Toubacterie: Difference between revisions

m (→Legacy) |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

[[File:Official medallion of the British Anti-Slavery Society (1795).jpg|200px|thumb|left|Logo of the Estmerish Abolitionist Coalition, who campaigned for the abolition of slavery in Bahia.]] | [[File:Official medallion of the British Anti-Slavery Society (1795).jpg|200px|thumb|left|Logo of the Estmerish Abolitionist Coalition, who campaigned for the abolition of slavery in Bahia.]] | ||

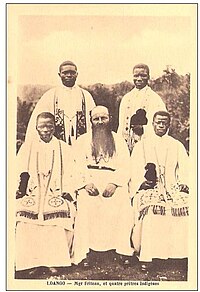

Clerical pressures were one of the major push factors on the Euclean side in the carrying out of the Fatougole. Following the abolition of {{wp|slavery}}, many priests preached the moral impermissibility of keeping slaves and saw it as the duty of the Euclean powers to rid the world of this moral evil. Despite the ban of trading slaves with Euclean powers, [[Bahian slavery|slavery]] was still a key part of the Bahian economy and played an important social and cultural role. The priests saw it as imperative that the Eucleans stop this phenomenon, and employed large public campaigns which drew upon the testimonials of freed slaves to turn the public in favour of greater involvement. These campaigns were boosted when reports came in of the atrocities suffered by the Mirites, as tales of barbaric heathens massacring their fellow Sotirians were extremely galvanising for public opinion. In 1808, prompted by these pressures, the Gaullican administration in [[ | Clerical pressures were one of the major push factors on the Euclean side in the carrying out of the Fatougole. Following the abolition of {{wp|slavery}}, many priests preached the moral impermissibility of keeping slaves and saw it as the duty of the Euclean powers to rid the world of this moral evil. Despite the ban of trading slaves with Euclean powers, [[Bahian slavery|slavery]] was still a key part of the Bahian economy and played an important social and cultural role. The priests saw it as imperative that the Eucleans stop this phenomenon, and employed large public campaigns which drew upon the testimonials of freed slaves to turn the public in favour of greater involvement. These campaigns were boosted when reports came in of the atrocities suffered by the Mirites, as tales of barbaric heathens massacring their fellow Sotirians were extremely galvanising for public opinion. In 1808, prompted by these pressures, the Gaullican administration in [[Ouagedji|Bertholdsville]] (Modern day Ouagedji) passed a law which effectively criminalised the practice of [[Bahian Fetishism]] in all areas under their control. As more and more missionaries came to Bahia, they pushed further and further inland and came into conflict with the locals. Pressured by the public, the colonial authorities guaranteed the protection of these missionaries. This caused armed conflicts, precipitating the expeditions which would bring about the Fatougole. | ||

Equally important in the expansion of Euclean involvement in Bahia were the economic concerns. For centuries, Bahia had been renowned for its vast mineral wealth and this was of interest to many {{wp|capitalists|industrialists}} who saught them for themselves. While {{wp|gold}} was the primary attraction for these men due to the fame of the vast mines of the [[Kambou Valley]] and the [[Gonda river]], there was also significant interests in the vast deposits of {{wp|copper}} and other metals which were rumoured to be present. An important economic goal was the [[Adunis to Mambiza Railway|Adunis to Sainte-Germaine Railway]], which linked [[Gaullica]]'s two most important colonial ports with the vast mineral wealth of inner Bahia. Many of these colonial expeditions were more or less {{wp|Anarcho-Capitalism|privately funded}}, with large swathes of land becoming the property of individuals. A prominent example is that of [[Charles Fitzhubert]], who led the revitalisation of [[Estmere|Estmerish]] colonisation in [[Rwizikuru|Rwiziland]] in order to gain control its rich ports, one of which still bears his name. These economic interests provided major financial boosts for the expeditions, especially when coupled with the missionary zeal of the Euclean populace. | Equally important in the expansion of Euclean involvement in Bahia were the economic concerns. For centuries, Bahia had been renowned for its vast mineral wealth and this was of interest to many {{wp|capitalists|industrialists}} who saught them for themselves. While {{wp|gold}} was the primary attraction for these men due to the fame of the vast mines of the [[Kambou Valley]] and the [[Gonda river]], there was also significant interests in the vast deposits of {{wp|copper}} and other metals which were rumoured to be present. An important economic goal was the [[Adunis to Mambiza Railway|Adunis to Sainte-Germaine Railway]], which linked [[Gaullica]]'s two most important colonial ports with the vast mineral wealth of inner Bahia. Many of these colonial expeditions were more or less {{wp|Anarcho-Capitalism|privately funded}}, with large swathes of land becoming the property of individuals. A prominent example is that of [[Charles Fitzhubert]], who led the revitalisation of [[Estmere|Estmerish]] colonisation in [[Rwizikuru|Rwiziland]] in order to gain control its rich ports, one of which still bears his name. These economic interests provided major financial boosts for the expeditions, especially when coupled with the missionary zeal of the Euclean populace. | ||

| Line 66: | Line 66: | ||

[[File:Darfur refugee camp in Chad.jpg|200px|thumb|{{wp|Refugee camp}} for [[Mirites|Mirite]] {{wp|refugees}} in southern [[Djedet]].]] | [[File:Darfur refugee camp in Chad.jpg|200px|thumb|{{wp|Refugee camp}} for [[Mirites|Mirite]] {{wp|refugees}} in southern [[Djedet]].]] | ||

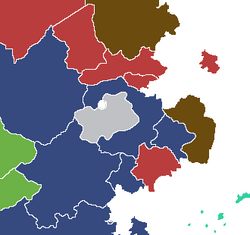

The Euclean domains in Bahia were carved out in rather arbitrary ways, often being drawn out in boardrooms back in the Euclean capitals by people who had no knowledge of the complex demographics of the lands. When information was used, it primarily relied on geographic features such as rivers and mountain ranges. This meant that Bahia was divided with little attention paid even to the existing borders of [[Hourege|Houregic states]] in the area, let alone ethnic and religious populations. The resulting holdings were therefore highly artificial constructions. In addition to this, colonial authorities often practiced {{wp|divide and rule}} tactics. By turning ethnic groups who had previously lived more or less harmoniously together and arbitrarily distributing borders, the Euclean powers ensured that following independence these states swiftly fell into civil war. The rassemblement of different ethnic groups into artificial states can be seen in conflicts such as the [[ | The Euclean domains in Bahia were carved out in rather arbitrary ways, often being drawn out in boardrooms back in the Euclean capitals by people who had no knowledge of the complex demographics of the lands. When information was used, it primarily relied on geographic features such as rivers and mountain ranges. This meant that Bahia was divided with little attention paid even to the existing borders of [[Hourege|Houregic states]] in the area, let alone ethnic and religious populations. The resulting holdings were therefore highly artificial constructions. In addition to this, colonial authorities often practiced {{wp|divide and rule}} tactics. By turning ethnic groups who had previously lived more or less harmoniously together and arbitrarily distributing borders, the Euclean powers ensured that following independence these states swiftly fell into civil war. The rassemblement of different ethnic groups into artificial states can be seen in conflicts such as the [[Mabifian-Rwizikuran War]] which was fought over the majority [[Irfan|Irfanic]] region of [[Inkiko]], the [[Garamburan War of Independence]], and the continuing [[Makanian Conflict]]. The divide and rule tactics also created conflict within states over natural resources, with the access to these being altered and granted to more loyal groups. In some cases this has even resulted in genocide, such as that of the [[Mirites]] in the [[Chirange]]. | ||

Euclean campaigns to institute {{wp|White trash|Euclean culture}} in Bahia were highly destructive for local cultures. The {{wp|caste system}} was abolished, leaving a void in many areas which was not filled. Many folk religious practices and traditional ceremonies were criminalised, leading to their abandonment. Other cultural practices were also abolished, such as those relating to {{wp|marriage}} and funerals. This led to crises of identity amongst much of the Bahian population, resulting in a phenomenon sometimes known as the {{wp|Mal du siècle|Aïibe ka Djâmanou}} within Bahian literature. The Aïibe ka Djâmanou describes the intense feeling of longing for one's own culture and insecurity which comes with the destruction of one's identity and is shown in novels such as [[My Father had Six Cows]] by [[Ibrahim Barkindo]]. This cultural malaise is often cited as a key factor in the development of the [[Djeli pop]] musical genre, which has for its goal the renaissance of traditional Bahian culture and a new confidence in Bahian identity. Cultural destruction was also perpetrated with the theft of cultural treasures from Bahia, which were then displayed in private collections and in {{wp|museums}}. The repatriation of these treasures has been a controversial political issue in recent times. | Euclean campaigns to institute {{wp|White trash|Euclean culture}} in Bahia were highly destructive for local cultures. The {{wp|caste system}} was abolished, leaving a void in many areas which was not filled. Many folk religious practices and traditional ceremonies were criminalised, leading to their abandonment. Other cultural practices were also abolished, such as those relating to {{wp|marriage}} and funerals. This led to crises of identity amongst much of the Bahian population, resulting in a phenomenon sometimes known as the {{wp|Mal du siècle|Aïibe ka Djâmanou}} within Bahian literature. The Aïibe ka Djâmanou describes the intense feeling of longing for one's own culture and insecurity which comes with the destruction of one's identity and is shown in novels such as [[My Father had Six Cows]] by [[Ibrahim Barkindo]]. This cultural malaise is often cited as a key factor in the development of the [[Djeli pop]] musical genre, which has for its goal the renaissance of traditional Bahian culture and a new confidence in Bahian identity. Cultural destruction was also perpetrated with the theft of cultural treasures from Bahia, which were then displayed in private collections and in {{wp|museums}}. The repatriation of these treasures has been a controversial political issue in recent times. | ||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

One of the most visible aftereffects of Toubacterie on Bahia is in the religious demographic changes. The colonial powers were prolific proselytizers, with {{wp|missionaries}} making up a large portion of the colonial efforts. These missionaries saw immense successes, especially in [[Bahian fetishism|Fetishist]]-majority east Bahia where fetishism was all but eliminated. These dramatic changes in the religious landscape resulted in the destruction of many traditional cultural practices which were seen as being {{wp|heresy|heretical}}, a factor which played into the Aïibe ka Djâmanou. In the modern era, [[Sotirianity]] is the largest religion in Bahia, with the states of [[Rwizikuru]] and [[Tabora]] both having almost 100% of the population following the faith and almost 90% in [[Garambura]]. [[Irfan]], once the dominant faith in Bahia, is now more or less limited to its heartland in [[Mabifia]]. The linguistic changes are equally important. Within the {{wp|Francophonie|Gaullophonie}}, roughly 50% of Bahians are able to speak the language natively and most can speak some. The language forms a key {{wp|lingua franca}} in the region, permitting communication between ethnic groups and different countries in a more neutral manner. The major outlier in this trend is [[Tabora]], where the speaking of {{wp|German language|Weranian}} was criminalised upon independence. | One of the most visible aftereffects of Toubacterie on Bahia is in the religious demographic changes. The colonial powers were prolific proselytizers, with {{wp|missionaries}} making up a large portion of the colonial efforts. These missionaries saw immense successes, especially in [[Bahian fetishism|Fetishist]]-majority east Bahia where fetishism was all but eliminated. These dramatic changes in the religious landscape resulted in the destruction of many traditional cultural practices which were seen as being {{wp|heresy|heretical}}, a factor which played into the Aïibe ka Djâmanou. In the modern era, [[Sotirianity]] is the largest religion in Bahia, with the states of [[Rwizikuru]] and [[Tabora]] both having almost 100% of the population following the faith and almost 90% in [[Garambura]]. [[Irfan]], once the dominant faith in Bahia, is now more or less limited to its heartland in [[Mabifia]]. The linguistic changes are equally important. Within the {{wp|Francophonie|Gaullophonie}}, roughly 50% of Bahians are able to speak the language natively and most can speak some. The language forms a key {{wp|lingua franca}} in the region, permitting communication between ethnic groups and different countries in a more neutral manner. The major outlier in this trend is [[Tabora]], where the speaking of {{wp|German language|Weranian}} was criminalised upon independence. | ||

Toubacterie was also responsible for the creation of a large Bahian diaspora across the world, primarily in [[Euclea]] and in their colonies in [[Asteria Inferior]] and [[Asteria Superior]]. The Asterian diaspora is primarily composed of the descendants of freed slaves who were brought from Bahia during the [[Maouhersa]], the name given by Bahians to the Bahian slave trade. The effects of this population movement can be seen in nations such as [[Imagua and the Assimas]] where the majority of the population are descended from Bahian slaves. In Euclea, the diaspora is a product of {{wp|imigration}}. Following the conflicts that marked the [[Kaoule]], many Bahians sought refuge with their former colonists, a trend which has continued following the other wars in the subcontinent's history. One of the most notable diasporic communities is that of the [[Mirites]], who faced intense persecution and even {{wp|genocide}} during the [[First Mabifian Civil War]] and again in the aftermath of the [[ | Toubacterie was also responsible for the creation of a large Bahian diaspora across the world, primarily in [[Euclea]] and in their colonies in [[Asteria Inferior]] and [[Asteria Superior]]. The Asterian diaspora is primarily composed of the descendants of freed slaves who were brought from Bahia during the [[Maouhersa]], the name given by Bahians to the Bahian slave trade. The effects of this population movement can be seen in nations such as [[Imagua and the Assimas]] where the majority of the population are descended from Bahian slaves. In Euclea, the diaspora is a product of {{wp|imigration}}. Following the conflicts that marked the [[Kaoule]], many Bahians sought refuge with their former colonists, a trend which has continued following the other wars in the subcontinent's history. One of the most notable diasporic communities is that of the [[Mirites]], who faced intense persecution and even {{wp|genocide}} during the [[First Mabifian Civil War]] and again in the aftermath of the [[Mabifian-Rwizikuran War]] and [[Second Mabifian Civil War]]. Many fled the country, and while large amounts fled to neighbouring [[Djedet]] and [[Rwizikuru]] many fled to Euclea. The suburb of [[Little Makania]] in [[Spálgleann]], [[Caldia]] is home to thousands of Mirites, with many more spread across Euclea. The Bahian diaspora in Euclea are often disadvantaged, forced to live in {{wp|quartiers populaires|lower income areas}} and face {{wp|racism}} and {{wp|discrimination}} on account of their skin colour. This is accentuated by {{wp|far-right populism}}, with groups such as the [[Tribune Movement]] in [[Etruria]] rallying against Bahian immigration. The Bahian diaspora is highly influential in the sphere of {{wp|popular culture}}, with an effect on music and fashion. A large amount of Bahians also leave for economic reasons, which has been criticised both by [[Ternca|Euclean leftists]] and [[Pan-Bahianism|Pan-Bahianist intellectuals]] as contributing to {{wp|brain drain}} and the slowed development of Bahia. | ||

[[Category:Bahia]] | [[Category:Bahia]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:46, 6 March 2022

| Part of a series on |

| Bahia |

|---|

|

| History |

| Geography |

| Politics |

| Languages |

| Notable settlements |

| Countries |

Toubacterie (lit. "rule by the white man" - of Ndjarendie origin), also referred to as Murungocracy or Murungerie in Estmerish colonies, is the name given to the period of time where white Eucleans ruled over Bahia. During Toubacterie the Euclean colonial powers rooted out or siginificantly altered the semi-feudalistic system of Hourege that had dominated Bahian civilisation for centuries prior, and was influential for the migration of people groups into Bahia such as the Yebase in Garambura and Murungu in Rwizikuru.

While the start of Toubacterie and its initial relationship with Hourege is debated, many agree that the settling of trading cities such as Sainte-Germaine and Port Graham in the 17th-century kicked off the rise of Toubacterie, which was influenced further by the Floren Empire's conquests of Tsabara during the Pereramonic Wars. Toubacterie also did not become the antithesis of Hourege, nor actively sought to remove it from Bahian society, until the scramble for Bahia began in the 19th century, and vast swathes of land were claimed or conquered for the Euclean powers.

Before Toubacterie

Precolonial Bahia was marked by the Houregic system, a semi-feudal system of administration which had dominated the region since the Bahian Consolidation. Under Hourege Bahia had entered a golden age due to trade off its precious materials, particularly gold and ivory, which were traded with the outside world. Several strong states had emerged, such as the veRwizi Empire and Kingdom of Kambou, which became centres of education and arts. The capitals of these larger Houregic states were, at their peak, able to rival the great cities of Euclea and other areas in Coius. This prosperity was only temporary, however. The upper castes grew increasingly affluent and concentrated more wealth into themselves. This was most notable among the clergy, who were not taxed under the conventional Houregic system and therefore their riches were essentially untouchable. The warrior castes as well became complacent in their wealth, preferring to use slaves in combat than risk themselves and demanding privileges from their Karanes in return for their support. This meant that the Houregic system became increasingly inefficient and became a burden on progress. Notably, the disenfranchisement of the mercantile caste effectively blocked the development of an urban middle class and caused the economies to stagnate. This corruption, in turn, led to the weakness of the education system and meant that Bahia began to trail behind the Euclean powers of the age.

Slavery had always been a part of Bahian culture, and slaves were often bought and sold as property in Bahian societies before the arrival of the Eucleans. However, the taking of slaves was a ritualised part of warfare in Bahia and as such a relatively rare occurrence, with most slaves being born into captivity. The arrival of the Euclean nations, which sought cheap labour for the cultivation of labour-intensive crops such as cotton within their Asterian colonies, created a strong market for slaves, one which the elites of the Houregic states were eager to fill. The slave trade started out slowly, but as the existing market of slaves was too small to account for the demand of the Euclean nations Karanes began to wage wars in order to take more slaves. This caused instability in Bahia, which created an opening for the Euclean nations to take a foothold in the subcontinent in order to protect these interests.

Religiously, Bahia was still highly divided. Eastern Bahia was dominated by Irfan, which had swept across the continent at the beginning of the Bahian Consolidation and continued to spread by trade and conquest. Large Orthodox Sotiran communities were also present in Djedet and northern Mabifia, with smaller communities spread across the rest of the subcontinent. Notably, there were significant numbers of Mirites dispersed in most major Houregic states. The rest of the population practiced forms of Bahian Fetishism, a traditional polytheist faith group which was not centralised and primarily revolved around the worship of individual gods using idols. The advent of Catholic missions in Bahia is highly linked with the start of Toubacterie as a historical era.

Houregic Toubacterie

At first, the goals of the Eucleans were limited to the economic sphere instead of direct control. The start of Toubacterie is generally accepted to be in 1628, with the foundation of Port Graham by Estmerish merchants in modern day Rwizikuru. This was the first permanent settlement by Eucleans in Bahia, and marked the beginnings of the shift from trade as equal partners to Euclean hegemony. This was followed by the foundation of several other settlements by other Euclean powers on the Banfuran coast of Bahia. Initially, the purpose of these settlements was for their economic benefit, as by building their own ports the Eucleans escaped the need to pay port duties to the coastal Karanes. However, these settlements also attracted Sotirian missionaries who wished to evangelise the Bahian population. Military forces were also dispatched into these settlements in order to protect them from attack from the local Karanes, who recognised that if they lost their monopoly on berthing rights they would lose a large portion of their income.

Seeing the weakness of the corrupted Houregic system, the Eucleans initially used it to their own advantage. Seeing that stable states on their borders were the easiest to deal with, puppet states were established. The Hourege of Bouïzou, a Barobyi state in Mabifia, converted to Solarian Catholicism in 1640 and chose to collaborate with the Gaullicans, leading to their domination of the area. Other local Karanes were also converted, providing the nascent Euclean presence with buffer states to protect them from the larger Ndjarendie and Rwizi states which were still able to pose a threat despite their decay. In the areas under indirect Euclean control, life more or less continued as normal. The main changes came with the suppression of the merchant caste who found themselves subjected to high taxation, sometimes having to pay duties both to their Karane and to the Eucleans. The Euclean powers ensured their dominance of the slave trade by forcing local authorities to sign decrees that only permitted the sale of slaves to Euclean merchants. The caste system itself was not touched in this period, and while Catholicism was encouraged Bahians were able to practice their own religions.

The early Toubacteric era also marks the emergence of the Yebase in Bahia, as well as the rise of the Mirites to a dominant position. The rise of Euclean involvement in Bahia necessitated a local administrative cadre and constabulary, as there were not sufficient numbers of Eucleans who migrated to the new settlements. The Mirites were seen as an ideal partner for Euclean control. They were already Sotirians, albeit of a mystical branch, and were well integrated into the local power structures. In addition, they often suffered persecution at the hands of the local populations and so had no qualms about working with the Euclean administrations. Mirite clerks and administrators would form the backbone of Toubacterie in its initial stages, and even after the development of a domestic Solarian Catholic population would remain influential. The Yebase were another Bahian Sotirian group who were employed by the Euclean powers. Meharic Sotirians, the Yebase were employed primarily in Garambura. A versatile caste, they were able to fill the roles of merchants, warriors and administrators. This flexibility, combined with their religious similarity, meant that the Yebase were an ideal tool for Euclean control.

Fatougole

The phase of indirect influence over the various Bahian polities by the Euclean powers eventually shifted to more direct control, during a period of roughly 30 years. This is known as the Fatougole, from a Ndjarendie root meaning "to shatter after falling to the ground", which encapsulates the sheer speed at which Bahia was annexed by the Euclean powers. The process saw the complete annexation of the subcontinent and the start of oppressive policies towards cultural and religious practices, with the effects of the violent repartition of lands and imposition of language, religion and culture still influential on modern Bahia. The start of the Fatougole is debated, but it is usually considered to have started in 1811 with the annexation of Ourafade which marked the start of the Kambou Expedition.

By the dawn of the 19th century the Houregic system was all but nonexistent. With the abolition of slavery in Gaullica in 1790, the two major powers in the region had banned the trade of slaves. This destroyed the economies of the Houregic states, which had shifted their focus in order to accommodate the Euclean demand for slaves to the point where this single industry accounted for the vast majority of their economic activity. When almost overnight the market was removed, the states fell into shock. Karanes were no longer able to pay their warriors, who revolted against them and installed their own leaders, and even the great Houreges had trouble maintaining their empires which began to crumble. In this chaos many areas simply reverted to the Sâretic system for stability, leading to the commonly used Euclean term to refer to the event, the "Second Consolidation". The collapse led to a breakdown in social order, with many taking their anger out against the Mirites after rumours spread that they had orchestrated the event. Mirites fled to the Euclean controlled coastal areas seeking refuge, bringing with them horror stories of massacres.

Clerical pressures were one of the major push factors on the Euclean side in the carrying out of the Fatougole. Following the abolition of slavery, many priests preached the moral impermissibility of keeping slaves and saw it as the duty of the Euclean powers to rid the world of this moral evil. Despite the ban of trading slaves with Euclean powers, slavery was still a key part of the Bahian economy and played an important social and cultural role. The priests saw it as imperative that the Eucleans stop this phenomenon, and employed large public campaigns which drew upon the testimonials of freed slaves to turn the public in favour of greater involvement. These campaigns were boosted when reports came in of the atrocities suffered by the Mirites, as tales of barbaric heathens massacring their fellow Sotirians were extremely galvanising for public opinion. In 1808, prompted by these pressures, the Gaullican administration in Bertholdsville (Modern day Ouagedji) passed a law which effectively criminalised the practice of Bahian Fetishism in all areas under their control. As more and more missionaries came to Bahia, they pushed further and further inland and came into conflict with the locals. Pressured by the public, the colonial authorities guaranteed the protection of these missionaries. This caused armed conflicts, precipitating the expeditions which would bring about the Fatougole.

Equally important in the expansion of Euclean involvement in Bahia were the economic concerns. For centuries, Bahia had been renowned for its vast mineral wealth and this was of interest to many industrialists who saught them for themselves. While gold was the primary attraction for these men due to the fame of the vast mines of the Kambou Valley and the Gonda river, there was also significant interests in the vast deposits of copper and other metals which were rumoured to be present. An important economic goal was the Adunis to Sainte-Germaine Railway, which linked Gaullica's two most important colonial ports with the vast mineral wealth of inner Bahia. Many of these colonial expeditions were more or less privately funded, with large swathes of land becoming the property of individuals. A prominent example is that of Charles Fitzhubert, who led the revitalisation of Estmerish colonisation in Rwiziland in order to gain control its rich ports, one of which still bears his name. These economic interests provided major financial boosts for the expeditions, especially when coupled with the missionary zeal of the Euclean populace.

Woundie

With Bahia subjugated politically and economically, the Eucleans began to work towards sculpting the subcontinent in their own image culturally. This often took the form of mandatory classes in Gaullican, Estmerish and Weranian, the closure of Beytols and Fetishist shrines and propagation of Solarian Catholicism, often as a direct part of the educational system, and the criminalisation of cultural practices deemed to run against Euclean moral standards. This period is known in Bahia as Woundie, from a Ndjarendie root meaning long rains as it is often seen as a time of great sadness by the Bahian people, with the wounds still being felt today.

Native languages were suppressed, in many cases even being criminalised in public life. In Mabifia, the Adlam script itself was banned from being printed and any written Ndjarendie had to use the Solarian alphabet. Such measures were seen to be effective in limiting the capabilities of the natives to organise a rebellion, as they made them less comfortable with their own languages. Euclean languages were promoted not just for this reason, but also to ensure that a common language was shared between the diverse ethnic groups to make administration easier. Euclean style education was introduced, with the goal of raising literate Bahians who would see the benefits of their new lives and spread it back to their communities.

Religious persecution was a major part of Woundie, given the vested interests of the Euclean clergy in the colonial project and the religious sympathies of many of the colonial governors. The colonial governments were especially hostile towards Bahian fetishism, which was seen as a barbaric pagan practice due to its acceptance of human and animal sacrifice. Fetishist shrines were destroyed and the idols cast out into the streets and disrespected, even urinated on, in order to prove that they held no power, and practice of any fetishist faiths were criminalised. While these tactics were brutal, prompting riots in many cities, they were highly effective. In Garambura in 1841 at the start of Euclean colonisation, the population was estimated to be 70% Fetishist. In 1849, just eight years later, this population was estimated to be 4%. Irfan was also targeted, although its status as a centralised and established faith made this task more difficult. In Kambou, the centre of Ndjarendie Irfan, over sixty Beytols were closed down by the Gaullicans while twelve churches were built.

One aspect of Bahian life which was heavily targeted was the caste system. This had been part of Bahian life since the Sâretic period and was deeply ingrained into all aspects of Bahian society. Seen as advocating slavery and impeding on the liberty of man, the caste system was officially abolished by all of the colonial powers in their territory. Anyone who was found to be keeping slaves would face strict punishments, and practices such as the ownership of a slave's children and the master's right to his slaves were abolished. In the army, native soldiers were quartered together no matter their caste background, a policy which eventually resulted in the Bahian Mutiny, and it became illegal to bar people from locations or groups on account of their caste. The efforts against the caste system saw less success than those against Fetishism, however. The practice was so ingrained into the Bahian psyche that even after several generations of Euclean-style education it was still respected, and due to the vast size of the subcontinent, there were still rural areas where the caste system continued unabated.

Decline

The decline of Toubacterie is conventionally linked with the rise of Pan-Bahianism and anti-colonialism as prominent political ideologies within Bahia. The first concerted anti-colonial uprising took place in Mabifia in 1883, when Irfanic Ndjarendie soldiers of the warrior caste were forced to lodge themselves with former slaves. Rather than accept this slight, the soldiers set fire to their barracks and fired upon their Gaullican officers. As news spread of the act, soldiers across Mabifia and even in other regions of Bahia took up arms in a revolt known as the Sougoulie. The revolt soon evolved from a complaint based on caste affiliations into an uprising against Toubacterie in general, especially the cultural suppression which took place. Lacking a central figure, the mutiny was eventually crushed by the Euclean powers who sent in troops in order to protect assets such as the Adunis to Sainte-Germaine Railway. In early 1884 the largest of the rebel groups under Irfanic cleric Saïkou Ahmed Bamba was crushed, with any last armed resistance ceasing by the end of the year. The failure of the resistance encouraged the Euclean powers to continue their suppression of Bahian culture but envigorated the ideological beginnings of Pan-Bahianism as the weakness of a divided Bahia in the face of a strong Euclean response had been shown.

By the end of the Great War in 1935, the desire to maintain a global colonial empire and significantly diminished, especially in a now fractured and destroyed Gaullica. Most of the former empire's possessions were either transferred to Grand Alliance colonial powers - Estmere, Werania and Etruria, or gained their independence in the ensuing peace treaty. With colonialism in Estmere especially going out of the fashion, combined with the new government's desire to decolonise their colonial empire, save a few key settlements, the established colonies in Bahia began their preparations for independence. Most Bahian colonial holdings declared or gained their independence throughout the 1930s and 1940s, beginning with Djedet in 1933 and white rule effectively ending with the Treaty of Ashford in April 1950, which saw Tabora secure its independence, which until then was the final Euclean holding in Bahia.

As such, for most of Bahia, Toubacterie had ended in 1950, however in Garambura the end of Toubacterie is placed at 1969, as the rule of Rwizikuru is often seen as an oppressive one comparable to Toubacterie.

Legacy

The impacts of Toubacterie upon Bahia were widespread and continue to the modern day. The period of roughly 300 years of Euclean influence over the continent, with a century of direct control, is often cited as the leading cause of Bahia's considerable lack of development when compared with other regions of the world. Under Toubacterie the cultural, religious, ethnic, linguistic and economic landscape of Bahia was forever altered, leading to social and political issues which continue to this day.

The Euclean domains in Bahia were carved out in rather arbitrary ways, often being drawn out in boardrooms back in the Euclean capitals by people who had no knowledge of the complex demographics of the lands. When information was used, it primarily relied on geographic features such as rivers and mountain ranges. This meant that Bahia was divided with little attention paid even to the existing borders of Houregic states in the area, let alone ethnic and religious populations. The resulting holdings were therefore highly artificial constructions. In addition to this, colonial authorities often practiced divide and rule tactics. By turning ethnic groups who had previously lived more or less harmoniously together and arbitrarily distributing borders, the Euclean powers ensured that following independence these states swiftly fell into civil war. The rassemblement of different ethnic groups into artificial states can be seen in conflicts such as the Mabifian-Rwizikuran War which was fought over the majority Irfanic region of Inkiko, the Garamburan War of Independence, and the continuing Makanian Conflict. The divide and rule tactics also created conflict within states over natural resources, with the access to these being altered and granted to more loyal groups. In some cases this has even resulted in genocide, such as that of the Mirites in the Chirange.

Euclean campaigns to institute Euclean culture in Bahia were highly destructive for local cultures. The caste system was abolished, leaving a void in many areas which was not filled. Many folk religious practices and traditional ceremonies were criminalised, leading to their abandonment. Other cultural practices were also abolished, such as those relating to marriage and funerals. This led to crises of identity amongst much of the Bahian population, resulting in a phenomenon sometimes known as the Aïibe ka Djâmanou within Bahian literature. The Aïibe ka Djâmanou describes the intense feeling of longing for one's own culture and insecurity which comes with the destruction of one's identity and is shown in novels such as My Father had Six Cows by Ibrahim Barkindo. This cultural malaise is often cited as a key factor in the development of the Djeli pop musical genre, which has for its goal the renaissance of traditional Bahian culture and a new confidence in Bahian identity. Cultural destruction was also perpetrated with the theft of cultural treasures from Bahia, which were then displayed in private collections and in museums. The repatriation of these treasures has been a controversial political issue in recent times.

One of the most visible aftereffects of Toubacterie on Bahia is in the religious demographic changes. The colonial powers were prolific proselytizers, with missionaries making up a large portion of the colonial efforts. These missionaries saw immense successes, especially in Fetishist-majority east Bahia where fetishism was all but eliminated. These dramatic changes in the religious landscape resulted in the destruction of many traditional cultural practices which were seen as being heretical, a factor which played into the Aïibe ka Djâmanou. In the modern era, Sotirianity is the largest religion in Bahia, with the states of Rwizikuru and Tabora both having almost 100% of the population following the faith and almost 90% in Garambura. Irfan, once the dominant faith in Bahia, is now more or less limited to its heartland in Mabifia. The linguistic changes are equally important. Within the Gaullophonie, roughly 50% of Bahians are able to speak the language natively and most can speak some. The language forms a key lingua franca in the region, permitting communication between ethnic groups and different countries in a more neutral manner. The major outlier in this trend is Tabora, where the speaking of Weranian was criminalised upon independence.

Toubacterie was also responsible for the creation of a large Bahian diaspora across the world, primarily in Euclea and in their colonies in Asteria Inferior and Asteria Superior. The Asterian diaspora is primarily composed of the descendants of freed slaves who were brought from Bahia during the Maouhersa, the name given by Bahians to the Bahian slave trade. The effects of this population movement can be seen in nations such as Imagua and the Assimas where the majority of the population are descended from Bahian slaves. In Euclea, the diaspora is a product of imigration. Following the conflicts that marked the Kaoule, many Bahians sought refuge with their former colonists, a trend which has continued following the other wars in the subcontinent's history. One of the most notable diasporic communities is that of the Mirites, who faced intense persecution and even genocide during the First Mabifian Civil War and again in the aftermath of the Mabifian-Rwizikuran War and Second Mabifian Civil War. Many fled the country, and while large amounts fled to neighbouring Djedet and Rwizikuru many fled to Euclea. The suburb of Little Makania in Spálgleann, Caldia is home to thousands of Mirites, with many more spread across Euclea. The Bahian diaspora in Euclea are often disadvantaged, forced to live in lower income areas and face racism and discrimination on account of their skin colour. This is accentuated by far-right populism, with groups such as the Tribune Movement in Etruria rallying against Bahian immigration. The Bahian diaspora is highly influential in the sphere of popular culture, with an effect on music and fashion. A large amount of Bahians also leave for economic reasons, which has been criticised both by Euclean leftists and Pan-Bahianist intellectuals as contributing to brain drain and the slowed development of Bahia.