Weranian Unification: Difference between revisions

Britbong64 (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (102 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[ | {{featured_article}} | ||

'''Weranian Unification''', known in [[Werania]] as simply the | {{KylarisRecognitionArticle}} | ||

{{Infobox historical era | |||

|name = Weranian Unification | |||

|start = 1801 | |||

|end = 1856 | |||

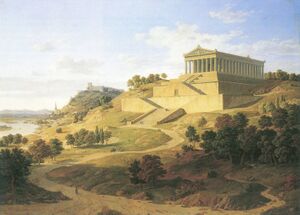

|image = Hall of the Fatherland.jpg | |||

|caption = The Hall of the Fatherland, a monument celebrating Weranian figures throughout history built to celebrate unification. | |||

|before = [[Weranian Revolution]] | |||

|including = {{hlist|[[1828 Weranian revolution]]|[[Weranian War for Unification]]|[[War of the Triple Alliance]]|[[Easter Revolution]]}} | |||

|after = [[Prachtvolle Epoche]] | |||

|monarch = [[Rudolf IV of Werania|Rudolf IV]], [[Adalbert of Werania|Adalbert]] | |||

|leaders = [[Urmas Kask-Jakobson]], [[Ulrich von Bayrhoffer]], [[Sebastian Mertz]] | |||

}} | |||

{{Template:History of Werania}} | |||

'''Weranian Unification''', known in [[Werania]] as simply the '''Einigung''', was the process in which the previous divided kingdoms and city-states of the Weranian lands became the modern nation state of the Weranian Confederation which was declared on the 17<sup>th</sup> March 1842. The process is believed to have started with the [[Weranian Revolution of 1828]] although has its roots in the [[Weranian Revolution|1785 revolution]] that had led to the dissolution of the [[Rudolphine Confederation]] and the creation of the [[Weranian Republic]]. | |||

Inspired by a mixture of notions including {{Wp|nationalism}}, {{wp|historical revisionism}}, {{wp|republicanism}}, {{wp|liberalism}}, {{wp|secularism}} and {{wp|democracy}} the impetus for Weranian unification following the republic's dissolution led to the start of the "Weranic Question" of whether a state for the Weranian people should emerge, if it should be a {{Wp|republic}} or {{wp|monarchy}} and if it only consist of | Inspired by a mixture of notions including {{Wp|nationalism}}, {{wp|historical revisionism}}, {{wp|republicanism}}, {{wp|liberalism}}, {{wp|secularism}} and {{wp|democracy}} the impetus for Weranian unification following the republic's dissolution led to the start of the "Weranic Question" of whether a state for the Weranian people should emerge, if it should be a {{Wp|republic}} or {{wp|monarchy}} and if it only consist of {{wp|High German|Weranian}} speaking lands or be enlarged to those who spoke common Weranic languages. During the early 19th century these questions led to an outpouring of nationalist activity in the Weranic states notably through the revolutionary secret society, the [[Septemberists]]. | ||

By 1829 republican nationalists united with monarchists in the Kingdom of [[Cislania]] to jointly promote the cause of unification. Gaining the support of [[Estmere]] these liberal nationalists began to see | By 1829 republican nationalists united with monarchists in the Kingdom of [[Cislania]] to jointly promote the cause of unification. Gaining the support of [[Estmere]] these liberal nationalists began to see [[Kirenia]] as the biggest obstacle to unification. From 1836 starting with the [[Septemberist Revolt]] in Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken to the 1841-42 [[Weranian War of Unification]] the pace of unification under the Cislanian banner rapidly increased with the Weranian Confederation being declared following the victory of Cislanian forces in 1842. The state further expanded with the [[Easter Revolution]] in the eastern Weranian states. | ||

The final act of Weranian unification was the [[War of the Triple Alliance]] fought between Werania and [[Estmere]] against | The final act of Weranian unification was the [[War of the Triple Alliance]] fought between Werania and [[Estmere]] against Kirenia, [[Gaullica]] and [[Soravia]]. Although the war had intended to unite the rest of the Weranic lands in Kirenia - considered to be the entirely Weranic speaking east marches and partially Weranian speaking Ruttland - into Werania, it failed to do so with Werania acquiring Ruttland alone. However the war did result in the survival of a unified Weranian nation confirming its presence permanently in [[Euclea]]. | ||

Weranian unification is considered to have changed the {{wp|balance of power}} in [[Euclea]]. It represented a decline in | Weranian unification is considered to have changed the {{wp|balance of power}} in [[Euclea]]. It represented a decline in Kirenia and [[Solstiana]] whilst the creation of a unified Werania introduced a new {{Wp|great power}} on the continent that would compete with Gaullica, Soravia, Estmere and [[Etruria]] for influence. Weranian unification is still celebrated in Werania despite there still being debate as to whether its primary protagonists - [[Rudolf VI of Werania|Rudolf VI]] and [[Ulrich von Bayrhoffer]] - intended to unify Werania or whether unification was the result of ''ad hoc'' agreements pursued out of pragmatism and opportunism. | ||

==Brief Timeline== | ==Brief Timeline== | ||

*1785 - The [[Weranian Revolution]]. The Rudolphine Emperor [[Leopold III, Rudolphine Emperor|Leopold III]] is overthrown by republicans and Weranic nationalists who declare the [[Weranian Republic]]. The revolution quickly spreads across the Confederation until the republicans are victorious creating a national convention under the leadership of the [[Brotherhood for the Rights of Man]] who supported a centralised republican state based on the [[Cult of Rationalism]]. | *1785 - The [[Weranian Revolution]]. The Rudolphine Emperor [[Leopold III, Rudolphine Emperor|Leopold III]] is overthrown by republicans and Weranic nationalists who declare the [[Weranian Republic]]. The revolution quickly spreads across the Confederation until the republicans are victorious creating a national convention under the leadership of the [[Brotherhood for the Rights of Man]] who supported a centralised republican state based on the [[Cult of Rationalism]]. | ||

*1789 - The republic after internal instability is embroiled in conflict with [neighbours]. [[Balthasar Hötzendorf]] is elected {{wp|generalfeldmarschall|commander of the revolutionary armies}} by the National Diet ushering in a period of {{Wp|Bonapartism|militarised republicanism}}. | *1789 - The republic after internal instability is embroiled in conflict with [neighbours]. [[Balthasar Hötzendorf]] is elected {{wp|generalfeldmarschall|commander of the revolutionary armies}} by the National Diet ushering in a period of {{Wp|Bonapartism|militarised republicanism}}. | ||

*1801 - The Weranian Republic is dissolved after [[ | *1801 - The Weranian Republic is dissolved after [[Kirenia]], [[Kingdom of Estmere|Estmerish]] and [[Soravian Empire|Soravia]] defeat it militarily. Its replacement however is far more truncated then the former states in the Rudolphine Confederation with seven kingdoms and two free cities being created. | ||

*1816 - The Central Revolutionary Federation commonly simply known as the [[Septemberists]] (Septembristen) is founded in | *1816 - The Central Revolutionary Federation commonly simply known as the [[Septemberists]] (Septembristen) is founded in Gothberg. A network of {{Wp|secret society|secret revolutionary societies}} the Septemberists would become one of the most influential groups agitating for Weranian unification based on a republican model. | ||

*1821 - Bloody Summer. A series of liberal insurrections across the Weranian states. Most are small scale and ineffective, but notably a liberal revolution in Cislania leads King [[Rudolf VI of Werania|Karl | *1821 - Bloody Summer. A series of liberal insurrections across the Weranian states. Most are small scale and ineffective, but notably a liberal revolution in Cislania leads King [[Rudolf VI of Werania|Karl Rudolf]] to promulgate a constitutional monarchy, the first of its kind in the Weranic states. | ||

*1828 - The [[Weranian Revolution of 1828]]. Septemberist republicans raise up across Werania. A second republic is declared in Westbrücken, the heart of the pan-Weranic movement. The revolts are crushed with | *1828 - The [[Weranian Revolution of 1828]]. Septemberist republicans raise up across Werania. A second republic is declared in Westbrücken, the heart of the pan-Weranic movement. The revolts are crushed with Kirenian and Estmerish assistance but the strength of pan-Weranicism is reaffirmed. There is also a shift in the central thrust of pan-Weranicism from republicanism to cooperation with the liberal monarchy of Cislania. During the revolution there is the appointment of [[Ulrich von Bayrhoffer]] as Minister-President of Cislania and the rise of the [[Pan-Weranic Party]] in the Kingdom. Reconciliation begins between the Cislanian monarchy and the Septemberists over the pan-Weranic cause. | ||

*1836-1837 - The [[Septemberist Revolt]] in Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken, then in a {{wp|personal union}} with the [[Kingdom of Solstiana]]. The Septemberists supported by Cislania lead a successful uprising against the unpopular isolated regime in the region, with a {{wp|Free state (polity)#Germany|free state}} being declared. King Karl Rudolf is invited to serve as king in a {{wp|personal union}}. This initiates the [[Cislanian-Solstianan War]]. In response to the Septemberist Revolt the [[Kingdom of Solstiana]] demands Cislania end the personal union with Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken which leads to war between the two nations which ends with a {{wp|status quo antebellum}} after Werania is able to confirm Estmerish particupation. | |||

*1836 - The [[Septemberist Revolt]] in Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken. The Septemberists supported by Cislania lead a successful uprising against the unpopular | *1841-1842 - [[Weranian War of Unification]]. Cislania and Prizen declare war on a coalition of Roetenberg, Wiittislich, Elbenweis and Westbrücken, considered to be in the Kirenian {{wp|sphere of influence}}. Werania wins against them with nominal assistance from Estmere. The Treaty of Frankendorf sees the creation of the Weranic Confederation which also includes Roetenberg, Wiittislich and Elbenweis with Westbrücken being named the federal capital. Karl Rudolf becomes head of state with the regal name of Rudolf VI. | ||

*1843 - The Eastern Annexations. A nationalist revolution in Wolfsfled leads to the King of Wolfsfled to invite Weranian troops into the country in order to put down the rebellion in return for a referendum on joining the confederation. Wolfsfled votes in favour of joining and shortly afterwards Kolreuth also acceded to the confederation.. | |||

* | *1852-1855 - The [[War of the Triple Alliance]]. Werania issues an ultimatum to Kirenia to surrender its Weranic regions. This leads to the War of the Triple Alliance between Werania and Estmere against Kirenia, Soravia and [[Gaullica]] that ends with [[Ruttland]] being ceded to Werania after Estmero-Weranian forces largely prevail over the Triple Alliance. | ||

* | *1856 - The [[Easter Revolution]]. A failed republican-socialist revolt is put down after the War of the Triple Alliance results in less land being ceded to Werania then was promised prior to the war. The suppression of the revolutionaries largely leads to the end of revolutionary and pan-Weranicist movements in the Weranian states and is considered to be the endpoint of the unification period. | ||

*1852-1855 - The [[War of the Triple Alliance]]. Werania issues an ultimatum to | |||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| Line 30: | Line 42: | ||

The most prominent revolutionary faction was the [[Brotherhood for the Rights of Man]] who were inspired by the revolutions in Rayenne and Etruria. The Brotherhood followed the [[Cult of Rationalism]] (''Kult der Rationalismus'') that amongst other things emphasised {{wp|republicanism}}, {{wp|centralisation}}, {{wp|rationalism}}, intense {{wp|anti-clericalism}} and {{wp|militarism}} calling for the mobilisation of vast citizen-armies based on republican virtue. Although the Brotherhood and their supporters were more informed by republican and rationalist discourse their emphasis on citizens rather then subjects, use of the Weranian language, attacks on both the Catholic and Amendist churches and centralising reforms created a national identity based around the Weranic language and history. | The most prominent revolutionary faction was the [[Brotherhood for the Rights of Man]] who were inspired by the revolutions in Rayenne and Etruria. The Brotherhood followed the [[Cult of Rationalism]] (''Kult der Rationalismus'') that amongst other things emphasised {{wp|republicanism}}, {{wp|centralisation}}, {{wp|rationalism}}, intense {{wp|anti-clericalism}} and {{wp|militarism}} calling for the mobilisation of vast citizen-armies based on republican virtue. Although the Brotherhood and their supporters were more informed by republican and rationalist discourse their emphasis on citizens rather then subjects, use of the Weranian language, attacks on both the Catholic and Amendist churches and centralising reforms created a national identity based around the Weranic language and history. | ||

The revolutionaries was early on wracked by internal troubles and tensions on its borders with [[ | The revolutionaries was early on wracked by internal troubles and tensions on its borders with [[Kirenia]] and [[Kingdom of Estmere|Estmere]], but conflict was avoided with the prospect of the revolutionaries restoring the former Emperor albeit as a {{wp|constitutional monarch}}. However in April 1786 the former Emperor Leopold III led the [[Weranian Revolution#March of the 100|March of the 100]], an unsuccessful attempt to restore the monarchy to its full power. The former Emperor was imprisoned by the revolutionaries who on the 5 May declared the [[Republic of Werania]] formally ending the monarchy. The new republican government was soon dominated by [[Franz Xaver Dobrizhoffer]] and [[Sigmund Auerswald]], considered to be the chief ideologues behind the Cult of Rationalism. The diarchy ordered the execution of the royal family and the mobilisation of citizen armies to defend the revolution against the neighbouring powers. This started the North Euclean Revolutionary Wars which pitted the republic against its neighbours as breakdowns in diplomacy between the traditional powers and the republic spiralled into war. The revolutionary armies often secured military successes thanks to the meritocratic officer promotions, the loyalty and devotion of troops to the Weranian Republic and the mass mobilisation of men via the {{wp|Levée en masse|massenaushebung}}. | ||

In 1789 [[Balthasar Hötzendorf]] was elected as {{wp|generalfeldmarschall}} of the revolutionary armies transitioning the republic to one based on {{wp|Bonapartism|militarised authoritarianism}} as much as the Cult of Reason, with Hötzendorf increasingly controlling the political nature of the republic. The constant war with Werania's neighbours made Weranian society incredibly militarised which necessitated the continued deployment of nationalist and revolutionary rhetoric. | In 1789 [[Balthasar Hötzendorf]] was elected as {{wp|generalfeldmarschall}} of the revolutionary armies transitioning the republic to one based on {{wp|Bonapartism|militarised authoritarianism}} as much as the Cult of Reason, with Hötzendorf increasingly controlling the political nature of the republic. The constant war with Werania's neighbours made Weranian society incredibly militarised which necessitated the continued deployment of nationalist and revolutionary rhetoric. | ||

[[File:Johann Peter Krafft 003.jpg|thumb|250px|[[Balthasar Hötzendorf]] leading Weranian troops during the [[Battle of Longswood]].]] | [[File:Johann Peter Krafft 003.jpg|thumb|250px|[[Balthasar Hötzendorf]] leading Weranian troops during the [[Battle of Longswood]].]] | ||

As a result of the citizen armies, expansion of citizen's rights and constant atmosphere of revolutionary fervour nationalism amongst Weranic's flourished under the republic in a way the republic's rivals could not match. The role of | As a result of the citizen armies, expansion of citizen's rights and constant atmosphere of revolutionary fervour nationalism amongst Weranic's flourished under the republic in a way the republic's rivals could not match. The role of Kirenia as an enemy of the revolution was particularly important in nationalist discourse; propagandists within the republic soon promoted the notion that the Kirenian monarchy was an oppressive force to the Weranic people of the nation and promoted the idea of dissolving the Kirenian state and annexing large sections into Werania on the basis of republican values and linguistic and cultural unity. Hötzendorf bemoaned the lack of Weranic unity prior to the revolution as being an un-rational, illogical state of affairs and stated that a unified state based on the power of the "natural citizenry" of Werania was necessary to rationalise Euclea's political boundaries. | ||

However the military successes of the republic led to a coalition to form against the republic consisting of Estmere, | However the military successes of the republic led to a coalition to form against the republic consisting of Estmere, Kirenia and Soravia who feared the republic's radical ideals and wished to permanently divide the Weranic lands so they did not pose a threat to the balance of power in northern Euclea. From 1799 to 1801 the republic suffered several catastrophic defeats and by March 1801 the republic formally surrendered after Kirenian forces occupied Westbrücken, ending the Weranian revolution and the republic as a whole. | ||

===Partition of the Republic=== | ===Partition of the Republic=== | ||

With the defeat of the republic the leaders of | With the defeat of the republic the leaders of Kirenia, Estmere and Soravia met at the Kirenian city of Harimisaareke to discuss the partition of the Weranian Republic. The republicans had executed a substantial amount of nobles from the old Rudolphine Confederation, most prominently the majority of the house of Brücken who had ruled the confederation since the end of the [[Amendist Wars]]. As a result it was decided that the old confederation would not be restored in its entirety and that a new patchwork of states, partially based on the old system, would be created. | ||

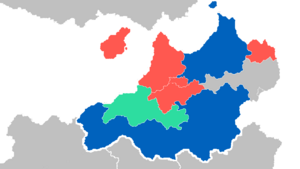

The new division was seen to benefit | The new division was seen to benefit Kirenia who gained influence over the Weranic states. The House of Pühatera retained power in the Grand Duchy of Wolfsled whilst the restored Kingdom of Roetenberg, Grand Duchy of Prizen, Duchy of Elbenweis and Free City of Westbrücken were under informal Kirenian influence. The eastern states of Wolfsfled, Duchy of Wittislich and Free City of Kolreuth were also considered to be aligned with Kirenia, although less strongly then the former states. The Kingdom of Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken continued its {{Wp|personal union}} with the newly-formed Solstanian state whilst the Kingdom of Cislania was seen as friendly with Estmere. Although the majority of the new states were aligned with Kirenia the partition strongly favoured Cislania which emerged larger then it had been under the old confederation. | ||

[[File:Preunification werania.png|thumb|The map of the Weranic states following the dissolution of the Republic.|350px|left]] | [[File:Preunification werania.png|thumb|The map of the Weranic states following the dissolution of the Republic.|350px|left]] | ||

One important change that came from the republic's partition and creation of new states was the doctrine that the | One important change that came from the republic's partition and creation of new states was the doctrine that the personal unions that had been common in the Rudolphine era would be increasingly reduced. The [[Emperor of Soravia]] which through the House of Ryksmark-Halte-Herdorf had held personal union with Wittislich surrendered the post of king of Wittislich to his brother. The intention of this was to prevent Kirenia asserting potential personal unions with Weranic states that would threaten the position of Estmere in the region. The exception was Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken's personal union with Solsitania, due to Solsitania being seen as a neutral buffer by Kireania and Estmere. | ||

The new states were largely conservative in character. Wolfsfled was the sole monarchy that possessed a constitution which restricted suffrage to property owning males. Although the free cities of Westbrücken and Kolreuth were more liberal in character they still were governed by reactionaries who rejected Weranian nationalism, being under the heavy influence of their larger neighbours. Although liberal groups - particularly nationalist-minded students - lobbied for nationalist causes the rulers of the Weranian states largely created {{Wp|police states}} that imposed press censorship and attempted to reverse many of the gains made by the revolution. | The new states were largely conservative in character. Wolfsfled was the sole monarchy that possessed a constitution which restricted suffrage to property owning males. Although the free cities of Westbrücken and Kolreuth were more liberal in character they still were governed by reactionaries who rejected Weranian nationalism, being under the heavy influence of their larger neighbours. Although liberal groups - particularly nationalist-minded students - lobbied for nationalist causes the rulers of the Weranian states largely created {{Wp|police states}} that imposed press censorship and attempted to reverse many of the gains made by the revolution. | ||

| Line 50: | Line 62: | ||

===Weranian Question=== | ===Weranian Question=== | ||

An important issue surrounding Weranian nationalist both during and after the dissolution of the republic was what constituted the Weranian nation. Under the republic such a proposition remained divisive - some within the Cult of Rationalism advocated "natural borders" that would've stretched from the Selmrer river in Estmere to the Sweta river in | [[File:Weranic world.png|thumb|The Weranian lingustic world in 1810. | ||

{{legend|#13662C|{{wp|High German languages|Upper Weranic}}}} {{legend|#1B8D3D|{{wp|Central German|Middle Weranic}}}} {{legend|#1FA346|{{wp|Low German|Aldman}}}} {{legend|#2BD75F|Other Weranic languages}}|300px]] | |||

An important issue surrounding Weranian nationalist both during and after the dissolution of the republic was what constituted the Weranian nation. Under the republic such a proposition remained divisive - some within the Cult of Rationalism advocated "natural borders" that would've stretched from the Selmrer river in Estmere to the Sweta river in Kirenia, taking up most of northeast Euclea. Such a proposal was based less on nationalist or linguistic grounds but on the notion of rationalising borders around geographic features that would be centred around what was seen as the superior rationalist culture of Werania. | |||

The notion of natural borders was however rejected by {{wp|romantic nationalism|romanticists}} who came to become more influential in nationalist circles following the defeat of the republic. Romantic nationalists emphasised the unity of the Weranian people both through a shared sense of history stemming from the Rudolphine Confederation but must importantly through the {{wp|German language|Weranic language}}. The development of common {{wp|folklore}} and {{wp|national epic}}s in Weranic became paramount for nationalists. | The notion of natural borders was however rejected by {{wp|romantic nationalism|romanticists}} who came to become more influential in nationalist circles following the defeat of the republic. Romantic nationalists emphasised the unity of the Weranian people both through a shared sense of history stemming from the Rudolphine Confederation but must importantly through the {{wp|German language|Weranic language}}. The development of common {{wp|folklore}} and {{wp|national epic}}s in Weranic became paramount for nationalists. | ||

Simply deciding that the Weranian nation was based on language however was a tricky proposition. The Weranic language was poorly defined between what were dialects and fully-fledged languages. The {{wp|High German languages| | Simply deciding that the Weranian nation was based on language however was a tricky proposition. The Weranic language was poorly defined between what were dialects and fully-fledged languages. The {{wp|High German languages|Upper Weranic}}, particularly the {{wp|Upper German|Afuran Weranic dialects}} was commonly accepted as the mainstay of the Weranic language. Middle Weranic was spoken across the entirety of modern day Werania alongside eastern Kirenia with these areas considered to be part of the "core" of the Weranic state. Outside these regions, delineating the Weranic language was more tricky. {{wp|Low German|Aldman}}, spoken in modern-day [[Alsland]], southern Werania, north [[Estmere]] and northern [[Borland (Kylaris)|Borland]] was considered to be related to the Weranic languages but there was fierce debate by nationalists of whether it was truly Weranic. Similar debates applied to {{wp|Dutch language|Hennish}} (spoken in northern [[Gaullica]]) {{wp|Frisian language|Dellish}} (spoken in Alsland) and [[Azmaran language|Azmaran]] (spoken in [[Azmara]]). The debate of whether these were part of the Weranian nation animated debates on what were "Weranic". More extreme nationalists also debated whether {{wp|English language|Estmerish}}, {{Wp|Anglish|Swathish}} or {{wp|Norwegian language|Solstianan}} counted, although they were generally marginalised. | ||

Another precedent for the extent of the Weranic nation rested on the former borders of the Rudolphine Confederation and earmarked historical holdings such as [[Ruttland]]. The "Weranian Question" thus became whether these non-Weranic areas should be included within Werania, and how strict should the application of determining the Weranic language be in such a case. Those who supported a "Greater Werania" (''Großostischland'') often supported including languages such as | Another precedent for the extent of the Weranic nation rested on the former borders of the Rudolphine Confederation and earmarked historical holdings such as [[Ruttland]]. The "Weranian Question" thus became whether these non-Weranic areas should be included within Werania, and how strict should the application of determining the Weranic language be in such a case. Those who supported a "Greater Werania" (''Großostischland'') often supported including languages such as Swathish, Aldman and Hennish under the Weranic umbrella as well as annexing non-Weranic areas under the logic of creating "living space" for Weranians (''{{Wp|lebensraum}}''). Conversely, those who supported a "Lesser Werania" (''Kleinostischland'') supported a Werania more closely based around Middle Weranic alone and the general creation of a more homogeneous state on the basis of it being more in line with creating a {{wp|nation state}} rather then a ''de facto'' multi-ethnic empire. The Weranian Question would therefore influence the course of unification and the political debates held by its protagonists. | ||

==Early nationalist activity== | ==Early nationalist activity== | ||

| Line 66: | Line 80: | ||

===Secret societies and the Septemberists=== | ===Secret societies and the Septemberists=== | ||

Following the fall of the republic the dominant strand of pan-Weranicism was associated with republicanism. Conservatives largely called for a return of the pre-revolutionary social system whilst moderates were largely content with the new status quo. As the new states carved out in 1801 were by and large {{wp|police states}} that suppressed dissent the republican movement took on largely revolutionary themes and were often {{wp|secret societies}}. These secret societies often based themselves off the Brotherhood for the Rights of Man and were often made up of a network of students, middle-class professionals and businessmen and some intellectuals. | Following the fall of the republic the dominant strand of pan-Weranicism was associated with republicanism. Conservatives largely called for a return of the pre-revolutionary social system whilst moderates were largely content with the new status quo. As the new states carved out in 1801 were by and large {{wp|police states}} that suppressed dissent the republican movement took on largely revolutionary themes and were often {{wp|secret societies}}. These secret societies often based themselves off the Brotherhood for the Rights of Man and were often made up of a network of students, middle-class professionals and businessmen and some intellectuals. | ||

| Line 74: | Line 87: | ||

===Neo-Rudolphinists=== | ===Neo-Rudolphinists=== | ||

Whilst republicans remained the mainstream within the Weranic nationalist movement, there were others who were willing to work within the post-republic structure to advance the course of Weranian unification. Known as the [[Neo-Rudolphinism|neo-Rudolphinists]] due to their praise of the Rudolphine Confederation over the republic these were circles of intellectuals, aristocrats, journalists and businessmen that called for a moderate solution for the unification of Werania by emphasising reformist policies and cooperation with the ruling dynasties and princes of the region. Predominantly {{Wp| | Whilst republicans remained the mainstream within the Weranic nationalist movement, there were others who were willing to work within the post-republic structure to advance the course of Weranian unification. Known as the [[Neo-Rudolphinism|neo-Rudolphinists]] due to their praise of the Rudolphine Confederation over the republic these were circles of intellectuals, aristocrats, journalists and businessmen that called for a moderate solution for the unification of Werania by emphasising reformist policies and cooperation with the ruling dynasties and princes of the region. Predominantly {{Wp|Liberal Catholicism|Catholic liberals}} the neo-Rudolphinists hoped that they could create a {{wp|dual monarchy}} of [[Kirenia]] and a unified Werania that would through the development of a common culture eventually become dominated a homogeneous Weranian ruling class. The neo-Rudolphinists hoped the common Catholic heritage of the region alongside the threats of Soravia and Estmere would help encourage the Kirenian Weranic nobility to abandon their pretensions of a non-Weranic state and rule instead over the Weranic lands. | ||

The neo-Rudolphinists were controversial amongst Weranian nationalists for their approach. Republicans saw cooperation with | The neo-Rudolphinists were controversial amongst Weranian nationalists for their approach. Republicans saw cooperation with Kirenia as a doomed endeavour seeing Kirenian Weranic nobles as being unredeemedly {{wp|Finnicization|Kirenicised}} and more generally rejected a monarchist Werania in principle. Other nationalist, particularly Amendists, saw the inclusion of Kirenia into a Weranian state as a betrayal of the nationalist cause due to the presence of so many non-Weranic people's within the country, particularly with the "''dual monarchy, dual culture''" approach. The Weranian nationalist writer Christopher Schönlein stated that the Kirenian Weranic nobility was "''tainted by the blood and tongue of the lesser''" and that a united Werania had to be based around Weranic-speaking people only. Liberals also rejected a confederal-monarchist Werania on the grounds of the absolutist nature of the governments of the region. Similarly, the Kirenian Weranic nobility often were at ease with their Kirenian counterparts and saw Weranian nationalism as threatening to their own positions as well as encouraging Kirenian nationalism that would destroy their civilisation. Others questioned whether eastern Kirenia was truly Weranic - although the region mostly spoke Weranic languages some linguists questioned whether {{wp|Meuse-Rhenish|Ardenian}} was a dialect of Weranic or a separate language, the latter implication making eastern Kirenia questionably a Weranic society. | ||

Nevertheless neo-Rudolphinists remained influential in certain liberal circles who saw cooperation as the only path for unification of Werania. The neo-Rudolphinists would begin to enter pragmatic alliances with republican forces prior to 1828 with the hope that pressure from below would help lead to a top-down unification led by local monarchs. | |||

===Bloody Summer=== | ===Bloody Summer=== | ||

The imposition of the various {{wp|police state}}s in the Weranic states and their systematic dismantling of the rights and liberties the Republic afforded was resented by many in the intellectual class in Werania and particularly the rapidly growing urban bourgeoisie who saw their economic and social gains reversed with the resurgence in the aristocracy across Werania. Economic growth amongst most of the Weranian states alongside the state of peace that accompanied the end of the republic however meant that the two decades following 1801 were marked by a decline in revolutionary activity as groups such as the Septemberists retreated into the political margins. | The imposition of the various {{wp|police state}}s in the Weranic states and their systematic dismantling of the rights and liberties the Republic afforded was resented by many in the intellectual class in Werania and particularly the rapidly growing urban bourgeoisie who saw their economic and social gains reversed with the resurgence in the aristocracy across Werania. Economic growth amongst most of the Weranian states alongside the state of peace that accompanied the end of the republic however meant that the two decades following 1801 were marked by a decline in revolutionary activity as groups such as the Septemberists retreated into the political margins. | ||

On the 10 July revolutionaries presented Adalbert III with a list of demands that would've created an elected {{wp|landtag}} and civil rights which would've shifted Cislania from an {{wp|absolute monarchy|absolute}} to a {{wp|constitutional monarchy}}. Unwilling to rule as a constitutional monarch but doubtful of his ability to contain the revolutionary fervour | In June 1821 however this period of relative stability came to due to political events that transpired in the largest of the Weranic states, [[Cislania]]. The unpopular monarch [[Franz Joseph II of Cislania|Franz Joseph II]] had presided over an increase in the price of food following tariff increases which had caused uproar amongst the rural peasantry and led to revolutionary activists to increase their dissent to the regime. The dismissal by Franz Joseph II of several university professors at the Imperial Academy of Wiesstadt led to protests in the capital which soon morphed into a general revolutionary movement across Cislania as the {{wp|gendarmerie|national guard}} proved unable to stop discontent with the regime from becoming visible. The revolutionaries had conflicting goals; only a minority of radicals supported the restoration of the republic with the majority calling for the dismissal of corrupt ministers and the granting of civil rights. | ||

[[File:Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841) - The Entrance of George IV at Holyroodhouse - RCIN 401187 - Royal Collection.jpg|thumb|250px|The abdication of [[Franz Joseph II of Cislania|Franz Joseph II]].]] | |||

On the 10 July revolutionaries presented Adalbert III with a list of demands that would've created an elected {{wp|landtag}} and civil rights which would've shifted Cislania from an {{wp|absolute monarchy|absolute}} to a {{wp|constitutional monarchy}}. Unwilling to rule as a constitutional monarch but doubtful of his ability to contain the revolutionary fervour Franz Joseph II abdicated in favour of his son, [[Rudolf VI of Werania|Karl Rudolf]], on the 14 July. Karl Rudolf, who was interested in {{wp|liberalism|liberal}} ideals agreed to adopt the demands in the so-called "July Charter". This precluded an elected Landtag with an electorate of the nobility and upper middle classes; a relaxation of press censorship; and the creation of the post of Minister-President. Elections were held in August which saw a coalition of moderate liberals appointed to power; this made the new King extremely popular and helped dispel unrest in the kingdom as radical groups faded from prominence. | |||

The unrest in Cislania was soon repeated across the other Weranian states. Like with the Cislanian uprising these revolutionary movements were far from united in their causes with some wishing to simply end corruption and improve governance, others to create constitutional rather then absolutist states and others more radical republican goals with the aim of unifying Werania. | The unrest in Cislania was soon repeated across the other Weranian states. Like with the Cislanian uprising these revolutionary movements were far from united in their causes with some wishing to simply end corruption and improve governance, others to create constitutional rather then absolutist states and others more radical republican goals with the aim of unifying Werania. | ||

A series of riots and revolutionary fervour were noted to occur across the Weranic states particularly concentrated in the cities of Westbrücken, Elbdorf, Innsheim, Frankendorf and Obenfelden. The most notable of these responses was in Roetenberg - the Roetenberger King Wilhelm IV wrote to the | A series of riots and revolutionary fervour were noted to occur across the Weranic states particularly concentrated in the cities of Westbrücken, Elbdorf, Innsheim, Frankendorf and Obenfelden. The most notable of these responses was in Roetenberg - the Roetenberger King Wilhelm IV wrote to the Kirenian plenipotentiary for the Weranic states Urmas Kask-Jakobson for guidance on how to deal with the rebellions. Kask-Jakobson recommended a punitive approach and the reaffirmation of conservative, absolutist values stating that if the Weranic kings did not abide by this Kirenia would send its armies to put down the revolts. | ||

As a result the Roetenberger army was deployed to crush the rioters with the other Weranian states following suit. The repressive actions that spanned the months of July and August led to the period to be known as the "Bloody Summer" (''Blutiger Sommer'') due to the intense violence of the repressive measures. Protests were forcibly broken up by force and radical leaders often rounded up, arrested and summarily executed. The states of Roetenberg, Prizen and Elbenweis each passed a series of decrees similar to each other which restricted academic freedom and revolutionary activity. These measures succeeded in the short term in weakening liberal movements but had the unintended side-effect of pushing discontent with the status quo further to the political extremes strengthening the radical Septemberists. | As a result the Roetenberger army was deployed to crush the rioters with the other Weranian states following suit. The repressive actions that spanned the months of July and August led to the period to be known as the "Bloody Summer" (''Blutiger Sommer'') due to the intense violence of the repressive measures. Protests were forcibly broken up by force and radical leaders often rounded up, arrested and summarily executed. The states of Roetenberg, Prizen and Elbenweis each passed a series of decrees similar to each other which restricted academic freedom and revolutionary activity. These measures succeeded in the short term in weakening liberal movements but had the unintended side-effect of pushing discontent with the status quo further to the political extremes strengthening the radical Septemberists. | ||

| Line 96: | Line 110: | ||

===Declaration=== | ===Declaration=== | ||

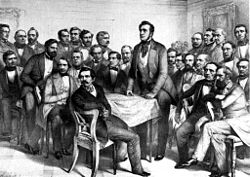

The immediate trigger for the 1828 revolution occurred in the city of Westbrücken which was already considered to be the centre of pan-Weranicist politics. A city prefect, Jonathan Bischof, on the 17 March ordered the execution of three students after they illegally held a speech calling for the end of monarchism in the Weranic states and unification under a republic. Bischof's order caused discontent amongst the city's denizens who protested the execution order and rallied in the streets to support growing calls for an overthrow of the city's conservative government. On the 20 March revolutionaries stormed the Palais Beinhoff and declaring a provisional revolutionary government. | The immediate trigger for the 1828 revolution occurred in the city of Westbrücken which was already considered to be the centre of pan-Weranicist politics. A city prefect, Jonathan Bischof, on the 17 March ordered the execution of three students after they illegally held a speech calling for the end of monarchism in the Weranic states and unification under a republic. Bischof's order caused discontent amongst the city's denizens who protested the execution order and rallied in the streets to support growing calls for an overthrow of the city's conservative government. On the 20 March revolutionaries stormed the Palais Beinhoff and declaring a provisional revolutionary government. | ||

[[File:Paulskirche Casinofraktion.jpg|Wolfram Schlüter and other members of the Septemberists declaring the republic in a Westbrücken beer house.|thumb|250px]] | [[File:Paulskirche Casinofraktion.jpg|Wolfram Schlüter and other members of the Septemberists declaring the republic in a Westbrücken beer house.|thumb|left|250px]] | ||

The revolutions soon spread throughout the Weranian states in a similar manner as to what occurred in 1785 and 1821. In Roetenberg, Elbenweis, Prizen and Wolfslfed the monarchs of those states reluctantly granted constitutions as did the Mayor of Kolreuth making Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken and Wittislich the only Weranian states to lack constitutions. In the new constitutional states provisional governments were formed that became known as the "revolutionary governments". | The revolutions soon spread throughout the Weranian states in a similar manner as to what occurred in 1785 and 1821. In Roetenberg, Elbenweis, Prizen and Wolfslfed the monarchs of those states reluctantly granted constitutions as did the Mayor of Kolreuth making Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken and Wittislich the only Weranian states to lack constitutions. In the new constitutional states provisional governments were formed that became known as the "revolutionary governments". | ||

| Line 102: | Line 116: | ||

On the 15 April the Septemberist leader Wolfram Schlüter declared in a Westbrücken beer house the existence of the [[Weranian Free State]] (''Ostischen Freistaat'') and of a National Diet. Despite pressure from other Septemberists Schlüter did not declare a republic as other revolutionary factions - most notably the neo-Rudolphinists - held out hope that the prince could be persuaded to peacefully unify into a Weranic state through some kind of agreement. | On the 15 April the Septemberist leader Wolfram Schlüter declared in a Westbrücken beer house the existence of the [[Weranian Free State]] (''Ostischen Freistaat'') and of a National Diet. Despite pressure from other Septemberists Schlüter did not declare a republic as other revolutionary factions - most notably the neo-Rudolphinists - held out hope that the prince could be persuaded to peacefully unify into a Weranic state through some kind of agreement. | ||

[[File:Leopold I of Belgium (2).jpg|thumb|250px|[[Cislania|Cislanian]] King [[Rudolf IV of Werania|Karl Rudolf]] was sympathetic to the revolutionaries.]] | |||

The declaration of a free state spurred movements across the remaining Weranic states to discuss the issue of unification. In Cislania King Karl Rudolf announced his government would not stand in the way of the revolutionaries and applauded the "''cause for a Weranian nation''". However the kings of Wittislich and Wolfsfled were more critical pressing the Kirenian plenipotentiary Kask-Jakobson for Kirenia to take action against the revolutionaries. | |||

For Kirenia and Estmere the reactions to the revolutions were different. Following the declaration of the Free State the Esmterish [[Prime Minister of Estmere|Prime Minister]] [[Robert Fitzjames|Robert Fitzjames, the Marquess Moreland]] wrote to King Karl Rudolf to gauge his response. Fitzjames was in contrast to previous Estmerish administrations sympathetic to the cause of Weranian unification, believing that the "''industrious Weranians have as every right a state as any free man''", and saw a united Werania as a potential ally to counterract [[Gaullica|Gaullican influence]], but was alongside the Estmerish King wary of a repeat of the revolutionary violence the republic had unleashed in 1785. Karl Rudolf responded to the Marquess with the promise that Cislania supported the move towards a liberal, constitutional Werania but one "''tempered by moderation, not radicalism''". | |||

In contrast the Kirenian elite were divided. Emperor [[Juahn V of Kirenia|Juhan V]] was opposed to Weranic nationalism but was hesitant to use drastic force to suppress the rebellions; this was in contrast to plenipotentiary Kask-Jakobson who urged the Emperor to deploy the Kirenian army to stamp out the rebellion. Several neo-Rudolphinists in the Kirenian court also sympathised with the revolutionaries and toyed with the idea of inviting Juhan V to take the role as Emperor of the Weranic and Kirenian Lands. | |||

The declaration of a free state | ===Radicalisation=== | ||

As May 1828 emerged the tenuous arrangements between the revolutionary governments and the reluctant constitutional monarchs were breaking down. The declaration of a free state and National Diet had alarmed the monarchs who saw a restoration of the republic imminent but had relented from acting due to the passive attitude of Kirenia to the revolutions and the fear of incurring popular anger by dismissing the revolutionary governments. | |||

With pressure increasing on the revolutionary governments to come to a constitutional arrangement with the monarchies on May 16 the National Diet petitioned the Kirenian Emperor Juhan V to accept the position of Emperor of the Weranics and Kirenians who would be the monarch of the entirety of the Weranic peoples. The neo-Rudolphinists within the revolutionary governments hoped that a Kirenian-led Werania would be an acceptable compromise between the conservative Weranian monarchy and aristocrats and radical revolutionaries as well as garnering recognition from the other Euclean powers. The most prominent neo-Rudolphinist Johann von Glöckner passionately argued to the National Diet that a Kirenian Emperor of Werania was the only way in which a unified Werania would be restored and that the "''Kirenian tounge will be replaced with our noble language in due course''". | |||

{{multiple image | {{multiple image | ||

| align = left | | align = left | ||

| total_width = | | total_width = 375 | ||

| image1 = | | image1 = Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland (1771-1851).jpg | ||

| width1 = 100 | | width1 = 100 | ||

| image3 = | | image3 = Antoine-Henri Jomini.jpg | ||

| width3 = 75 | | width3 = 75 | ||

| footer = | | footer = Emperor Juhan V and plenipotentiary Urmas Kask-Jakobson formulated the Kirenian response to the 1828 revolution. | ||

}} | }} | ||

However the prospect of Juhan V accepting was marginal at best. Whilst some in the Kirenian elite were supportive of the neo-Rudolphinist cause the majority were either firmly supportive of a multi-ethnic Kirenian state or wanted to further Kirenicise the state, not rule over millions of Weranians whose demographic majority would eliminate the Kirenian population. As well as this far from encourage other Euclean powers to accept a unified Werania a Kirenian annexation of the territory was heavily opposed by Estmere who feared becoming encircled by Kirenia and [[Gaullica]]. As such on May 20 Juhan V rejected the petition calling the National Diet "''mad, mad as march hares!''". | |||

Following the rejection by Juhan V the compromising elements of the revolutionary governments lost legitimacy. On May 26 the King of Roetenberg Wilhelm IV dismissed the revolutionary government and attempted to form a cabinet of conservative ministers. This triggered the revolutionary government to mobilise revolutionary militias to storm the royal palaces and declare the abdication of the monarchy on May 28, creating a republic. From May 28 to June 3 these militia's led by the Septemberists repeated this action overthrowing the monarchies in the states that had revolutionary governments (Elbenweis, Prizen and Wolfslfed). This led to the revolutionary government in Westbrücken to declare that the Free State would henceforth be governed on a republican basis and that Werania was "''free from the tyranny that has dominated since 1801''". | |||

The declaration of a republic unleashed a wave of popular revolutionary fervour but also of intense violence has had occurred in 1786 following the March of the 100. The actions of the revolutionaries - and pressure from the now-exiled monarchs - proved decisive when Kask-Jakobson approached Juhan V to use force to put down the "''rebellion of the feeble-minded''". Juhan V exasperated with the actions of the revolutionaries approved Kask-Jakobson's proposal calling up 100,000 men to march on Westbrücken to put down the revolution. | |||

===Suppression=== | ===Suppression=== | ||

[[File: | The news of the mobilisation of Kirenian troops to put down the revolution led to the National Diet to petition Estmere and Cislania to send troops to defend against Kirenian forces. Cislanian King Karl Rudolf dithered and deferred to Estmerish Prime Minister the Marquess Moreland. Moreland indicated in the Estmerish Chamber of the Commons on the 8 June that Estmerish forces would defend liberty "''if the call comes''" but deplored the idea of another war in northern Euclea. | ||

[[File:RB-Hinrichtung.jpeg|thumb|The execution of Septemberist leader Marius Wächter.|300px]] | |||

In response to the Estmerish Kask-Jakobson threatened that any action to support the revolutionaries would constitute an attack on Kirenian interests and that Kirenian forces would not hesitate to "''bring order to northern Euclea''". Kask-Jakobson did not have the authorisation of either Juhan V nor the Kirenian army to make such pronouncements but his bluff worked; on the 13 June Moreland stated that Estmere would not support the revolutionaries. | |||

The Kirenian army meanwhile with the support of loyalist forces from the Weranian states made fast progress in defeating revolutionary forces. The revolutionary militias were unorganised and in contrast to 1786 were not mass forces whilst the support for the revolutionaries more narrow. The army crushed revolutionary forces in Roetenberg and Elbenweis after two months and in Wolfsfled after three, with Westbrücken finally surrendering to Kirenian forces on the 18 September 1828. | |||

The former revolutionary states were placed under martial law with Kask-Jakobson having unofficial control over their affairs. Revolutionary leaders were arrested with many exiled or imprisoned - the most high profile such as Wolfram Schlüter were executed. The constitutions that the revolutionaries had promulgated in March were repealed. Although the restored monarchies promised to uphold a more {{Wp|enlightened absolutist}} framework in reality they regressed into the police states of the post-1801 order albeit with repression now even more draconian. Westbrücken, which had been the centre of pan-Weranicism and revolutionary politics was placed under permanent military occupation by Roetenberg with a military governor running the city in lieu of its own government. For all intents and purposes the revolution had been completely crushed. | |||

===Aftermath=== | ===Aftermath=== | ||

The failure of the 1828 revolution was a major setback for the unification movement but did lead to nationalists and revolutionaries to learn important lessons that would serve them well in the future. Unification through a revolutionary uprising as had occurred in 1785 was a dead-end as it would be met by overwhelming Kirenian military force applied in a punitive manner, as had occurred in 1821 and 1828. The neo-Rudolphinists were entirely discredited as it became clear that Kirenia was intractably opposed to Weranian unification particularly as long as Juhan V gave a free hand to hardliners such as Kask-Jakobson to direct Weranian policy. The staunch opposition from Kirenia to any form of unification as such settled the Weranic question decisively in favour of a ''kleinostischland'' rather then ''großostischland''. Conversely Estmere who had been a traditional opponent of unification and the revolutionaries emerged as a potential ally, albeit a reluctant one that would have to actively courted by the nationalists. | |||

The most important lesson learnt from the 1828 revolution was that republicanism was not sufficiently powerful to overcome the military might of Kirenia and that an alliance with liberal monarchies coupled with a standing army that could compete with Kirenia would be key to realising unification. In practice this meant persuading the Cislanian King Karl Rudolf to support the Weranic cause - Cislania's liberal direction alongside Karl Rudolf's sympathetic view to the revolutionaries during 1828 meant that he was seen as most likely to lend support to leading unification. The fact Cislania was the strongest of the Weranic states alongside its alliance to Estmere meant it also had the most chance of militarily facing Kirenia although this would still be a daunting prospect. | |||

However this abandonment of the republican cause and the failure of the 1828 revolution would fundamentally turn the unification movement to be far more conservative then it had been in the pre-1828 paradigm. The liberal bourgeoisie would have to compromise with the entrenched aristocracy and monarchy to realise a Weranian nation-state that would in turn place a unified Werania as a far more illiberal, less positivist state then envisioned by previous unification movements. | |||

==Path to unification== | ==Path to unification== | ||

=== | ===Rise of Cislania=== | ||

===Septemberist | Although the 1828 revolution failed to gain traction in Cislania itself, during 1828 there was disquiet with the administration of moderate conservative Carsten zu Gottschall. During the zenith of the revolution in April 1828 King Karl Rudolf dismissed zu Gottschall as Minister-President instead appointing [[Ulrich von Bayrhoffer]] in his place. Von Bayrhoffer was a liberal who had connections with the revolutionary movement but was also a skilled diplomat who focused on increasing the clout of Cislania in Weranic affairs. During the revolution however Karl Rudolf took the reigns of government resulting in an excessively cautious approach to the revolution. | ||

===Cislanian-Solstianan | {{multiple image | ||

| align = left | |||

| total_width = 375 | |||

| image1 = Von bayrhoffer.png | |||

| width1 = 100 | |||

| image3 = Nikolaus Lenau 1847.jpg | |||

| width3 = 75 | |||

| footer = Cislanian Minister-President [[Ulrich von Bayrhoffer]] (left) represented the more moderate tendency of the pan-Weranicist movement whilst [[Klemens Müller]] (right) became the spokesman for its radical faction. | |||

}} | |||

Although von Bayrhoffer had connections to revolutionary movement he was mostly perceived as a wily pragmatist. Von Bayrhoffer promoted a unified Werania led by the Cislanian state but recognised that in the post-1828 context that the unification would be dependent on Cislania's ability to posture itself as a crucial part in the {{wp|balance of power}} of northern Euclea. As such von Bayrhoffer supported vigorous economic modernisation and {{wp|industrialisation}} whilst giving wholehearted support for Karl Rudolf's ongoing process of administrative rationalisation. Cislania as such acquired the nickname of the "bourgeois kingdom" as the middle class dramatically expanded as a result of the reforms pursued with the {{wp|industrial revolution}} in Werania first arriving in Cislania. | |||

Von Bayrhoffer also focused on securing Estmerish approval for Weranian unification to transcend party lines. Sympathy for the Weranian cause was much stronger amongst the more liberal [[Constitutionalists (Estmere)|Constitutionalists]] then the more reactionary [[Traditionalists (Estmere)|Traditionalists]]. Following the 1831 election the Constitutionalists lost power to the Traditionalists under [[Cecile Filmore-Richards|Cecile Filmore-Richards, the Count Warrington]]. Von Bayrhoffer was determined to secure Traditionalist support for Cislania. To do this von Bayrhoffer exploited mutual tensions between Estmere and Gaullica in Coius to secure Estmere's favour proclaiming Cislania stood in "''full support''" for Estmerish aims over disputes in northern [[Bahia]]. Von Bayrhoffer also supported Estmere's claims in eastern Kirenia to pivot Estmere to support Cislania as a check on the other. These efforts were successful albeit came with the cost of Gaullica souring on the prospect of a united Werania and more trenchantly formulating an alliance with Kirenia. | |||

In order to drum up their support for their modernising agenda Karl Rudolf and von Bayrhoffer encouraged their supporters in the Landtag to form their own political faction who would become known as the Pan-Weranic Party (''Allostischer Partei''). The pan-Weranicists sat in the middle of the Cislanian political spectrum being opposed by the anti-unification conservatives on the right and the pro-republican Septemberists on the left. Although the pan-Weranicists relied on the conservatives to continue to publish {{wp|treatise}}s supporting monarchism they entered a pragmatic alliance with the Septemberists with the common goal of furthering Weranian unification. The Cislanian Septemberists became marked by their pragmatism and willingness to work with the establishment relative to other Septemberist cells in Werania, although the relationship between von Bayrhoffer and the Septemberists particularly the influential polemicist Klemens Müller could be strained at times due to von Bayrhoffer's perceived caution and conservatism. The period between 1828 to the next breakthrough in Weranian nationalism in 1836 saw on the one hand the moderate Weranian nationalists focusing on bolstering Cislania's position as the most powerful of the Weranian states whilst on the other hand radicals such as Müller sought to rebuild the Septemberist revolutionary cells that had been dismantled by the Kirenians in 1828. | |||

[[File:Radetzky-von-radetz.jpg|thumb|{{wp|Generalfeldmarschall}} [[Karl von Littitz]] was responsible for modernising the Cislanian army.|250px]] | |||

The political reforms being spearheaded by Karl Rudolf and von Bayrhoffer coincided with a shift in the Cislanian army towards a more modernised, innovative force. Cislania had been one of the earlier adopters of the concept of a general staff which had been implemented under the Weranian Republic and whom Cislania had continued in order to replicate the success of the republican army. The teaching of war strategy in Werania largely emphasised a "''scientific approach''" as had been expounded by the former republican government. | |||

In 1834 a new Chief of Army Staff was appointed, [[Karl von Littitz]], after heavy lobbying from von Bayrhoffer. Von Littiz had long been sympathetic to the Weranian nationalist cause and attempted to position Cislania as the pre-eminent military power in northern Euclea. Unlike the scientific approach taken by his predecessors which emphasised precise planning von Littitz supported the idea of ''{{wp|Mission-type tactics|auftragstaktik}}'', which stressed objectives of military operations and the timeframe for their implementation but allowed deviation from local officers from the strict application of the plan as long as they met the overall strategic objective. This was considered to be a radical innovation within the Cislanian army and would enable Cislania to retain a strategic edge over its rivals in the development of military strategy. | |||

Karl Rudolf also had heavily pushed for a modernisation of the armed forces and their restructuring which was heavily supported by von Littitz. This modernised including an expansion of universal {{Wp|conscription}} for men to two years and to reduce the offensive capabilities of the reserve force (the {{Wp|landwehr}}) to make them a purely defensive force whilst retaining the regular army as a premier offensive force. Parliamentary control over military spending was also reduced although never entirely ceded as von Littitz had recommended. These military reforms were incredibly contentious with conservatives who supported the old, aristocratic-focused army and radicals who demanded a dominant role of the landwehr and other citizen-militia's over professional soldiers united in their opposition; however the strong alliance between Karl Rudolf, von Bayrhoffer and von Littitz enabled their implementation and ultimate vindication. | |||

===Septemberist Revolt and Solstianan War=== | |||

{{main|Bonnlitzer War}} | |||

Unlike the other Weranian states, the Grand Duchy of Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken had largely been spared the intense nationalism that had arisen in the 1820's. This was partly due to Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken in contrast to the other Weranian states being largely Amendist, particularly its historical centre Bonnlitz, rather then Catholic which encouraged a sense of Bonnlitzer exceptionalism based on its Amendist status. The personal union with [[Solstiania]] also was seen as a point of pride for the Sondermont dynasty that ruled the Grand Duchy leading to a general emphasis on a multicultural approach rather then nationalism. The Solstianian monarchs governed Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken as centralised, authoritarian state that nevertheless did not rely on censorship nor a police state like the other Weranic states. This allowed Bard I some flexibility in regards to the events of 1821 and 1828 which saw Olav II and Olaug I navigate republican sentiment by pragmatically adopting fiscal and governmental reforms whilst maintaining their political power. | |||

Despite this Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken remained one of the least industrialised of the Weranic states. The commercial elite of the personal union preferred to funnel capital into Solstiana rather then Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken which led to the state to be passed over in these decisions. This made Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken comparatively underdeveloped and heightened discontent with the middle classes, who resented their less prominent position in commercial and political life relative to Cislania to the south. | |||

In order to dislodge the monarchy the Septemberists under the leadership of Sebastian Mertz had been assembly a volunteer army that sought to "''defend the interests of the people''". Due to the relatively less repressive atmosphere in Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken relative to the other Weranian states in the post-1828 context this volunteer army saw ample recruitment in Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken which helped conflate opposition to the monarchy with Weranian nationalism. | |||

By 1836 the new Solstianan King, Bard I, became highly unpopular in Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken after passing a serires of tariffs that were seen to favour Solstiana over Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken. In May 1836 riots in the capital of Gothberg was forcibly repressed by the National Guard; this led to an upsurge in revolutionary action across the country as large peasant uprisings emerged. | |||

[[File:Guillaume Henri Dufour (Irminger).png|Sebastian Mertz led the Volunteer Army that displaced the Bonnlitzer monarchy.|250px|thumb|left]] | |||

These revolutionary movements were not nationalist or republican; by and large they demanded the dismissal of corrupt ministers, the end of the tariffs and measures to be put into place that would improve the lives of the people. However they were quickly seized upon by the Weranian nationalist movement; in a speech to the Cislanian Landtag Klemens Müller applauded the actions of the "''gallant Bonnlitzers facing the forces of tyranny''". There was also evidence that the Septemberists had planned the revolt in advance; it would later transpire that some of the rioters were paid for their actions. | |||

Sebastian Mertz, a Kirenian exile that had become part of the revolutionary movement had gathered a volunteer army of 5,000 men with the intention of overthrowing the Solstianan holdings in Werania. Mertz was a republican and high-profile Septemberist leader who had carved a reputation for himself as a charismatic adventurer who was in the informal employ of the Cislanian monarchy. Mertz approached Karl Rudolf and von Bayrhoffer with permission to use Cislanian railways to cross via Wolfsfled into Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken with his army to attempt an invasion of the territory as it was mired in revolution. Both the king and Minister-President were hesitant - the Bonnlitzer army at the time stood at 50,000 men and was commaned by Solstianan officers, who were seen as being more then capable of defeating Mertz's army. Nevertheless the two gave Mertz the go-ahead on the condition that his Volunteer Army give the appearance of approaching the expedition as if in defiance of the Cislanian crown, so to not spark a punitive reaction from Cislania's neighbours or Kirenia. | |||

The Volunteer Army arrived in Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken on the 2 June 1836. Frederick IX immediately organised a 12,000 strong detachment of the Bonnlitzer army under the command of Matthäus zu Thierse to face the Volunteer Army in the town of Brunnmund near the Wolfsfledan border. The Volunteer Army was bolstered by existing rebel forces and had high morale whilst the Bonnlitzer army was poorly led and subject to frequent desertions. To the shock of many the Volunteer Army defeated the Bonnlitzr force at the Battle of Brunnmund swelling its size to 10,000 men as Bonnlitzer army defectors and revolutionaries joined the army. This further increased to 12,000 as they took the city of Geldfurt on the 17 June. | |||

As a result of the Volunteer Army's advances Bard I order a more decisive strategy for Bonnlitzer forces at the next major engagement. Assembling an impressive force of 30,000 men Bard I directed Bonnlitzer general Pål Odegaard to order the army to undertake a stand at the fortress town of Bohenme against the Volunteer Army, who aggressively recruited revolutionaries to increase their number to an impressive 22,000 men. Unlike the Bonnlitzer army however only the defectors from the Bonnlitzer army plus the original volunteers from Cislania could be called professional soldiers, with the rest being poorly trained revolutionary militia's. As such Mertz had to be extremely careful in his application of forces during the battle. | |||

[[File:Dybbol Skanse.jpg|thumb|The Volunteer Army during the Battle of Bohenme.|350px]] | |||

Mertz however had an unexpected boon when a major revolt occurred in both Kottenwice and Gothberg, whose garrisons numbered 3,000 and 5,000 respectively. Frederick IX was forced to send 10,000 of his 30,000 men to bolster these positions leading to Mertz to commerce the attack on Bohenme. A revolt within the city by its population soon confounded the general Pål Odegaard and faced with the overwhelming force of the Volunteer Army fled the city on the 3 August to Gothberg. Odegaard's intention was to muster his 18,000 remaining troops to rout the rebels but his flight from Bohenme discredited the Solstiana in the eyes of the population; the armies in Kottenwice, Bohenme and Gothberg all surrendered to revolutionary forces. Odegaard himself was denied access to Gothberg being forced into exile by a provisional government set up in the city. | |||

With Odegaard and the Solstianans ousted on the 7 August Mertz entered Gothberg to cheering crowds. A regency was declared with a revolutionary government headed by Mertz taking power and elections scheduled for September. Many in Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken expected the creation of a constitutional monarchy rather then unification into a Weranian state despite the prevalence of Septemberists in government. A series of liberal decrees were passed including the separation of church and state, land reform that significantly expanded the power of the peasantry, the end of food tariffs and the merging of the revolutionary armies with the remnants of the Bonnlitzer army. | |||

The revolutionary action had been relatively contained up until this point due to the belief that the Solstianan armies would defeat the rebels. The new reality spurred Kask-Jakobson to lobby Juhan V to invade Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken and restore the Solstianans to power. Juhan V however vetoed this idea on the basis that Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken was not in the Kirenian sphere of influence. A declaration by the provisional government that it would restore some form of monarchy in Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken rather then a republic also sapped support from Kirenia and other Weranic states to take punitive action against Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken. | |||

Despite this pan-Weranic fervour grew during the existence of the provisional government. In September Klemens Müller arrived in Gothberg where he passionately called for the immediate unification of Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken and Cislania and the adoption of a revolutionary constitution. When the elections came on the 8 September 1836 Septemberist and pan-Weranic deputies secured an overwhelming majority. Mertz as head of the government offered Karl Rudolf the position of Grand Duke of Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken, effectively creating a {{wp|personal union}} between Cislania and Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken. Karl Rudolf pressured by the Cislanian Landtag and popular demand accepted the crown on the 17 September 1836. | |||

The acceptance of the Bonnlitzer crown was loudly protested by Solstiana, with Bard I stating that the move alongside the insurrection generally constituted a destruction of the Harimisaareke system. Bard I subsequently declared war on Cislania on the 19 September 1836 for its confirmation of the personal union with the stated purpose being to reverse the Septemberist revolt and restore the personal union. Solstiana had scant land forces but maintained a large navy; Cislania meanwhile had the reverse, with its small navy being comparably impotent. | |||

The Cislanian government whilst not expecting that Solstiana would alone be able to retake Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken did believe that a lack of external support for Cislania would enable outside powers - notably Kirenia - to agree with the Solstianan government and attempt to reimpose Solstianan authority or at least reverse the personal union with Cislania in regards to Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken. As a result shortly after the war was declared von Bayrhoffer lobbied for Estmere to recognise the personal union and assist Cislania against Solstiana. | |||

[[File:Copenhagen, the night between 4 and 5 September 1807 seen from Christianshavn.jpg|thumb|left|The Estmerish bombardment of Kvitastrott.|300px]] | |||

Though the Estmerish Prime Minister, [[Arthur Wood, Marquess Hillingdon|Marquess Hillingdon]], was privately in favour of intervening on behalf of the Cislanians, he was prevented from publicly advocating for this. King [[James III of Estmere|James III]] was concerned that any aggressive action would lead to a Kirenian intervention, and had personal qualms with an intervention due to his family ties with Bard I. At the same time, Parliament was dominated by conservative [[Viridians (Estmere)|Viridians]] who remained wary of the liberalism associated with the failed Septemberist Revolt, and worried that any Weranian unification would be a threat to their landed interests. These views changed when Solstiana allegedly fired on an Estmerish vessel, mistaking it for a Cislanian one, which outraged the King and rallied Parliament. This led to the King and Parliament supporting a declaration of war on Solstiana on the 5 October 1836. Solstiana denied it had fired upon the vessel and accused the Cislanian and Estmerish governments of a {{wp|false flag}} attack. This was suspected for some time, and it was confirmed in later document releases that the incident had been arranged by von Bayrhoffer and Marquess Hillingdon to force the King and Parliament to support Estmere's entry into the war. | |||

Estmerish intervention made the naval war far more dramatic as Estmere sent its northern fleet to engage with Solstiana's, backed in a supporting role by Cislania's fleet. The Solstianan fleet was decisively defeated in the Battle of Perovo Sea, with two-thirds of the fleet being destroyed and rest docking in Kvitastrott. Estmere to force a surrender from Solstiana performed a bombardment of Kvitastrott on the 29 October 1836 - although they were targeting the docked fleet a large amount of civilians were killed in the bombardment, putting huge pressure on Bard I to surrender. Subsequently on the 3rd November the Solstianan government announced it would cease hostilities with Cislania and Estmere by recognising the personal union between Cislania and Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken with the house of Sondermont dropping claims to the kingdom. | |||

The war shifted the balance in the Weranian states. It had showed the power of popular nationalism with the fast collapse of Solstianan authority in Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken from the Septemberist invasion as well as the weakness of monarchist support. The personal union with Cislania however indicated the growing cooperation between the Cislanian crown and Weranian nationalists who were increasingly distancing themselves from republicanism. Nevertheless the success of the Septemberists entrenched the view of radicals such as Mertz and Müller of the essential revolutionary nature of the Weranian cause, a fact that worried the reactionary governments across much of the other Weranic states. The defeat of Solstiana also removed its influence from the region whilst Estmere's increased, with Estmere now being seen as the key great power favouring the Weranian cause. Cislania was seen most to benefit however with both Karl Rudolf and von Bayrhoffer accruing substantial legitimacy both abroad and amongst Weranian nationalists. | |||

===Weranian War for Unification=== | ===Weranian War for Unification=== | ||

The personal union between Cislania and Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken whilst being seen as a boon for the nationalist cause was still perceived primarily as an expression of power for Cislania, whose commitment to the nationalist cause was still disputed. Both Karl Rudolf and von Bayrhoffer remained deliberately ambiguous as to whether they supported the cause of Weranian unification lest they incur the opposition of Kirenia. Although earlier historical accounts of Weranian unification such as [[Greger Lange]]'s ''Von Bayrhoffer in Werania'' indicated that Weranian unification was always the end goal of von Bayrhoffer more modern accounts stress that both Karl Rudolf and von Bayrhoffer were opportunist in their aims albeit saw the domination of the Weranian states by the House of Schwarzollen-Brücken as the guiding principle in Cislania's foreign affairs at the expense of Kirenia. | |||

[[File:Kronprinz Maximilian von Bayern.jpg|thumb|King [[Wilhelm IX of Roetenberg]] was a firm opponent of Cislanian expansionism and so pushed to escalate the succession crisis in Prizen to limit Cislanian power.|250px]] | |||

The alliance between the Cislanians and revolutionaries frayed significantly from 1836 to 1840 as von Bayrhoffer was seen to exclude the revolutionary nationalists from power. Metz was forced to flee in March 1837 to Estmere after being accused of attempting to formant revolution in Cislania whilst at the 1838 elections the radicals saw their influence in the Cislanian Landtag dissipate with Müller losing his seat albeit retaining one in Bonnlitz-Ostbrücken. The radical newspaper ''Der Herold'' stated in 1838 that "''content with their sphere in influence in Bonnlitz and their representation in the landtag the Cislanian bourgeoise have abandoned the nationalist and republican cause and doomed Werania to live under the boot of reaction''". | |||

The nevertheless von Bayrhoffer remained intent on expanding Cislania's power but lacked a firm pretext to do so. Von Bayrhoffer as such turned his attention to the Grand Duchy of Prizen whom he saw as particularly susceptible to an internal crisis. The Grand Duke Frederick III was severely ill and had no successor to his throne; he only possessed two daughters and Prizen's {{wp|salic law|succession law}} forbid female succession. Von Bayrhoffer therefore lobbied Prizen's Landtag to grant the Cislanian Crown Prince, [[Adalbert of Werania|Adalbert]], the throne of Prizen upon the death or abdication of Frederick III. This was heavily opposed by a coalition of Weranian states led by [[Wilhelm IX of Roetenberg]]. Wilhelm IX saw the expansion of Cislanian power with alarm given that Roetenberg was the second strongest of the Weranic states and saw any further increase in Cislania's power as weakening Roetenberg. In this Wilhelm IX had a strong ally in the form of Kirenia who saw the expansion of Cislanian power as threatening their sphere of influence in Werania, with Kask-Jakobson indicating to Wilhelm IX that Kirenia would respond with force in support of Roetenberg if the Cislanians attempted to change the status quo. Frederick III in order to defuse tensions surrounding his succession was deliberately ambiguous on its development; he claimed that he had named a list of three successors in an enclosed letter that would be opened upon his death with the Landtag given responsibility for choosing his successor amongst them. This helped temper tensions between Cislania and Roetenberg. Nevertheless Kask-Jakobson had taken the initiative to shore up support for preventing Cislanian succession forcng an agreement between the monarchs of Roetenberg, Elbenweis and Wittislich to jointly support the candidature of a non-Cislanian prince in the event of Frederick III's death. | |||