Mirites

Mirite mother and child | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 8,000,000-10,000,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 5,218,441 | |

| 1,839,820 | |

| File:RwizikuruFlag.PNG Rwizikuru | 189,034 |

| 20,918 | |

| Languages | |

| Mirite language (traditional) | |

| Religion | |

| Bahian Brethren Church Continuing Mirite Church | |

The Mirites, sometimes rendered as Mereyits (Mirite: Ⲙⲓⲣⲓⲏⲧ, Miríít), are an ethno-religious group descended from the historical caste of the same name which arose amongst the TBD of present-day Ihram. The Mirites were a nomadic people, eventually becoming a class of warriors and merchants with the adoption of the Hourege system in Bahia in the tenth century. They specialised in financial transactions, due to their adoption of a written alphabet and literary culture as opposed to the oral-based cultures of southern Bahia.

The emergence of the Mirites is directly linked to the adoption of Sotirianity by the Machaï peoples in YEAR. Kartolaos Makianos, the bishop of Anavaen, led his followers on a self-styled "exodus" following their persecution at the hands of the Orthodox religious authorities. They sought refuge amongst the neighbouring fetishist Sâretic entities, where they used their interconnectedness and written language in order to establish a basic banking system. This network eventually spread among the Ndjarendie villages and even further across Bahia. With the emergence of Hourege the Mirites flourished as nomadic merchants and mercenaries, cementing their acceptance amongst the courts of Karanes across Bahia. While some Mirites were involved in anti-colonial resistance movements, the vast majority were accepting of Euclean colonisation and they filled many of the local administrative positions under the new regimes. This led to their villification by many Bahian nationalist movements, with anti-Mirite sentiments growing especially among the Rwizi in Rwizikuru. This led to the community being expelled by the Rwizikuran government in 1966 under Izibongo Ngonidzashe, with the expulsion lasting until 1982, when they were allowed to return. Many fled the country, causing large diasporas in Satucin and Euclea, but also in neighbouring nations.

Etymology

The name Mirite is a Gallicisation of the Classical Machaï word ⲙⲓⲣⲓⲏⲧ, mirieit meaning "new person". This was the name that the first Mirites used to self identify themselves, as a manner of distinction from the other Machaï who they held as not fully embracing the worship of Ezekiel. The name was simplified to "Mirite" by Gaullican missionaries, though Mereyit/Mereïet have also been used in the past. The current spelling was standardised in 1704.

Role

Under Sâre

Due to the highly decentralised nature of Saretic society, the Mirite community was initially separated across several villages. They lived nomadic lifestyles and their literary culture allowed them to pass messages between each other, which meant that villages would often attempt to recruit the Mirites to act as spies in other villages. Merchants would often hire Mirite scribes in order to handle their finances, which attracted a degree of respect and acceptance to the group who were initially considered to be heretics by the fetishist villagers. Constantly on the move and religiously exhorted to be a self-sufficient community, the Mirites were also renowned as warriors and were often hired as mercenaries to defend villages from bandits and other threats.

Under Hourege

It was with the centralisation that Hourege brought to Bahian society that the Mirites were able to fully thrive as a social group. The larger realms that were enabled with the introduction of Rahelian administrative ideas required large numbers of literate and numerically proficient aides and functionaries. The Mirites were highly trusted in this regard, having served in similar roles during the Saretic period. While the Mirite monopoly over literacy was soon undermined by the adoption of the Adlam script for the Ndjarendie language, Mirite scholars and polymaths were regarded highly and often continued to hold dominant positions. With the advent of larger realms and greater trade, a new system was required for the processing of tributes and this led to the adoption of currencies and a rudimentary financial system. Wealthy Mirite merchants began to offer loans to Karanes and even Houreges in order for them to finance their military exploits, and the interconnectedness of the Mirite communities meant that such loans were able to be centralised and noted down. The constant need for soldiers by Houregic states allowed for Mirite men to form companies of mercenaries, who functioned in a manner similar to the loans accorded by Mirite merchants. These factors meant that despite facing the disapproval of large amounts of the clergy and common peoples, the Mirites played a key role in the environment of Bahian society.

During Colonisation

As fellow Sotirians the Mirites were seen as natural partners by the Euclean powers, who needed local administrators who were able to speak the local languages and maintain their authority at a lower level. Many Mirites worked as clerks and in other administrative roles during this period. Their status as Sotirians meant that Mirites faced less persecution under the Euclean administration than they had under the Irfanic and Fetishist Houregic governments which had preceded them, which led to the tacit support of many Mirites for the Eucleans. This role of collaboration, in turn, led to an increase in anti-Mirite sentiment amongst the Irfanic communities who saw it as a betrayal. The Mirite acceptance of Euclean influences led to many going into eastern-style formal education, which led to their exposure to Euclean ideological currents and it was via this ideological connection that ideologies such as Equalism first made their way to Bahia. Many of the early leaders of the Pan-Bahian movement were ethnic Mirites, such as author Daniel Amankose whose essay The Revolt of the Métis is often seen as one of the first signs of a pan-Bahian national identity.

History

Exodus

According to Mirite tradition, the bishop of Anavaen, Kartolaos Makianos, received a vision from Ezekiel that the form of Sotirianity practiced in Anavaen was a "perversion of the ministry of Jesus Sotiras," and that as the sole descendant on the male-line, Makianos was the successor (TBD: ⲇⲓⲁⲧⲟⲭⲟⲥ, diatokhos), or diadoch, to both Jesus Sotiras and Ezekiel Khristo's teachings. Makiano promoted his vision, but was unappreciated by the Sotirians, who began persecuting Kartolaos Makianos and his followers. In response, in 457 CE, Makianos and his followers went on an exodus to the villages in Bahia, as despite their pagan ways, the Bahians would not be hostile to their beliefs. They would ultimately reach Munzwa in 531 CE, with Makianos' grandson, Apamoun I Makianos establishing Munzwa as the seat of the diadochate.

However, according to archaeologists, the generally accepted view is that the Mirites left present-day Ihram around 600 CE, with their arrival in Bahia ranging from around 650 CE and 700 CE. However, it is believed by geneticists that only a small fraction of the Mirite population were ultimately descended from these migrants, with most Mirite ancestors in the Y line, and virtually all in the X line being of local Bahian origin. In addition, there is no evidence showing that the diadoch settled himself in Munzwa until around 1200 CE, when the Rwizi Empire emerged as the main power in eastern Bahia, which has led to controversy as to where the diadochs were initially located after their migration, with most scholars believing that the diadochs were nomadic, like the rest of the Mirites, although some scholars, most notably Geoffrey Chimutengwende, have argued that the Mirite diadochate only established itself around 1200 CE as a separate institution.

Sâretic period

In the Saretic period, the Mirite community splintered, as Mirites spread across Bahia. However, as the Mirite clergy were literate in the Classical Machaï, they were able to send messages between villages, allowing the Mirites to remain informed and to keep track as to when to celebrate their traditional observances. This initially led to poor relations between the Mirites and the native Bahians residing in the villages, although it would improve over time as the Mirites assumed a greater role in Bahian society.

During this period, the diadoch continued to be passed down from father-to-son, while the bedrock of Mirite society was laid: in 703 CE, diadoch Krystafer Makianos decreed that staying in a village longer than seven years was "inherently sinful," as it would lead to sloth, and urged the Mirites to be as self-reliant as possible, so they would be better able to preserve their faith from Bahian influences. The Krystafer Principles also prohibited conversion to the Mirite Church, except "when a master enslaves a non-Mirite," in which case the slave must be converted, and required all men to teach their sons how to read and write the TBD language, so they would be able to communicate with "all Mirites, regardless of where they are."

The adoption of the Krystafer Principles helped ensure that the Mirites remained united, despite their dispersal across Bahia, as their continued nomadic lifestyle and self-reliance allowed them to remain distinct from the surrounding Bahian society, while their growing acceptance by the villages allowed the Mirites to assume a niche as a mercantile and warrior caste.

Bahian consolidation

With the start of the Bahian consolidation against the Founagé Dominion of Heaven in 898 CE, the Mirite community, like the fetishists, were worried about the further incursion of Irfan against the villages that they resided in. In this environment, while villages attempted to form alliances with one another to protect themselves, these alliances frequently collapsed due to mutual suspicions and demands of equality between the villages. However, the Mirites played a role in securing these agreements, and attempted to mediate in disputes, even though these efforts frequently failed to achieve much success.

As a result, with the rise of the houregic system, the Mirites initially feared they would lose their status and prestige, but instead, the Mirites became administrators, as there was a need for people who were literate and who had numeracy skills to help administer these newfound states. This not only allowed them to maintain their positions in society, but also play an important role in the fledgling trade networks between the houregic states and the rest of Coius.

With the establishment of the Rwizi Empire around 1160 CE, the first authentic records show the presence of a diadoch in Munzwa, which was the empire's capital. These records, penned by diadoch Tawadros III Makaios around 1166, said that "the diadoch and his family have an obligation to stay in Munzwa" in order to protect and promote the interests of the Mirite caste in the empire.

However, even in the thirteenth century, many clergymen complained of the Mirites adopting the "vulgar language" spoken by the other castes, suggesting the start of a language shift from the Classical Machaï to the local Oulume languages, such as Rwizi, with the first evidence of literary records written in Rwizi, known as khameos (ⲭⲁⲙⲉⲟⲥ, lit. commoner) dating to around 1250 CE.

By the time of the fourteenth century, diadoch Sarabion I Makaios restated the Krystafer Principles, and condemned "many of our men for failing to teach their sons how to speak our language," with Sarabion complaining that "many of the potential clergymen have little knowledge of how to speak our language, though they know how to read and write its letters in the khameos style."

Bahian golden age

With the beginning of the Bahian Golden Age in the fifteenth century, the position of the Mirites in the houregic system had effectively been cemented across most of the subcontinent. As Bahia's financial system began developing, the Mirite community assumed a position as moneylenders, with Mirite records of transactions greatly increasing during this period. This earned them criticism from the fetishist clergy and the commoners, leading to growing tensions between the clergy and the commoners, and the Mirite community.

With the publication of the Akrivia Nakosmos by Theodoros of Igitare, the Lourale ka Maoube, or the Contestations of the Elders began. During this period, the Mirites contributed extensively to the advancement of science in the region, primarily to the fields of philosophy, theology, and astronomy, with prominent Mirites being Evanderos of TBD, Ksystous of TBD, and Yeshak II Makianos.

In 1491, a schism occurred, as Bishoi Sawiris published a letter criticising the then Diadoch Khristophoros I Makianos, arguing that as Ezekiel went to heaven in 59 CE, it was "fundamentally impossible for Ezekiel to give a vision to Karatalaos Makianos," and that based on the Book of Nod and the Book of Eden, Bishoi Sawiris was the real diadoch. Although this schism was relatively minor, as only around five percent of the Mirite population sided with Sawiris, the Sawirites posed a serious threat to the Mirite faith that Khristophoros I Makianos anathematized Sawiris and excommunicated "all those who follow Sawiris."

Despite this schism, the Mirites were able to maintain their position among the houregic society in Bahia, as the small size of the Sawirite community, combined with the latter's turmoil made it less attractive to many Mirites.

By the sixteenth century, as the golden age began to come to a close, and the fortunes of the Rwizi Empire began declining, the role of the Mirites continued growing, particularly as the Rwizi Empire became dependent on loans from the Mirites. As the Empire was unable to pay them back, mercenaries and funds began to be directed to other houreges and karanes, which while it benefited them, caused the reputation of the Mirites to diminish, particularly among the Rwizi, as they were seen to be duplicitous.

Colonial era

At the start of the seventeenth century, relations between Rwizis and Mirites were deteriorating, particularly as the weakening Rwizi Empire became reliant on the Mirites, much to the chagrin of the military class. With many independent houreges beginning to persecute Mirites, in 1609, Diadoch Ksystous III Makianos ordered "all Mirites conceal their identity" to protect themselves from persecution, invoking the pillar of hnouhôp. However, despite this, many Mirites fled to Makania in present-day Mabifia in order to escape the persecution by the Rwizi states, while others moved closer to the new trading posts set up by Euclean powers, such as Port Graham or Sainte-Germaine.

In 1655, following the sack of the city of Munzwa by the Kambou Empire, Ksystous' son, Awraham VII Makianos and his family were sent to the city of Koupanni by the conquering Kambouan forces, thereby making Koupanni the new centre of the Mirite Church. With the relative tolerance given to the Mirites, Awraham VII was able to rescind his father's order to conceal their identity. Meanwhile, in the newly-established trading posts, Mirites became valued as go-betweens between Euclean officials and native Bahians, due to the Mirites' faith being related to their Sotirian faith.

The growing cooperation between Mirites and the Euclean colonisers gave the Mirites a privileged position in the emerging colonial society, but at the expense of undermining their reputation among the native Bahian population even further. By the turn of the eighteenth century, Mirites have effectively become firm allies of Euclean powers, as they were employed in administrative positions, which allowed them to gain certain privileges that other Bahians did not have.

This meant that when slavery began to be abolished, first by Estmere in 1740, and later by Gaullica in 1790, the Mirite community found themselves vulnerable, particularly as in present-day Rwizikuru, Estmere would abandon Port Graham in 1803. Mirites still living around Port Graham were "slaughtered as though they were dogs" by the native Bahians, with reports to Euclea helping cause the Euclean public to demand that Bahian Fetishism be cracked down upon.

During the Fatougole, as Euclean powers asserted or reasserted control over areas of Bahia, Mirites were once again willing to assist the Euclean colonisers against the native Bahian population. After having helped Eucleans assert control, they helped the Eucleans maintain control over Bahia, which meant that though they were not able to rise to the highest positions in colonial governance, they were able to reach higher levels than most Bahians at the time, and were able to receive a better education than most Bahians.

By the late nineteenth century, Mirite nationalism began developing, with one current being led by Hitimana Bestravos, who advocated for the creation of a Mirite state in present-day Makania based along eastern principles, while another current was led by priest Aron Yassa, who advocated for a Mirite state to be led by the Diadoch. While these two currents were prominent among Mirite intellectuals advocating for independence, there were some who advocated differently, most notably Daniel Amankose, who advocated for Bahian unity. However, virtually all Mirites at the time were willing to cooperate with Euclean authorities, with almost none of them willing to use violence to achieve their goals, leading to many Mirites cooperating with the Eucleans during the Sougoulie.

Thus, as the twentieth century began, the Mirite community occupied privileged positions in not just the colonial governments, but also in the economy, with a report from 1901 reporting that the Mirites in the Estmerish colony of Riziland paid around seventy percent of the colony's taxes despite only making up a small proportion of the country's population. This led to continued tensions between Bahians and Mirites, particularly as the former resented the latter for their betrayal and for their dominance over the economy. At around the turn of the twentieth century, contact with the Brethren Church had been made, leading to a development of close ties between the Brethren Church and the Mirite Church, starting under the leadership of Mirite Diadoch Danyal IV Makianos, and continuing under his successor, Khristophoros II Makianos.

Anticolonial period

As opposition to direct Euclean rule grew across the subcontinent, the Mirites found themselves in a vulnerable position, as due to their cooperation with Euclean powers, the Mirites were distrusted by many Bahian nationalists. This led to increasingly hostile relations between many native Bahian groups and the Mirites, which in turn led to Mirites become more aligned with Euclean colonisers.

However, after the Great War ended, as most Euclean powers began plans to decolonise the continent, the fate of the Mirites became uncertain. With Mabifia falling into a civil war shortly upon its independence in TBD, Diadoch Danyal IV Makianos aligned the church with the karanes, out of fears that the Bahian socialists would "hurt traditional religions" the way that "the colonisers did to the native religion." However, many Mirites living in urban areas, including Léopold Giengs, supported the Popular Liberation Movement.

Despite these efforts, upon the conclusion of the civil war and the establishment of the Mabifian Democratic Republic, the new Diadoch, Khristophoros II Makianos, and his family were forced to leave Koupanni, heading to Port Fitzhubert in 1943. Under Giengs' regime, the Mirite community were treated well, particularly as Giengs himself was a Mirite, with Giengs' successors continuing his policies towards the Mirites. This did lead to a perception among opponents to the Mabifian government that Mirites were promoting socialism, which only heightened the anti-Miritism present among the average Mabifian.

Meanwhile, in Rwizikuru, upon its independence from Estmere in 1946, relations between Mirites and the Rwizikuran government were initially positive, with Zophar Bohannon allowing the Mirite population to maintain their economic position, even as the Rwizikuran government sought to adopt socialist policies. However, relations deteriorated from 1954, when Vudzijena Nhema became the leader of Rwizikuru, with policies being made to rapidly reduce Mirite influence in society, until it culminated in their expulsion from Rwizikuru in 1973.

In the religious sphere, by 1947, full communion was established between the Mirite Church and the Brethren Church, with contact and cooperation between the two sects of Ezekielism increasing. Diadoch Khristophoros II advocated for ecumenism to the Brethren Church, and believed in the "reunification of the two churches." With increasing numbers of Mirites settling outside of Bahia, Khristophoros II ordained bishops and priests to serve the Mirites living in the diaspora.

Modern era

By 1966, the Mirite community in Rwizikuru was expelled by Mambo Izibongo Ngonidzashe, on the pretext that the Mirites had "reaped the profits of oppression, of colonialism, and of [Rwizikuru's] resources." The expulsion order seized all property and businesses owned by Mirites, including churches.

In response, Diadoch Khristophoros II Makianos relocated the Mirite Church to the Satucine city of TBD, with many Rwizikuran Mirites following the Diadoch to Satucin. With the relocation of the Mirite Church to Satucin, it allowed for a deepening of ties with the Brethren Church, culminating in a 1968 agreement where the Brethren Church would become an autonomous Brethren Church under the jurisdiction of the Diadoch of the Brethren Church, but permitting Khristophoros II to maintain his title of Diadoch until his death.

Upon Khristophoros II's death in 1973, a schism took place, as while his eldest son, Yakobas Makianos became the Patriarch of the Bahian Brethren Church, his second son, Apamoun declared himself the Diadoch of the Continuing Mirite Church, taking the name Apamoun V. This schism greatly divided the Mirite community, as many priests and bishops sided with Apamoun V's claim, as they believed that Khristophoros II had no right to cede his title. Apamoun V severed communion with the Brethren Church over the "illegitimate agreement," leading to the Brethren Church cutting communion with the Continuing Mirites.

At the same time as the schism, the Second Mabifian Civil War raged on, with many Mirites in Mabifia supporting the socialist government, as they feared persecution by the rebel forces. However, some anti-socialist Mirites in Makania took the opportunity to wage a war of independence, seeking to create a Mirite state in Makania. This was supported by Continuing Mirite Diadoch Apamoun V, who believed that by supporting them, he would not only be able to return to Koupanni, but also cement the Continuing Mirite Church's position as the legitimate Mirite Church.

This led to the emergence of the Mourâhiline Sans-Éclipses, who defended against the Mirite separatists. Thus, when the Second Mabifian Civil War concluded in 1978, tensions between the Sans-Éclipses and the People's Coalition for Makanian National Sovereignty remained, leading to the outbreak of the Makanian Conflict, which included the left-wing Mirites, who established the Makanian Workers' Army.

In 1981, the new Rwizikuran monarch, Kupakwashe Ngonidzashe rescinded Izibongo's expulsion of the Mirites, and offered Mirites wishing to return to Rwizikuru compensation for their lost properties and wealth. This led to a re-establishment of a Mirite community in Rwizikuru, although its size was not as large as it had been prior to the expulsion of the Mirites in 1966.

However, during the 1980s, attacks by the Sans-Éclipses on Mirites, and retaliatory attacks led to calls for peace efforts. Thus, beginning in 1989, Yakobas Makianos attempted to negotiate peace with the Mabifian government, with the most successful ceasefire in the Makanian Conflict lasting between 1994 and 1997. Following the election of Mahmadou Jolleh-Bande that year, the Makanian Conflict restarted with full intensity, due to Jolleh-Bande's hardline stance on regional autonomy. While Yakobas Makianos deplored the war crimes on "both sides of the conflict," and urged both sides to return to the negotiating table, Apamoun V felt that "as the Mabifian government has no intention of following the rules of war, the Mirites should not have to do so either."

In the late 2000s, a power struggle emerged in the People's Coalition for Makanian National Sovereignty between those who wanted to negotiate with the Mabifian government to establish a federal system that would give the Mirites autonomy, and those who wanted to continue the conflict. While Yakobas Makianos supported the negotiations, Apamoun V was hesitant to support the proposed negotiations. Following the victory of Ahmad Amantose's faction in 2009, the Makian Conflict continued.

In 2012, Diadoch Apamoun V of the Continuing Mirite Church died, and was succeeded by his son, Beniamin IV, who continues to support the People's Coalition for Makanian National Sovereignty.

Demographics

Traditionally, the Mirite population have resided across Bahia, and as of 2019, around six to eight million Mirites live across Bahia, with most of the population primarily living in Mabifia. While the Mabifian region of Makania was historically the main population centre of the Mirite community in Bahia, as of 2018, only around 3,131,065 people, or between 39-52% of the Bahian Mirite population, reside in Makania.

Since the start of Toubacterie, many Mirites have emigrated, particularly to Euclea and to the Asterias. This has led to the establishment of diasporic Mirite communities numbering around two million people, with the largest concentrations of Mirites living outside Bahia located in Satucin, with 750,632 people, in TBD with TBD people, and in TBD, with TBD people.

Genetics

Mirites traditionally practice endogamy, with marriage to a non-Mirite being forbidden per the Krystafer Principles promulgated by Diadoch Krystafer Makianos. However, since the nineteenth century, these restrictions have been relaxed, and it is now acceptable in all but the most conservative Mirite communities for Mirite men to marry non-Mirite women, although their children have to be raised as Mirites, and Mirite women cannot marry non-Mirite men in all but the most liberal Mirite communities.

Despite the endogamy practiced by the Mirite group, and their traditions stating that Mirites originated in Anavaen in present-day Ihram, mitochrondrial DNA has shown that virtually all Mirites have an X chromosome in the L0 haplogroup, with most Mirites having a Y chromosme in the E-M2 haplogroup, associated with native Bahian populations. Only a small fraction of the Mirite population have a Y chromosome in Haplogroup J, which is associated with inhabitants from northwestern Coius (e.g. northern Zorasan, Ihram, and Tsabara). This suggests that most of the Mirite population were descended from Bahians who either converted to Ezekielanism or were enslaved by Mirites.

Languages

The native language of the Mirite people is the Mirite language (Ⲙⲓⲣⲓⲏⲧⲏⲛ, Miríítín), which is a descendant of the Classical Machaï language. Traditionally, the Mirite language is used among ethnic Mirites to communicate with others in the Mirite community, while it is used in the Mirite Church alongside the TBD language, with linguists speculating that TBD was originally spoken by the first Mirites before they adopted the Mirite language. It is generally written in the Mirite alphabet, which is influenced by the TBD alphabet, although since colonization, the Solarian alphabet has been used to write the Mirite language, particularly for secular works.

However, most Mirites are fluent in the local languages of where they reside (e.g. Ndjarendie, Rwizi, and Gaullican), in order to communicate with non-Mirites and those who do not speak their language. In certain regions of the world, it has led to concerns about language shift, particular among those in the Mirite diaspora, with younger generations tending to abandon Mirite in favour of the local language spoken in their area. To counteract this, the Bahian Brethren Church and the Continuing Mirite Church have sought to promote the Mirite language among the diaspora, to varying degrees of success.

It is estimated that around seventy percent of the total Mirite population can speak the Mirite language to some degree, with the highest levels of proficiency in the Mirite language being reported in the Mabifian region of Makania, and the lowest levels in TBD.

Religion

The Mirites follow a form of Sotirianity related to the Brethren Church, called the Mirite Church. Like the Brethren Church, they accept the divinity of both Jesus Sotiras and Ezekiel Khristos, accept the seven pillars, and believe that they are the one true Sotirian church. However, many of their practices have been influenced by fetishism, especially in the regions where they have historically inhabited.

Since 1973, there are two Mirite Churches, with the Bahian Brethren Church being an autonomous brethren church under the Brethren Church, and the Continuing Mirite Church, which has no connection to the Bahian Brethren Church, with both of them claiming to be the Mirite Church.

Unlike most sects of Sotirianity, per the Krystafer Principles, it is nearly impossible for outsiders to convert to the Mirite faith, with the only exception being those enslaved by Mirites, who would convert to the Mirite Church, or since 1923, children adopted by Mirite parents. In practice, the former option has come to be a loophole for those wishing to join the faith, with the convert, after spending years studying the Mirite way, being "enslaved" for a day, so they would become Mirite.

Culture

Art

The artistic tradition of the Mirite people was traditionally divided into two forms: ecclesiastical art (Mirite: ⲉⲓⲟⲡⲉ ⲕⲓⲥⲥⲉⲛⲓⲅⲩ, eiope kissenigu) and popular art (ⲉⲓⲟⲡⲉ ⲁⲇⲉⲙⲣⲓⲏ, eiope ààdèmríí).

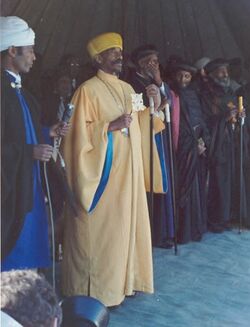

Ecclesiastical art was traditionally associated with the Mirite Church, with paintings, murals, iluminated manuscripts, icons, and crosses. Given the high importance of the Mirite Church among ethnic Mirites, ecclesiastical art was traditionally seen as the most important form of artistic expression among the Mirite community. Thus, many scholarly works have been written about Mirite ecclesiastical art.

Popular art in contrast was associated with textiles, basketry, and jewelry. Unlike ecclesiastical art, popular art was traditionally seen as not being an important form of artistic expression among the Mirite community, to such an extent that until 1974, little work had been done on Mirite popular art, as with the exception of cross necklaces and the robes worn by clergy, it was believed the Mirites had similar forms to those of their Bahian neighbours.

Since the start of Euclean rule over Bahia, both the Mirite ecclesiastical arts and the Mirite popular arts have been influenced by contemporary Euclean styles, to such an extent that nowadays, most Mirite art is done with Euclean styles. In response, both the Bahian Brethren Church and the Continuing Mirite Church have sought to promote the traditional Mirite arts.

Cuisine

Due to the historically nomadic nature of the Mirite people, Mirite cuisine was based on their form of pastoralism. To this end, most of their cuisine involves cow's milk and beef-based products, as Mirites herded cattle. However, Mirites also practice consumption of blood.

Mirites traditionally had two meals: breakfast (Mirite: ⲕⲟⲕⲕⲁⲁⲇ, kokkáad), and dinner (Mirite: ⲕⲁⲃⲁⲣ, kábar). Breakfast is traditionally consumed after the morning milking, while dinner is traditionally consumed after the evening milking. However, in more urban centres, breakfast is usually consumed around 7:00 am, and dinner consumed at around 6:00 pm.

A common staple food among the Mirite community is a beef stew, made with beef and fruits (usually mangoes), and cooked in water. The beef stew is commonly consumed both at breakfast and dinner, alongside a cup of milk. Another common staple food is kabar, which is a flatbread made with ground fenugreek seeds and maize, although kabar is traditionally reserved for the clergy, as it is also used in the eucharist alongside cow's blood.

One of the most popular traditional snack foods among Mirites is a boroso, which is a type of blood sausage made from the meat and blood of a cow, as well as spices and fat. The boroso is traditionally consumed as a snack between mealtimes, and to this end is often not consumed with a beverage.

However, one of the most prominent Mirite foods is tuygu-díís, which is a blood soup made from the blood of a bull, the milk of a cow, and minced beef. Tuygu-díís is traditionally consumed at celebratory events, such as weddings and holidays, such as Irgemi, and is often seen as one of the most important foods among the Mirite community. Tuygu-díís is often consumed with a cup of milk.

Festivals

Traditionally, the Mirite Church used the Mirite calendar, which was a 364-day calendar devised by Krystafer Makianos and based on the seasonal and agricultural patterns in Bahia. Sabbatical years are marked every seven years, with an extra week added to the Mirite calendar, except for every fourth sabbatical year (i.e. every twenty-eight years), when two extra weeks are added to the Mirite calendar. These extra "sabbatical days" are placed at the end of the year. A traditional Mirite day is said to start at sunset (e.g. 1 Harmi-áman, 1564 began at the sunset on 9 May, 2020, not at midnight of 10 May, 2020).

The most important festival is Irgemi (Mirite: Ⲓⲣⲅⲉⲙⲏ, Irgemí), or the Mirite New Year. Irgemi is celebrated on 1 Harmi-áman, which is the first day of the Mirite year (between the last Sunday of April and the second Sunday of May, depending on the year), which marks the beginning of the wet season in modern-day Rwizikuru. On Irgemi, feasts will be held, with traditional Mirite cuisine being consumed on this day. These feasts will involve extended family, and is generally held at the residence of the family patriarch.

The second most important Mirite holiday is Ascension Day (Mirite: Ⲁⲛⲁⲗⲏⲯⲓⲥ, Analípsis), commemorating the day that Ezekiel ascended to heaven. Ascension Day in the Mirite calendar takes place on 11 Árki, or on a day falling between the first Friday following the first Sunday, and the third Thursday of April. On Ascension Day, per the pillar of suloqa, Ascension Day is marked with quiet contemplation, with no work to be done on that day.

Finally, the third most important Mirite holiday is Nativity (Mirite: Ⲩⲛⲛ-ⲓⲏⲥⲩⲥⲓⲁ, Unn-iēsusia), celebrating the birth of Jesus Sotiras, who was the father of Ezekiel Sotiras. Nativity falls on 5 Síiw (between either the last Wednesday of December or first Wednesday of January, and the third Tuesday of January). On Nativity, feasts will be held, although they would not be as lavish as the feasts on Irgemi, while gifts would be exchanged to friends and strangers.

Other important Mirite holidays include the feast day of Saint Kartolaos, which falls on 11 Sóo-márti (between the first Tuesday of October and the third Monday of October), Pasha, which is a movable holiday based on similar calculations to that used in the TBDian calendar (e.g. Pasha falls on 25 Silel-áman, 1563, or 19 April, 2020, but will fall on 8 Harmi-áman, 1565, or 2 May, 2021), and Epiphany, which falls six days after Nativity (i.e. 11 Síiw), and celebrates the baptism of Jesus Sotiras.