Mniohuta

Confederation of Mniohuta ᐅᔭᑌ ᒼᓂᐅᐦᑕ 11 official names

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motto: «ᐁᓬ ᖧᐊᑲ ᓬᔪᑎᔦᑭᔭ, ᐅᐘᐁᐃᓬᐊ᙮» "In great endeavour, union." | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: ᐅᐩᐊᑌ ᐅᓬᐅᐘᐣ Oyáte Olówaŋ "Song of the Nation" | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| People's Hymn: ᑭᑭᙾ ᓬᐅᑕ ᐦᐁᐦᐁᐱᔭ Kikiŋ Luta ȟehépiya "For the Scarlet Hills". | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Location of Mniohuta on Earth. Members of the Norumbian People's Alliance in Blue. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Political Map of Mniohuta | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Wokheya | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Largest city | Walgroinzin | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Mniyapi | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recognised regional languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ethnic groups (2020) | List of ethnicities

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | List of religions

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Mniohutan Mniohuti (plural) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Libertarian socialist federated clan republic semi-direct democracy | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Premier | Siŋtemáza Hotah | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• High Chief | Odakota Akecheta | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Conclave of the Confederacy | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Council of Elders | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Conclave of the People | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Formation | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Around 12,000 BCE | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• Founding of Wokheya | 935 BCE | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Asherionic Wars | 1805 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Articles of Confederation | April 14th, 1822 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Absorption of the Republic of Waziyand | January 20th, 1846 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• The Spring Constitution | November 3rd, 1865 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• Total area | 897,115 km2 (346,378 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Water (%) | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 2020 census | 29,874,102 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Density | 30.19/km2 (78.2/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Total | $457,073,760,600 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Per capita | $15758 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gini (2015) | low | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| HDI (2015) | very high | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Mniohutan mazaska (₼) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC -5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Driving side | right | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Calling code | +68 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Internet TLD | .mt | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Mniohuta (/mniːoʊhʊtjæ/ muh-nee-O-hu-ta), officially the Confederacy of Mniohuta, is a country in northeastern Norumbia. Its consulates cover a landmass of around 897,115 square kilometers (346,378 square miles), bordered by Elatia to the Northwest across the Hinapa strait, the Hinapa Sea to the West, Winivere Bay to the North, Awasin and Moxaney to the Northeast, Chenes to the West, and Gristol-Serkonos to the South. The majority of the 29,000,000 citizens of Mniohuta live in major cities such as Walgroinzin or in the central plains along the many rivers that snake along the thanzanye plain. Wokheya is the capital of the country while Walgroinzin is the largest and most populous city in the country. Mniohuta is characterised by a largely indigenous population, with a significant Ottonian-Mniohuti creole group, and a handful of Norumbian indigenous groups and other minorities from nearby states.

Various indigenous peoples have inhabited what is now the thanzanye plain since at least 12,000 BCE, remaining largely nomadic until cultural shifts brought on by the Years of Ash led to the foundation of what is today Wokheya in 925 BCE by members of the Thikapaha band of the Khowakota tribe and the formation of similar settlements in Mniwa and Oskopa in the following century. Unlike many of its neighbours, the central portion of Mniohuta has never been colonised or settled by a foreign power, with indigenous people living largely undisturbed due to a number of geographic barriers. A handful of Ottonian Fretrekeriners made their home on the Northeastern shore of the country, journeying from Ottonia and later Wazheganon fleeing religious persecution and in pursuit of a religious vision into what is today the consulates of Walgroinzin and Waziyand. While traditionally it was believed that the arrival of the Ottonians was the first long-term contact of indigenous Mniohuti with outsiders, modern historians believe that Haratago nomads and explorers passed through the prairies of central Mniohuta at some point in the 10th or 11th century while journeying to modern day Elatia and Enyama.

By 1500 BCE, many tribes of the thanzanye plain had organised themselves into proper cooperative city-states which co-existed with a number of still nomadic tribes, both having traditionally tribal governments; though, in the case of the city-states many were beginning to form more complex systems of governance. Rivalries that pre-dated the formation of settlements tended to persist, particularly between the Khowakota and Hinhanata who had for centuries been staunch rivals that engaged in semi-regular conflicts that would lead to shifting alliances and changes in the balance of cultural power. While these conflicts often led to skirmishes and occasionally outright wars, these early states were also marked by their willingness to compromise and settle disputes in less violent manners such as game hunting matches and lacrosse (čháŋškopa, ᐨᐦᐋᐣᐨᐢᐢᑯᐸ) tournaments. This fairly amicable culture was reflected in willingness to barter and interact (and in certain cases, integrate) with the Ottonian settlements along the Northern coast and contributed to their generally positive relationship. Despite the growing centralisation of Mniohutan city-states, it was not until the arrival of Asherion in the mid-1800s that the idea of creating a proper nation-state was more thoroughly popularised amongst tribal groups.

Representatives from Mniohuta including the Chief of Wokheya and founder of the confederation, Kicking Bear (Wanátȟó, ᐘᓈᙾᐦᐆ), would participate as delegates in the Federative Republic of Great Norumbia's short-lived legislature before the republic's collapse at the hands of the coalition. Upon his return to Wokheya, Kicking Bear called for a meeting of the tribes in what would be called the Eight Fires Council, an effort to achieve consensus on the formation of a state and to continue in spirit the revolutionary ideals of Asheiron with Mniohuti characteristics. The Council ended after a month of deliberation with the signing of the Articles of Confederation, formalising the role of High Chief in the early confederation and allowing the confederacy to send representatives to the Congress of Thessalona to negotiate what were to be Mniohuta's borders. From the Congress, the Confederation of Mniohuta was formally recognised as a sovereign state alongside the short-lived Republic of Waziyand. A decade later the now largely creole and indigenous Republic of Waziyand was peacefully absorbed into the Confederation, leading soon after to the addition of greater democratic concessions to the Articles of Confederation which would later lead to the writing of the Spring Constitution (Wiwíla Wóopȟe, ᐏᐑᓬᐊ Wᐆᐅᑊᐦᐁ). Contemporary Mniohutan history has largely been characterised by tensions with Elatia over the ceding of the Wiyopeyata peninsula as a result of a Numerian rebellion and the Osowanon Wars.

The Government of Mniohuta is a libertarian socialist federation in the Council Democracy (Thiyóthipi School) and co-operative traditions, with a nationally elected Premier who acts as a representative of the nation and presides over the conclave of the people, and a council elected High Chief who serves a largely ceremonial and spiritual role within the nation. Since the signing of the Spring Constitution in 1865 a system of conclavism has been a key part of Mniohutan politics, with 580,000 nested conclaves at its base, it is a system that is heavily dependent on almost total participation and consensus of the populace. At the national level Mniohuta has a bicameral legislature with a Conclave of the People and Council of Elders; however, the Conclave of the People has de jure total control over national decision making. The Council of Elders exists in its role largely as an advisory body, with the only real responsibility of the Council being to elect a High Chief upon the death or recall of the previous and to provide advise to legislation.

Because of its political evolutionary path, the traditional economic systems of the early Mniohutan city-states evolved into a system of co-operative economics, with basic-needs traditionally being decommodified and most businesses being a hybrid of consumer and worker cooperatives (or are otherwise owned by the state). Major industries and exports include diamonds, iron, textiles, forest products, shipbuilding, railway engineering, and tourism. Mniohuta ranks highly in international measurements of political freedoms and participation, government transparency, education, and quality of life. International experts consider Mniohuta to be a middle power with a geopolitically strategic and central role on the continent. It is a member of a number of international organisations such as the International Observatory of Labor, Osawanon community, and is a founding member of the Norumbian People's Alliance (Hahowin).

Etymology

The origins of the name Mniohuta stem from the Mniyapi word Mnióhuta (ᒼᓂᐅᐦuᑕ) which roughly translates into anglish as "Land by the Sea" or "Land of Coasts". The first use of the word Mniohuta was uncovered in a letter from the Third Chief of Wokheya, Igmútȟuwá (Lion Chaser, ᐃᐨᐠᒧᖪᐘ) of the khowakota tribe to Wíyamázkazi (Golden Eagle, ᐏᔭᒪᐢᑲᓯ) of the Mnokiwoju band in which he invited his fellow chief to an alliance "Rest your weary legs, new life springs from our land by the lake like the yarrow from the grasses." The term gradually became synonymous with Wokheya and many of the other settlements and tribes that dotted the shores of the Hinapa Sea, growing more popular as it spread inland through word of mouth of the nomadic tribes moving inland during the summers. While the term Thituwan was more popular for describing the people of the Mniohutan prairies than its modern demonym, describing the land as one by the lake was the most conventional as most tribes would eventually make their way back to it during the winter resting season. During winter counts were the primary means of tracking the building popularity of the word, especially in documents after 1258 CE, with the name finding itself gradually finding itself equally applicable for the settlements in Skhabela and Oskopa. When first contact was established with the Ottonian Fretrekeriners, the first natives they had encountered were the Waziyata tribe of the Northern coast, with the religious exiles using the tribe's name and combining it with the Ottonian word "land" to create Waziyand which grew synonymous with the country's North (and more broadly towards Mniohuta in general until 1870). Following the adoption of the article of confederation a few formal names were considered, but Mniohuta rose to the top for how general it was and how frequently the term had become and when the delegates arrived at the Congress of Thessalona it became the internationally recognised name of the country. While this was largely done out of the wishes of the Thituwan people, this was also to avoid confusion with then then newly created republic of Waziyand to the North.

Demonyms

Each of the major languages and dialects of the country tend to have their own respective twists with respect to demonyms, usually hinging on varying word structure or minor differences in lettering with similar degrees of pronunciation. In its anglish noun form "Mniohutan" is almost universally considered the preferable term, with the adjective "Mniohuti" largely only being used to describe the population in a plural sense; though it is sometimes considered interchangeable with Mniohutan.

Official title

Officially, the country is referred to as the Confederacy of Mniohuta (Mniyapi: Oyáte Mnióhuta, ᐅᔭᑌ ᒼᓂᐅᐦᑕ), with the Mniyapi title being the most commonly used due to the language's role as a language of culture, trade, and business. Alongside the official Mniyapi title, there are 11 other recognised titles in each of the most common languages of the various regions of the country. While Mniohuta has strayed farther from its confederal roots and shares far more characteristics with a loose federation in the modern era, it is still occasionally referred to colloquially as "The Confederation" or more regularly as "The Great Friendship" (Kȟoláŋka, ᐠᐦᐅᓬᐊᐣᐨᑲ) by citizens. While there was a sizeable movement in Walgroinzin in 2003 on the matter of removing the title of "Confederacy" as a national prefix for Mniohuta, there was very little popular support for the change and it ultimately was voted down in what regional nested concalves it managed to rise to.

Geography

Making up a total land area of 977,728 km2, Mniohuta is the third smallest country on the Norumbian continent and is geographically central. Along the northern border of the confederacy is Winivere bay and to its West is the Hinapa strait and the Hinapa sea. Bodies of water aside, the northern Wazepiya Mountain Range is the major defining feature of Mniohuta's north and provides the majority of the country's mineral wealth. The Wazepiya range is also home to one of the highest mountains in the country and in the Winivere Cordillera, Mount Wichahcala, which stands at 4,421 meters. In the Southeast are the Osowanon Mountains which mark the primary border between Mniohuta and several of its neighbours. The heart of the nation is largely defined by the Thanzanye Basin River System which stretches from both mountain ranges through its tributaries down to the nation's southern coastline. To the nation's East across the Hinapa strait is Elatia, to the south is Gristol-Serkonos, to the West is Chenes and a narrow strip of land connecting it to Moxaney, and to its Northeast is Awasin.

While the mountains remain prominent geographical features for the nation, the vast majority of the country is enveloped by the Thanzanye Plains. Running through the central section of the country is the Mnisose River which runs through Wokheya, and its distributary the Wazaze River which, similar to its parent river, empties into the Hinapa sea. While a majority of the water that flows into the aforementioned rivers comes from the mountains, Lake Oskopa and Lake Ciz also serve as major reservoirs that feed into the river system (though they themselves get a majority of their water from mountain snow-melt, glacial melt, and runoff). Lake Oskopa is the largest freshwater lake in the country, occupying roughly 2,158 km2 and reaching a maximum depth of around 706 meters, it is the remnant of a prehistoric lake known as Lake Iya which at one point connected to the Hinapa sea at the conclusion of the Last Glacial Maximum.

Climate

Mniohuta's climate is largely defined by its Semi-arid climate, with warm, humid Summers and Springs driven by warm air blown North from Gristol-Serkanos which bring rains and summer storms to the flat and hilly prairies that compose most of the nation's heartland. The north is far colder, with the Wazepiya Mountains acting as a natural barrier that limits the cold winds from The Boeric to Mniohuta's north. Winters often bring heavy snow to the north, often bringing meters worth of snow each winter; while the Thanzanye Plain often gets at least a few centimeters each season, with the stray snowstorm sometimes bringing more in particularly cold years. Along most of the major mountain ranges and peaks in both the North and South of the country are thick boreal forests that provide shelter for much of Mniohuta's megafauna alongside the grassy steppes. Temperate coniferous forests are rarer but can be found in particularly high densities along the Southwest. Because of the unusual geography of the country there are a number of small cold deserts in the North, the most notable of which being Čhasmú pahá (ᐨᐦᐊᐢᒪ ᐸᐦᐊ), a protected reserve south of Osmaka.

The Northeast of the country is largely characterised by its subboreal climate which keeps the North temperate and dry in the Summers and cold and wet in the Winters. Despite the mountainous terrain, there are a number of flat lands and natural ports that are ideal including, most famously, the port at Walgroinzin which shields ships from the rough winter seas and stray ice bergs and is one of the largest natural harbours in the country. Grasslands in the Northeast and West are usually lightly forested and closer to cold steppes seen in other countries in the north of Belisaria. Much like in other parts of the country there are a number of sizeable boreal forest scattered about the North. Because of shifting plates along the coast, seismic and volcanic activity in this part of the country have been a re-occurring historical theme: most notably with the eruption of Mount Pȟáŋéta's in 1982.

Western Mniohuta's coast along the Hinapa sea is much like the rest of the country's heartland, largely featuring low hanging cliffs and flat shores that meet the rich prairies and West-flowing rivers. Because of the largely flat terrain and occasional mixing of cold and warm weather, cities in the heartland of the country are especially at risk for natural disasters such as tornadoes. Thunderstorms are also a frequent feature of Western summers, with hail damage being an occasional concern in the Spring when warm winds from the South meet the cooler winter winds from Elatia.

Biodiversity

Mniohuta is home to a wide variety of endemic species, with thousands of native plants being recorded in the Journal of Multifariousness and a wide selection of herbivores and carnivores also being scattered throughout the country. In terms of plant life, a great diversity of wild flowers including the Thanzanye Poppy (Tȟókahu wahíŋkpe úŋ ziyápi, ᖫᑲᐦᐅ ᐘᐦᐃᐣᐠᐠᐯ ᐆᐣᐠ ᓯᔮᐱ) are especially common in the Spring and last through the Summer and early Fall. Certain species of flower such as the Oskopa blue columbine (Utahu-čhaŋȟlóǧaŋ, ᐊᑕᐦᐊ ᐨᐦᐊᐣᐦᓬᐅᐸᐣ) grow year-round and are very frequently used in Wakanist herbal medicine and tea. Maple trees can often be found in forested areas and along rivers and are used frequently by indigenous communities, with certain saps being used as sweeteners,

dyes, and as treatment for diseases. In the handful of cold deserts scattered throughout the country, a number of Cactaceae species thrive, including some more well known varieties such as peyote (Uŋȟčéla, ᐊᐣᐦᒉᓬᐊ) which are frequently used for cultural and religious ceremonies for its psychadelic qualities. More common along the mountains and wetter coasts of the north is the Wazepiya Pine which accounts for a majority of the coniferous trees that exist throughout the country, though particularly concentrated in great numbers in the Wazepiya mountains. A wide variety of bush based berries are common at middle altitudes and along rivers on the plains, with the Norumbian Gooseberry and Kadoka Blueberry being exceptionally common due to agriculture and natural ease of spread. The River Plum is also especially common near rivers and lakes, alongside other fruits such as apples, cherries, apricots, and peaches which were introduced through active seeding efforts or spread from neighboring countries.

Mniohuta is also home to a wide variety of land-based mammals and megafauna which have thrived in the last several centuries due to conservation efforts and selective hunting induced by religious and cultural movements. Mniohuta is particularly well known for its variety of Pantherinae and other species of the Felidae family; many of which are believed to have evolved from Prairie Lions to fill specific biological niches, among these species are: Prairie Cheetahs and Mountain Lions. The Norumbian Grey Wolf can also be found in scattered packs along the Wazepiya Mountains feeding largely off stray herds of Bison and White-tailed deer and are often found in competition with Mountain Lions and other mountain-bound predators. The Forest Pygmy Mastadon can be found in small herds throughout the north of Mniohuta, occasionally traveling down into the plains and with scattered herds sprinkled through the Southeast. Efforts to reintroduce mastadons to other parts of the country have showed mixed success, but generally they have been left to their own devices outside of efforts to protect them from ivory poachers. Bison are the most common of the larger herbivores in the country, often constituting herds of hundreds or even thousands that migrate across the Thanzanye Plain depending on weather and prevalence of grazing lands.

The Thanzanye Basin River System is home to a wide variety of fish and other water-based wildlife, including a number of semi-aquatic mammals such as the Norumbian River Otter, Mniohuti Castador, and Norumbian Mink. Salmon are a common feature along Mniohuti rivers, often migrating from the lakes in Mniohuta's East to the Hinapa Sea in the late Summer to early Winter. Other than salmon, fish such as Mnisose Pikeminnow, Huíyata, Ištápiya, and Hóbu among other smaller minnows and the like are common. Because of the country's rising population and growing energy needs, dams and overfishing have placed a strain on certain species; with salmon in particular facing challenges that have forced engineers to adapt in order to preserve populations. Thanks to conservation revitalization efforts started in the 1960s and the introduction of a nationwide community fish farming and breeding efforts, their populations have largely recovered over the course of the last three decades. Along the north coast and in the Hinapa sea larger sea faring creatures such as walruses, beluga whales, orcas, bowhead whales, White-beaked dolphins, and Ringed seals are common and can often be spotted from shore along the country's many coasts.

Casitdors are the largest members of the Castoridae family and among the largest water-faring herbivores in the country.

History

Evidence of human habitation in what is now Mniohuta dates back to at least 10,000 BCE as early nomadic humans travelled South from present day Wazheganon and Awasin to the Thituwan basin. Oral tradition and archaeological records show that the early settlers were largely nomadic, following herds of mastadons and bison and engaging in the hunting and gathering of wild plants. As tribes grew bigger and herds split apart people spread across the prairie and even further to the North and would, on occasion, re-convene at certain geographic points in order to trade and share goods and stories. This tradition gradually evolved into the annual Sun Dance, a tradition that has persisted into the modern day and has been understood by anthropologists to be the foundation for most cultural and religious advancements over the course of the last millennium.

Gradually dialects began to form and differences in languages began to surface, the largest since antiquity being Khotayapi and Winhanayapi, kept only from drifting into entirely different sub-families beyond the subdivisions by the regular interaction of tribes and the development of common trade languages such as Mniyapi and Wíyutȟapi (ᐏᔪᖬᐱ, sign talk). As the tribes became more distinct, certain inter-tribal rivalries would come and go, but a majority of warfare was conducted as a result of competition over herds of bison or mastadons alongside inter-tribal disagreements of varying degrees. One such example, described in oral tradition as The Three Bison War (Yámniéȟčaka Okíčhize, ᔭᒼᓂᐁᐦᒐᑲ ᐅᑭᐨᐦᐃᓭ) led to the clashing of the Wiyohutakota and the Mitoyada tribes over a breeding pair of bison that led to three days of bloodshed that concluded with what is perceived today as a tornado interrupting the battle and the marriage of two warriors from the opposing tribes. While often what evidence of this period exists does so through oral tradition that was put onto paper in the 19th century, Mniohutan academics and religious scholars believe that they are all largely based on true stories mixed in with elements of hyperbole and mysticism. Many scholars hold that through the annual Sun Dance these stories and legends would be passed between shamans who would then eventually add their own twists which is where a majority of the elements of mysticism are believed to have come from. Archaeological records from epigraphic inscriptions at dig sites across the country tend also to lend credence to these stories, with the Tale of the Lion's Cub (Ohúŋkakaŋ Tȟamúčhiŋčála, ᐅᐦᐅᐣᑲᑲᐣ ᖬᒼuᐨᐦᐃᐣᒐᓬᐊ) being inscribed in its entirety on a rock near Ipha with a lion's skull and that of its human companion placed beneath the inscription. In later years, evidence of basic writings and the earliest forms of modern Norumbian Script were found on the hides of buffalo used for Winter Counts; though, symbols used to transcribe meaning over proper syllabics would still take precedent for the next several centuries.

Gradually life within Mniohuta began to grow more pastoral as populations of the indigenous people continued to grow. While hunting Bison and other large mammals was no less important to a majority of the tribes, certain bands began to domesticate buffalo calves; a practice which was gradually transmitted across the plains until a majority of tribes had taken up the practice. These domesticated buffalo would travel with the tribes, acting as a reserve of food in low hunting seasons and providing milk, cheese, and occasionally meat. Alongside domestication of buffalo, long term agriculture also became a growing practice, with many tribes often planting maize, beans, and squash which began to add to the already present practice of the gathering of wild plants as an essential part of Mniohutan diets in their fall and spring camps. Early attempts at drying and storing foods for later use became more frequently employed, but were not always prioritized because of the difficulty of transporting large amounts of food without the use of pack animals. It was also around this time that records of early culture began to grow more clear as writings and inscriptions grew more advanced in their detailing, with evidence of the tribal communalism that forms the backbone of modern Mniohutan society existing since the inception of these early records and describing the varying degrees to which communities adopted these systems and how they played into other cultural fixtures such as religion. The importance of the tribe (Oyáte, ᐅᔭᑌ) as a social unit over the individual was increasingly stressed by shamans and faithkeepers, with Kinship networks (Thiyóšpaye, ᖨᔪᐢᐸᔦ) also playing an essential role in this structure, particularly in terms of the layout of tribal camps.

The Years of Ash

As populations continued to grow, the plains and forests of Mniohuta were faced with a period of extensive overhunting on the part of the indigenous population. Species such as the Forest Pygmy Mastadon and Norumbian Castador were pushing well into the realm of being critically endangered, and several large bird species that had been native to their portion of the continent had been driven to extinction, in turn diminishing the population of native predator species. Buffalo herds too were beginning to feel the stress of overhunting which, in turn, built towards growing competition between tribes which culminated in a series of wars and skirmishes that only served to further fuel rivalries. Hunting solely for sport was also a growing phenomenon, with some warriors intentionally going after animals such as bears, lions, and wolves as part of ceremonies of maturity which contributed to a growing culture of waste that put further strain on the food cycle. The growing employment of Mourning Wars to replace fallen warriors and tribe members lead towards a growing practice of indentured service and in some instances outright slavery. These cultural and environmental developments contributed to polarization between the various faithkeepers whos views had begun to align further with their tribes because of the building rivalries. Historically faithkeepers had been in relative agreement over values, but because of controversies particularly brought on by the introduction of forms of slavery and the increasingly violent culture, there was a strong sense of greater schism within many religious circles.

In the Summer of 887 CE, Mount Pȟétawókh (fire lodge, ᑊᐦᐁᑕᐓᐠᐦ) violently erupted, covering much of the Thanzanye plain in ash and drowning the skies for a period of 6-8 months in ash laden clouds. Pyroclastic flows from the initial eruption also wiped out a number of settlements that had been situated within a few kilometers of the volcano, with harrowing tales from refugees from the initial disaster believed to have formed the basis for many of the legends that would develop in the wake of the disaster. The initial affect was a regional cooling that lead to a weak growing period during the harvesting season and the dying out of many grasses across the plains and the death of many herds of buffalo. The ensuing famine killed roughly 25% of the population in what is today Mniohuta, and lead to the migration of many Thituwan from various tribes to the North seeking new pastures and farming land in the South of modern Wazheganon. The remnants of this group in the country can trace their lineage to the Tonáyaŋká tribe who continue to reside in the North East of modern Mniohuta. While in some instances this lead to greater conflict over the scarcer resources, many chose to flee towards areas that were less affected which tended to be areas that practiced long-term food storage and sustainable agriculture. The generosity of these communities when caring for the refugees worked its way into legend and played a major role in cementing communalism and the doctrine of "community above all" into the culture. As the ashes settled and people began to return to their traditional lands, the flourishing of crops in the growing ash-laden soil and the survival of semi-sedentary agriculture communities was taken as a sign by survivors and greatly expedited the shift from primarily migratory tendencies towards semi-sedentary life.

This period was viewed by most shaman as a punishment from the Earth Spirit (Íŋyaŋ, ᐃᐣᐨᔭᐣᐨ) for overhunting the land, hunting for sport, introduction of evils such as indentured servitude, and increased bloodshed between tribes in the pre-eruption period. It is viewed by most modern historians as one the primary reason for sedentary life even taking root as early as it did, as well as playing a significant role in religious re-unification and limited standardization. At the next year's Sun Dance, faithkeepers emphasized the importance of sustainability and living as one with nature, pointing to the limited impact on more agriculture centered communities during the Years of Ash as evidence that their people need to change their ways lest Íŋyaŋ punish them again. Because of this, the idea that each and every animal was in one way or the other your brother or sister became universally ingrained into Thituwan culture; particularly in the case of the buffalo and to extent the mastadon who were seen as complete equals to humankind. Hunting them for anything other than the sustenance of oneself or one's community would bring dishonor to one's spirit and bad luck to one's band, and showing disrespect to them in death was considered equally shameful. Likewise, this lead to a number of religious reforms which turned the region's primary faith into a more organized tool for enacting social change and solidified the importance of the Thiyóšpaye (Kinship network, ᖨᔪᐢᐸᔦ) as a social unit. Choosing peace before war was ingrained into the region's psyche, with war being considered a last measure behind competitions, games, and above all else outright diplomacy. While conflict was never totally avoidable, this overnight reduction in combat changed the nature of Mniohuti society and helped lay the roots of the first city-states to form on the plains.

City States Period

Wokheya was the first of the larger permanent settlements to begin solidify as a permanent settlement in 919 CE, with the site previously being used as long-term settlement for those who were either too old, too young, too physically impaired, or were generally uninterested in continuing to migrate in pursuit of the buffalo. Historically the area had been used as a Summer camp by the Khowakota Oyáte (Khowakota Nation, ᐠᐦᐅᐘᑯᑕ ᐊᑎᐅᐣ) who grew crops and dried foods for the winter, with typically only members of one's Thiyóšpaye staying behind past the Fall to protect family. It is believed that because of the inflated importance of the Thiyóšpaye following the years of ash more people were gradually drawn to live in settlements such as Wokheya in order to avoid divisions within these social groupings. It is also believed that because predators such as the prairie lion and wolves would sometimes raid these settlements as their populations began to boom, more men were required to defend it which sped up the process of settlement. As the settlement continued to grow, more advanced agriculture practices began to develop alongside greater long-term drying and storing methods to keep populations fed year-round. In order to more efficiently keep out predators, wooden walls were constructed and earthen lodges began to replace the more mobile tipis used by those who were migrating.

By 943 CE, Wokheya had begun to morph into a larger town as the Khowakota began to more broadly shift towards sedentary life in the long-term aftermath of years of ash, with new social roles to deal with this new way of life being adopted. One of the most notable social developments was the evolution of consensus decision making for decisions that would affect the community at large. During the migratory period, Thiyóšpaye would meet to elect a representative to the Omníčiye (camp council, ᐅᒼᓂᒋᔦ) who would meet in the Wókheya (council tent, ᐓᐠᐦᐁᔭ); a process that would be mirrored in the growing settlement with additional advisory roles for the resident faithkeepers and other important figures. Line about akíčhita (law enforcement).

By 947 CE Mniwa was founded as the second permanent settlement and in 963 CE Oskopa followed, growing in similar paths of settlement to Wokheya. While the stretch of time between the formation of these two cities was rather quick, it took at least another century before more of the tribes began to more widely adopt sedentary life, and some tribes continued to prefer migratory life up to the Asherionic wars. The formation of Wangca (Wáŋča,ᐘᐣᒐ) to the West of what is today Walgroinzin in 1033 CE proved itself another pivotal-point, as it marked the beginning of irregular trade with the tribes of what is now Western Awasin and Wazheganon. It was through this trade that an early relationship began to develop between these regions, allowing for the sharing of ideas and early exchanges of technologies. It is believed this was through this trade that Haratago nomads came to briefly discover Mniohuta around 1200 CE amidst travel through the region en route to what is today Elatia and Enyama. Legends of the peaceful nature of this encounter generally provided a strong basis for amicable relations with visitng fur trappers and later still the Fretrekeriners when they arrived in the 1700s; but, also served as something of a warning of ill-omens as a series of previously unknown foreign diseases swept through the region and led to population declines in most of the major settlements.

As settlements continued to develop and progress, unique styles inspired by traditional structures, such as the Thiyúktaŋ (brick dome, ᖨᐩuᑕᐣᐨ) which was based on the shape of tipis and was sturdier in harsher weather, began to see wider construction. While Earthen lodges such as the Makȟá-thípi (ᒪᐠᐦᐊ-ᖨᐱ) remained in frequent use for important structures such as the Wókheya, traditional meeting halls, and particularly large families, above-ground houses and other such structures began to take greater precedence for residential life as underground spaces were consumed by food storage or used for burial of family members. It was at this point that new types of structures such as the Wakhyuná (sharing lodge, ᐘᐠᐦᐩᓇ) were introduced in order to provide for the entire community, with multiple Wakhyuná being scattered across cities. To manage these Wakhyunás, lower level versions of the camp-council were elected by households who benefitted from the structures and would be charged with managing distribution and deciding how much food was needed at any given time to maintain stockpiles. Typically, faithkeepers would also establish the residences and build shrines and other religious facilities near these structures as a means to ward off thieves or dissuade raiders from hitting stockpiles. While not contributing to these structures was not necessarily a punishable offense, it was considered a moral and spiritual obligation for the sake of one'sThiyóšpaye and standing within a community, so only those who were faced with disabilities or had another role in the community avoided contributing.

By 1100, city-states had become a plains-wide phenomenon, with a majority of the tribes and their major bands joining existing settlements or forming their own smaller communities connected by trade, kinship, or diplomacy. More advanced forms of traditional agriculture were developed to meet the demands of growing populations while the first schools would open to deal with new fields of study such as astronomy, philosophy, military theory, and development. What is now known as the University of Wokheya was, at its founding in 1184, simply a lodge founded by Tȟaté Wóksape (Blowing Wisdom, ᖬᑌᐁ ᐕᐠᓴᐯ), a Khowakotan philosopher whos political ideals centered largely on peace theory and diplomacy driven by Wakanist traditions and is an important author in studies of Mniohutan international diplomatic theory. This proved a model that was followed in other cities with similar institutions and contributing to a plains-wide network of early academics and philosophers.

With the introduction of gun-powder through trade in the 1500s and 1600s, military theory began to shift to accommodate the new weapons which in turn lead to the expansion of growing academic institutions. With the rise of a Llachache gunpowder empire around the same time, cities in the Western plains and along the Wiyopeyata peninsula began to pay tribute to the new empire in exchange for protection. The Hinhanata and other tribes were not willing to make similar concessions and were far enough away to refuse demands of tribute. As a result, the Tonoyangka tended to align themselves with the Evohone and Awa'sipowa of modern day Awasin, while the Hinhanata formed a minor empire of their own, demanding tribute from the triple alliance to the north and clashing with Llahache in skirmishes in the West and minor fighting with Kahnawà꞉ke to the far South. The Hohekoyata were generally left to their own devices by the Oskopa based empire on account of their role as keepers of Mount Hanshke, but Eastern bands were still often forced to pay tribute and would sometimes be forced to take up arms on the side of the Hinhanata.

By 1700, the Hinhanata had resolved to scale back raids as the overwhelming threat from the Llahache was reduced as their power in the region began to wane. This did not, however, end the rivalry that had begun to form between Eastern and Western tribes which would preoccupy conflicts over the coming century. An alliance between the Khowakota, Wiyohutacota, Iyothata managed to keep the idea of all out war on the part of the Hinhanata off the table, though a series of skirmishes and on occasion mourning wars kept the city-states and tribes of the central plains distracted. It was during this time that the Waziyata of the North would encounter Garrelt Miedema and their Fretrekeriner followers in the North in 1751. After forming the initial settlement of Bergpas in what is today Walgroinzin, the Fretrekeriners quickly began to learn and adapt from their new neighbours. Following a particularly harsh winter, the Waziyata had come to the aid of their new neighbours, resulting in the Fretrekeriners signing what was called the Treaty of Friendship which outlined principles of land stewardship on the part of the settlers and equal terms of trade and mutual aid during times of crisis.

It was around this time that, on a vision quest with several of the men from a nearby tribe, that Garrelt Miedema was bestowed with the knowledge that they were a Wíŋkte (ᐏᐣᐟᑫ) and announced a number of theological changes which received mixed reactions from the settlers. This eventually lead to a split between what would become the Universalist Fretrekeriners and the Traditionalists, the latter of whom would continue sailing East while the former remained in Walgroinzin. Having consolidated their rule, Tênaxixti (True Ally, ᑌᓇᐨᓯᐨᐢᑎ, formerly Garrelt Miedema) laid out the plans for a grander city that would attract the nearby tribes and accomplish their vision for a state united in their ideal of comradery and shared inner light. Considerable progress was made on the building of the city by the time of their death, with many of the notable landmarks of the modern city either in construction or completed.

Asherionic Wars

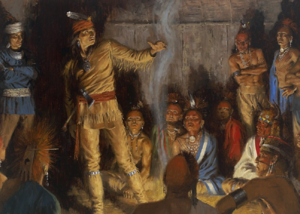

Around the Summer solstice of 1811, at the tail end of one of the annual Sun Dance ceremonies, Asherion and a considerable dispatch of soldiers arrived from the North in order to win over support from the ruling chiefs for the cause of Greater Norumbia. Wanatho, who was the elected Chief of the Khowakota at the time, had long been trading letters with the founder of the Thunder Dance movement Hoshuwiga Krai in the hopes of bringing the Thituwan into the movement. Worried by the potential of encroachment by far less benevolent settlers than the Fretrekeriners that had arrived a half-century earlier, he hoped Asherion's arrival would unify the tribes and shift the region towards Wanatho's goal of a single Mniohutan state either independent or under the banner of Greater Norumbia. The reception was mixed, the show of force by Asherion being seen as something of a sign of aggression at a ceremony that was typically considered a neutral and otherwise sacred ground. Others welcomed the leader and his detachment with gifts and a number of scattered feasts hosted by various Chiefs hoping to win the famed General's favor, seeing his arrival as the potential start for a period of change. Mniohutan Chiefs debated the issue for days following Asherion's arrival, with the Hazirat'e man sitting in on the meeting attempting to win the tribes over through more pragmatic and diplomatic means. Disagreements between the historical rivals of the Hinhanata who did not trust the input of an outsider, regardless of whether he was still part of their broader indigenous family, and the Khowakota who had grown considerably more irredentist and pan-indigenous politically, put negotiations on at a standstill as their various tribal allies drifted towards their historical political bubbles. If not for the fact that negotiations were being held at Mount Hanshke and Asherion's presence, negotiations could very well have gone sour as the mood tensed because of the ongoing disagreements.

Around a week and a half after negotiations began, an army from the Llahache state of Tlåtåw had begun marching from the West in order to try to catch Asherion by surprise. In the process they had terrorised a number of Iyothata communities, in one instance even burning down a village that had attempted to turn them away. Apaled by the news, the Chiefs put negotiations on pause and troops were rallied from all tribes and bands that were present in order to support Asherion's army against the approaching invaders. Allowing the famed general to take command of the allied force, the party of Llahache were overwhelmingly routed at the Battle of Patkasa Wapka with minimal casualties. At the conclusion of the battle, negotiations were resumed and quickly wrapped up, with all Chiefs present impressed by Asherion's considerable skill and pledging loyalty to his cause. Not soon after the events of the negotiations were delegates from Greater Norumbia sent in order to organise administrative regions for elections for representatives to the Federative Assembly.

Certain bands put up varying degrees of resistance upon the arrival of these delegates, seeing their line-drawing as intrusive despite the lack of any actual enforcement of the boundaries. A number of minor rebellions were forcibly put down, most notably one led by a Kahnawà꞉ke-Hohekoyata man named Kaientaronkwen (Gathering the Goods, ᑲᐃᐁᐣᑕᕒᐅᐣᑵᐣ), who saw Asherion as no better than the Belisarians with the occupation of Serkonos. He would go on to lead a bloody year long campaign until his death at the Battle of Wanabe at the hands of local militias led by the Hinhanata general Iluuhachke (He who stands tall, ᐃᓬᐆᐦᐋᐨᐦᑫ). While the Fretrekeriners were generally indifferent to Greater Norumbia, already fairly in-line with the Asherionic ideals for practicing Christians, attempts at drafting them for the army even into auxillary roles were often met with collective civil resistance. Despite the varying degrees of push back, the beginnings of what would become the eventual borders for the modern Mniohutan state were drawn. The community councils integrated elsewhere within Greater Norumbia meshed well with traditional democratic systems of governance in the various urban centers scattered across the basin, laying the foundation for the eventual consulate system used by the modern state. The ease of shift allowed for faster mobilisation, with forces being drawn from across the plain as part of a broader recruitment effort on the part of local chiefs and Asherion's representatives.

Generals such as Iluuhachke, as well as the Wiyohutakotan general Hupahusa (Red wing, ᐦᐆᐸᐦuᐢᓴ) made a name for themselves both domestically and on the front lines as Norumbian forces continued to push South and West. Iluuhachke was notorious particularly amongst the Llahache, who he had little regard for, burning numerous towns and villages in a push towards the Makrian Ocean in the Burning Cactus Campaign. While his scorched-earth policy was controversial, its success in pushing the front West at the speed it did made him a major hero amongst the Hinhanata. Likewise, general Hupahusa was renown for his victory at the Battle of Łichíiʼii in which a number of well executed cavalry charges managed to dislodge an armed force dispatched by coalition forces from Igahi and Tlåtåw. His successes on top of the respect from those he occupied won him wide admiration, enough so that he would later be called south for the invasion of Belfras in 1817, ultimately dying in battle in 1822 several months before Asherion's first capture. The Khowakotan sailor Wachíwiní (Woman Who Dances With Water, ᐘᐨᐦᐃᐏᓂ) was also famed for her role in The Battle of Wokheya in which coalition forces from Dzillbesh attempted a naval invasion on the regional capital and were defeated thanks to her creative use of traditional fishing vessels and armaments from the nearby fort. Militias would spring up along the Hinapa Sea following her victory which employed similar methods for rapid response, methods that would continue to see use to the modern day.

The Council of Eight Lodges

In the immediate aftermath of Asherion's first capture, Mniohuti officials progressively became more paranoid about the possibility of being divided by Belisarian powers with the looming collapse of the Federation of Great Norumbia. Wanatho addressed letters to each of the major Thituwan Chiefs and communal authorities on the prospect of the meeting of a common congress for the formation of a greater Mniohutan state, a concept that would have been largely unfathomable a mere decade prior, but was quickly and almost universally positively received. Letters of agreement poured in from nearly every tribe, band, and community that had been invited and in April of 1822 the congress was convened in Wokheya to agree on the principles of a potential national entity.

It was first determined that much like the Asherionic Federation from which it sprung, the Mniohutan state would need a central figure to guide the nation in its formative years and be its spiritual and revolutionary backbone, perceived more literally by the Thituwan peoples this paved the way for the creation of the role of High Chief of Mniohuta. In order to ensure that this figure would not usurp power and undermine the revolution, a Council of Elders with representatives from each of the Bands in the Confederation was formed in order to act as oversight and to advise the High Chief in any decisions he made. Elements of a broader interconnected democratic apparatus were also incorporated into this new system, utilising preexisting communalist democratic infrastructure that had been used by the tribes historically, and incorporating the wider nested councils (conclaves) instituted under Great Norumbia. Each level of what would become the conclave system had varying powers, giving people authority to make decisions from the local level all the way up to the national level through a system of consensus and representation.

The Articles of Confederation drawn up by what became known as the Council of Eight lodges were signed by each of the eight tribes of the plains, and on April 14th 1822 the Confederation of Mniohuta was formally declared. It became clear from the onset that the Waziyata and Fretrekeriners to the North would be pressured into forming their own Republic as the Western front began to dissolve, seeking protection as their former allies seemingly showed their weakness. This led to a rather immediate strained relationship between the two newly formed states, with representatives from both nations immediately disagreeing over what constituted national boundaries at the Congress of Thessalona. Ultimately, the Belisarians settled the dispute by drawing a line through the Wazepiya mountains and along the Tchoutacabouffa river which contributed to the early uneasy peace between the two states.

In the ensuing decade intermittent skirmishes would ensue as a result of land disputes and attempts at enforcement of boundaries along the newly drawn border, leading to a number of minor military confrontations initiated by local militias and other regional actors. This initially proved something of a diplomatic nightmare as both sides scrambled to keep their people in check, but also proved a moment of unity as both governments attempted to work in tandem to bring stability to the new border. This led to a gradual warming of relations which in turn paved the way for the gradual decline of land disputes and the beginning of early talks of unification between Mniohuta and Waziyand.

The Constitution of Friendship and Industrialization

Minister-Presidint

Wičháša-Itȟáŋčhaŋ

As infrastructure between the two states continued to interlink, popular support for the unification of Waziyand and Mniohuta continued to build, particularly amongst the indigenous Waziyata of Waziyand. While there was a degree of scepticism on the part of the Fretrekeriners, the continued good will between indigenous groups and settlers through the duration of the Asherionic wars eased contentions that manifested elsewhere on the continent with the conclusion of the war. In 1844, Waziyand Prime Minister Johannes Frijheid met with the 2nd Mniohutan High Chief Wakíŋyaŋ Okínihaŋ (Great Thunder, ᐘᑭᐣᐨᔭᐣᐨ ᐅᑭᓂᐦᐊᐣᐨ) in Capastat to open negotiations for a hypothetical unification between the two states. Many of the wartime reforms made by Great Norumbia had been maintained or built upon in Waziyand, with nested councils also forming the base of their republic and principles of indigenous communalism carrying into the settler state, albeit with less of a lean on Asherionic principles than its Southern neighbor.

One of the primary demands that was made was a call for a new constitution: one that, while still Asherionic and indigenous at its core, would reduce the power of the High Chief and put more power into the hands of the Conclave of the People and labour unions. While this was met with some push back by Okinihan, he would come to accept these terms provided that reduction of his authority would be gradual so that he could continue oversight of the growth of national development. On top of these reforms, Johannes also requested a recognition of a list of citizens rights within this new constitution; something that had largely been left absent in the articls of confederation, as rights had been pre-assumed by the original writers. Together, the two leaders along with an attache of diplomats worked on a list of rights to be considered human rights that should be afforded to all men in the newly unified state, among which were rights of beneficiaries, more specific civil and political rights, individual and group rights, and other groups of rights covered under economic, social and cultural rights.

With the conclusion of the meeting, both leaders set into motion what would become a two year transition as both states prepared to merge into one entity. The proposed constitution would undergo a number of reforms, including the addition of further human rights and other articles to ensure the stability of the Mniohuti political sphere and preservation of democratic principles. As a result, the updating of the articles of confederation into a new constitution would be a several decade affair that would stretch far past the unificiation of both states. In 1846 Johannes and Okinihan met in Walgroinzin, the capital of Waziyand and the 2nd largest city in what would be Mniohuta at that time, for a formal signing of a treaty of unification to much fan fair. The ceremony ultimately lasted a week, with nation-wide celebrations being concluded with the passing of a ceremonial pipe between the two leaders and a number of other bureaucrats who had been involved with the transition.

In the following years, the first industrial mills would begin to open in the north and rapidly spread towards central and southern Mniohuta along its many major rivers as the industrial revolution crept West from Wazheganon and Gristol-Serkanos. Great efforts were made by local officials and labour organisers to ensure that workers were organised and given fair hours and treatment in these new facilities as society began to adjust to this new mode of life. Urban centers began to grow considerably, leading to the development of further social housing and other necessary accommodations to deal with the slow but steady flood of new arrivals in Mniohuta's cities and major towns. Great strides were also taken in order to reduce the quickly realised ecological impacts of these new factories to what extent the times permitted, using traditional methods learned during the Years of Ash to sort out polluted water and working vegetation and "micro forests" into urban settings to improve air quality.

Along the Southern border with Gristol-Serkanos, brewing ethnic tension created by the solidifying of the historically porous border between the two states led to a brewing powderkeg. In May of 1863, workers of the Miners Union of Anu Katha Ipa began a copper mining operation outside Amisk and were not soon after harassed by a local Serkonian militia who claimed they were illegally mining on Serkonian land. The dispute quickly exploded into a proper skirmish, with miners arming themselves and defending the mountain while more Serkonian militias arrived and began shelling the mountain in what became known as the Battle of Mount Anu. This expanded into the Second Osawanon War as militias from the Mniohutan consulates of Wospibitha and Giciyahe met Serkonian forces in the Osawanon mountains as news of the conflict continued to spread. Initial gains on both sides were for naught as the conflict drew to a bloody standstill; with the conflict remaining contained in the mountains as a result of technological and tactical differences that kept both parties at bay. The war would continue until 1875 when forces deployed from Pontiac-Bernadotte from the Royal Gristo-Serkonan Armed Forces arrived on the frontline, prompting Mniohuta to sue for peace and leading to an uneasy status quo ante bellum with borders being formally recognised along the frontlines at the close of the war.

Amidst the conflict, further industrial technology was introduced to the region including, most popularly railways which allowed Mniohuta to move ammunition and foodstuffs to the front lines faster and facilitating greater cooperation with its Asherionic allies. In that spirit, Wazheganon completed a railway from Chugara to Chunkaske (the "Chu Line") in 1870, which further supplied the frontlines and furthered cooperation between the two indigenous states. Likewise, the National Postal Union continued to play a pivotal role in national politics, lobbying for further involvement in regional conclaves in order to secure the mines north of the Osawanons for industrial acquisition to feed the growing network of telegraphs and railroads supported by the Union. The most important change during the war also came with the formal passing of the Constitution of Friendship in 1865, sped up as a result of the conflict in order to ensure that the national people's conclave could play a larger role in managing foreign affairs and ensuring that negotiation is an option before war is considered.

In the aftermath of the war, a nation paranoid of settler neighbours infringing on their sovereignty drove Mniohuta into a military buildup involving the purchasing of updated arms, standardisation of uniforms, and the formation of proper military branches and mechanisms to direct consulate bound militias. This drew much criticism from peace advocates, particularly wakanist clergy, fretrekeriner groups, and scholarly salons who pointed to peaceful alternatives that could have been attained at the start of the previous war had the government had a better grip on diplomatic affairs. To placate these groups, considerable work was done to expand the understaffed and generally neglected Bureau of Friendship and Peace which had been focusing its few resources on building relations with its other communalist neighbors to the north since unification with Waziyand. Outside of beaurocratic expansion, labour unions continued to gain power through industrialization, particularly the Federation of Industrial Workers, Federation of Miners Unions and the National Rail Union. The expansion of the salon system also followed informally, with greater democratic participation leading to people forming salons in order to lobby regional and national conclaves on specific issues and areas of interest.

The Wiyohpeyata Peninsula War

As the country progressed into the 20th century, major changes including further industrialization and wider electrification greatly impacted the fabric of Mniohuti society. Government and consulate entities worked to provide make-work programs, redistribute resources and wealth, and promote unions and workers cooperatives in order to stimulate economic growth. The popularity of railroad networks because of their general efficiency and because of pro-rail informational campaigns put out by the National Rail Union led to heavy investment in rail from its inception. The National Postal Union was also one of the most efficient mail carriers in Norumbia, often passing parcels in a matter of days. This easier spread of people and information led to the gradual growth of Numenist elements on the Wiyopeyata peninsula, with the comparably underpopulated and under served area proving an ideal space for Numenist evangelism. As the 1920s began to turn to the 1930s, general discontent raised by slow growth in the consulates of Wiyohpeyata and the Western portion of Waziyand paired with Mniohutan support of Wazheganon in the Fourth Osawanon War led to a number of demonstrations which were exploited by Numenist clergy in Mniohuta.

While Mniohutan national bureaus attempted to remedy issues on the peninsula, a cargo train derailment outside of Wokcan in 1932 followed by a fiery sermon by a Numenist priest led to riots in the city which required the deployment of local militias and a nearby naval garrison to end the violence. Armed civilians who had been partaking in the riot fired on the forces deployed to quell the violence, with the situation quickly spiraling out control as calls for annexation by Elatia or Wiyohpeyatan independence was fueled by religious fervor. Wakanist practitioners who tended to be more pro-Mniohuta began to form their own militias in reaction, often performing terroristic attacks on Numenist places of worship and communities which in turn led to reprisals by the Numenist militias.

News of the growing sectarian violence quickly spread across the country, and early into the New Year of 1933 the People's Conclave voted to declare martial law on the peninsula in order to prevent the spread of any further violence. Mniohutan forces arrived in the area not soon after, occupying Numenist and to a lesser extent Wakanist communities and urban centers, with the armed forces responding to violence with immediate action and often times prosecuting people who were uninvolved with rushed trials that tended to favor Wakanist elements in the area. This was seen by practitioners of Numenism as evidence that their upheaval was justified, and by the Summer demonstrations and violence had only grown worse, with Numenist militias engaging in a protracted guerilla campaign against Mniohutan forces. With the situation only continuing to spiral and the Mniohutan government doing little to remedy the issue, the Elatian military to the West began a buildup for a hypothetical intervention in the crisis in defense of the Numenist groups in order to force action. Not soon after, the Supreme Prophet ordered forces to cross the Hinapa Strait to aid Numenist elements in Mniohuta, with the first troops making landings on June 6th 1934 and quickly advancing upon the largely unprepared militias in Wokcan, Horatamumake, and Matonumake along the Northwestern coast of the peninsula.

The Mniohutan response was disjointed at first, with local militias rushing to meet Elatian forces at the frontlines while the de-centralized armed forces scrambled to mobilize to meet the Numenists at the front. By July the Elatians had made considerable headway down the peninsula, with the newly formed Mniohutan air force putting up a feeble defense against the overwhelmingly superior aerial units coming from the East. Ironically, one of the first major victories was achieved in the air, with a group of fighters from the 12th Aerial People's Unit (Also known as the Watȟóglašúŋka unit (Wild Dogs, ᐘᖪᐨᐠᓬᐊᐢᓲᐣᐨᑲ)) intercepted a fleet of bombers en route to strategic targets just shy of the peninsula, giving a much needed morale boost. By the dawn of 1935 Mniohuta had fully mobilized and had halted Elatian advances in the Wazepiya range, with most major industrial unions and syndicates shifting towards wartime production in line with emergency measures agreed to by the Sitting Council and combined efforts instituted by military authorities in each of the conclaves. Using techniques learned from the Second Osawanon War, the conflict drew to a standstill along the range, with little headway being made by either side from 1935-1937 as Mniohuta hoped to grind down Elatian morale.

By 1938 repeated bombings across the Southern portion of Mniohuta brought on by Elatian aerial superiority began to grind down the nation's industrial drive and in turn morale, with technological breakthroughs aiding in further Elatian pushes that led to a breakdown of the front line. Despite the best efforts of Mniohutan forces, a series of encirclements secured further Elatian victories and in January of 1939 Elatia offered a cease fire which the government in Wokheya was quick to accept, with the front line settling just shy of the border of the consulate of Wiyohpeyata with its neighboring consulates. Negotiations were tense, with the situation on the border not much better as regular skirmishes broke out between the opposing units which was only urged on further by rival paramilitaries that had aligned with their relevant forces. In August of 1939 negotiations broke down, with the over-confident generals on the Mniohutan side believing they'd devised a plan to push Elatia out and force a surrender. The Southern Rush showed promise at first, with the flood of mechanized vehicles overwhelming forces in the South, sweeping along the coast nearly to the Hinapa strait. This unfortunately came at the expense of parts of the consulate of Waziyand, but this was a calculated risk with the plan to sweep up to the strait and prevent any further reinforcements. By October, hopes of encircling Elatian forces were dashed with losses along the Southern front and losses in the North only growing worse.

Seeing no other option, the People's Assembly voted to sue for peace and by 1940 Elatia had consolidated its gains in order to ensure there was not a repeat of the previous campaign. Wiyohpeyata voted through referendum to be annexed into Elatia, with the added portions of Waziyand being incorporated as well. Wakanists had generally boycotted the referendum, viewing it as illegitimate and rigged by Elatian authorities. In Mniohuta, major reform efforts were made on the part of the military, with the loss being seen as testament of needed change and further investment. One of the biggest outcomes was the shift away from the dominance of militias towards the development of a proper national military with a more developed structure. Likewise, greater investment was set into individual branches, with the air force in particular receiving a number of boosts during the war and facing further expansion in the wake of the nation's loss.

Mniohuta-Elatian Cold War

Contemporary History

Government and politics

Tȟuŋkášilayapi

Iyótaŋačá

Mniohuta is a federal, libertarian socialist consensus democracy in the communalist tradition. Unlike other Asherionic states in the region, Mniohuta has a codified constitution central to its politics. The document enumerates power to nearly each layer of the political system and establishes a list of rights based on the idea of human rights. The country is divided into eleven Consulates, which act less like provinces and more as regional forums to aid in the development of infrastructure and to elect representative to the People's Conclave in Wokheya. During times of war these Consulates are utilised by a management authority composed of civilian and military officials entrusted with control of emergency supply re-distribution and rationing if circumstances become so dire as to require their use. Nested and municipal conclaves are left open enough to interpretation by the constitution so long as they abide by the basic tennants and rights laid out by the constitution, allowing for a broad range of smaller political and economic systems including democratic councils of (mostly) scholars at Universities, traditional indigenous hereditary councils, Fretrekeriner meetings, among a wide range of other potential means of democratic works.

At the national level the constitution grants power to the Conclave of the Confederacy which on paper is a bicameral legislature but is functionally a unicameral legislature, with the lion's share of power sitting with the lower house, the Conclave of the People. The lower house operates on a delegate model of representation and consists of up to 550 members which fluctuates with changes in population or following a popular referendum to expand the Conclave. Members of the Conclave of the People are typically elected by representatives at Regional Conclaves, but are occasionally elected directly by municipal or conclaves as a result of under-representation in a particular area. Special committees exist in order to determine areas which are underrepresented, particularly in terms of minority groups which has become increasingly important in melting pot consulates such as Walgroinzin which have garnered a more diverse population as a result of immigration and asylum seekers. Likewise, advisors are elected by special interest groups to speak on certain issues such as the environment, religious issues, women's rights, labor rights, and other topics of particular importance in order to better inform discussion and debate. The Conclave elects a Tȟuŋkášilayapi (translated into Anglic as premier) who acts as an overseer of debate and represents the nation abroad in a similar role to a prime minister; though lacking the ability to form a cabinet, with the equivalent of a cabinet being composed of syndicate and bureau leaders elected by members of those bodies.

The older of the two Conclaves and the upper house of the Confederacy is the Council of Elders, consisting of up to 150 members representing the major clans and bands of the Thituwan tribes. Elders are elected by members of their kinship networks to represent them and often serve in terms that are limited only by death unless otherwise recalled by their family or are ejected by a majority of the council. One of the main purposes of the council is to act as an advisory body to the Iyótaŋačá (translated as Great Chief), the life-elected head of the Conclave who serves as a spiritual leader of the nation and historically played a key role in Mniohuti politics. The council also oversees resolutions and legislation that is to be passed by the Conclave of the people, with the Great Chief acting as their representative in the main chamber to provide advise on potential changes or impacts and speak to any reservations they may have. In theory the Council of the Elders would also vote on these issues, but following reforms brought about by the Unification Constitution leave the body largely as a rubber stamp for anything passed by the lower conclave.

Outside of the frame of the Conclaves is the Sitting Council, a body composed of the Tȟuŋkášilayapi and elected members of the various bureaus, syndicates, and unions that maintain infrastructure and state security in Mniohuta. While having little in the way of power as a political body, it serves as a forum for national governance and coordination between different parts of the Mniohutan political, security, and economic spheres. Traditionally the Council would meet once a month in order to provide updates on progress made in various sectors that would be delivered in a monthly report to the Conclave of the People, but in 1998 this was changed to a bi-weekly meeting in order to ensure efficiency and transparency. Likewise, it is through this council that updates on pending legislation from the People's Conclave or lower nested conclaves can be delivered to affected parties and provide the opportunity for broader planning or objections to be made that can be passed onto the Tȟuŋkášilayapi.

Political parties as they are understood in other countries do not exist, with Thiyóthipi or councils that are equivalent to Tyresian salons acting in their stead alongside syndicates and unions as loose political affiliations to advocate for particular political ideals and movements. The council system is one of the oldest forms of political representation in Mniohuta, with its origin coming from philosophical and scholarly schools in pre-Asherionic Wokheya and Oskopa which would lobby for particular political issues to Chiefs and tribal councils. In the modern era, citizens and intelligentsia are often apart of multiple councils, with these councils often forming temporary alliances in order to raise funds, lobby, or support certain political efforts or delegates they find agreeable. As is tradition, certain councils act as forums for debate, with the Tȟaokšíwayáwa Tȟaté Wóksape (The Children of Blowing Wisdom, ᖬᐅᐠᓰᐘᔮᐘ ᖬᑌ ᐕᐠᓴᐯ) being the oldest of these councils to continually operate since its founding in 1189. Because the Mniohutan political system is largely driven by a culture of compulsory participation, councils tend to be the easiest means for politically active citizens to garner support for delegateship at higher conclaves.

The National Lodge in Wokheya is the meeting place of the People's Conclave as well as the Sitting Council.

The Elders Lodge is the meeting place of the Council of Elders, located in the heart of Wokheya.

Members of the Asherionic Council of Indigenous Emancipation at their yearly fundraiser gathering in Kanze.

Law

The Mniohutan legal system is scattered with elements of Asherionic law, Tyrrslyndic law, socialist law, and elements of traditional tribal law which are hybridized into a codified system of common law. Likewise, elements of customary law are present regionally due to longstanding traditions upheld by various tribes and bands. At the local level, customary courts or Howóyasu utilize peacemaking circles composed of up to six members of the community elected by municiple conclaves to 2.5 year terms. These courts tend to deal with minor infractions and neighborly disputes, with more serious criminal behavior going to the higher level Hoikhíyela neighbors' courts which are composed of four citizen jurists elected to 2.5 year terms by their local conclaves and presided over by a trained jurist serving a 5-year term appointed by the municiple conclave. The Hoikhíyela courts lead upwards to the Homakȟópašpe or Regional Courts which are composed of up to four trained jurists appointed by conclaves at the consulate level. At the national level, the Howókáǧa or peacemaking court, serves as the court of last resort and is largely modelled after the Wazhenaby courts of the same name, with seven judges being selected by the Council of Elders and formally elected by the People's Court to serve for 20 year terms. Typically, in cases where issues where customary law (which can occasionally be utilized in Howóyasu court) clashes with codified common law, customary law can supersede that which is codified provided it does not infringe on the rights and interests of the people, a matter that if brought into question can be resolved by a Homakȟópašpe court.

Policing as an institution finds its roots in traditional warrior societies which, prior to the city-state era, would act as a 'camp police' in the winter and at other times that it was perceived required firmer societal structure. These akíčhita (peace officers, ᐊᑭᐨᐦᐃᑕ) and their warrior societies would later inspire the Wičhakíčhita (Local Peacemaking Force, ᐏᐨᐦᐊᑭᐨᐦᐃᑕ) that forms the base of the modern policing system. Each wičhakíčhita is usually assigned precincts by municiple committees that meet every 5 or so years to re-evaluate these jurisdictions. Akíčhita are typically recruited from specific communities within that municipality after certification of the completion of a three-year training program, covering all manner of topics from de-escalation to crisis management. Wičhakíčhita tend to also have specialized units such as Wičhakíčhita, or caretaker officers, who are specialized in dealing with specific crises and are often staffed by both professionals and volunteers. Other branch organizations under the authority of these precincts can include fire departments, criminal investigation specialists, dedicated traffic guides, sexual assault response teams, park rangers, domestic violence response specialists, substance abuse or homelessness assistance offices, armed rapid response units, and other more specialized units that are less common.

Typically, akíčhita are given varying levels of armament depending on their rank and jurisdiction, with beat cops typically serving as unarmed peacekeepers, while higher ranking akíčhita are given tasers, pepper spray, or light armaments such as pistols for rapid response to crises. The primary goal of akíčhita is to provide community policing strategies that ensure the community feels that their needs are being addressed, with common strategies often involving the employment of police boxes, and coordination with local communities for the formation of trained neighborhood watches to aid in coordinating emergency response with other departments when necessary. Officers of any position and at any level can be removed from their position if a local conclave finds them unsuitable to serve their communities needs. Likewise, officers can be suspended on a whim or drafted by military officials in times of war in order to organize local militias and peacekeeping forces.