Pulacan: Difference between revisions

m (→Religion) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

|religion = {{Collapsible list | |religion = {{Collapsible list | ||

|titlestyle = background:transparent;text-align:left;font-weight:normal;font-size:100%; | |titlestyle = background:transparent;text-align:left;font-weight:normal;font-size:100%; | ||

|title = | |title = | 65% [[Tlecoyanism|Tlaloc Ixtleconism]] | 16% [[N'nhivara]] | 8% [[White Path]] | 5% {{wp|Bantu mythology|Folk religion}} | 6% [[Pulacan#Religion|Other]] }} | ||

|religion_year = 2020 | |religion_year = 2020 | ||

|religion_ref = <!--(for any ref/s to associate with religion data)--> | |religion_ref = <!--(for any ref/s to associate with religion data)--> | ||

| Line 248: | Line 248: | ||

| value4 = 5 | | value4 = 5 | ||

| color4 = gold | | color4 = gold | ||

| | | label5 = Other | ||

| | | value5 = 6 | ||

| | | color5 = grey | ||

}} | }} | ||

Revision as of 07:02, 4 May 2022

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Republic of Pulacan | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Pula e ne (Setswana) We will be blessed with rain | |

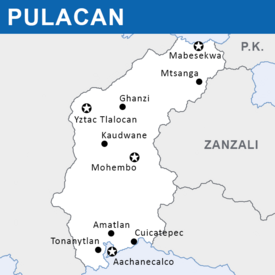

Map of Pulacan's major cities | |

| Capital | Tepetenxipaltlan (executive) Mabesekwa (legislative) Mohembo (judicial) Yztac Tlalocan (administrative) |

| Largest city | Tepetenxipaltlan |

| Official languages | Setswana, Pulatec Nahuatl |

| Recognised national languages | xKhasi languages, Raji |

| Religion (2020) | List

|

| Demonym(s) | Pulatec, Pulatl |

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic with an executive presidency |

• President | Coyotl Gontebanye |

• Chief Minister | Moctezuma Tshireletso |

• Chief of the Ntlo ya Dikgosi | Kȍhà ǂToma |

• Chief Surveyor | Tlaloc Xochiquetzal |

| Legislature | Pulatec United Legislative Assembly |

| House of Survey | |

| Ntlo ya Dikgosi House of Delegates | |

| Establishment | |

• First cave paintings | c. 73,000 BCE |

• Arrival of Bantu tribes | c. 600 CE |

• Arrival of first Nahua peoples | c. 1150 CE |

• Itzcoatl's conquest | 1476 CE |

• Return to Zacapine control | 1544 CE |

| Area | |

• | 749,856 km2 (289,521 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 46,442,816 |

• Density | 61.93/km2 (160.4/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $714,373,343,528 |

• Per capita | $21,468.51 |

| Currency | Pulatec Pula (PLP) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (Central Malaio Time) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (CE) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +254 |

| Internet TLD | .pl |

Pulacan, officially the Republic of Pulacan (Setswana: ꦫꦶꦥꦲꦄꦧꦺꦴꦭꦶꦏꦶ ꦪꦄ ꦧꦺꦴꦥꦸꦭꦄꦕꦄꦤ, Riphaboliki ya Bopulacan, Nahuatl: Tlacatlahtohcayotl Pulacan), is a sovereign country in eastern Malaio. It straddles the continent between the Vespanian Ocean on its south and the Ozeros Sea on its north, and borders Zanzali in the east and Pulau Keramat in the northeast. The current population of 46,442,816 people is spread across 749,856 square kilometers, making the nation one of the most population-dense on the continent at just over 61 people per square kilometer. The arid plains in the south of the nation are divided from the fertile forests and coastal savannahs of the north by a large section of mountains and the Djebe highlands that dominate the country. For centuries, political power has been concentrated in these highlands, lording over the two coasts. The distribution of ethnic groups in Pulacan is heavily influenced by this geography; Nahuatl peoples, the former elites in Zacapine colonial times, reside mainly on the southern coasts, while large populations of Wampar and other related groups dominate the north. Tswana and mixed Tswana-Nahuatl peoples are by far the most populous groups in the nation, with populations spread throughout, but mostly concentrated in the center of Pulacan. Small populations of mostly-nomadic xKhasi peoples exist in protected areas in the hinterlands of the country.

The xKhasi peoples were the first to arrive in what is now Pulacan, living in hunter-gatherer societies for thousands of years before their way of life was hampered by the arrival of more sedentary Komontu peoples in the 7th century CE. These peoples became the Tswana, forming various tribal nations throughout the region, concentrated in the Djebe. Contact with traders from Zacapican was established by the mid-12th century, with coastal settlements beginning at the same time. These settlements later lost connection with their homeland, and were gradually assimilated into the local Tswana population. A second wave of Nahuatl settlement occurred following the arrival of Itzcoatl, a Zacapine general sent to reestablish relations with the local population. Itzcoatl later went far beyond his mandate and swiftly conquered much of modern-day Pulacan in the name of the homeland. Following Itzcoatl's death, Nahua settlements retreated to the south coast; the north was eventually folded into Mutulese control and the central chiefdoms became tributary states of the Zacapines.

In the modern day, Pulacan employs a dual-government system that continues to balance the interests of the dueling sides in the Pulatec Civil War. United at the top by the Presidency and the Pulatec United Legislative Assembly (PULA), the republican government and the government representing the Tswana chiefdoms and monarchies operate largely autonomously, though the united nature of the PULA allows for dual cooperation on major issues. As such, Pulacan is one of the few states in the world with a tricameral parliament, featuring two co-equal lower houses and an upper house. Internationally, Pulacan is a member of the Forum of Nations and the Association of Malaio-Ozeros Nations, and its government operates as a full member of the Vespanian Exchange Institute.

Etymology

The name Pulacan derives from two separate languages, and reflects the multicultural origins of the country. The word "pula" is a word in Tswana, literally referring to "rain"; the word carries deep positive significance for many Setswana speakers, as it stands for the coming of the Tswana peoples from an arid homeland to their current center of population in the often humid and rainy highlands. The suffix -can is Nahuatl in origin, and is used to denote a location, like the suffix -ia in Hellenic. Originally a name applied by Zacapine settlers on the coast to the mountainous highlands of the country on their first arrival, the name eventually became metonymous, and later synonymous, with the polity as a whole, reflecting the eventual takeover of modern-day Pulacan by the collection of highland Tswana chiefs.

History

The first settled peoples arrived in what is now Pulacan via the northern plains in 35,000 BCE.

Komontu Arrival

The arrival of the ancestors of the Tswana peoples in Pulacan is impossible to date precisely. The scholarly consensus supports the idea that the groups split off from the larger Komontu migration in the 500s CE, spending the next two centuries settling the northern coastal plains and the Djebe highlands. The 800s would see the beginnings of the modern tribal system, as well as the first consistent evidence of Tswana settlement that remain extant today. Some tribes made their way to the southern coasts; their settlements failed to achieve the same level of growth as those in the central highlands. It is currently believed that these settlements, thanks to their isolation from the larger trade nodes of the Karaihe and Ozerosi regions, could not generate trade volume beyond foodstuffs like grains and fish, and thus became subservient to the mountain chiefdoms. These tribal nations were able to generate significant power and prestige through governing the trade between the southern settlements and the Karaihe, which shifted political power to the highlands and allowed for the construction of major settlements like Kaudwane, the oldest continually-inhabited city in Pulacan. The increasing disparity between the southern coasts and central Djebe tribes created mutual animosity despite their mutual trade links, and the two drifted further apart culturally over the ensuing three centuries.

The north of modern-day Pulacan was increasingly subsumed over the 10th century by the Tahamaja Empire. Though Komontu settlements persisted under their rule, many either relocated to modern-day Zanzali and formed part of the WaMzanzi group or were partially assimilated into the greater Tahamaja community. The Tahamaja constructed a pelabuhan as the center of their government and trade activities on the region, which later became the commercial center of the modern-day city of Mabesekwa. Direct Tahamajan control never extended far inland from this center, but it nonetheless served as a way to project indirect influence into the hinterlands. The pre-eminent authority at Mabesekwa was the panguwasa, who served both as harbor-master for the pelabuhan and as the de facto ambassador of Tahamajan control. This position was given to sufficiently pliable and talented local leadership as a go-between with local populations, and often served as a means for introducing cultural knowledge to their native populations. This assimilation saw the partial introduction of the N'nhivara religion to the area, partially supplanting and then syncretizing with local beliefs. More importantly, this period saw the introduction of the first writing system in modern-day Pulacan, the Uthire script. This script's use in Pulacan co-evolved to resemble the modern-day Mataram script, currently in use in parts of Pulau Keramat. The script is used today to write words in Setswana, and though the characters are the same, the contents of Mataram and Setswana writings are not mutually legible. The Uthire script spread in popularity along the existing trade routes to the Djebe highlands, where many tribes further cemented their power by employing dedicated scribes to recording their achievements and keeping bureaucratic records. State records begin to exist around 1050 CE, with the first coded laws appearing shortly after. From these records, a pattern emerges of tribal nations evolving from chiefdoms into more complicated states with various permanent (or semi-permanent) capitals, bureaucracies, laws and succession systems. Numerous wars of conquest were undertaken during this time, as well, with a complex network of vassal states, subjugated territories, and alliances all inhibiting one single group from rising to regionwide hegemony. These statelets would continue to evolve on this path for the next century, in sharp contrast with the southern coastal plains groups, which saw little societal change or population growth. The relative weakness of these southern tribes proved advantageous for the Zacapines and their merchant fleets, who began settling the area via trading and resupply posts starting in the 12th century.

Zacapine Settlement and Itzcoatl

Nahua peoples from Zacapican first arrived around 1150 CE, with word reaching Djebe-based chroniclers around 5 years later. The original purpose of such settlement was to augment the Zacapine thalassocracy; the plains provided easy access to hardwood for repairing ships and the locals could be traded with for supplies. Due to the nature of these early settlements, the first century of Nahua presence was extremely limited, with traders largely sticking to the coast, barring a few notable commercial expeditions into the highlands. After around a century, however, Ixtleconist priestly societies in Zacapican began organizing missionary expeditions, seeing the populated regions as a perfect place to begin spreading their faith. Many missionaries found difficulty in spreading the faith until the Ixtleconist minor rain deity of Tlaloc was used as a way to syncretize local reverence for rain and water into the religion. With the implication that Tswana folk religious beliefs were correct and merely part of a wider system of worship, missionaries began seeing wild success. Some highland kings were early adopters of the religion; many saw it as a way to increase trade and friendly relations with a powerful foreign nation as a way to back themselves against potential Tahamaja aggression, while others saw a unitary religion with a defined priesthood as an effective tool of state that could help them more effectively dictate the lives of their subjects. Whatever their reasons, large swathes of Pulacan outside of Tahamaja control had converted to the so-called "Tlaloc Sect" of Ixtleconism by the time of Mount Siriwang's eruption.

The eruption of Mount Siriwang in 1353 greatly disrupted the world's mercantile enterprises, with the Zacapines especially suffering a near-total loss of their trade connections. As a result, the communities of Nahua peoples were completely isolated from the mother country. With the occasional exception of the priestly class, these groups began intermingling with the local Tswana groups out of necessity, as economic support from home was no longer available. The result was the first documented population in Pulacan of coyotec, or mixed peoples, before most of these were gradually being subsumed into the wider Tswana community. Only small pockets of coyotec peoples remained in what one chronicler described as "husks of the coastal settlements that bore the ruinous marks of once standing much larger" by the time of Itzcoatl's arrival. The loss of trade saw a severe economic downturn in the south, while the highlands suffered from a lack of trade with the Tahamaja. The eruption impacted the north of Pulacan much more severely than in the south or the highlands, as the area saw direct, large-scale climate disaster and the collapse of their former Tahamajan overlords. Such catastrophes depopulated the region significantly. An area that once had a near-equivalent population to the Djebe highlands now possessed only a fraction thanks to the series of calamities that decimated the local population. The next few decades were, until recently, referred to as the "Pulatec Dark Age" by historiographers thanks to the volcanic winter and general decline of learning, arts, economy, and standard of living.

Road to Independence

Geography

Climate

Government

Republican Government

Large sections of the coasts of Pulacan fall under the so-called "Republican government." Within this part of the country, the populace directly elects representatives to the House of Delegates and to local administrative bodies. The region is subdivided into altepemeh (singular: altepetl), subdivisions with limited authority centered in a principal municipality. Each altepetl is, in turn, allotted electoral seats in the House of Delegates.

Tribal Government

The leadership of the so-called "tribal government" is represented by the Ntlo ya Dikgosi, or the Council of Chiefs. This body operates as both a legislative and executive body, with each member being either the executive monarch of a subnational body, or an appointed elector representing a tribe. The land area directly governed by the tribal government covers most of the interior of Pulacan, with only the extremes of the southern and northern coasts being under the direct supervision of the republican government and its House of Delegates.

Complicating the system is the presence of cities. The Pulatec Political Settlement allowed for the existence of official "free cities," granted charters by their local government, to stand directly in the Ntlo ya Dikgosi. Most cities, however, have instead opted to elect representatives to their local governments and to the House of Delegates. This leads to a complicated political situation whereby these free cities are governed both the laws of the Ntlo ya Dikgosi and their local monarchs alongside the House of Delegates' laws. These laws can sometimes be in opposition to each other. As such, some local governments opt to create exceptions for cities in drafting local laws, while other cities elect their own municipal governments that declare which laws they choose to enforce. The latter option is controversial, and usually requires a city with great political power already to successfully implement.

Subnational Monarchies

Within the dual-government system,

Military

Foreign Affairs

Education

Economy

Alanahr can do this bit idc

Transportation

Culture

Ethnic Groups

Religion

Music

Entertainment

Cuisine

Hiero time