Great War (Aurorum)

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

| Great War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

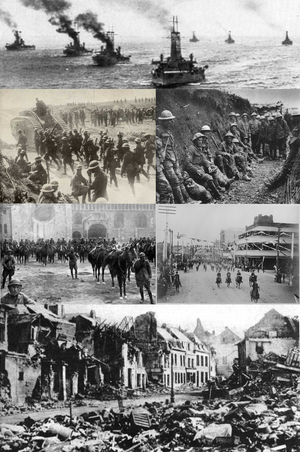

(Clockwise from the top)

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Armala Coalition |

Central Alliance | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Total: 3,920,294 |

Total: 10,023,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Military dead: 495,204 Military deaths by country |

Military dead: 1,736,852 Military deaths by country | ||||||

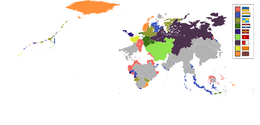

The Great War, also known as the Great Berean War or the World War, was a significant global conflict primarily between nations in Siantria and Telmeria in Berea and overseas in Caphtora and Pamira, that lasted from 1910 to 1916. Having reached a never before seen scale, it led to the mobilisation of more than 20 million military personnel, making it one of the largest wars ever fought. With an estimated three million combatants and one million civilian deaths as a direct consequence of the war, it is also one of the deadliest conflicts in history. The conflict began on September 7, 1911 following X. It lasted until the unilateral surrender of remaining Central Alliance powers on May 29, 1916 and peace was declared following the Treaty of Lehpold in early 1917.

TBD

The Continental War at large was a political, economic, cultural, and social turning point for the world. it is generally considered to mark an end to the age of colonial empires in Berea, and saw the dissolution of multiple influential states and the deterioration of others' powers. The war and its immediate aftermath saw a number of revolutions and uprisings in Dulebia, Cuthland, Mascylla, and X. Through the political instability, the Big Three (Albeinland, Lavaria and Mascylla; the principal X members and war victors) emerged their power as great powers and imposed their demands on the defeated enemies in a treaty drafted and signed in 1917—the Treaty of Lehpold. Ultimately, the intergovernmental organisation of the Assembly of Nations was founded to spearhead international cooperation and to prevent another large-scale conflict.

Background

| Events leading to the Great War | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Political atmosphere and ambitions

Dulebian and Cuthish partition of Rovina

Dulebo-Lavarian rivalry

Colonial ambitions of Dulebia and Cuthland

Arms race

Tensions in Berea

Prelude

The war

Western Front

Dulebian offensive and entrenchment

The armed conflict in the west between the Dulebian and Lavarian armies began on 25 September 1911, 15 days after the declared full mobilization of Dulebian forces. According to the Dulebian pre-war plan, Operation XX, more commonly known as Operation Rassvet, the Dulebian army was almost entirely stationed on the Lavarian border, with the bulk of the forces situated to the south on the Volynsk plain. The Dulebian command left its northern flank relatively weakened, and planned to use the river Lena as a natural barrier and defence frontier. This positioning of the Dulebian forces was used to lure the Lavarian forces to attack on that part of the front, leaving the south mostly undefended against the main Dulebian advance.

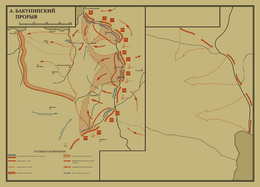

The Dulebian right flang was ordered to retreat towards Lena on 26-28 September, this retreat was followed by a Lavarian attack, as planned by the Dulebians. Then, on 29 September, the Dulebian offensive was launched on the left flank by the 2nd Field Army of General Kuznetsov and 3rd Field Army of General Bakunin. The two armies met severe Lavarian resistance on the river Lena, where the Lavarians constructed a fort near the town of Granita. The siege of Granita was the first major battle of the campaign, and slowed the Dulebian advance by two days, giving time for Lavarian command to form new army in the south and march it to the Dulebian border. Simultaniously with the armies of Kuznetsov and Bakunin, 4th Field army under Birulyov, originally kept as reserve to protect the southern frontiers of Dulebia against possible intervention from the Gurkhan empire, was ordered to cross the Lavarian border and attack the Lavarian reinforcements marching from the south, protecting the left flank of 2nd and 3rd armies. The advance of Bakunin and Kuznetsov was halted near the city of Montalvia; the Dulebian forces, who managed to march almost 120 km into Lavaria in less than a week, overstretched their supply lines and the soldiers were exhausted from the rapid advance. The communication lines of the Dulebian forces have not been established. However, the Lavarian forces already started to regroup and a significant portion of their armies were stationed near Montalvia. Facing the risk to lose momentum, Bakunin ordered his forces to cross river Montalvia and mit the Lavarians head-on without reinforcements or an established supply chain. In the resulting Battle of Montalvia, Dulebia faced the first major defeat in the campaign, and its advance was stalled.

Following the Dulebian defeat at Montalvia, the Gurkhan empire, which remained neutral since the start of the war, declared war on Dulebia and invaded the Muromo-Pomorsk Kingdom on 4 March, meeting almost no resistance as all Dulebian forces were sent to the Western front. These events forced the Dulebian command to stop all advances and initiate a regrouping of its forces. General Milyukov, commander of the 1st army on the Dulebian right flank, who sat in defence behind Lena since the start of the campaign, was ordered to attack and push towards Aniarro as it was believed the Lavarian presense there was limited after the regrouping of Lavarian forces near Montalvia. At the same time, 2nd army of Kuznetsov, which already managed to establish stable supply chain, received orders to turn north and connect with Milyukov, attempting encirclement of the Lavarian forces between Bakunin's 3rd army and the Karsk sea coast. Lavarian forces attempted a similar maneuver to encircle the advancing forces of Milyukov. As both forces raced towards the Karsk sea, they had to leave significant amount of forces on the newly-forming frontlines in order to protect their flanks from possible encirclement attempts by their opponent. As a result of this operation, the frontline was stretched even further and in the end it was stalled; both Lavaria and Dulebia found themselves in a stalemate and began entrenching to preserve their current positions.

Winter offensive of 1912 and the frontline stall

The Dulebian forces were very disorganised after the defeat at Montalvia and the following race to the sea, and suffered from very low morale due to the heavy casualties of the first weeks of the conflict. The early advances in Lavaria led to the destruction of the rail and road network, leading to serious problems with supply on the Dulebian side. Besides that, the Lavarian forces, which experienced even heavier casualties, managed to finish their mobilization in early December, and planned a winter counter-offensive in January on the northern section of the front, where the Dulebian defence seemed the weakest. Lavarians concentrated a vast force of almost one million men on the Aniarro-Montalvia section on the front, and launched an offensive on 31 January 1912. Dulebian High Command, due to its inability to request troops from the Southern Front, was forced to call for a retreat back to the Dulebian border and further inland to the river Lena, as was initially planned in case of a failure in the beginning of the war. During their retreat, Dulebian forces deployed scorched earth tactics and completely destroyed the infrastructure of the Guefa region. Regardless of their enemies' retreat, Lavarian forces met heavy resistance during their advance, and lost almost half of the initial force upon reaching the river Lena. They were forced to stop at Lena, since they didn't have the manpower to cross the river and meet the heavy pre-war defence line of the Dulebian empire on the right bank. At the same time, Lavarian attempts to also destroy the Dulebian forces on the southern section of the front ended as complete disaster. As a result of the Winter offensive, Lavaria lost 650,000 men dead, wounded or missing. The deployment of scorched earth tactics by the Dulebians left most of of the frontline completely worthless, hard to defend, and forced Lavaria to waste a vast amount of resources to repair the destroyed infrastructure. All these factors initially made it hard for Lavaria to perfom fast relocations of troops as it could in 1911. The frontline stalled after the Winter offensive for the next year.

Both sides needed several months to recover from the Winter offensive. Between March and December 1912, Dulebian forces under Bakunin attempted to cross Lena three times, but all resulted in a bloody failure. These crossings are now known as the Three Battles of Ust-Borovsk. Identical attempts of Lavarian forces on the southern section of the front, namely the Armala Offensive of July-October 1912 resulted in similar failures, with the Lavarians managing to gain only a small portion of land on the Armala gulf coast of little strategic value, at the expense of 50,000 dead Lavarians. The prolongued trench warfare of 1912 and the resulting stalemate of the Western front in that period, however, had a serious effect on the living conditions of the soldiers in both armies. Diseases like flu, trench fever, on par with numerous parasytes like body lice, psychological traumas and disorders like shell shock, and traumas caused by the armed action itself, especially by chemical weapons like chlorine and mustard gas both significally lowered the troop morale and caused thousands of casualties even outside of combat. The low morale in the Dulebian army eventually led to the spread of various radical political ideas and unrest among the troops and their families at home. Undercover political powers, most notably the far-left communists of Viktor Shchyukin, used the situation to agitate against the war and for a revolution among the frontline troops. As the war progressed, these ideas became more and more popular on the Western front, where the Dulebian empire was the least successful during the conflict. This eventually led to the Dulebian revolution in 1914.

Bakunin's offensive and the Dulebian revolution

The front stalemate continued into 1913, with both sides failing to win decisively. By February 1913 Mikhail Bakunin, the commander of the Dulebian fourth army, proposed a shock attack on the whole length of the front with the usage of brand new tactics for the era. Bakunin was promoted to field marshal and commander of the whole Western front in March 1913, his plan was accepted by the emperor himself, and mass mobilization in preparation for the operation commenced in mid-March. The mobilization was finished on the 15th of May, 1913. Almost 5.3 million men were mobilized, which was equal to 21% of the Dulebian pre-war population. 3 million men were stationed on the Western front on two sections, with the majority of the manpower focused in the north behind the river Lena, where the frontline stood since 1912. The operation was planned to be launched in August 1913, however, due to several defeats of the Cuthish forces against Mascylla and the information about three Lavarian armies being transported to aid Mascylla on the Northern front, Bakunin was forced to launch the offensive on 26 May, 1913.

Dulebian divisions crossed the Lena in the morning of 26 May, and managed to inflitrate the Lavarian trenches on the left bank of the river in several points of the front, most notably at Ivanovo and Ust-Borovsk. Dulebian forces failed to cross Lena in several places, where the Dulebian casualties reached 5,000 in the first day of the operation. Nevertheless, until 31 of May, Bakunin had a stable lodgements in three sectors of the ront, from which the Dulebian forces continued their advance. The key cities of Bravara and Baranca were reached and captured already before 10 June, and the rapid advance continued throughout June. Dulebian forces were forced to stop only at Aniarro, the capital of Lavaria, on 31 June. In the same time, at the southern front the Armala offensive was launched almost immediately after the Bakunin offensive, with the key objective of reaching Armala, key port of the Lavarian navy. Dulebian forces on this part of the front were commanded by General Kirilov, who was not as experienced in maneuver warfare. s a result, Dulebia had only minor success in the Armala offensive, only breaking 100-150 km into Lavarian positions, while facing almost the same amount of casualties as the sector under Bakunin.

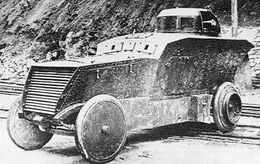

Bakunin's offensive is seen as the peak of Dulebian effort in the Great war, and is often named as the breaking point in the war for the country. On one side, the huge success of the operation can be explained by the outstandingg tactics proposed and executed by Bakunin: Dulebian forces relied on short, accurate artillery barrages, rapid advances of small specialist groups followed by the main forces, a tactic later known as infiltration. Armoured vehicles like armoured cars, light and mobile artillery pieces, the extensive use of early improvised self-propelled guns, and the first active usage of air support in the war, and the attempt to use highly-motorized supply vehicles, all are seen as major contributors in the Dulebian victory on tactical level and would later become the basis for the Dulebian shock and infiltration tactics of the mid-20th century. Bakunin himself would become a renowned supporter of the idea of modern warfare and a pioneer of the usage of tanks in the Dulebian People's Army after the Dulebian civil war. On the other side of the coin, however, are the casualties suffered by Dulebia, which were the highest since the beginning of the war, reaching 450,000 dead, wounded or missing by July 1913. On par with previous low morale of the Dulebian forces, the heavy casualties in the operation and the limited success of the Armala offensive, led to first riots in the troops. To worsen the situation, in September 1913 Bakunin and most of the veterans of the operation were transferred to the Valimian border in preparation for Operation Luch, while the Western front was given to Field Marshal Ilya Shchors, the old commander of the Army Group North who showed little-to-no success against Valimia ever since the start of the war, and is generally described as a poor commander who refused to implement the new technologies introduced during the conflict, relying on outdated cavalry attacks and mass infantry doctrine. The breaking point was the defeat of Dulebia in the Battle of Aniarro, where the forces of Shchors failed to cross the river Aniarro, and suffered from heavy casualties, the heaviest inflicted to Dulebia in a single battle since the beginning of the war. This led to the outbreak of the Dulebian Revolution in February 1914 in Ulich and Kamianets. The royal family was arrested by the revolutionaries on 13 February, and the Dulebian Civil War begun the same month between royalists and radical communist revolutionaries under Shchyukin. In these conditions, the Western front collapsed in February, a situation used by Lavaria to start a massive offensive, which saw very limited resistance from Dulebians. Lavarians crossed Lena by March 1914, and even besieged Spassovsk and Novocherepovets. The Dulebian communist party under Shchyukin, which needed to focus all of its forces in the civil war, asked for peace.

Following the Ulich peace treaty of 1914, Dulebia gave up all of the territory captured since 1911, the city of Bravana, captured by Dulebians in 1870, and most of its territories on the Endotheric sea, most notably the Muromo-Pomorsk kingdom. The defeat of Dulebia and the collapse of the Western front left Cuthland as the last major combatant in Berea. The fall of Dulebia led to the collapse of the Cuthish effort in less than a year, the war ended in 1915.

Eastern Theatre

Northern Front

Cuthish advances

Trench warfare and progress of the war

Valimian front

Before the outbreak of the war, Valimia was not considered a significant threat by both Dulebian and Cuthish military commanders. Valimia was lacking severely behind the Berean powers in terms of equipment, discipline and infrastructure. It was expected that the mobilization of the country would take up to two months, time sufficient enough to invade the important industrial region of Rovina and establishing a defensive line there. The attitude of the Dulebian military elite towards Valimia and its armed forces was clearly expressed by Yury Shtass, field marshal of the Dulebian army in the outbreak of the war and the author of the Operation XX, in his dialogue with the Emperor of Cuthland in 1909:

The question of possible Valimian involvement in the incoming war could not be less interesting for me. The Valimian army is underequipped, untrained, disorganised, and led by completely incompetent officers. If Valimians decide to join our effort, I'll need four divisions to aid them against Mascylla in Adwhin. If they decide to oppose us in the war, I'll need four divisions to push them out of Rovina.

The low opinion of the Central powers is partially understandable: at the time, Valimia was severy lacking behind the Berean powers in terms of technology; the Valimian tactics were outdated, and the country fielded a very small fleet that couldn't counter the Cuthish White sea fleet. Apart from that, the soldiers of the country suffered from very low morale which was even encouraged by the commanding officers after the beginning of the war: soldiers were rarely given rest between battles, and the Valimian propaganda among their own troops was practically unexistant. In these conditions, the Valimian army showed poor results already in the 19th century during the armed conflicts with Cuthland and Dulebia in Rovina, when the country lost small portions of land to the future Central powers.

Before the start of the war, Dulebia prepared a 5th army under General Ilya Shchors. The army consisting of 4 divisions was split between two sections of the Valimo-Dulebian border: 2 divisions were stationed on the Vitevsk-Knyazy Stan line, and two in the mountains around Tsaritsyn. Upon declaration of war by Valimia, the 5th Army of Shchors entered Valimia, with the first two sections ordered to capture Ritavice and stop at the river XX, while the other two were tasked with pushing the Valimian forces to the northern banks of the rives YY and ZZ, and capturing the strategic city of Jarowiec. The operation lasted 7 months and eventually led to only limited success: Dulebian forces reached the river XX in the west, but failed to capture Ritavice, their primary objective. The eastern section performed even poorer, barely managing to leave the mountainous Riliva region only to be met by a well-prepared defensive line in southern Rovina, where it was forced to entrench and halt its advance due to severe casualties. The progress of the war on the Western and Southern fronts made it clear that Shchors can receive only limited reinforcements: he was forced to halt any advances and try to hold the territory already under his control until the high command could send him reinforcements.

This situation was exploited by the Valimian forces: in March 1912, parallel with the Gurkhan invasion of Southern Dulebia, the Valimians launched the First Riliva Offensive against the two divisions in southern Rovina, with the primary objective to push the Dulebian forces in this section of the front back to the Riliva mountains. This battle, however, proved the poor state of the Valimian army: while having more men and artillery on this section of the front (Valimians prepared almost five fully-equipped divisions against the two divisions Dulebia stationed here since the outbreak of the war), General Aksel Airo failed to penetrate even the first defensive line of the opposing forces for almost two weeks, and ultimately his forces managed to penetrate into the dulebian lines only 2-3 km on most of the frontline's length. Valimians attempted to attack the Dulebian defenses in the region 4 times in total between 1911 and early 1913: the first two Battles of Borowice were repelled by the Dulebians, who nonetheless suffered from heavy casualties. The Third Battle of Borowice remains the bloodiest battle of the Valimian forces, where both sides lost between 50,000 and 75,000 men each, while the battle itself remained almost indecisive. The Fourth Battle of Borowice was the first major success of the Valimians on the offensive: the Dulebian defenses in South Rovina were broken, and Shchors was forced to retreat to the Riliva mountains, where they had a decisive advantage of the hard terrain of the mountainous region.

In June-August 1913, General Akself Airo attempted to assault the Dulebian forces near Ritavice on the Western section of the front. This advance proved unsuccessful, as the Dulebians had the advantage of the river XX serving as natural barrier and a first level of their defense. Badly blooded, Valimians retreated from Ritavice; the city itself fell to the Dulebian counter-attack the same month as Airo had no troops left to defend it. When the inability of Valimia to continue the war became obvious to the Dulebian High Command, the decision was taken to start an offensive on the Valimian front. Following the grand success of Bakunin during the Breakthrough on the Western front, he was transferred to Valimia together with 5 divisions of veteran troops from the Western and Southern fronts. Dulebians launched an attack from Ritavice, supported by Cuthish troops under the command of ZZ, on 5 September 1913. Valimians, unprepared for the rapid advance of Bakunin, and suffering from lack of equipment, medicaments, and reinforcements, were quickly pushed back to Mirkovice. The cities of Mirkovice, Jarowiec and Biestrzyn were occupied by December 1913.

Even the severe winter conditions in Rovina could not stop the advance of Bakunin, which continued into the first months of 1914. The collapse of Valimia was used by Cuthland to launch a strategic operation in Adhwin. Valimia was already prepared to ask for peace as the Dulebian forces were reaching the Valimian mountains, the last natural border between them and the capital of the empire in Paavalpori. However, with the outbreak of the Dulebian Civil War, Field Marshal Bakunin took the decision to stop the advance and turn his forces back to Dulebia to protect Erjarvia and join the Civil war, performing the Great Bakunin's March. This decision had proven vital for the fate of the Cuthish forces on the Eastern Front: as Bakunin left, both Valimia and Mascylla used the momentum to launch counter-offensive operations on the whole length of the front against the outnumbered Cuthish army. The Rovinian region itself saw increased civil unrest as Rovinians tried to gain independence from both Dulebian and, later on, Valimian rule, which was largely ignored by the Dulebians in 1914 due to their own civil war, but was repelled by the Valimians in 1915-1916.

Southern Front

Early Gurkhan advances

At the outbreak of the war, the Gurkhan Empire suffered from a political crisis: the Sultan, Selim IV, was in favour of joining the Allied forces and attacking Dulebian possessions in Pomoria, taken from the Gurkhans following the Dulebo-Gurkhan war of 1899-1901. In the same time, the Grand Vizier Mehmed Sadık Pasha was in favour of the Central powers. The strategic position of the Gurkhan empire threatened the communications of Lavaria and Mascylla with their colonies in Eastern Pamira. The Gurkhans possessed a strong navy in the Endotheric sea, which could aid the Dulebians if the country was to ally with them. Such a strategic position led to the struugle of both blocs to ensure the support of the Gurkhans. In the first week of April, the Grand Vizier died mysteriously after an audience with Lavarian diplomats in Hasenta. In the following two weeks, the Gurkhan empire began mobilising troops on the Dulebian border, and on 29 April it ceased all diplomatic relations with the Dulebians. On 4 March, 1911, the Gurkhanate declared war on Dulebia, and its armies marched into the Muromo-Pomorsk Kingdom. This maneuver was undertaken by Selim IV to aid the Lavarian forces on the Western front. As historians suggest, Selim was most probably promised the majority of Pomorian lands in exchange of an immediate attack against Dulebia.

The Gurkhan forces suffered from lack of equipment and low morale, but still managed to score several important victories against the Dulebian force which was very limited in size; the majority of the Dulebian manpower was located on the Western and Valimian fronts, the Gurkhans were not treated as threat by the Dulebians. The Gurkhan forces captured the city of Bakhchi-Sarai on 16 March, and reached the Haydushki mountains on 17 March. The Dulebian 4th Army under Birulyov was ordered to dispatch half of its strength into a new 5th Army under general Kruzenshtern. Kruzenshtern was ordered to march south to stop the Gurkhan advance and protect the port of Balchevsk. In the same time, the Gurkhan advance on the Tayari front reached past the Verkhoyansk plateau: the forces of General Suleiman Pasha reached Ekaterinoslavl: one of the biggest Dulebian cities and a major causeway in the Dulebian south. The small garrison of the city, composed of 5,500 soldiers, 1,200 policemen, and several thousand volunteer militia, met the force of 22,000 Gurkhan soldiers. The city was besieged, but ultimately the Gurkhans failed to completely cut it off the supplies from the north; furthermore, Gurkhan attempts to enter the city on 28-31 March ended as crushing defeat, the Gurkhan forces lost almost one third of their forces. Gurkhans were forced to retreat from the city in the first week of April after the defeat of the First army near Balchevsk: fearing a possible surrounding, the Gurkhans in the Haydushki mountains withdrew from the city of Ekaterinoslavl.

Kruzenshtern used the retreat of the Gurkhans to regroup and prepare a counter-offensive on his own. In the first hours of May 1911, Dulebian troops attacked Gurkhan defense positions in the Verkhoyansk plateau and marched inland into the Gurkhanate, threatening the city of Șaparkorum, a major port of the empire. The advance of Kruzenshtern, known as the Haydut offensive, proved to be a grand success: Gurkhan forces were pushed almost 180 km inland. The advance of the Dulebian forces was supported by various Pomorian armed militias; some of them conducted partisan warfare against the Gurkhanate armies. The forces of Suleiman Pasha responed with a number of repressions in villages and towns in the region between May and July, until when they were pushed out of Pomoria. The result of these war crimes was the further consolidation of locals against the Sultan and his rule.

Landings at Balchevsk

Collapse of the Gurkhan empire

Other fronts

Melasia

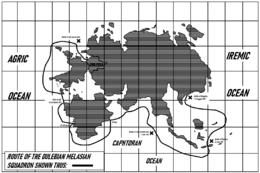

Since the outbreak of the war, Dulebia was unable to reinforce the small garrison of merely 2,000 Dulebian soldiers and 3,000 local policemen stationed in Dulebian Melasia. This was used by Mascylla, which attacked the islands and besieged the port town of Aleksandrovsky, the most important city in the colony, which was also the best-defended settlement outside Dulebia. The small Mascyllary Melasian squadron met heavy resistance from the coast guard of the port, was composed of ten gunboats and two armoured cruisers. Between 12-15 October 1911, the Mascyllary colonial squadron under Admiral Alfred, Crown Prince of Welsbach, attacked the Dulebian squadron under Admiral Bokalov and shelled the city of Aleksandrovsky. During the battle, the Mascyllary forces lost one cruiser, while Bokalov lost four gunboats to enemy fire, with three more being damaged and one being scuttled. The two cruisers of Bokalov managed to escape the city harbour under the cover of night on 16 August and moved to the town of Takawa. Left unprotected from the sea, the city was besieged from the Mascyllary forces, but refused to surrender for two weeks. The forces of the Crown Prince attempted two direct attacks against the fortified walls of the city, both times failing and suffering from serious casualties. In 16 days since the beginning of the siege, the commandant of Aleksandrovsky, Vitaly Klugenfort, decided to give up the fortress because of the starvation of his forces, which were left without supplies. Mascyllary forces continued to Takawa, where they met no resistance from the small garrison. At Kalintan, 2,500 Mascyllary soldiers met a Dulebian garrison of 520 soldiers and 280 policemen, who barricaded themselves in the town hall and refused to surrender. After a several hour fight, the town hall was captured and the remainder of Dulebian troops were captured.

In desperate attempt to save their colony in Melasia, Dulebian High Command dispatched a part of the Karsk sea fleet while it was on its way to the Karsk sea gate to take part in the battle, a decision which, according to some historians, proved vital for the outcome of the battle. The expeditionary squadron under Admiral Glazkov refueled in the Carra Republic, and later sailed around Albeinland on route to Melasia. The squadron consisted of seven ships: two dreadnoughts, four destroyers, and one of the three newest battleships of the country, Admiral Rzhanevsky. The squadron stopped for another refueling in Caphtora, and later harassed allied shipping in the Caphtoran ocean, raiding several Lavarian colonial ports and shelling the city of X in Eastern Caphtora. Unaware of the force of the squadron, Mascylla sent Admiral Alfred along part of the Mascyllary Melasian squadron to intercept the Dulebian ships in the Caroline sea. In the Battle of Caroline sea, the Dulebian squadron sunk 3 Mascyllary destroyers and one pre-dreadnought, effectively wiping out half of the Mascyllary navy in Melasia. The Dulebian squadron reached the Tarokan sea two weeks later, only to find that the city of Vostok, the last Dulebian port in Melasia, was already partially captured by the forces of General Karl Georg von Pritnitz. The ships of Glazkov retrieved several hundred refugees and soldiers from the city, added the last remaining cruiser of Bokalov to the squadron and fled to Nanzhou to refuel. On their way through the Tarokan strait, they were intercepted by the remainder of the Mascyllary Melasian squadron under Helmuth von Kraisach, in a daring attack. Von Kraisach expected the Dulebian ships to be damaged since the engagement in the Caroline sea and to be running low on ammunition. However, his entire fleet was sunk in the battle that lasted three hours; Dulebia lost one destroyer and several other ships took light damage, but were able to continue to Nanzhou. Von Kraisach died during the battle when his ship, the pre-dreadnought MSS Markgraf, was critically hit in the casemate and suffered from an explosion of the ammunition rack in the opening hour of the battle.

Nanzhou

Following the defeat of Dulebia in Melasia, its Melasian squadron disengaged to Pavlovsk-Vostochny, the last remaining Dulebian colonial port in the Eastern hemisphere. The port was an important asset of the empire, and was well equipped with both ammunition and coal, and had a repair facility for the Dulebian military ships. The squadron under Glazkov, which previously destroyed the Mascyllary colonial squadron in the Tarokan sea, now received an order to stay in the city and protect it at all costs. At the same time Nonzhao, the leader of which was aware of the Dulebian defeat in Melasia, decided to join the XX to recapture the valuable city of Pavlovsk. Nanzhou declared war on Dulebia on 16 March, 1912, and sent most of its fleet under Admiral Shaokuan, as well as an army to besiege the port. The fleet reached the city and intered the Bay of Dongdao on 20 March, 1912. The Nanzhouese fleet numbered 25 ships, almost dounble the size of the Dulebian expeditionary squadron of Glazkov. However, while Glazkov fielded several modern battleships and dreadnoughts on par with smaller gunboats and destroyers, the Nanzhouese fleet only had outdated ironclad ships which stood no chance against the Dulebian navy. Shaokuan attempted a surprise attack in the early morning of 22 March 1912, but was spotted by Dulebian balloon and lost the element of surprise, vital to his tactic. The Nanzhouese navy suffered a crushing defeat, during which 21 ships were lost to enemy action, and Admiral Shaokuan was forced to retreat. In the same time, the land siege of the Nanzhouese suffered a similar faith, with the army of General YY failing its primary objective of capturing hill Baranova Sopka on the outskirts of the city, where a small Dulebian garrison was stationed. With the defeat of the Nanzhouese fleet, Dulebian ships used their superiority to shell Nanzhouese positions and support the Dulebian garrison on Baranova Sopka. The squadron of Glazkov also managed to secure a steady supply chain from Kenlong, which joined the war on the side of Dulebia and Cuthland one month earlier. Following the complete defeat of Nanzhou in the Battle of Dongdao, the city remained uncontested for the next 4 years, only surrendering to the Mascyllary navy in 1916 after the end of the war.

The defeat of the Nanzhouese navy was used by Glazkov. Following the Battle of Dongdao, the expeditionary squadron left the port bay and headed to Mascyllary Kenlong, where the ships of Glazkov supported their Kenlongese allies during the sieges of Dong Hoa and Da Pha. Two ships of the squadron, namely the destroyer Preobrazhenets and the dreadnought Neustrashimy were detached from Glazkov's fleet in late-1912, and sailed to the Caphtoran ocean to hunt down allied merchant shipping. The rest of the fleet under Glazkov continued its limited operations in Kenlong and the Saba sea until early 1914. When news of the revolution at home reached them, Glazkov took the decision to station the ships back in the bay of Dongdao. Following the defeat of both Dulebia and Kenlong, the port started to experience supply shortages, ultimately leading to the beaching of the ships of the expeditionary squadron and their use as static defenses during the Second Siege of Pavlovsk-Vostochny. The city managed to withstand the Nanzhouese siege again, but was forced to capitulate when the Mascyllary High seas fleet entered the Bay of Dongdao in early 1916.

Caphtora

Dulebian cruiser hunters

Karsk sea

Aftermath

Peace treaties and geopolitical changes

Treaty of Lehpold

Main article: Treaty of Lehpold

See also

- ↑ Prior to the Bakunin's Breakthrough in May 1913