's vision.

Executive branch

The executive branch of Dzhuvenestan is dominated by Afran Zomorodi as sole leader. As President, Zomorodi is endowed with broad executive powers.

Underneath Zomorodi operates the Revolutionary Salvation Command Council, or RSCC (not to be confused with the the Fahrani Civil War faction, the National Salvation Council). The Council consists of numerous DNSO party functionaries, which possess both broad legislative and executive powers. According to the 2002 Constitution, the Council elects a Chairman and Vice Chairman from its own ranks; these then become the President and magubadi (Prime Minister) of the country, respectively. The RSCC has largely supplanted the Magistan, or historical legislature of Dzhuvenestan. Members of the Council are often close associates or even relatives of Zomorodi's clan, and often act on his behalf. In the Council, as in most sectors of the Dzhuven government, neo-patrimonialism is highly pervasive.

Legislature

Officially, the Magistan, or Parliament, is the official legislative organ of Dzhuvenestan. A unicameral body, eligibility requirements to be elected to the Magistan include X, Y, and Z. Terms are typically five years in length, and one may serve three terms consecutively before being ineligible to run for the office again.

Law

Much like the nearby nation of Shirazam, Dzhuvenestan's judicial system is not perceived as a separate branch of government. Rather, the judicial system is entirely subservient to the Presidency and executive branch.

Military

The military of Dzhuvenestan is officially known as the Army of the Celestial Republic of Dzhuvenestan (ACRD). The ACRD is comprised of roughly 670,000 personnel, split into four branches: the Celestial Army, the Celestial Navy, the Celestial Air Force and the Celestial Guards. The first three branches function as the nation's conventional military, while the Guards operate as a strictly internal military force. The Guards are responsible for guarding sensitive government facilities, some counter-insurgency operations, border security, anti-terrorism procedures, and large-scale crowd control. A large amount of the ACRD's personnel and resources are currently engaged in combatting insurgency across Dzhuvenestan.

Owing to the longstanding dominance of Afran Zomorodi, the ruler of Dzhuvenestan and the head of the armed forces, the ACRD operates almost entirely without oversight from the civilian government. In areas outside of Arvemşahr, military units are reported to have engaged in extortion, robbery, murder, human trafficking, drugs production, and other crimes with impunity. The economic strain of Dzhuvenestan's decades-long internal conflict has both limited the budgetary sources for the ACRD and created a need for increased funding to properly fight, likely exacerbating the allegedly widespread criminal behavior. The military also holds significant direct influence over civilian government. Several high-ranking officers have served as top ministers or in other important cabinet positions in Dzhuvenestan after 1991.

Foreign affairs

Dzhuvenestan's foreign policy has been dominated by a long-standing rivalry with the Sovereignty of Halys, its western neighbor. The two nations fought two large-scale wars in the 1940s and 1970s. The latter war ended inconclusively, leaving a legacy of high tensions that continue to this day. The two nations hold mutual embargoes on each other, but low-level illicit and backchannel trade occurs frequently regardless. Both states' nationalist imagery often directly clash, to the point that Halysian rhetoric regarding the Dzhuven nation is often seen as genocidal. Both nations draw heavily on romanticized depictions of predecessor states; large numbers of Azagartian imperial artifacts were looted by Dzhuven "monument units" during both wars, and capturing the ancient ruins of Azagartopolis was a strategic Dzhuven objective in the Second Halyso-Dzhuven War. In terms of outside powers, the Dzhuven government post-1991 has frequently courted the Realms of Alanahr and the Empire of the East for development aid and diplomatic support; the latter two nations see Dzhuvenestan as a counterweight to prevent the growth of Halysian power in the eastern Periclean. Through these relationships, Dzhuvenestan indirectly associates with Empire of the Latins. Military supplies, utilized by both the Dzhuven military and various rebel groups, are predominantly acquired from east Belisarian nations like Usezoya, Ludvosiya, and to a lesser extent Velikoslavia. The Dzhuven military generally acquires weapons from these nations' defense industries directly or from production under license; rebel groups typically purchase surplus from the post-East Belisarian Cold War informal market or manufacture weapon models without license.

Diplomatic operations are conducted through the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA). Dzhuvenestan is a member of the Forum of Nations, as well as a handful of international organizations. Meaningful participation in many organizations is hampered by the nation's longstanding civil conflict and poor human rights track record.

Education

According to the last complete Dzhuven census, roughly 90% of the population was literate as of the year 1990. Current government estimates place the rate around 95% at present. Historically, education was seen as the primary means for enforcing a united Dzhuven identity on the populace. The school system was used to impose the Dzhuven language, as well as to spread a Dzhuven-centric view of the region's history. As such, the Dzhuven education system is highly centralized and standardized under the Ministry of Science, Education and Technology (MSET).

Education is compulsory in Dzhuvenestan for 12 years, from the ages of 6 to 18. The first six years are sorted into elementary education or dabestan; the next three fall under junior secondary or Motovasseteh avval. Junior secondary schools are responsible for establishing a child's aptitude toward education specializations. The final three years fall under Motovasseteh dovom, or senior secondary. This level is meant to prepare students for careers in semi-skilled labor and prepare them for tertiary education. In 2002, in line with the new constitution, senior secondary school was made compulsory for all citizens. Such a move generated outcry among parents, as the tuition fees to enter said schools were not abolished for lower-income families.

Tertiary education in Dzhuvenestan is entirely state-managed.

Administrative divisions

Dzhuvenestan is legally divided into sixteen governorates (Dzhuven: parêzgeh). Each corresponds roughly to a traditional province of Dzhuvenestan, with the exception of Balkhestan Province, which is divided into three governorates (Eryanopoli, Salm, and Gûzana). Per the 2002 Constitution, governorates are led by officials appointed by the central government in Arvemşahr. As a unitary state, Dzhuvenestan has a legal uniform code across all governorates. Governors are often pliant noblemen or officials that are given their positions as rewards for loyal service to the regime.

| # | Governorate | Capital |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Arvemşahr | Arvemşahr |

| 2. | Eryanopoli | Marga |

| 3. | Salm | Salm |

| 4. | Behistun | Shemiran |

| 5. | Barzan | Barzan |

| 6. | Rayastan | Darhol |

| 7. | Bahdinan | Karçal |

| 8. | Kevirestan | Khoy |

| 9. | Kherbasan | Berçem |

| 10. | Bakhtaran | Dezhe Şāhpūr |

| 11. | Anaşa Şêrko | Pirakevn |

| 12. | Khatuna Fekhra | Şekhan |

| 13. | Gûlestan | Fereydoun-Qehreman |

| 14. | Şêranestan | Berfêgiren |

| 14. | Gûzana | Tisbun |

| 15. | Ermān | Sāri |

| 16. | Damezman | Khotan |

In addition, the Balkhestan Autonomous Government (BAG) has been born out of the complex nature of Dzhuvenestan's longstanding civil conflict. Without legal basis to exist within the Dzhuven legal framework, the BAG nevertheless operates as a quasi-state, claiming to be under Dzhuven central authority despite violating the Dzhuven constitution. Due to a lack of military resources to suppress the BAG and their longstanding entrenchment in the Balkhestan region, the Zomorodi government tacitly allows for their continued existence but refuses to grant them official recognition. As such, disputes over separation of powers and government duties between the region's and governorates' political bodies are frequent and muddled.

Economy

Despite ongoing civil unrest, Dzhuvenestan possesses one of the fastest-growing economies in Ochran and the wider world. Recent figures indicate a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of $452,411,780,163, and a per capita GDP of around $9,624.92. The nation is a secondary economy, with its primary industries being steel milling, iron mining, and general sweatshops. Its primary export partners are Zilung Chen, Mesogeia, and Halys. Many Dzhuven sweatshop goods, however, end up across Belisaria and Ochran as a cheap, local alternative to similar goods produced in the Mutul. Owing to the current political crisis, most economic growth is restricted to the capital, Arvemşahr, and government-controlled coastal ports. Damage to infrastructure caused by fighting and sabotage has also hampered growth in many outlying regions.

Historically, the Dzhuven region was tied to global commerce as a resource-extraction economy. In the pre-modern era, Mesogeian imperial authorities first populated Dzhuven river valleys with cash crop plantations before expanding their extraction to iron mining. Existing food agriculture, cash crops, and mining generated great wealth at the time, but this remained concentrated in the hands of Mesogeian and allied nobles, while the vast majority of the Dzhuven populace saw little of these profits. This trend continued until the Industrial Revolution took hold of an independent Dzhuvenestan in the 19th century. A growing industrial bourgeoisie threatened the power of the Dzhuven monarchy and aristocracy, leading to the latter co-opting industrial holdings into their noble estates as a means of political security. Plentiful supplies of both iron and coal provided ample fuel for the nation's industrialization.

The informal economy in Dzhuvenestan makes up one of the largest shares of a national economy in the world. Rebel groups, criminal organizations and isolated Celestial Republic Army troops alike grow opium poppies both for personal consumption and for export. Though officially illegal, opiates and other substances are both widespread in the country and frequently exported: in 2020, around 400 metric tons of opium alone were produced in Dzhuvenestan, with most being smuggled into North Scipian and Eastern Belisarian markets. Funds from exports are often used by military units and rebel groups to acquire arms and to supplement logistics networks strained by decades of conflict.

The rail network of Dzhuvenestan comprises of 21,731 km (13,503 mi) of railroad. Much of the network is in 1,680 mm Ochranian gauge, but various spur lines and industrial railroads in Dzhuvenestan's hilly regions utilize narrow gauge. Operated by state-owned Dzhuven Celestial Railways, the network plays a vital role in maintaining Dzhuvenestan's economic growth. The western extremity of the Trans-Ochran Railway crosses the center of the nation, from the eastern border with Zilung Chen to the capital of Arvemşahr. The rail network of Dzhuvenestan is of such importance that the government devotes a paramilitary force, the Railway Protection Force, to safeguarding it from robbery and attack. The Force also operates as a law enforcement agency, empowered to enforce railway safety ordinances and regulations.