User:Costa Fiero/Sandbox

Republic of San Miguel República de San Miguel | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

| Motto: "Unidad, Trabajo, Progreso"(Auratian) "Unity, Work, Progress" | |

| Anthem: Himno de Liberación Anthem of Liberation | |

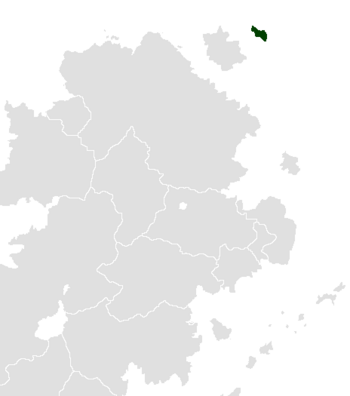

Location of San Miguel in northern Coius | |

| Capital and largest city | Laguira |

| Official languages | Auratian |

| Demonym(s) | San Miguelan |

| Government | Presidential republic |

| Martín Lacasa Carvallo | |

| Guillermo Aparicio de la Cruz | |

| Establishment | |

• Colonisation by Gaullica | January 16, 1422 |

• Colonisation by Auratia | September 18, 1591 |

| February 20, 1820 | |

• Declaration of Independence | September 22, 1927 |

| March 13, 1929 | |

| June 30, 1933 | |

• Independence | October 1, 1936 |

| Area | |

• Total | 26,593 km2 (10,268 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• June 2020 estimate | 3,396,332 |

• 2016 census | 3,346,686 |

• Density | 125.8/km2 (325.8/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | June 2020 estimate |

• Total | $73.03 billion |

• Per capita | $21,824 |

| GDP (nominal) | June 2020 estimate |

• Total | $44.99 billion |

• Per capita | $13,444 |

| Currency | Auro (₳) (SMA) |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (Laguira Standard Time) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+5 (Laguira Summer Time) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | 301 |

| Internet TLD | .sm |

San Miguel, officially the Repulic of San Miguel (Auratian: República de San Miguel), is an island state located in the northwest Vehemens Ocean, sharing martitime borders with the island of x to the east. It is the largest Auratian speaking country outside of Auratia, and has one of the highest standards of living anywhere in Coius.

The island was inhabited by a people refferred to by Auratians as the Guanifrios, meaning "cave people", who survived until the 15th century, when explorers from Euclea began exploring the coasts beyond northern Rahelia, with the island discovered by Weranian explorer Johannes Hossinger, who also discovered and mapped the island of x to the west, and named it Sankt Michael after the patron saint of the military. San Miguel became the first fully mapped island in the Vehemens, and as trade with both Asteria Superior and Bahia increased, the island became contested among different Euclean powers. Eventually the Gaullican Empire established the first Euclean settlement on the island in 1422, with other settlements established elsewhere around the island. However, these settlements would not last, owing to a combination of volcanic activity and famine brought on by the eruption of El Altar in 1432, and subsequent future volcanic eruptions between 1439 and 1444, which also severely affected the Rahelian populations in southern San Miguel.

Eucleans returned to San Miguel in the latter decades of the 15th century, the Gaullicans reestablishing trading ports on the islands alongside the Estmerish and the First Hennish Republic. These ports were small and comparatively underdeveloped until Asterian colonialism began to accelerate, which saw these ports take on the importance of being a stopover on sea journeys between Euclea and the Asterias. These small ports struggled under the continued series of future natural disasters on the islands, and many had to be abandoned due to additional significant volcanic activity on the island. Plagues also became a problem on the island, and significantly impacted both local and Euclean populations.

Auratia began colonisation of San Miguel in 1591, taking over most of the island in short succession, making it one of the first successes of the new Kingdom. Auratia used the island primarily as a means of enabling its ships to trade with the Asterias, as well as eastern Coius, particularly Bahia. Other Euclean colonial powers came to use San Miguel for much of the same purpose, bringing substantial wealth and investment into the island. San Miguel was retained as a part of the new republic in 1820, however, conditions on the island remaind the same as they had done under the Kingdom of Auratia. The island's Euclean inhabitants often enjoyed a superior quality of life to the Auratian mainland, while the mixed and the few remaining native islanders were subject to the economienda system of forced labour as well as indentured servitude on the island's agricultural plantations. This system was maintained by a powerful group of wealthy merchants and landowners known as el poder, whose authority over the island was not challenged until the outbreak of La Lucha in May 1896, which marked the first struggle for the total emancipation of the island's criollo population and the struggle for independence, giving rise to the cult-like reverance for revolutionary figures such as Domenico Céspedes and Bartolomeo Azcárraga. However, it remained in Auratian hands but with significant concessions made by the government in Cienflores, including democratic and social reforms. This period of social and democratic governance lasted until the takeover by the September Clan in September 1927. Unwilling to accept the dictatorship installed in Cienflores, the country rebelled against the military junta and declared independence, which was not recognised until 1937. During the Great War, the island was occupied by Entente forces, with the junta reestablishing control over the island. The island participated in an uprising in 1932 in line with the Rose Rebellion in mainland Auratia. In 1933, San Miguel was liberated by a combined Hallandic-Estmerish naval force, and independence was awarded in 1936.

San Miguel began a transition to a more socialist economy throughout the 1940's and 1950's under the long period of rule by the National Labour Party (PNT), which governed the island for three decades. During this period, San Miguel transitioned to a more controlled economy, introducing socialist elements into how the economy was managed as well as corporate structures, such as mandating the establishment of collectives for a majority of businesses and corporations. It also heavily invested in greater workers rights such as mandatory union membership, as well as investment into education and healthcare. The PNT became increasingly authoritarian, and throughout the 1970's, the country experienced a period of civil instability, further exacerbated by significant natural disasters in 1980 and 1984. This period came to an end in 1983 when some economic reforms were enacted, including lifting restrictions on capital flows, which contributed to a banking and economic crisis in the late 1990's and early 2000's. Since the recession of 2005, the country has steadily recovered economically but has continued to struggle with aspects of wealth inequality and rising crime.

San Miguel is an active participant in international affairs, becoming a member of, or observer to, numerous regional organisations and initiatives. It is a member of the Community of Nations, and has actively participated in peacekeeping missions across Coius since 1963. In addition, it is a member of other organisations such as the International Council for Democracy.

Etymology

San Miguel is the Auratian name for Saint Michael, the patron saint of the military, and the patron saint of Werania and the Weranic kingdoms in existence at the time of it's discovery. It was named and partially mapped by Weranian explorer Johannes Hossinger, with the name Gaullicised after the first Euclean settlement was established on the island. The island received its name of San Miguel, when it became part of the Kingdom of Auratia.

The native name for the island was aberkantaferka meaning "black island", a reference to the volcanic rocks and soil found on San Miguel.

History

Precolonial History

Prior to Euclean colonisation, San Miguel was inhabited by an indigenous people known as the Guanifrios, meaning "cave dwellers", which was an interpretation of a cave used as a tomb as a place of habitation. Genetic studies from recovered mummified bodies, as well as from the modern criollo population have found similarities between the Guanifrios and the Berber peoples of neighbouring x and the Coian mainland, which has also been reflected in the similarities between the Berber and Guanifrio languages.

Radio-carbon dating of different archaeological sites around the island have put the first human inhabitants arriving on the island at around 1000 BCE, although debate exists as to how the first inhabitants arrived there, as well as whether or not the Bebers on the Coian mainland had any knowledge of seafaring or navigation techniques prior to the Irfanic conversions and interactions with both Rahelic and Pasdani civilisations to the west and southwest.

According to some Irfanic texts, the Guanifrios were arranged into five broad tribes inhabiting various parts of San Miguel; the Maxos in the south and southeast, the Cañeche in the south-central and west part of the island, the Bimbaches in the northwest, the Auaritas in the north, and the Gomeros in the east. These were not tribes as such according to these texts, but rather loose familial associations with different regions of the island. These regions were governed by a series of local rulers or guanarteme, with some overall power over the island vested in the position of a king, or mencey. Studies of Irfanic texts have stated that the Guanifrios often relied on local leaders more often than any central power, and that only when threatened was a mencey ever crowned, although increasingly after the Irfanic conversions of the Guanifrios did the role of menceyros become more important and powerful.

Guanifrios practiced a polytheistic religion known as igeñitagelda, meaning "sky realm". Igeñitagelda was considered to be a somewhat complex religion with its own dedicated gods and goddesses, its own hierarchy, as well as priests and priestesses fulfilling different and specialised roles. In addition to multiple deities, Guanifrios believed in the ameqhuancal, or the Great Spirit, believed to be a universal life force beyond the realm of both deities and humans. Both prayers and incantations formed parts of Guanifrio religious practices, with worship practiced in temples and in open air, especially at sacred sites on significant occasions. Belief in an afterlife was present in igeñitagelda, although the Guanifrios believed it to be a progression rather than any reward or punishment. Mummification was practiced, with the dead kept inside sacred caves in the Sierra del Fuego. During the harvest festival of Beñesmen, the Guanifrios would go to their sacred caves and share food with their dead, as a means of helping them in the afterlife.

Most Guanifrios lived in small villages with few larger settlements, many of which were located along the coast acting as trading ports, particularly in the west of the island. Houses were of stone construction and circular in shape, with thatched roofs and semi-circular outer walls forming a small yard out the front of the house. Houses would also have another low circular stone pen located adjacently which is where livestock and poultry were kept. Roofs were steep and ended to a point. Livestock and poultry provided the Guanifrios with their primary source of food and clothing, with bones used for religious rituals and for implements for writing and sewing.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Guanifrios were engaging in trade with the Solarian Empire, the former trading animal skins, wine, and obsidian and the latter trading grains, wine, and metals. Solarian records state that the empire received shipments of obsidian from an area referred to as Terra Orientalis, which were highly prized by merchants and traders.

Irfanic Conversion

Irfan was introduced to San Miguel through both converted Berbers and Rahelic traders from the Coian mainland and the island of x, with San Miguel being one of the last islands in northern Coius that Irfan reached. It is estimated that it arrived on San Miguel no earlier than 980 CE, with many historians putting the date between 1000 CE and 1020 CE, the latter date being the latest possible introduction date and coinciding with the first attempts at mass conversion. As with other places in Rahelia, the conversions were forced, and this inevitably resulted in the upheaval of the social order of the Guanifrios, many of which abandoned coastal settlements and fled inland. The attempted conversions also resulted in the abandonment of the rule of the guanarteme and the centralisation of power to the mencey, ultimately creating an unrecognised but widely acknowledged kingdom on the island.

In 1020 CE, the first major expedition to the island was launched by Rahelic commander Aamir bin Nusayr Al-Kharashi against the Maxos in what is modern-day Agalán. Al-Kharashi demanded to meet the local chief upon his arrival at the village, whereby Al-Kharashi claimed the land in the name of the x, and when the village chief refused, Al-Kharashi ordered the villagers to be slain and the village raised. Word of the massacre reached neighbouring tribes, who came together and elected Guanacaro as mencey. Guanacaro rallied the tribes and clans of the Guanifrios and assumed supreme command of the island and its inhabitants. He ambushed Al-Karashi's forces near the village of Chantoche and won the first victory against the Irfanic forces, forcing them back to the razed Maxos village. Another pitched battle saw a minor victory by the Guanifrios under Guanacaro, which forced Al-Kharashi to retreat across the x Sea.

Another invasion force arrived in 1032 under the command of Zubair ibn Sayyar, this time landing in the southeast of San Miguel in the domain of the Cañeche, who immediately rose up to resist the invaders. Lead by their chief, Cahuaro, the Cañeche resisted but were pushed out of their lands and forced to retreat to the mountains. Ibn Sayyar pursued them, and defeated Cahuaro in the Battle of Taoro, in which Cahuaro was killed and the remaining men and boys slayed. The women and girls were sold into slavery. Guanacaro, who was still mencey over the rest of the island, marched south and again won a victory, forcing ibn Sayyar to retreat to the sea, before defeating him again on the modern day Playa Negra in the north of Laguira.

Despite the failed attempts at conquest, Irfan began to spread among the Guanifrios, who began to convert to Irfan in increasing numbers. By 1100, only a few holdouts in the Sierra del Fuego adhered to the old religion. However, Guanifrio Irfanic practices were esoteric in that they blended elements of igeñitagelda with Irfanic beliefs and practices. These included the use of animal sacrifices on sacred holidays and festivals, and the use of open air worship at older sacred places. One of the aspects of Guanifrio Irfan was the lack of mosques, as building techniques were not advanced enough to construct large buildings, and as a result, worship became more personalised to individual families, although communal worship was encouraged where possible.

The widespread adoption of Irfan in San Miguel changed additional aspects of Guanifrio society, with many of the older names Rahelicised, or adopting Berber names from the mainland. The former priest classes and their names changed in accordance with Irfanic customs, while local legends of devils and other spirits were modified as well. The guanartemeros that conducted local administration became important leaders for religious ceremonies, and the mencey adopted the role of the most senior religious authority in San Miguel.

Early Colonisation

Weranian explorer Johannes Hossinger was the first Euclean since the Solarian Empire to reach San Miguel, doing so on June 19, 1415. Hossinger sailed south through the x Sea between San Miguel and x, mapping the west coast, before sailing south along the eastern coast of Rahelia and the northern coast of Bahia. On his return journey, Hossinger sailed up the eastern coast of San Miguel, mapping that area of the country and giving it its first official name; Sankt Michael, after the patron saint of the military.

Eucleans would return to San Miguel the following year, this time under the command of Poveglian explorer Vincenzo Garzoni, who landed ashore near Tajao on May 27, 1416, marking the first official landing of Eucleans on the shores of San Miguel since Solarian traders first stepped ashore several centuries earlier. Garzoni interacted with the locals and received supplies in the form of dried meat and fresh water, before returning to Poveglia. Another landing that September, made under the flag of the Verliquoian Empire by Clement Vérany, was also made, although a misinterpretation through translators resulted in a scuffle that saw two locals killed. The island's position and favourable currents and winds attracted attention from many of the Euclean maritime powers.

Settlement of the islands would not begin for several years until the establishment of a settlement near modern day Tajao in the north of the country by Gaullican Heliot Serre on January 16, 1422. The settlement was intended to be a trade port, and was named Port Maguerite after the monarch at the time. Although the port facilitated local trade, it quickly became a centre for regional trade with eastern Rahelia, and as a result, trade and the population grew rapidly. Many Guanifrios migrated to the area around Port Maguerite, causing tensions between the Verliquoian colonists and the Guanifrios, which attracted the attention of mencey Asmed Parsa, who travelled to Port Maguerite in 1430 after a particularly violent confrontation. Unfamiliar with Euclean colonial practices and property customs, Parsa attempted to remove the Verloquoians from the trade port by force. Parsa's forces were defeated in the First Battle of Port Maguerite, with the settlement holding out until the arrival of reinforcements from Euclea. The Verliquoians regarded the attack against Port Maguerite as a carte blanche for a more widespread invasion of San Miguel, with another force arriving in October 1430 to defeat Asmed Parsa and place the Guanifrios under the rule of the Empire. Led by Robert Deloffre, Duke of Sancerre, the force numbered some 1,500 soldiers from Euclea in addition to 250 locals from Port Maguerite. The force marched south along the western coast, seizing numerous towns before confronting Parsa's main force outside Agalán, where Parsa's army was defeated, Parsa himself killed in battle. As no tribe or clan was willing to nominate a replacement, the Guanifrios came under the rule of the Gaullican Empire.

With the conquest of San Miguel, the island was renamed to Saint Michel from the Weranian name on maps, and given the status of colonie royale, and was placed under the auspices of Clement Vérany, who began establishing settlements in the south. Vérany introduced the concept of travail levé, a form of tributary labour in which men, women, and children were conscripted into work gangs that were used on public projects, which was similar to the corvée used in Euclea, the difference being that the Guanifrios were able to be raised by the local government only, and not the private landowners establishing themselves on the island. The social upheval severely impacted the harvesting of grains on the island, and resulted in the first recorded famine on San Miguel taking hold in 1432, which lasted for two years and severely impacted the growth of the Gaullican colonial settlements on the island, particularly Port Maguerite. The administrative capital was moved south from Port Maguerite but was temporarily relocated when the El Nublado volcano erupted in 1430, which casued the aforementioned famine, and resulted in significant volcanic activity in southern San Miguel, culminating in the El Altar Massif eruption in 1439, itself triggering another famine across the island due to widespread crop failure. Volcanic activity continued until 1444. The Gaullicans, believing the eruptions and famines to have religious significance, abandoned Port Maguerite in 1443.

Eucleans had returned to San Miguel by 1470 with the Gaullicans establishing another trade port, this time establishing small trade ports and concessions in areas which had been singificantly affected by the El Nublado and El Altar eruptions. The Gaullicans established settlements in the north and south of the country at Tajao and Agalán respectively, with the First Hennish Republic establishing two ports, one in Laguira and one near La Aguerra. The Gaullicans eventually reinhabited Port Maguerite, but most trade passed through Tajao. As the island's inhabitants did not have much in the way to resist them, they accepted the Euclean's presence and began moving into these settlements. Over time, these settlements became important stopping points for Euclean explorers sailing to the Asterias, as well as along the eastern coast of Coius, particularly Bahia.

One of the most destructive disasters to occur on San Miguel occurred between November 17 and 18, 1522 when a large earthquake produced mudslides and landslides after heavy rains had occurred. The earthquake, centred northwest of the reestablished capital, Laguira, caused massive damage across the southern corner of San Miguel, with landslides affecting all settlements in the vicinity of the El Altar Massif and surrounding ranges. The result was a death toll of 8,000 people overall and widespread destruction of Agalán and Laguira. The earthquake and the subsequent rebuilding efforts on the island resulted in the spreading of the plague in squalid conditions that the survivors were forced to live in, creating an epidemic that did not end until 1530, and resulted in a further 7,000 deaths, as well as a widespread depopulation of many settlements in southern San Miguel. This event weakened the Gaullican and Hennish presences on the island, as some of the largest settlements were severely damaged by the earthquake. This left essentially the ports at Tajao and La Aguerra the only functioning ones on the island, while the rest rebuilt.

The first Auratian settlements appeared on the island in the early 1500's, and were principally centred in the north and west of the island, these being the future cities of San Agustín and San José, which suffered minor damage in the earthquake that damaged Agalán and Laguira. Unlike the Gaullican and Hennish settlements, these were purely commercial establishments administered by the Gremio Mercantil de San Miguel (GMSM), an association of merchants who saw potential in establishing trade links between the Asterias, northeastern Rahelia, Bahia, and Euclea. After the disaster of 1522, the GMSM agreed to purchase Agalán and Laguira off the Gaullican and Hennish governments, assuming ownership of almost the entire island.

Kingdom of Auratia

The Gilded Wars saw San Miguel targeted by the Royal Gaullican Navy. San Miguel was well prepared, with substantial fortifications protecting the ports of Agalán, Laguira, and Tajao, with additional fortifications established in Lodero, San Agustín, and San José. Approximately 5,000 professional soldiers were stationed on the island under the command of José María de Lossada, with a supplementary force of militia units numbering an additional 3,200 militiamen. The Royal Gaullican Navy began their assault on San Miguel on December 22, 1714, commencing a bombardment on Fort Barceló at Cabo Blanco, just north of the port of Tajao. The soldiers of the fort, commanded by Ignacio Córdova, fought valiantly, sinking three of the fifteen Gaullican ships that had pounded the fort into submission. The Gaullicans then sailed south down the eastern coast of San Miguel, forcing de Lossada to redeploy his principal force to the east to prevent a Gaullican landing. By the time he had arrived on December 29, the Gaullicans had already landed. He engaged them the following day near the town of Arure, and while he had prevented the Gaullican capture of the town, de Lossada was forced to retreat as Gaullican soldiers had marched around him through the southern heights of the Sierra del Fuego. De Lossada fought a series of rear guard actions but ultimately was forced to retreat to Laguira, while the navy had engaged Auratian defences at the Battle of Timagada Bay on January 3, 1715. A surprise victory at the Battle of Gamarra on January 6 handed the initiative to de Lossada, who followed it up with a crucial victory over the Gaullicans at the Parachure action the following day, when Gaullican naval ships providing fire support mistook retreating Gaullican soldiers as Auratians and fired two salvos, killing dozens. A final battle near La Aguerra forced the Gaullicans off the island. However, the Royal Gaullican Navy continued to harass the island and cause problems for shipping in the region, engaging in raids against important ports, particularly Tajao, which was raided five times, and Agalán, which was raided seven times. Laguira was raided twice more through the conflict.

Auratian Republic

Juan Antonio Urráburu Arechabala

La Lucha

San Miguel's isolation and early settlement that by the mid-19th century, the island had developed a unique cultural blend of Euclean, Rahelic, and Bahian influences, with centuries of Euclean habitation and influence on the island. The criollo and native-born Euclean population known as criollos blancos or "white creoles" had begun seeing themselves not as Auratian but as a separate people group. This national identity became part of a wave of artistic expression, particularly in literature. Poet Simón García Morterero wrote Mi país, que bella, which became influential in cementing the San Miguelan identity apart from the Auratian. Prominent writer and politician Domenico Siurana Bescós wrote the essay Sobre el tema de la independencia, or "On the Subject of Independence" in which he outlined the argument in favour of independence from Auratia, by force if necessary. The essay became part of the founding manifesto of the National Movement for the Total Independence of San Miguel (MINTSAM), founded by pro-independence activist and writer José María Malasaña Azopardo, which was established on January 16, 1869. The organisation represented the first serious challenge to Auratian authority.

Criollo nationalism was heavily focused on rediscovering the indigenous heritage of the island, and a number of criollo nationalists rejected the writings and essays of white writers. Criollo writers such as Aarón Molla Arán criticised the criollos blancos for becoming historical revisionists and excluding the horrors of the economienda forced labour systems, in addition to promoting an inaccurate and idealistic view of San Miguelan history. The divisions lead to the MINTSAM splitting in Feburary 1871 with the criollo members forming a separate movement, the Authentic Movement for Independence (MAI) on February 26, 1871. MAI were considered more radical than MINTSAM in their demands for independence and were willing to resort to violence if necessary in order to achieve their aims, while MINTSAM wanted to pursue independence through legislative changes. The MAI was lead by Miguel Aréizaga Gravina, a university student who had supported calls for independence and lead a faction of the MAI known as Los Jovenes, a group of radical university students and professors who began to make public calls for independence. Aréizaga

With San Miguel connected to Euclea through undersea cables routed through Geatland, Cienflores was more connected to Laguira and could receive news much more quickly, and news of the independence movement reached the Auratian government, who took swift action to order the governor, Carlos Lapeña Longa, to act in order to prevent a seccessionist movement from developing. Lapeña responded by banning both the MAI and the MINTSAM, arresting its leaders and charging them with sedition. In what became known as the Juicios Grandes, the leaders and members of the respective independence groups were tried and sentenced to 40 years imprisonment for sedition. The trials created civil unrest in Laguira, which was suppressed by local police and the Auratian Army. Lapeña requested extra military support from Cienflores in order to maintain law and order on the island.

In 1881, Governor Juan Martín Mazarredo Larrea released a number of pro-independence activists on compassionate grounds, believing that the organisations they had run were long since disbanded and the individuals of no real threat. Among those released was Bartolomeo Azcárraga Salvado and Domenico Céspedes Sánchez who formed the National Movement for Total Independence (MINT) on December 3, 1881 at a gathering at the Riego Hotel in Laguira. MINT was intended on bridging the gap between white criollos and mestizo criollos and included former members of MINTSAM and MAI who had not been arrested or who had fled and had returned to San Miguel under amnesty. The movement would remain underground, relying on grassroots support for its cause, as economic growth and propserity had largely influenced the population against independence, particularly with the flow of investment capital from Auratia into the island's businesses. During this time, the independence movement supported local reformists and other candidates, including a number of anti-clerical

Democratisation

Declaration of Independence

San Miguel was substantially affected by the Great Collapse, seeing a rise in unemployment and a decrease in exports for the first time since the 1860's. One of the wealthiest states in Auratia, San Miguel's economic performance reflected that of its Euclean counterparts. The National Liberal Party lead by Manuel Cañas González, in power since 1907, had instituted a number of economic reforms that improved the ability for banks and businesses to do business more freely on the island. The PLN was disparaging of the national government's debt policies which caused significant problems on the island, as most of its trade was conducted with foreign nations. Hyperinflation began to increase, and this vritually halved San Miguel's trade within several months. In addition, the hyperinflation caused a banking run in San Miguel, causing the collapse of the branches of Auratian banks as well as local San Miguelan banks, including the Mercantile Investment Bank (BMI) and the San Miguel Agricultural Bank (BASM). Unable to fix the issues and finding the government in Cienflores uncoopertative, Cañas resigned on January 1, 1914 and called fresh elections. The elections were won by the Labour Party candidate José María Urrutia Morillo, who was sworn in as Governor in August that year.

Urrutia began to implement the same social welfare policies that the central government in Auratia had done, and had a good working relationship with the central party hierarchy, particularly Premier Jacobo Molinero. Urrutia also used the crisis to advance his advocacy of state ownership of important companies and used the unemployed for substantial infrastructure projects. In December 1913, the State Congress of San Miguel passed the Ownership of Strategic Assets Act (LPEA) which enabled Urrutia and the state government to begin the acquisition of numerous businesses affected by the economic crisis. The first was what remained of the BMI and BASM banks which were consolidated into the Bank of San Miguel, with the railway transferred to state ownership soon after, the state creating the Railways of San Miguel (FSM). By 1915, twelve different state owned companies had been created. Urrutia had also petitioned for the government to send increased financial aid to San Miguel, and this was used in essential infrastructure projects, among which was a second road crossing the Sierra del Fuego and the completion of the East Coast Railway between Tajao in the north and Laguira in the south via the cities of Gueleleita and Lodero in the east. Gradually the San Miguelan economy regained momentum, and with it, the popularity of Urrutia. Labour would come to dominate San Miguel, winning the 1918 and 1922 elections. The 1918 elections were notable in that a new party was elected to the State Congress that broke the two-party domination of the legislature.

Former Labour Party politician and pro-independence activist Juan Martín Aguinaldo Cadaval had been able to break the two-party system in San Miguel by 1922, by becoming the first MINT leader to be elected to Congress. Throughout the first two decades, the MINT had grown in size, and formed a bloc with the Labour Party in preparations for the 1922 state elections. Aguinaldo and Urrutia had a good working relationship, which benefitted the MNIT as it escaped the otherwise inevitable end at the hands of the Auratian Army and police.

On November 24, 1926, the city of San Augustín was struck by a magnitude 5.3 earthquake that was centred sixteen kilometres to the east of the city, resulting in the destruction of over 4,000 houses and buildings. 91 people were killed and over 400 were injured. The substantial amount of damage inflicted upon the city of San Augustín was substantial, and had a singificant economic impact on San Miguel. Aid to the island was slow in coming, with political turmoil on the continent preventing many states from providing aid. Of the nations that did, Halland was the largest and the one most invested, sending ships with food and blankets to San Miguel. Auratia didn't send aid until January 1927.

The events of September 20, 1927 had a profound impact on San Miguel. The island, which had maintained the Labour Party in power, this time under Alfonso Lladó Quesada. Lladó was put forwards as a moderate candidate with sympathies to the independence movement as part of the 1926 elections, which had given the Labour Party a confident majority in the State Congress. The lack of support from the central government and the functionalist takeover of Auratia prompted the MNIT and Aguinaldo to act. On September 22, 1927, Aguinaldo and elements of the Popular Independence Force (FPI), alongside rebel units including both regiments of the tabores, marched into the capital Laguira, and demanded the resignation of Governor Lladó, who accepted it without hesitation as this was previously discussed in the leadup to the events in Auratia. Lladó gave a resignation speech on national, and informed the government in Cienflores of his decision through a telegram. Aguinaldo was hastily sworn in as President of the Transitional Government, and pronounced San Miguel as an independent nation that evening.

Occupation

The government of Auratia rejected the declaration of independence, and preparations were made to retake the island. San Miguel was considered to be an important strategic asset, and this was recognised by both the Grand Alliance and the Entente. The progress Gaullican and Entente forces had made in Euclea had caused concern among the fledgling independent government in San Miguel, and hope for protrection from the Grand Alliance was diminishing. On October 3, Aguinaldo prepared a list of important government officials to be taken overseas in the event of an Auratian or Gaullican invasion. Aguinaldo had also contacted the Hallandic government about seeking protection in the event of an invasion, as all potentially friendly governments in Euclea had been invaded or were actively fighting the Gaullicans.

As plans to evacuate important pro-independence officials from the government were being made, the island's defences were being prepared. Auratian loyalists were rounded up and placed inside prisons, particularly the military prison at Muñique in the centre-west of the country. In addition, weapons caches were placed in the Sierra del Fuego for a resistance movement to continue beyond the invasion. In addition, defences were being prepared, with likely landing grounds identified and military units deployed in preparation.

Plans for an invasion were begun almost immediately after the declaration was received by the government, but these were not seriously considered by the Gaullicans until late 1928, when the strategic situation regarding supplies between Euclea and Euclean colonies and Entente allies in the Asterias was fully recognised. The Auratian high command had already formulated a plan regarding a series of beach invasions in the north and west of San Miguel, as the eastern coast had no conducive geography for a seaborne invasion. Dubbed Operation Claudia, the invasion called for 3,200 Auratian marines and an additional 1,500 Gaullican marines to land in the north and west of the island.

The invasion began on March 13, 1929

In 1933, a combined Estmerish-Hallandic fleet attacked Laguira, including the vessels stationed there, in what became known as the Battle of Timagada Bay. During the battle, Laguira and its surrounds sustained significant damage, and several hundred civilians were killed. However, the lack of substantial Entente naval forces in the area meant that the island quickly came under the influence of Allied naval forces, and an attempt to reassert control failed in what became known as the Battle of Cabo Blanco. Soon after, Hallandic forces landed on the island to establish control, and took the surrender of the local military and naval garrison.

Independence

In January 1934, Juan Martín Aguinaldo Cadaval returned to San Miguel aboard a Hallandic Navy destroyer from exile in x, and established an interim government in Laguira at the behest of occupation authorities. This angered the civilian administration in Auratia, which demanded that officials from Cienfuegos be permitted to travel to San Miguel. Because Aguinaldo and other independence leaders had rebelled against the September Clan, the government of Héctor Alvear had considered the actions of it to be illegitimate, and thus a pro-independence government was seen as undermining Auratian authority in San Miguel. Halland invited both Auratian and San Miguelan officials to a conference in Avelon to discuss the matter of San Miguelan sovereignty, but both sides refused.

Aguinaldo established the San Miguelan Transitional Authority on February 1, 1934, and set about establishing government agencies and ministeries utilising members of the former cabinet of state secretaries that existed in the government of Alfonso Lladó Quesada, Lladó himself appointed as Vice President and acted as a senior adviser. Most of the cabinet positions that existed prior to the outbreak of the Great War were transferred to new ministries, with new ministries such as that for Foreign Affairs and War created from scratch. As there was no elected legislature, Aguinaldo ruled by decree, and established many of the institutions through this method. In 1935, he alongside other government officials, travelled to Morwall in Estmere to participate in reparation negotiations with Gaullica, the government seeking reparations for the damage and hardship caused during the occupation between 1929 and 1933. However, as San Miguel was not recognised as an independent state, and whose sovereignty was disputed, Auratian officials blocked any attempts for San Miguel to join the negotiations in a formal manner, forcing Aguinaldo to return to San Miguel without any reparation payments.

A second attempt to bring the leaders of Auratia and San Miguel together was accepted, and Aguinaldo travelled to Avelon to meet with Alvear on June 27, 1934. Both parties were given room to outline their case, with Auratia claiming that the actions of the September Clan were retroactively rendered illegal. Aguinaldo stated that San Miguel had declared independence before the Great War, had been liberated by foreign powers, and that no Auratian officials were present on the island. The negotiations were somewhat successful, and both Aguinaldo and Alvear signed the Avelon Memorandum, an agreement to enter into negotiations for San Miguelan sovereignty.

Further negotiations were conducted in Carutagua in Nuxica, considered a common neutral ground between the two countries, with officials from both countries attending a series of meetings there between October 1934 and January 1935 to establish the framework of San Miguelan independence, with agreements ranging from travel arrangements to trade and the transfer of former government assets and personnel. In addition, Auratia and San Miguel would both establish a formal bilateral relationship as soon as possible. The Carutagua Agreement was signed on January 29, 1935, with San Miguel set to become an independent state the following October.

On October 1, 1936, the conditions in the Carutagua Agreement came into effect, and President Aguinaldo officially proclaimed San Miguelan independence on radio, which was broadcast throughout San Miguel. Shortly afterwards, Aguinaldo set about officially establishing his cabinet as well as government institutions. In addition, he called a constitutional convention which would draft a constitution to establish basic legal rights and privileges within the country, with the goal of having these institutions and constitution in place by scheduled general elections in 1939.

In addition to domestic policy, Aguinaldo also began to establish San Miguel's foreign policy and relationships, completing a tour of victorious Grand Alliance powers in Euclea between May and July 1937, and issuing reparation claims with the Community of Nations in December 1936, and becoming a full member of the organisation the following year. Aguinaldo also sought and was granted significant loans from Halland and Nuxica in order to fund and sustain the first years of San Miguelan independence.

Democratic Rule

The general election of 1939 provided an opportunity for the left-wing parties in San Miguel, which had united under the People's Radical Movement (CRP) and were lead by Vincente Arcur Galán. Arcur, the leader of the National Labour Party (PNT), provided a much needed boost to the CRP's popularity and public image, especially among the working classes of San Miguel. Arcur campaigned on a platform of a bright and prosperous future for all, to abolish the old Euclean systems of wealth concentration, as well as providing greater benefits for working class San Miguelans.

Opposing the CRP was a coalition of parties lead by the interim president Juan Martín Aguinaldo Cadaval, who had reformed the MINT into the National Movement for Social Progress (MNPS), a party which was moderate in terms of overall political standings but received heavy support from both the Catholic Church and business interests. The MNPS itself was a collection of centre-right and right wing politicians, dominated by the centre right. They had the support of local businesses, and also promoted themselves as the party to rid San Miguel of colonial influences, including the large number of Auratian companies who owned infrastructure.

One of the first elections monitored by the Community of Nations, the 1939 general elections were the first since San Miguel declared independence in 1927. The campaign was marred by accusations of vote rigging and small-scale political violence, predominantly in poor urban communities as rival factions fought one another. In addition, the election was also noted for the significant influence of the Catholic Church, who encouraged its members to vote in fabour of the MNPS. This campaign was effective in rural areas of the country, and helped the MNPS achieve it's first electoral victory.

The victory of the MNPS saw Aguinaldo become president and the CRP coalition collapse due to escalating infighting between factions. The proliferation of weapons stockpiled during the emergency period and the occupation had created significant problems for the new government in curbing political violence now emerging in many of San Miguel's cities. As San Miguel essentially lacked a military to impose law and order in the country, in October 1939 the National Congress passed legislation to extend the state of emergency in existence since the outbreak of the Great War. The legislation created the Fuerza Pública or Public Force, which was an organised paramilitary that would engage in public law and order operations while the military was formed. Violence subsided by May 1940, however the state of emergency remained in place.

Aguinaldo began implementing his campaign policies in June 1940, with the passage of the Nationalisation and Consolidation Law. This law allowed the government to nationalise and consolidate essential businesses that operated on the island. Most of San Miguel's essential services, including electricity generation, telecommunications and railways, were still owned by Auratian state enterprises, and the transferral of all assets in San Miguel to the San Miguelan government was essential. Almost overnight a raft of new companies were created to manage San Miguel's essential services. These included Electricidad de San Miguel (ESM), which generated and provided electricity to San Miguel, the Compañía Ferroviaria de San Miguel (CFSM), which operated the railways, and the Servicios Nacionales de Teléfonos y Telegramas (SNTT) which operated San Miguel's telegram and nascent telephone services. In addition to being independent of Auratian control, they also provided the San Miguelan government with much needed revenue. The nationalisation also placed San Miguel in an important position as it had an important relay between Euclea and various colonies in Bahia for telegram services. The nationalisation prompted a series of heated messages delivered between government officials, as Euclean governments were wary of a new government controlling. Aguinaldo managed to control the situation, and an agreement was reached.

In 1941 Aguinaldo launched a series of additional economic reforms, introducing a series of protections for San Miguelan agriculture to prevent cheaper imports from both the labour used in Bahian colonies as well as imports from the temperate parts of northern Rahelia. This was intended both to aid in the development of San Miguelan agriculture as well as improve export opportunities, in particular to Euclea. A series of negotiations took place but went nowhere, and Aguinaldo was forced to seek exports elsewhere, save for Auratia who had recognised San Miguelan independence in 1938. These reforms also expanded workers rights and saw the implementation of higher wages; by the end of the decade, agricultural wages were the highest in all of Coius, and were higher than in some countries in the Asterias and Euclea. Paid holidays were expanded to a full month, paid sick leave was doubled from five days to ten, and six weeks of paid leave for mothers before and after childbirth was introduced.

These policies helped set the basis upon which the PNT would build upon to introduce aspects of socialism into the economy without overtly declaring San Miguel to be socialist. These also helped drive the economic development and industrialisation of San Miguel, with improved mechanisation of farming, a growing middle class, and increases in production and consumption of consumer goods.

El Dominio

With the victory of the PNT in 1943, the period referred to as El Dominio, or "The Dominance", a term coined by historian Omar Qamari Saldaña in 1991, Vincente Arcur Galán began to orientate San Miguel to adopt a more leftist stance with regards to economics and foreign policy, while maintaining positive relations with existing allies, particularly Halland. Arcur began to institute a number of social and economic reforms not long after he was sworn in as president, building more schools, making education free and mandatory from the age of six, as well as creating the Public Health Service that extended healthcare coverage to all San Miguelans. Companies with more than one non-familial employee were required to give proportionate dividends to their employees, and large companies were mandated to allow the workers to elect representatives to governing boards, with one representative per 50 employees. These changes helped align San Miguel with many of the communist and socialist economies in the world. Arcur began a tour of socialist countries, establishing new bilateral relations, especially with those of common Auratian heritage. While Arcur wanted to expand San Miguel's bilateral relations, he also recognised the need to maintain good relations with non-socialist countries, especially with San Miguel's strategic position, and so sought to reassure San Miguel's non-socialist allies. Despite this, Arcur extended his support for independence movements in Bahia and wider Coius during a speech to the Congress in September 1944. While San Miguel did not actively fund these movements, it did become a conduit for both revolutionaries and material supporting independence movements flowing into Bahia.

Throughout the 1940's, the Arcur administration continued to develop and industrialise using significant investment from both communist and non-communist states. These included a substantial expansion of Laguira's international airport, which became an important stopover for airlines operating between the Asterias and Euclea. Arcur also expanded railways and the ports of Agalán, Laguira, and Tajao which became among the largest in northeastern Coius, with San Miguel becoming one of the wealthiest countries on the continent. In 1944, Congress passed the Expansion of Rights And Privileges of Workers Law, which transformed state owned enterprises into autonomous worker's cooperatives. The passing of the law had unintentional economic and financial consequences for San Miguel at a time of global economic depression and significant financial pressure. Although the country did not have as much trade with Euclea as it had with Asteria Superior, particularly Halland and Nuxica, Auratia remained a key market for San Miguelan exports. With the invasion of Auratia by Etruria in December 1943 that sparked the international intervention, demand for San Miguelan exports virtually ceased overnight. This put pressure on San Miguelan businesses, which in turn reduced tax income for the government, making it more difficult to pay the loans given to it by Halland and Nuxica in the previous decade. The passing of the LADPT in 1944 exacerbated the problem further by depriving the government of direct income from the now former state owned enterprises, the revenue from which was being used in part to service San Miguel's debt repayments. With a lack of funds available, the government became unable to repay the loans, with this situation becoming apparent not long after the law was passed. Arcur was opposed to the cutting of social spending, and instead travelled to Astoria and later, Carutagua, to renegotiate San Miguel's outstanding debt. These negotiations proved unsuccessful, and Arcur returned to Laguira facing a debt crisis. A series of heated exchanges via telegram were made between the foreign ministries of Halland, Nuxica, and San Miguel, in which the former agreed to a delay in payments while Arcur entered into another series of heated exchanges, this time with Finance Minister Juan Sebastián Sarmiento Espinar over proposals to significantly reduce government expenditures. Instead, Arcur opted to increase taxation, imposing an emergency increase in income tax by up to 35%. Demands for more reparation payments from Gaullica were also made, and were unsuccessful. Negotiations to restructure the national debt were successful, and Arcur returned to San Miguel.

The debt crisis precipitated a constitutional crisis in which Sarmiento implemented a wage freeze on civil servants without consultation with Arcur, instead acting on the advice of the Central Bank of San Miguel, with Arcur in Halland again entering additional negotiations surrounding debt restructuring. Sarmiento was fired through a telegram sent from Astoria, but refused, insisting that the President must be in the country in order to dismiss ministers. When Arcur returned to San Miguel after successfuly negotiating a restructure to San Miguel's national debt, he travelled to the Ministry of Finance in Laguira to confront Sarmiento, who refused to step aside. Although Arcur as president had the power to dismiss cabinet ministers, the process of which was not properly defined, and this became the source of contention between him and Arcur. Arcur then asked the Congress to vote on Sarmiento's continued presence within the Cabinet of Ministers, Congress voting to keep Sarmiento as Minister. Arcur then instructed Sarmiento to reverse the wage freezes for public servants, which Sarmiento agreed to in light of increasting protests and additional civil instability. The tax increases became permanent, and Arcur used the additional revenue to fund a wide number of social and industrial policies.

Between 1944 and 1951, the Arcur administration pursued a policy of significant investment into social policies and economic industrialisation and development. Corporate taxes were raised on companies operating in San Miguel, and these were used to fund industrial development and modernisation, including investment in port facilities, particularly in Agalán and Tajao, as well as promoting economic diversification. Manufacturing output was increased and San Miguel's manufacturing base expanded. Agriculture was modernised through improved practices and mechanisation. With the global economy beginning to recover from 1947 onwards, the San Miguelan economy also began to grow with it. This increase in prosperity lead to Arcur being Arcur being reelected in 1947. In his second term, Arcur expanded social programs, including social housing, which reduced the numbers of people living in slums from 27% in 1947 to 19% by the turn of the decade. This required significant government investment, and prompted Arcur to seek additional support and aid from socialist countries, particularly Chistovodia and Kirenia, both of which invested significant amounts of financial and material aid into San Miguel.

Arcur was succeeded in 1951 by Simón Arrabal Bahéchar, who continued Arcur's industrialisation policies and pursued a more aggressive foreign policy, providing more support for leftist groups abroad, particularly in Rahelia and Bahia. Arrabal had taken a more hostile stance to Euclean colonial policy in Coius, and continued to improve relations with the socialist bloc, particularly Chistovodia, which expanded their already significant investments in San Miguel. This alarmed many of the Euclean and Asterian states which had enjoyed cordial relations under his predecessor. Despite this, Arrabal continued to seek further investment from the socialist bloc and build greater ties with socialist nations around the world, particularly in resource-rich Bahia, securing supplies of much needed ores and crude oil.

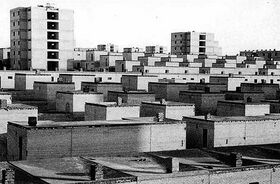

Arrabal's domestic policy was predominantly involved around continuing the industrialisation progress as well as the expansion of social housing programs, announcing in 1952 of having a goal to eliminate all slum dwellings in San Miguel by the end of the decade. To achieve this, Arrabal introduced Vivienda dirigida, or "Directed Housing", whereby vacant or appropriated land was developed into social housing, with families and couples given housing based on immediate need. This took the form of either apartments for childless couples, singles, and elderly residents, or standalone and semi-detached housing for families with children. Arrabal invited workers and state owned companies from the socialist bloc to help construct the social housing, with over 40,000 apartments and houses completed by 1955. Ownership of these residences was placed under the state through the Public Housing Service, created by Arrabal in 1952 to manage the distribution of social housing. In addition, Arrabal also instituted a number of more liberal economic policies, promoting the growth of small to medium sized businesses through the reversal of the increased tax rates imposed by Arcur, as well as reducing taxes for foreign companies establishing manufacturing and service operations in San Miguel. Outside of economic and social policy, Arrabal increased funding for the military and security services, and gave the National Police greater powers, including arbitrary arrest and detention. He also strengthened sedition laws and introduced restrictions on the freedom of the press.

Arrabal was also disliked by a number of factions within the PNT, including the social democratic factions of the party, and by the time of the party conference to select a candidate going into the 1955 general election, the divisions within the PNT threatened to tear the party apart. The social democrat faction of the party began a campaign of influence towards the moderates within the party, who then voted against approving Arrabal's candidacy for the general elections, affirming Juan Sebastián Santángel Tafalla, a moderate candidate proposed by the social democratic faction, as the candidate, who became leader of the PNT two months before the election in August 1955. Santángel won with 42% of the vote, which was less than what the PNT was expecting.

Santángel attempted to balance both the disputing factions within the PNT, as well as San Miguel's foreign policy, embarking on a tour of Euclean and Asterian nations to further strengthen existing relationships, with further emphasis on attaining support from social democratic governments in Euclea. Santángel travelled to mainly eastern Euclean countries, and also visited Auratia as part of the trip, reaffirming San Miguel's commitment to the bilateral diplomatic and trade relationship. Domestically, Santángel reduced the funding increases for the security services and rescinded the restrictions on the press. He retained many of the economic and social policies of his predecessor, and further liberalised the investment regulations in an attempt to jumpstart the economy, which had begun to stagnate after 1955.

Hardliners within the PNT had been plotting to remove Santángel from office since before the 1955 general election, and by 1957 had a plan in place for his removal. Events in June 1957 would prevent the hardliners from implementing their plans, as changes to the budget for the armed forces, including reducing salaries and perks for commissioned officers, brought about an attempted coup on June 19, 1957, in which members of the armed forces and far right groups within San Miguel attacked the Moncada Palace, seizing the palace and arresting Santángel and proclaiming a transitional government. However, crowds of supporters of the PNT and of Santángel responded by filling the streets demanding the release of Santángel. Loyalist elements of the military and police attempted to retake the palace on June 20, but were repulsed. Backed by armoured cars and tanks, the loyalists made a second attack on the palace and were successful, pushing out or killing the coup participants and rescuing Santángel. Sporadic clashes continued between loyalist and hardliner factions of the armed forces for the next two days, until the loyalists had re-established control over the country. Santángel would be returned to power, ruling from the Casa Garibay until damage at the Moncada Palace was repaired.

Beginning in September 1957, the first Women's March occurred in Laguira, with various women's organisations demanding liberalisation of San Miguel's divorce laws, as well as access to abortion. In addition, these organisations demanded increased rights for women, including the banning of marital rape, equal pay rights, and the adoption of maternal leave policies. Leaders of these organisations met Santángel to discuss the demands and proposals for law changes, which Santángel supported but were unlikely to be implemented in the remaining term, Santángel instead promising changes to the existing laws in the next term. After winning the 1959 general election by a landslide, Santángel formally approved the Código de la Familia in December 1960, which revolutionised San Miguelan social laws, among other things, legalising divorce and introducing abortion for up to 12 weeks for cases of rape, incest, fetal defects, and to save the mother's life and mental health. In addition, it also introduced six weeks of maternal leave for all new mothers, as well as a raft of other law changes.

In addition to the raft of law changes, events in northern San Miguel created economic and social problems that would affect the rest of the country going into the next decade. Beginning in September 1957, an underwater volcano at Cabo Negro in the far north of San Miguel began to erupt, severely disrupting local communities in the Cabo Negro and neighbouring municipalities. Seismic activity began on September 16, 1957, with over 200 seismic tremors associated with the initial eruptive activity. Many of these earthquakes registered V on the Mercalli scale. From September 27, black ash and water vapour began to be seen and emitted from the ocean, followed by large clumps of clay which began damaging the lighthouse at Cabo Negro, eventually spreading to 2.4 kilometres around the volcano, damaging houses in nearby villages. By the end of October, pyroclastic explosions, lava flows, and constant ashfall around Cabo Negro forced the evacuation of more than 2,000 people from three villages at Playa Negra, Tirajana, and Utiaca. By the end of the volcanic activity in 1958, some 300 houses had been destroyed, in addition to 150 other buildings. Many of those forced out of their homes were resettled in Tajao in social housing. Economic costs were significant, and contributed to a decline in economic growth by 1963.

El Reto

Años Perdidos

Modern History

Geography

San Miguel is approximately 26,593 square kilometres (10,268 square miles) in size, and is the third largest island in eastern Coius. The island is commonly referred to as la roca negra, or the black rock, owing to the colour of the volcanic rock found all over the island. It is known for its rugged terrain, active volcanoes, and very fertile soil. These features have not only protected the inhabitants of the island, but have also allowed it to flourish.

The Sierra del Fuego is the primary geographic feature of the island, and is a string of active, dormant, and extinct volcanoes that run up the centre of the island. San Miguel lies on a weak zone within the crust that results in volcanic and seismic activity taking place, with the island first forming over half a million years ago, and is considered to be among the youngest of the islands in Coius, with the volcanoes once forming a small archipelago. However, a series of long eruptions and constant eruptive activity has produced the island of San Miguel, with periodical eruptions still continuing. The island's shape has been influenced by these eruptions and volcanic activity, with the Sierra del Fuego forming an inverted Z-shape through the centre of the island. El Nublado is the tallest of the many volcanic peaks on the island, at 3,718 metres (12,198 feet) in height.

In addition to volcanoes, the island is known for its geothermal activity, with numerous hot springs found across the island. Among the most well known are the thermal baths and mineral springs of the Baños del Rey near the town of La Aguerra, which have alleged theraputic properties. The geothermal activity also provides San Miguel with a significant proportion of its renewable energy.

Much of the country is covered in rugged, hilly or mountainous terrain with few flat areas, among them a broad coastal plain in the south of the country known as the Abanico de Lava, as much of the area is composed of older lava flows from the volcanoes to the north. The soils in this region are as fertile as elsewhere on the island, however it is mostly urbanised with the nation's capital, Laguira, and many smaller towns located in this region.

The northern half of the island is known for much the same terrain as elsewhere, however the land does not slope down gently towards the sea, but instead ends abruptly in an area known as the Acantilados Negros, or Black Cliffs, region. Here, many caves, sheltered beaches, and outcrops can be found. In addition the rocky shores and the cliffs are home to both colonies of seals, sea lions, and seabirds. These also provide natural pools of sea water which are popular with locals, and are collectively known as the Baños del Mar.

Seismic activity occurs frequently on or around the island and is principally associated with the volcanic activity and the geological history of the island. Despite being located far from the Vehemens Rift, San Miguel's vulcanism and seismic activity is associated with that rifting as the West Vehemens Plate is moved westwards, while the hotspot underneath the island remains. Such activity is thought to have occurred for millions of years, and is responsible for the much larger island of x to the west. Because of the relatively new volcanic activity that created San Miguel, much of the seismic activity is associated with the movement of magma, or the movement of volcanic rock across oceanic crust, in what is known as a décollement, where the slumping of large areas of volcanic rock deposits creates earthquakes in a similar manner to certain types of fault line. These also create cracks and rifts on land which also result in earthquakes. Most of the earthquakes that occur in San Miguel tend to be small and largely unnoticed, although a number are felt by people every year. Damaging earthquakes, especially those larger than magnitude 6.0, are rare. The largest events, a magnitude 6.9, struck in 1980 and killed 600 people.

San Miguel has few natural bodies of water and a number of smaller streams and rivers that flow outwards from the Sierra del Fuego. Many of these lakes are located in the Sierra del Fuego, and are either formed as crater lakes, from landslides that have dammed streams and rivers, or as reservoirs extending behind hydroelectric dams. The largest natural body of water in San Miguel is the Lago de Dios in the El Altar Massif in southern San Miguel, with the lake being five square kilometres in size. It is technically a twin lakes complex, divided between the Lago Verde and Lago Azul. The largest man-made lake is the Reservorio Eduardo Gutiérrez, which is ten square kilometres in size, and occupies much of the Valle del Corvos in northwestern San Miguel. Most watercourses in San Miguel are small streams, although a number of larger rivers can be found. The largest and longest of these is the Tesejerague, which flows for 123 kilometres through southern San Miguel, including the capital, Laguira.

- Landscapes of San Miguel

Lago de Dios in the El Altar Massif

Climate

The climate of San Miguel is influenced by three primary factors; the warm Bahian Current which runs up the east coast of Bahia and Rahelia and between San Miguel and x, the Vehemens Ocean, and the proximity to continental Coius. Because of this, the island has one of the more northerly subtropical climates, which varies by location and altitude.

The western side of the island is dominated by a humid subtropical climate that broadly resembles that of a wetter Solarian Sea climate, with two seasons. Between October and March, the climate is cool with higher rainfall, peaking around the months of the northern winter. April through September becomes drier and warmer, with the hottest months occuring during the northern summer. Early summer can cause temperature differences that result in the western part of the island covered in fog or cloud, and the eastern half clear and sunny. Summers usually see between three and four days where temperatures peak above 30°C. In addition to being warmer, the western side is also slightly wetter than the eastern side. Southern San Miguel, particularly south of the El Altar Massif and along the southern coast, is also affected by this variant of the humid subtropical climate.

Eastern San Miguel by comparison is influenced by the Vehemens Ocean and less influenced by the Bahian Current. The eastern side is cooler and slightly less wetter, with temperatures on the east side remaining around 1°C less on average than elsewhere. Average temperatures are enough to qualify the climate in the east of San Miguel to border on oceanic, especially in the north of the country.

The southern third of the island lies at the northwestern extremity of the North Vehemens Tropical Impact Zone, an area of coast around the periphery of the Vehemens Ocean north of the equator where tropical cyclones make landfall routinely. Most of them are either tropical storms or remnants of these cyclones, which still bring powerful winds and heavy rainfall.

The highest recorded temperature in San Miguel is 38.2°C, observed in Guelelita on September 17, 1985. The lowest temperature is -3.6°C, recorded at Puerto Nieblo on January 22, 1973.

Environment

Much of the island has been significantly altered in terms of vegetation, with approximately x of the island either urbanised or converted into non-native vegetation, especially forestry blocs and plantations, all of which has occurred since the arrival of humans.

The dominant native biome is the laurisilva forests that once dominated most of the island, and are typically found at elevations of between 400 and 1,200 metres above sea level. Archaeological evidence suggests that these forests on the island have been in existence for 1.8 million years. Dozens of species of plants exist within the forest, some of which are endangered. Once covering a third of the island, today only 4,417 square kilometres of these forests remain in various patches around the island, most of which in protected national or local parks.

Lower elevations typically consisted of shrublands on both sides of the Sierra del Fuego, although much of these were destroyed to make room for farmland and urban growth. These were among the most extensive biomes found on the island, and extended down to sea level in some areas. This is where the majority of San Miguel's endemic species, especially reptiles, were found. Today less than a fifth of these shrublands remain intact, much of it in protected areas.

Beyond the laurel forests in the Sierra del Fuego lie the high altitude pine forests composed entirely of endemic confiers, these being the San Miguel pine, and the San Miguel cedar. These are found at altitudes of between 1,000 and 2,100 metres above sea level, with an alpine tree line below that of continental equivalents. A number of species of birds and mammals exist within this biome, including endemic and introduced species.

San Miguel is home to over 50 species of mammals, over 100 species of birds and, over 30 species of reptiles, many of which are endangered, with numerous species of introduced mammals, birds, and reptiles. Among the endemic species to the islands include the national bird, the blue chaffinch and the national reptile, the San Miguel lizard. Both of these can be found around the island, alongside other native bird and reptile species, the latter of which have the most species listed as endangered or critically endangered.

San Miguel has significant problems with introduced species, particularly rodents, feral cats, and mustelids, and has engaged in widespread pest control operations using a variety of methods. For less destructive species, management has been key in limiting the spread of invasive species, particularly plant species such as the hydrangea which are well liked on the island. There are also issues with farmers encoraching on protected areas and non-protected patches of native forests and scrubland to graze livestock, with the government actively working with rural communities to manage land.

Government

San Miguel is classified as a presidential republic, with an elected president and legislature. It also possesses an independent judicial system, although certain judges are appointed to positions in the Supreme and Constitutional Courts by the President. San Miguel ranks highly in transparency as well as freedom of the press and political freedoms.

Constitution

The Constitution of San Miguel is the document which outlines the roles of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, the independence of each branch, as well as the powers of central and local government.

The Constitution of San Miguel was drafted after the local government declared independence from Auratia on October 7, 1927, and was completed in 18 months. However, it was not implemented due to the outbreak of the Great War and the threats posed by the Entente to the island and its government, which ruled the country through emergency legislation and powers. These were lifted in January 1936, and the constitution was formally ratified on Februrary 14 of that year.

The constitution outlines the independence of all three branches of government, and reiterates that each has a role in overall government accountability. It mandates independence of government agencies that enforce laws, and the independence of all courts that apply them. It also outlines cooperation between central and local governments over certain matters, such as transport, conservation, and heritage.

In addition to defining government powers, the Constitution of San Miguel also protects the rights and civil liberties of the citizens of the republic. It guarantees multiple freedoms as well as protections from discrimination, including discrimination on the basis of sex, racial or ethnic background, and religion.

Amendments to the constitution are made through the National Congress and through the Constitutional Court. An amendment is voted on in Congress to be passed onto the Constitutional Court for review, before being approved or rejected, and then passed back to Congress for changes or a final vote to ratify the amendment.

Legislature

The National Congress of San Miguel is the unicameral legislature of San Miguel. It is composed of exactly 100 members, and is colloquially referred to as Los Cien, or "The One Hundred".

The National Congress is primarily concerned with the creation, deliberation, and ratification, of legislation and constitutional amendments. In this respect, the National Congress has the power to pass laws with executive approval, as well as approve the national budget, and any executive orders from the President. The National Congress is also a part of the system of checks and balances that holds the President and the Cabinet of Minister to account.

Requirements to be elected to the National Congress include San Miguelan citizenship, to be 18 years of age on the day of the election, and not to have served time in prison. They must also pass a physical and mental health examination, and be deemed mentally competent to stand for office. In addition, they must also pass a literacy test.

President

The President of Republic of San Miguel is the executive branch of government, with the office combing the roles of a head of state and head of government. The office was created upon the declaration of independence in 1927 although its role was not defined until after the ratification of the Constitution.

The roles and powers of the President are outlined in two sections of the Constitution. Section Six states that the President shall sign passed legislation into law, and possesses the right of veto to be affirmed or denied by the Constitutional Court. They have the power to call elections, dissolve the National Congress, to award pardons for prisoners, to issue executive orders, to declare war on a foreign nation, to appoint and dismiss members of the Cabinet of Ministers, the Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court, the Central Bank of San Miguel, as well as other important positions. Section Seven states that the President's role is the supreme diplomat of the Republic of San Miguel, and can sign treaties and agreements in the name of the Republic and its citizens.

Section Seven also states that the President must possess the same requirements as other candidates for office in San Miguel. However, the President faces additional limitations, including a requirement to be 30 years of age or more, serve at least ten years in the National Congress, and have held a cabinet post.

Elections

Elections in San Miguel are overseen by the National Election Commission (CEN), a government agency of the Ministry of the Interior. The role of the CEN is to organise and oversee local and national elections, vet potential candidates for local and national elections, and provide advice to the government on electoral law. The organisation is headed by the Commissioner of Elections, who is appointed to the role by the Minister of the Interior.

Elections are required to be held in San Miguel every four years, and elected politicians can serve as many terms as they wish, save for the President, who can be elected to a maximum of three terms. Four year terms are standard across both national and local elections.

The voting system used in San Miguel is the single transferable vote system whereby candidates are ranked according to preference. There are sixteen electorates across the country, each with as close as possible to an even population number within electoral boundaries. Each electorate contains six seats, and those seats are filled with voter preferences until all seats are filled. In addition, there are four additional seats outside of the electorates to represent the San Miguelans living overseas.

Candidates for presidential elections are selected through closed primaries, where registered members of political parties from each of San Miguel's 16 parish vote for their preferred candidate within the party. Those votes go to delegates who are legally mandated to vote for the candidate who received the most votes in their parish. This system is used by most parties in San Miguel who have enough registered members for a delegate system to work.

Judiciary

The judiciary of San Miguel is independent from both the executive and legislative branches of the government and is largely administered by the Ministry of Justice. The court system in San Miguel is divided into general courts, administrative courts, and appeals courts. San Miguel is a civil law jurisdiction, and all legislation passed by the National Congress is present in the country's Civil Code. Trial by jury is guaranteed under Section 17 of the Constitution.

General courts are the most numerous of their kind in San Miguel and are divided between municipal and parish courts. Municipal courts are largely found in most municipalities although some also extend over rural areas with sparse populations. Their role is to hear minor cases, such as traffic infringements, as well as settle smaller disputes. Parish courts are found in each of the 16 parishes in San Miguel and hear a variety of cases, from murder trials and high profile criminal cases, to the family court system.