Huang dynasty: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (95 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Constitutional monarchies]] | [[Category:Constitutional monarchies]] | ||

[[Category:Countries]] | [[Category:Countries]] | ||

[[Category:Huang dynasty]] | [[Category:Huang dynasty]] | ||

[[Category:Monarchies]] | [[Category:Monarchies]] | ||

[[Category:MT]] | [[Category:MT]] | ||

[[Category:Nev's Article]] | [[Category:Nev's Article]] | ||

{{WIP}} | {{WIP}} | ||

{{Infobox country | {{Infobox country | ||

| Line 22: | Line 18: | ||

|symbol_width = | |symbol_width = | ||

|alt_coat = <!--alt text for coat of arms--> | |alt_coat = <!--alt text for coat of arms--> | ||

|symbol_type = Imperial Seal | |symbol_type = [[National seals of Jinae|Imperial Seal]] <!--Make a page for the flag of Da Huang as well, also note that the Imperial Seal is the Heirloom Seal of the Realm--> | ||

|national_motto = | |national_motto = | ||

|national_anthem = <br>永恒軍軍歌 <br>''Yǒnghéngjūn jūngē''<br>"{{wp|Anthem of the Beiyang Fleet|Anthem of the Everlasting Army}}"<br>[[File:MediaPlayer.png|link=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fXpGpgYHj1k|210px]] | |national_anthem = <br>永恒軍軍歌 <br>''Yǒnghéngjūn jūngē''<br>"{{wp|Anthem of the Beiyang Fleet|Anthem of the Everlasting Army}}"<br>[[File:MediaPlayer.png|link=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fXpGpgYHj1k|210px]] | ||

| Line 33: | Line 29: | ||

|map2_width = 275px | |map2_width = 275px | ||

|alt_map2 = <!--alt text for second map--> | |alt_map2 = <!--alt text for second map--> | ||

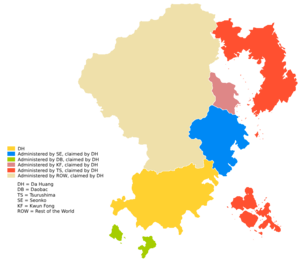

|map_caption2 = Political Map of Da Huang | |map_caption2 = Political Map of Da Huang circa 1930 | ||

|capital = [[Basingse]] | |capital = [[Basingse]] | ||

|largest_city = [[ | |largest_city = [[Suicheng]] | ||

|official_languages = {{wp|Standard Chinese|Standard Jin}} | |official_languages = {{wp|Standard Chinese|Standard Jin}} | ||

|languages_type = {{wp|Official script}} | |languages_type = {{wp|Official script}} | ||

| Line 44: | Line 40: | ||

|religion = {{plainlist| | |religion = {{plainlist| | ||

* {{wp|Legalism (Chinese philosophy)|State Legalism}} ({{wp|State religion|official}}) | * {{wp|Legalism (Chinese philosophy)|State Legalism}} ({{wp|State religion|official}}) | ||

* 74.5% [[Jin folk religion|Folk | * 74.5% [[Irreligion in Da Huang|Irreligious]] / [[Jin folk religion|Folk]] | ||

* 18.3% [[Jin N'nhivaranism|N'nhivaranism]] | * 18.3% [[Jin N'nhivaranism|N'nhivaranism]] | ||

* 5.2% [[Christianity in Da Huang|Christianity]] | * 5.2% [[Christianity in Da Huang|Christianity]] | ||

| Line 86: | Line 82: | ||

|established_date8 = 1674 | |established_date8 = 1674 | ||

|established_event9 = Wucheng Heavenly Rebellion | |established_event9 = Wucheng Heavenly Rebellion | ||

|established_date9 = | |established_date9 = 1900—1902 | ||

|established_event10 = Republic of Jin established | |established_event10 = Republic of Jin established | ||

|established_date10 = 1902—1931 | |established_date10 = 1902—1931 | ||

| Line 120: | Line 116: | ||

}} | }} | ||

The '''Huang dynasty''', officially the '''Great Huang''' (Jin: 大黄; pinyin: ''Dà Huáng''), is a {{wp|sovereign state}} in Southeast Ochran, situated in the Jin Peninsula, spanning 1,125,344 square kilometres (434,498 sq mi), with a population of 121,648,117. The country is bordered to the northeast by [[Seonko]] and shares maritime borders with [[Daobac]] to the south and [[Tsurushima]] through the Kaihei islands to the east. The national capital is [[Basingse]], and the most populous city and largest {{wp|financial centre}} is [[ | The '''Huang dynasty''', officially the '''Great Huang''' (Jin: 大黄; pinyin: ''Dà Huáng''), is a {{wp|sovereign state}} in Southeast Ochran, situated in the Jin Peninsula, spanning 1,125,344 square kilometres (434,498 sq mi), with a population of 121,648,117. The country is bordered to the northeast by [[Seonko]] and shares maritime borders with [[Daobac]] to the south and [[Tsurushima]] through the Kaihei islands to the east. The national capital is [[Basingse]], and the most populous city and largest {{wp|financial centre}} is [[Suicheng]]. | ||

Modern Jin traces their origins to a {{wp|cradle of civilisation}} in the fertile [[Yellow River]] basin in the [[Central Jin Plain]]. Their long occupation, initially in varying forms of hunter-gatherers, emerged into settled life as early as 7000 BCE, gradually evolving into multiple early Jin civilisations. The interactions of different and distinct cultures and ethnic groups influenced each other's development; specific cultural regions that developed the early Jin civilisation were the [[Huanghe civilisation]], the [[Chiangjiang civilisation]], and the [[Nanbei culture]]. | Modern Jin traces their origins to a {{wp|cradle of civilisation}} in the fertile [[Yellow River]] basin in the [[Central Jin Plain]]. Their long occupation, initially in varying forms of hunter-gatherers, emerged into settled life as early as 7000 BCE, gradually evolving into multiple early Jin civilisations. The interactions of different and distinct cultures and ethnic groups influenced each other's development; specific cultural regions that developed the early Jin civilisation were the [[Huanghe civilisation]], the [[Chiangjiang civilisation]], and the [[Nanbei culture]]. | ||

| Line 130: | Line 126: | ||

Throughout its existence, the Jin dynasty expanded, fractured, and reunified; was conquered and reestablished; absorbed foreign religions and ideas; and made world-leading scientific advances, such as the [[Four Great Inventions]]: {{wp|Gunpowder|gunpowder}}, {{wp|Papermaking|paper}}, the {{wp|Compass|compass}}, and {{wp|Printing|printing}}{{efn|The Four Great Inventions ([[Simplified Jin characters|simplified Jin]]: 四大发明; [[Traditional Jin characters|traditional Jin]]: 四大發明; {{wp|Pinyin|pinyin}}: sì dà fā míng) are inventions from [[History of Da Huang#Ancient Jin|ancient Jin]] that are celebrated in [[Jin culture]] for their historical significance and as symbols of Jin's {{wp|Golden age (metaphor)|golden age}}. However, modern scholars have disputed the veracity that the Jin was the first to develop these innovations. The historical facts regarding the origin of some of these inventions remain scant, and several competing arguments have been raised to challenge these claims. Most notably:{{Bulleted list|{{wp|Gunpowder}} has been used extensively in the [[Tahamaja Empire|Tahamaja empire]] since the mid-11th century. The medieval navies of the Tahamaja were recorded to have mastered using rudimentary artillery to solidify their rule across their vast maritime empire. While the Song dynasty (907–932) in Da Huang has been purported to have used explosive substances in cannons, fire arrows, and other military weapons, scholars have posited that their military use was not as extensive as once thought and that these weapons only saw comprehensive service during the Zheng dynasty (932–1358) in the late 13th century. There is an increasingly growing argument that the Tahamaja empire was the first to discover the invention of gunpowder, and its manufacturing methods were brought to Da Huang by their interaction. Another purported argument is that the innovation was concurrent, and both the ancient Jin and Tahamaja developed gunpowder simultaneously around the same time.}}}}. However, by the late 6th century CE, centuries of disunity led to the fall of the Jin. The following [[Zhou dynasty|Zhou]] (581–618) and the [[Later Wei dynasty|Later Wei]] (618–907) dynasties would reunify the empire. The xenophilic Later Wei welcomed foreign trade and culture across the Kayatman Sea and the Jade Road and adapted [[N'nhivara|N'nhivaranism]] to Jin culture. | Throughout its existence, the Jin dynasty expanded, fractured, and reunified; was conquered and reestablished; absorbed foreign religions and ideas; and made world-leading scientific advances, such as the [[Four Great Inventions]]: {{wp|Gunpowder|gunpowder}}, {{wp|Papermaking|paper}}, the {{wp|Compass|compass}}, and {{wp|Printing|printing}}{{efn|The Four Great Inventions ([[Simplified Jin characters|simplified Jin]]: 四大发明; [[Traditional Jin characters|traditional Jin]]: 四大發明; {{wp|Pinyin|pinyin}}: sì dà fā míng) are inventions from [[History of Da Huang#Ancient Jin|ancient Jin]] that are celebrated in [[Jin culture]] for their historical significance and as symbols of Jin's {{wp|Golden age (metaphor)|golden age}}. However, modern scholars have disputed the veracity that the Jin was the first to develop these innovations. The historical facts regarding the origin of some of these inventions remain scant, and several competing arguments have been raised to challenge these claims. Most notably:{{Bulleted list|{{wp|Gunpowder}} has been used extensively in the [[Tahamaja Empire|Tahamaja empire]] since the mid-11th century. The medieval navies of the Tahamaja were recorded to have mastered using rudimentary artillery to solidify their rule across their vast maritime empire. While the Song dynasty (907–932) in Da Huang has been purported to have used explosive substances in cannons, fire arrows, and other military weapons, scholars have posited that their military use was not as extensive as once thought and that these weapons only saw comprehensive service during the Zheng dynasty (932–1358) in the late 13th century. There is an increasingly growing argument that the Tahamaja empire was the first to discover the invention of gunpowder, and its manufacturing methods were brought to Da Huang by their interaction. Another purported argument is that the innovation was concurrent, and both the ancient Jin and Tahamaja developed gunpowder simultaneously around the same time.}}}}. However, by the late 6th century CE, centuries of disunity led to the fall of the Jin. The following [[Zhou dynasty|Zhou]] (581–618) and the [[Later Wei dynasty|Later Wei]] (618–907) dynasties would reunify the empire. The xenophilic Later Wei welcomed foreign trade and culture across the Kayatman Sea and the Jade Road and adapted [[N'nhivara|N'nhivaranism]] to Jin culture. | ||

The [[Song dynasty]] (907–932) would replace the Later Wei and see an increasingly urban and commercialised economy in the empire. During this period, the civilian {{wp|Scholar-official|scholar-officials, or the literati class}}, would emerge and replace the military aristocrats of earlier dynasties with the introduction of the {{wp|Imperial examination|Song Imperial examination system}}. The Song emperors sought to avoid the same mistakes that had led to the downfall of their predecessors and introduce wide-ranging reforms to curb the power of the military. However, in 932, the [[Bayarid Empire|Bayarid invasion]] cut short the Song reforms and established the [[Great Khan's Court in Taizhou]], also known as the | The [[Song dynasty]] (907–932) would replace the Later Wei and see an increasingly urban and commercialised economy in the empire. During this period, the civilian {{wp|Scholar-official|scholar-officials, or the literati class}}, would emerge and replace the military aristocrats of earlier dynasties with the introduction of the {{wp|Imperial examination|Song Imperial examination system}}. The Song emperors sought to avoid the same mistakes that had led to the downfall of their predecessors and introduce wide-ranging reforms to curb the power of the military. However, in 932, the [[Bayarid Empire|Bayarid invasion]] cut short the Song reforms and established the [[Great Khan's Court in Taizhou]], also known as the Zheng dynasty (932–1358), by Jin historians. Another foreign culture would conquer the Bayarid-led Zheng dynasty, the Kra, establishing the [[Anachak Kang|Kra–Na dynasty]] (1358–1674) before the [[Huang dynasty (1674–1902)|Huang dynasty (1674–1902)]] reestablished ethnic Jin control. | ||

The Jin monarchy collapsed in 1902 with the [[Wucheng Heavenly Rebellion]] when the [[Republic of Jin]] (ROJ) replaced the Huang dynasty. In its early years as a republic, the country underwent a period of instability known as the [[Warlord Era]] before mostly reunifying in 1913 under a [[Nationalist government]] with the Huang royalist forces spread thin and contained in the central and northern mountains. With financial and military aid from the [[Latium|Empire of the Latins]], the Republic of Jin recovered from the disastrous [[Cross-Strait War|Cross-Strait war]] before participating in the [[Hanaki War]] in 1927 to conquer their claimed lands. However, the Hanaki War ended in another failure for the Jin. The surrender left a power vacuum in the country, leading to renewed fighting between the scattered remnant armies and a reinvigorated royalist army. The civil war culminated into the [[Corrective Movement]] (1931–1943) and ended with a royalists coup from disaffected republican generals and civil servants who wanted an end to the instability. The Huang emperor was reinstated to the throne, and the military and civil servants reestablished the dynasty on 12 February 1943. | The Jin monarchy collapsed in 1902 with the [[Wucheng Heavenly Rebellion]] when the [[Republic of Jin]] (ROJ) replaced the Huang dynasty. In its early years as a republic, the country underwent a period of instability known as the [[Warlord Era]] before mostly reunifying in 1913 under a [[Nationalist government]] with the Huang royalist forces spread thin and contained in the central and northern mountains. With financial and military aid from the [[Latium|Empire of the Latins]], the Republic of Jin recovered from the disastrous [[Cross-Strait War|Cross-Strait war]] before participating in the [[Hanaki War]] in 1927 to conquer their claimed lands. However, the Hanaki War ended in another failure for the Jin. The surrender left a power vacuum in the country, leading to renewed fighting between the scattered remnant armies and a reinvigorated royalist army. The civil war culminated into the [[Corrective Movement]] (1931–1943) and ended with a royalists coup from disaffected republican generals and civil servants who wanted an end to the instability. The Huang emperor was reinstated to the throne, and the military and civil servants reestablished the dynasty on 12 February 1943. | ||

Da Huang has since periodically alternated between civil, monarchic and military rule. Whilst the {{wp|Emperor|emperor}} has been seen as the {{wp|Son of Heaven}} and an undisputed autocrat of {{wp|Tianxia|all under Heaven}}, this archaic belief in the emperor's divinity has slowly faded away from the new bureaucrats of the late 20th century. Dissent among government officials has led to the stagnation of the empire's recovery leading to foreign economic exploitation and civil unrest between the literati and the military, alongside a resurging Kra rebellion in the northern | Da Huang has since periodically alternated between civil, monarchic and military rule. Whilst the {{wp|Emperor|emperor}} has been seen as the {{wp|Son of Heaven}} and an undisputed autocrat of {{wp|Tianxia|all under Heaven}}, this archaic belief in the emperor's divinity has slowly faded away from the new bureaucrats of the late 20th century. Dissent among government officials has led to the stagnation of the empire's recovery leading to foreign economic exploitation and civil unrest between the literati and the military, alongside a resurging Kra rebellion in the northern territories. To circumnavigate this byzantine bureaucracy, the [[Yingjie emperor]] introduced the [[1991 Jin constitution|1991 constitution]] as a [[Compromise of 1991|compromise]]<!--Reference the Compromise of 1790--> between the three estates, allowing some form of democratic rule to modernise its bureaucracy. | ||

Da Huang is currently governed as a {{wp|Parliamentary system|parlimentary}} {{wp|Constitutional monarchy|constitutional monarchy}}; in practice, however, structural advantages in the constitution due to the compromise in the 1991 constitution have resulted in a complex parliamentary {{wp|Anocracy|anocratic}} {{wp|Semi-constitutional monarchy|semi-constitutional monarchy}} system balanced between the military, the literati, and the monarchist. Da Huang is a {{wp|Middle power|middle power}} in global affairs and ranks moderately on the {{wp|Human Development Index}}. It is also classified as a {{wp|newly industrialised economy}}, with manufacturing, agriculture, and {{wp|Tourism in Thailand|tourism}} as leading sectors. | Da Huang is currently governed as a {{wp|Parliamentary system|parlimentary}} {{wp|Constitutional monarchy|constitutional monarchy}}; in practice, however, structural advantages in the constitution due to the compromise in the 1991 constitution have resulted in a complex parliamentary {{wp|Anocracy|anocratic}} {{wp|Semi-constitutional monarchy|semi-constitutional monarchy}} system balanced between the military, the literati, and the monarchist. Da Huang is a {{wp|Middle power|middle power}} in global affairs and ranks moderately on the {{wp|Human Development Index}}. It is also classified as a {{wp|newly industrialised economy}}, with manufacturing, agriculture, and {{wp|Tourism in Thailand|tourism}} as leading sectors. | ||

| Line 140: | Line 136: | ||

== Etymology == | == Etymology == | ||

{{Main|Names of Da Huang}} | {{Main|Names of Da Huang}} | ||

[[File:CEM-09-Asiae-Nova-Descriptio-China-2510.jpg|thumb| | [[File:CEM-09-Asiae-Nova-Descriptio-China-2510.jpg|thumb|right|upright=0.8|''Jinae'' (today's [[Longxi]]) and the ''[[Daobac]]'' islands on this 1530 map drawn according to the records of famed [[Tyreseia|Tyresene]] ethnographer and medieval author [[Pulau Keramat-Tyreseia relations#History|Ahumm Bōdashtarti]]]] | ||

The name ''Dà Huáng'' (大黄; lit. "Great Yellow") in its national language, Standard | The name ''Dà Huáng'' (大黄; lit. "Great Yellow") in its national language, Standard Jin, has been used by native Jin since the dynasty's foundation. Its origin is generally accepted to be named after the Yellow River though some modern scholars attributed the name directly to the founder of the early Huang dynasty, Huang Junyan. Another accepted argument for the source of the word is that it was adapted from the poem ''Mother River'' (Jin: 母河; pinyin: ''mǔ hé'') authored by the famous 10th-century CE poet [[Wang Wei]]. The old ''{{wp|Jueju}}'' style poetry depicts the Yellow River as the "Mother River" and the "cradle of Jin civilisation": | ||

{| | {| | ||

!class="nowrap"|《母河》 | !class="nowrap"|《母河》 | ||

| Line 161: | Line 157: | ||

While the name Da Huang has been used natively since the 17th century, foreigners did not use this name during this period. The Jin peninsular includes many contemporary and historical appellations in various languages for the Southeast Ochran country. Of the most common, the word "Jinae" has appeared on many foreign maps and records from the [[Ajax|world]]'s western hemisphere. Its origin has been traced through [[Standard Latin language|Latin]], [[Mutul|Mutli]], and [[Tyreseia|Tyreseian]] back to the {{wp|Old Javanese|Uthire}} word ''Jindā'', used in the [[Tahamaja Empire|Tahamaja empire]]. "Jinae" appears in [[Akutze Selenecha]]'s 1516 translation of the 1346 journal of the Tyresene explorer [[Pulau Keramat-Tyreseia relations#History|Ahumm Bōdashtarti]]. Bōdashtarti's usage was derived from the [[Sydalene language|Scipio-Latinic]] word ''Jiña'', which was in turn derived from Uthire ''Jindā'' (जिन्दा). Jindā was first used in early [[N'nhivara]] scripture, including the Tuntutan Roh (805 BCE) and the Tuntutan Kuasa (850 BCE). In 1655, Clímaco Casados suggested that the word Jinae is derived ultimately from the name of the Jin dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Although usage in Tahamaja sources precedes this dynasty, various sources still give this derivation. According to the ''Latin Dictionary'', the origin of the Uthire word is a matter of debate. | While the name Da Huang has been used natively since the 17th century, foreigners did not use this name during this period. The Jin peninsular includes many contemporary and historical appellations in various languages for the Southeast Ochran country. Of the most common, the word "Jinae" has appeared on many foreign maps and records from the [[Ajax|world]]'s western hemisphere. Its origin has been traced through [[Standard Latin language|Latin]], [[Mutul|Mutli]], and [[Tyreseia|Tyreseian]] back to the {{wp|Old Javanese|Uthire}} word ''Jindā'', used in the [[Tahamaja Empire|Tahamaja empire]]. "Jinae" appears in [[Akutze Selenecha]]'s 1516 translation of the 1346 journal of the Tyresene explorer [[Pulau Keramat-Tyreseia relations#History|Ahumm Bōdashtarti]]. Bōdashtarti's usage was derived from the [[Sydalene language|Scipio-Latinic]] word ''Jiña'', which was in turn derived from Uthire ''Jindā'' (जिन्दा). Jindā was first used in early [[N'nhivara]] scripture, including the Tuntutan Roh (805 BCE) and the Tuntutan Kuasa (850 BCE). In 1655, Clímaco Casados suggested that the word Jinae is derived ultimately from the name of the Jin dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Although usage in Tahamaja sources precedes this dynasty, various sources still give this derivation. According to the ''Latin Dictionary'', the origin of the Uthire word is a matter of debate. | ||

Da Huang is also sometimes referred to by its informal name "Zhongguo" ([[Simplified Jin characters|simplified Jin]]: 中国; [[Traditional Jin characters|traditional Jin]]: 中國; {{wp|Pinyin|pinyin}}: ''Zhōngguó'') from ''zhōng'' ("central") and ''guó'' ("state"), a term developed under the [[Eastern Liao]] dynasty in reference to its {{wp|Demesne|royal demesne}}. The name ''Zhongguo'' is also translated to "Middle Kingdom" in [[Standard Latin language|Latin]] and was used as a cultural concept to distinguish the [[Jinxia]] people from [[Jin-Yi distinction|perceived "barbarians"]]. It was then applied to the area around [[Qinjing]] (present-day Daxing) during the [[Western Liao]] dynasty and then to the [[Central Jin Plain]] before being used as an occasional synonym for the state under the [[ | Da Huang is also sometimes referred to by its informal name "Zhongguo" ([[Simplified Jin characters|simplified Jin]]: 中国; [[Traditional Jin characters|traditional Jin]]: 中國; {{wp|Pinyin|pinyin}}: ''Zhōngguó'') from ''zhōng'' ("central") and ''guó'' ("state"), a term developed under the [[Eastern Liao]] dynasty in reference to its {{wp|Demesne|royal demesne}}. The name ''Zhongguo'' is also translated to "Middle Kingdom" in [[Standard Latin language|Latin]] and was used as a cultural concept to distinguish the [[Jinxia]] people from [[Jin-Yi distinction|perceived "barbarians"]]. It was then applied to the area around [[Qinjing]] (present-day Daxing) during the [[Western Liao]] dynasty and then to the [[Central Jin Plain]] before being used as an occasional synonym for the state under the [[Zheng dynasty (Ajax)|Zheng dynasty]] (also known as the [[Great Khan's Court in Taizhou]]). | ||

== History == | == History == | ||

{{main|History of Da Huang}} | {{main|History of Da Huang}} | ||

:''For a chronological guide, see [[Timeline of | :''For a chronological guide, see [[Timeline of Jinae history]]'' | ||

=== Prehistory === | === Prehistory === | ||

{{Further|History of Da Huang#Prehistory}} | |||

[[File:National Museum of China 2014.02.01 14-43-38.jpg|thumb|right|upright=0.8|10,000 years old pottery, {{wp|Xianren Cave}} culture (18000–7000 BCE)]] | [[File:National Museum of China 2014.02.01 14-43-38.jpg|thumb|right|upright=0.8|10,000 years old pottery, {{wp|Xianren Cave}} culture (18000–7000 BCE)]] | ||

Regarded as one of the [[Ajax|world]]'s oldest civilisation, Da Huang is home to multiple archaeological and human-fossil sites dating from 680,000–780,000 years ago. {{wp|Archaeological excavation|Archaeological expeditions}} by the Daxing Academy have found various early human fossils, such as the {{wp|Yuanmou Man|Northern Snowman}} in [[Beixuefeng]], the oldest fossil evidence of humans in Jinae, and the fossils of the {{wp|Peking Man|Xian Man}}, a ''{{wp|Homo erectus}}'' who used fire, discovered in the {{wp|Xiaren cave|Xianren Cave}} home to the oldest continuously inhabited human sites up until the late 4th millennium BCE. The fossilised teeth of ''{{wp|Homo sapiens}}'', dating to 125,000–80,000 years ago, have also been discovered in [[Longdong Cave]], [[Shannan]]. Humans likely already settled in Da Huang at the earliest 2.12 million years ago, evidenced by stone tools recovered from the {{wp|Loess Plateau}} in northwestern Jinae. | Regarded as one of the [[Ajax|world]]'s oldest civilisation, Da Huang is home to multiple archaeological and human-fossil sites dating from 680,000–780,000 years ago. {{wp|Archaeological excavation|Archaeological expeditions}} by the Daxing Academy have found various early human fossils, such as the {{wp|Yuanmou Man|Northern Snowman}} in [[Beixuefeng]], the oldest fossil evidence of humans in Jinae, and the fossils of the {{wp|Peking Man|Xian Man}}, a ''{{wp|Homo erectus}}'' who used fire, discovered in the {{wp|Xiaren cave|Xianren Cave}} home to the oldest continuously inhabited human sites up until the late 4th millennium BCE. The fossilised teeth of ''{{wp|Homo sapiens}}'', dating to 125,000–80,000 years ago, have also been discovered in [[Longdong Cave]], [[Shannan]]. Humans likely already settled in Da Huang at the earliest 2.12 million years ago, evidenced by stone tools recovered from the {{wp|Loess Plateau}} in northwestern Jinae. | ||

| Line 176: | Line 173: | ||

{{Further|Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors|Wei dynasty|Zhang dynasty|Liao dynasty|Spring and Autumn period|Warring States period}} | {{Further|Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors|Wei dynasty|Zhang dynasty|Liao dynasty|Spring and Autumn period|Warring States period}} | ||

[[File:甲骨文发现地 - panoramio.jpg|thumb|upright=0.8|right|[[Yinxu]], the ruins of the capital of the late [[Zhang dynasty]] (14th century BCE)]] | [[File:甲骨文发现地 - panoramio.jpg|thumb|upright=0.8|right|[[Yinxu]], the ruins of the capital of the late [[Zhang dynasty]] (14th century BCE)]] | ||

There are multiple competing records of which dynasty was the first to rule in Jinae, though the earliest records point to the semi-legendary Kingdom of Wei (also known as the Wei dynasty). If these records were to be believed, the Wei dynasty ruled in Central Jinae around 2070 BCE. It would have begun Da Huang's political system based on hereditary monarchies, or dynasties, which practice lasted to the modern day. However, the Wei dynasty is considered mythical as historians have yet to prove if the Bronze Age excavation sites at | There are multiple competing records of which dynasty was the first to rule in Jinae, though the earliest records point to the semi-legendary Kingdom of Wei (also known as the Wei dynasty). If these records were to be believed, the Wei dynasty ruled in Central Jinae around 2070 BCE. It would have begun Da Huang's political system based on hereditary monarchies, or dynasties, which practice lasted to the modern day. However, the Wei dynasty is considered mythical as historians have yet to prove if the Bronze Age excavation sites at '''-insert name here-''' are the remains of the Wei dynasty or another culture from the same period. | ||

In contrast, contemporary historians and archaeological evidence confirm the succeeding Zhang dynasty as the earliest dynasty to have ruled Central Jinae. Founded by Tang of Zhang (Cheng Zhang), the Zhang ruled the fertile floodplains around the Yellow River in Central Jinae from the 17th to the | In contrast, contemporary historians and archaeological evidence confirm the succeeding Zhang dynasty as the earliest dynasty to have ruled Central Jinae. Founded by Tang of Zhang (Cheng Zhang), the Zhang ruled the fertile floodplains around the Yellow River in Central Jinae from the 17th to the 11th century BCE, traditionally succeeding the Wei dynasty—their oracle bone script (from c.1500 BCE) represents the oldest form of Jin writing yet found and is a direct ancestor of modern Jin characters. Excavations at the Ruins of Yinxu (near modern-day Yin), which has been identified as the last Zhang capital, uncovered eleven major royal tombs and the foundations of palaces and ritual sites containing weapons of war and remains of animal and human sacrifices. Tens of thousands of bronze, jade, stone, bone, and ceramic artefacts have been found on the site. | ||

The Zhang eventually declined due to various factors, including internal conflicts, external invasions, and changes in climate and agriculture. They were eventually conquered by the Liao, who ruled between the 11th and 5th centuries BCE. | The Zhang eventually declined due to various factors, including internal conflicts, external invasions, and changes in climate and agriculture. They were eventually conquered by the Liao, who ruled between the 11th and 5th centuries BCE. | ||

| Line 186: | Line 183: | ||

===Imperial Jinae=== | ===Imperial Jinae=== | ||

{{Further||Wu dynasty|Jin dynasty|Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period|Zhou dynasty|Later Wei|Three Kingdoms period|Song dynasty}} | |||

[[File:Army of Terracotta.jpg|thumb|upright=0.8|right|Da Huang's first emperor, [[Wu Shi Huang]], is famed for having united Jinae proper and ordering the construction of several marvel feats of engineering; this includes the lifelike [[terracotta]] soldier statues from the [[Terracotta Army]], which was meant to guard the [[Mausoleum of the First Wu Emperor]], to uniting the Warring States' walls to form the [[Great Wall of Jinae]].{{efn|Most of the present structure of the Great Wall of Jinae is dated to the time of the Zheng dynasty.}}]] | [[File:Army of Terracotta.jpg|thumb|upright=0.8|right|Da Huang's first emperor, [[Wu Shi Huang]], is famed for having united Jinae proper and ordering the construction of several marvel feats of engineering; this includes the lifelike [[terracotta]] soldier statues from the [[Terracotta Army]], which was meant to guard the [[Mausoleum of the First Wu Emperor]], to uniting the Warring States' walls to form the [[Great Wall of Jinae]].{{efn|Most of the present structure of the Great Wall of Jinae is dated to the time of the Zheng dynasty.}}]] | ||

The Warring States period ended in 221 BCE after the state of Wu conquered the other six kingdoms and reunited the former territories of the Liao dynasty, establishing the dominant order of autocracy under the Wu state. King Zheng of Wu proclaimed himself the First Emperor of the Wu dynasty as Wu Shi Huang (Jin: 吳始皇; pinyin: ''Wú Shǐ Huáng'') and enacted Wu's legalist reforms throughout Jinae. Most notable of his reforms was the standardisation of Jin characters, measurements, road widths (i.e., cart axles' length), currency, and the introduction of the ''jùnxiàn'' system (郡縣制, "commandery-county system") or prefectural system, with the establishment of twenty-two prefectures and a rotational system for appointing local officials {{efn|The ''jùnxiàn'' system gave more power to the central government as compared to the traditional ''fēngjiàn'' system ( | The Warring States period ended in 221 BCE after the state of Wu conquered the other six kingdoms and reunited the former territories of the Liao dynasty, establishing the dominant order of autocracy under the Wu state. King Zheng of Wu proclaimed himself the First Emperor of the Wu dynasty as Wu Shi Huang (Jin: 吳始皇; pinyin: ''Wú Shǐ Huáng'') and enacted Wu's legalist reforms throughout Jinae. Most notable of his reforms was the standardisation of Jin characters, measurements, road widths (i.e., cart axles' length), currency, and the introduction of the ''jùnxiàn'' system (郡縣制, "commandery-county system") or prefectural system, with the establishment of twenty-two prefectures and a rotational system for appointing local officials {{efn|The ''jùnxiàn'' system gave more power to the central government as compared to the traditional ''fēngjiàn'' system (Jin: 封建; lit. 'demarcation and establishment') of the Liao dynasty since it consolidated power at the political centre or the top of the empire's political hierarchy. Modern historians coin this term as a form of a "proto-bureaucratic" system in which power was taken away from the traditional feudal nobility and placed into the hands of the meritocratically appointed state officials whose position is strictly non-hereditary.}}. His dynasty also conquered the Yue tribes in the present-day Guangxi Circuit (Jin: 广西道; pinyin: '''Guǎngxī dào'') and the southern [[Ba state]] {{efn|It was purported that in the late 3rd century BCE, a semi-legendary sagely prince from Ba, Gaozi, would, after his kingdom's conquest, lead the Ba people to the southern islands and found the Kingdom of Nanba. According to the ''[[Book of Jin]]'' (1st century CE), ''Gaozi'' brought agriculture, sericulture, and many other facets of Jin civilisation to the Daoan islands, giving [[Daobac#Early History|ancient Daobac]] its high culture—and presumably, standing as a legitimate civilisation. ''Gaozi'' would also come to represent the authenticating presence of Jin civilisation in Daobac, a claim that the Jin used to justify their sovereignty over Daobac throughout Jinae–Daoan history. However, following the end of the Cross-Strait War and the Hanaki War, Daoan scholars would challenge the authenticity of this account in the late 20th century. Due to contradicting historical and archaeological evidence, Daobac no longer officially recognises ''Gaozi'' and his supposed accomplishments, making Da Huang the only nation still supporting this claim.{{Bulleted list|'''OOC''': To be further discussed with @Pixy (Daobac) regarding name of the prince, the kingdom/state's name, and other details. Currently based of {{wp|Jizi}} and {{wp|History of Korea#Ancient Korea|Ancient Korea}}; with a little inspiration from the {{wp|Yayoi people}}.}}}}, expanding the empire's borders to Jinae proper (present-day Da Huang borders). Wu Shi Huang ordered their ancient capital to be razed, and a new city would build on its ruins. This city would later be known as [[Basingse]] and would become the Zheng dynasty's capital city, retaining its status to the present day. | ||

The Wu dynasty lasted only fifteen years, falling soon after the First Emperor's death. His harsh legalist reforms and policies and his purge of the old aristocracy from the conquered states led to widespread resentment from the peasants and the surviving nobility. This resentment would eventually cumulate into a widespread peasant rebellion after the First Emperor's death, allowing the surviving nobility to reclaim their ancestral estates and military power from their old territories, further developing the unrest into a civil war. | The Wu dynasty lasted only fifteen years, falling soon after the First Emperor's death. His harsh legalist reforms and policies and his purge of the old aristocracy from the conquered states led to widespread resentment from the peasants and the surviving nobility. This resentment would eventually cumulate into a widespread peasant rebellion after the First Emperor's death, allowing the surviving nobility to reclaim their ancestral estates and military power from their old territories, further developing the unrest into a civil war. | ||

The civil war would culminate in the Chu–Jin contention, during which the imperial library at Xiangyang (present-day Danyang) was burned. The Jin dynasty would emerge victorious and rule Jinae proper from 206 BCE to 220 CE, creating a cultural identity amongst its populace still remembered in the ethnonym of the Jin people. The Jin expanded the empire's territory considerably, with their military campaigns defining the borders of the present-day East Ochran cultural sphere on the Ochran mainland. Jin expansion reached as far as the Great Northern Steppes, Seonko | The civil war would culminate in the Chu–Jin contention, during which the imperial library at Xiangyang (present-day Danyang) was burned to the ground. The Jin dynasty would emerge victorious and rule Jinae proper from 206 BCE to 220 CE, creating a cultural identity amongst its populace still remembered in the ethnonym of the Jin people. The Jin expanded the empire's territory considerably, with their military campaigns defining the borders of the present-day East Ochran cultural sphere on the Ochran mainland. Jin expansion and influence reached as far as the Great Northern Steppes, Seonko, the East–South Ochran divide along the Kra Maena river, and the borders of the Tsurushima southern Kitagan peninsula. Jin's involvement in Central Ochran and Lan Na helped establish the land route of the Jade Road and helped develop various Jin-influenced city-states along the route. Jin Jinae gradually became the largest economy of the ancient world. Despite the Jin's initial decentralisation and official abandonment of the Wu philosophy of Legalism in favour of Ruism, Wu's legalist institutions and policies continued to be employed by the Jin government and its successors. | ||

===Two Conquest Dynasties=== | ===Two Conquest Dynasties=== | ||

{{Main|Conquest dynasties}} | |||

{{Further|Bayarid conquest of Jinae|Zheng dynasty|Division of the Bayarid Empire|War of the Bayarid's Successors|Zheng—Tahamaja contention|Fall of the Zheng dynasty|Siriwang Eruption|Upheaval of the Western Barbarians|Long March|Anachak Kang}} | |||

{{See also|Seven Centuries of Humiliation}} | |||

===Five Pecks of Rice Rebellion and the return of ethnic Jin rule=== | ===Five Pecks of Rice Rebellion and the return of ethnic Jin rule=== | ||

{{Main|Huang dynasty (1674–1902)}} | |||

{{Further|Five Pecks of Rice Rebellion}} | |||

===Cross-strait War and the Fall of the Huang dynasty=== | ===Cross-strait War and the Fall of the Huang dynasty=== | ||

{{Further|Sick man of Ochran|Late Huang reforms|Cross-Strait War|Wucheng Heavenly Rebellion}} | |||

===Establishment of the Republic and the Hanaki War=== | ===Establishment of the Republic and the Hanaki War=== | ||

{{Main|Republic of Jin}} | |||

{{Further|Warlord Era|Hanaki War|Second Cross-Strait War}} | |||

===The Corrective Movement and Reestablishment of the Huang dynasty=== | ===The Corrective Movement and Reestablishment of the Huang dynasty=== | ||

{{Further|Corrective Movement}} | |||

===Reforms and contemporary history=== | ===Reforms and contemporary history=== | ||

{{Further|Self-Strengthening Movement|Monsoon War|Gengzi New Policies|Hundred Days' Reform|1991 Jin constitution|}} | |||

== Geography == | == Geography == | ||

| Line 214: | Line 222: | ||

{{Main|Environment of Da Huang|Environmental issues in Da Huang}} | {{Main|Environment of Da Huang|Environmental issues in Da Huang}} | ||

{{See also|Renewable energy in Da Huang|Water resources of Da Huang|Energy policy of Da Huang|Climate change in Da Huang}} | {{See also|Renewable energy in Da Huang|Water resources of Da Huang|Energy policy of Da Huang|Climate change in Da Huang}} | ||

===Political geography === | |||

{{Main|Borders of Da Huang|Coastline of Da Huang|Territorial changes of the Jin}} | |||

[[File:Jinae Administrative.png|thumb|Map showing the territorial claims of Da Huang]] | |||

== Politics == | == Politics == | ||

{{Main|Politics of Da Huang}}{{Further|1991 | {{Main|Politics of Da Huang}}{{Further|1991 Jin constitution}} | ||

=== Political triumvirate === | === Political triumvirate === | ||

{{Further|Royalist Party|Constitutionalist Party|EAGF under Cao Fang}}{{See also|Republican Revolutionarists in Da Huang}} | {{Further|Royalist Party|Constitutionalist Party|EAGF under Cao Fang}}{{See also|Republican Revolutionarists in Da Huang}} | ||

| Line 224: | Line 235: | ||

=== Administrative divisions === | === Administrative divisions === | ||

{{Main|Administrative divisions of Da Huang}} | {{Main|Administrative divisions of Da Huang}} | ||

Da Huang is constitutionally a {{wp|unitary state}} divided into nineteen [[Circuits of Jinae|circuits]], three [[Autonomous regions of Da Huang|autonomous regions]]{{efn|The Beiyue and Shanbei Autonomous regions was designated for the [[Kra People|Kra (Zhuang)]] from the beginning of the [[Huang dynasty (1674–1902)|early Huang dynasty]] with the implementation of the 传播文明之根的政策 (pinyin: ''Chuánbò wénmíng zhī gēn de zhèngcè''; Policy to spread the roots of civilisation). The policy was later expanded under the [[Republic of Jin]] to include other minority ethnic groups and religious communities that refuse to convert or assimilate and accept the Jin way of life. One such group was the staunchly religious [[Azdarin|Azdarists]] [[Wenmo people|Wenmo]] who were forcefully relocated to the Shaannan Autonomous region.}}, and sixteen [[Directly administered province|direct-administered province]]—collectively referred to as "Southern Jinae"—as well as the [[Special administrative region of Da Huang|special administrative region]] (SAR) of [[Yangcheng]]. Geographically, all 38 administrative divisions of Southern Jinae can be grouped into six regions: [[North Da Huang]], [[Northeastern Da Huang]], [[Northwestern Da Huang]], [[South Central Da Huang]], [[Southeastern Da Huang]], and [[Southwestern Da Huang]]. | |||

Da Huang also has six claimed territories. Many of these territorial disputes are carried over from historical claims, going as far as back as the Jin dynasty.{{efn|While Da Huang currently no longer actively externally claims the territories of [[Daobac]], [[Tsurushima]], and [[Seonko]], which it does not control, as its disputed ''lost provinces'', the regions are still marked as part of the nation's Great Jinae administrative zones in internal politics and education. See [[Territorial disputes of the Jin]] for more details.}} | |||

{{Da Huang provinces big imagemap alt}} | |||

{{Da Huang provinces small imagemap/province list}} | |||

=== Foreign relations === | === Foreign relations === | ||

{{Main|Foreign relations of Da Huang}} | {{Main|Foreign relations of Da Huang}} | ||

| Line 241: | Line 258: | ||

{{Main|Everlasting Army|Paramilitary forces of Da Huang}} | {{Main|Everlasting Army|Paramilitary forces of Da Huang}} | ||

{{See also|Cao Fang|EAGF under Cao Fang}} | {{See also|Cao Fang|EAGF under Cao Fang}} | ||

[[File:J-94 4th Generation | [[File:J-94 4th Generation Fighter.jpeg|thumb|[[Anxi J-94]] {{wp|Fourth-generation jet fighter|4th generation}} fighter used by the [[Everlasting Army Air Force|EAAF]]]] | ||

The Everlasting Army ([[Simplified Jin characters|Jin]]: 永恒軍; {{wp|Pinyin|pinyin}}: ''Yǒnghéngjūn''), more fully called the Standing Army of the Central Plains, (中原帝國常備軍; ''Zhōngyuán dìguó chángbèijūn'') constitutes the military of Da Huang and is amongst the [[Ajax|world's]] largest militaries. It consists of the [[Everlasting Army Ground Force|Ground Force]] (EAGF), the [[Everlasting Army Navy|Navy]] (EAN), the [[Everlasting Army Air Force|Air Force]] (EAAF), and various {{wp|Paramilitary|paramilitary}} forces that serve as the {{wp|Gendarmerie|gendarmerie}} during peacetime. | The Everlasting Army ([[Simplified Jin characters|Jin]]: 永恒軍; {{wp|Pinyin|pinyin}}: ''Yǒnghéngjūn''), more fully called the Standing Army of the Central Plains, (中原帝國常備軍; ''Zhōngyuán dìguó chángbèijūn'') constitutes the military of Da Huang and is amongst the [[Ajax|world's]] largest militaries. It consists of the [[Everlasting Army Ground Force|Ground Force]] (EAGF), the [[Everlasting Army Navy|Navy]] (EAN), the [[Everlasting Army Air Force|Air Force]] (EAAF), and various {{wp|Paramilitary|paramilitary}} forces that serve as the {{wp|Gendarmerie|gendarmerie}} during peacetime. | ||

| Line 248: | Line 265: | ||

According to the constitution, serving in the armed forces is the duty of all Jin citizens. Da Huang still uses the active draft system for males over the age of 18, except those with a criminal record or who can prove that their loss would bring hardship to their families. Males who have not completed their pre-university education, are awarded the Public Service Commission (PSC) scholarship, or are pursuing a medical degree can opt to defer their draft. However, this deferment is subject to varying degrees of success; well-to-do citizens have been known to bribe draft officials, most notably from the EAGF, to dodge the draft entirely. Hence, the poor and less educated are often subjected to varying lengths of active service, with some serving for as long as the maximum five years of reserve training as a Territorial Defence Soldier. This practice has long been criticised, as some media question its efficacy and value. It is alleged that conscripts of the EAGF end up as servants to senior officers or clerks in military cooperative shops. In a report issued in April 2019, EAGF military conscripts are found to have faced institutionalised abuse systematically hushed up by the army authorities. | According to the constitution, serving in the armed forces is the duty of all Jin citizens. Da Huang still uses the active draft system for males over the age of 18, except those with a criminal record or who can prove that their loss would bring hardship to their families. Males who have not completed their pre-university education, are awarded the Public Service Commission (PSC) scholarship, or are pursuing a medical degree can opt to defer their draft. However, this deferment is subject to varying degrees of success; well-to-do citizens have been known to bribe draft officials, most notably from the EAGF, to dodge the draft entirely. Hence, the poor and less educated are often subjected to varying lengths of active service, with some serving for as long as the maximum five years of reserve training as a Territorial Defence Soldier. This practice has long been criticised, as some media question its efficacy and value. It is alleged that conscripts of the EAGF end up as servants to senior officers or clerks in military cooperative shops. In a report issued in April 2019, EAGF military conscripts are found to have faced institutionalised abuse systematically hushed up by the army authorities. | ||

Historically, Da Huang's military has been mired in corruption and nepotism; the | Historically, Da Huang's military has been mired in corruption and nepotism; the Eastern Depot of the EAGF functions as the political arm of the EAGF military authorities. It has overlapping social and political tasks with civilian bureaucracy, adopting an anti-democratic ideology recently. The military is also notorious for numerous corruption incidents, such as accusations of illegal trafficking, promotion of high-ranking officers in the form of nepotism, and deeply entrenching themselves into the Jin civilian politics. | ||

== Economy == | == Economy == | ||

{{Main|Economy of Da Huang}}{{For| | {{Main|Economy of Da Huang}}{{For|the economic history of Jinae|Economic history of Jinae before 1902|Economic history of Jinae (1902–1943)|Economic history of Jinae (1943–present)}} | ||

=== Recent econmic history === | === Recent econmic history === | ||

=== Income and wealth disparities === | === Income and wealth disparities === | ||

| Line 257: | Line 274: | ||

=== Exports and manufacturing === | === Exports and manufacturing === | ||

=== Tourism === | === Tourism === | ||

{{Further|Tourism in Da Huang}} | {{Further|Tourism in Da Huang}}{{See also|Jin World Heritage Site}} | ||

=== Agriculture and natural resources === | === Agriculture and natural resources === | ||

{{Further|Agriculture in Da Huang}} | {{Further|Agriculture in Da Huang}} | ||

| Line 295: | Line 313: | ||

== Culture and Society== | == Culture and Society== | ||

{{Main|Jin culture}} | {{Main|Jin culture}} | ||

{{wide image|Temple of Heaven, Beijing, China - 010 edit.jpg|1650px|The [[Temple of Heaven]], a center of [[Jin theology|heaven worship]] and a [[Jin World Heritage Site|designated World Heritage site]], symbolizes the Interactions Between Heaven and Mankind}} | |||

{{wide image|Temple of Heaven, Beijing, China - 010 edit.jpg|1650px|The [[Temple of Heaven]], a center of [[Jin theology|heaven worship]] and a [[Jin World Heritage Site|designated World Heritage site]], symbolizes the Interactions Between Heaven and Mankind | [[File:Jiangnan03.jpg|thumb|right|upright=0.8|The [[Fenghuang Examination Hall]], the largest examination hall for imperial examination in ancient Jinae]] | ||

Since ancient times, Jin culture has been heavily influenced by the Hundred Schools of Thought philosophies from the 8-5th century BCE. Of the most prominent, ''Fajia'' (Legalism) and ''Rujia'' (Ruism) contended to become the state's enforced philosophy for much of the country's early dynastic era, so much so that the line between philosophy and religion blurred, and one could no longer distinguish between the two. Promoting the two schools of thought provided opportunities for social advancement; one's high performance in the prestigious imperial examinations would allow one to promote their social class and improve their socioeconomic standing. The imperial examinations are thought to have originated from the time of the Jin dynasty. The literary emphasis of the exams affected the general perception of cultural refinement in Da Huang, such as the belief that calligraphy, poetry, and painting were higher forms of art than dancing or drama. This emphasis, in turn, transformed Jin culture into an inward-looking one focusing on the nation's cultural history and national perspective of the world. Today, examinations and a culture of merit remain greatly valued by the general populace, but their practice has been questioned and challenged by the political instability between the triumvirate. | |||

=== Architecture === | === Architecture === | ||

{{Main|Jin architecture|List of Designated Heritage Sites in Da Huang}} | {{Main|Jin architecture|List of Designated Heritage Sites in Da Huang}} | ||

[[File:Fenghuang old town.JPG|thumb|right|upright=0.8|[[Fenghuang County]], an ancient town that harbors many architectural remains of the Later Wei and Song dynasty, including the [[Fenghuang Examination Hall]]]] | |||

=== Literature === | === Literature === | ||

{{Main|Jin literature}} | {{Main|Jin literature}} | ||

| Line 310: | Line 331: | ||

{{Main|Jin clothing|Jinfu}} | {{Main|Jin clothing|Jinfu}} | ||

=== Sports === | === Sports === | ||

{{ | {{See also|Sports in Da Huang|Cuju in Da Huang}} | ||

[[File:10th_all_china_games_Jian_pair_406_cropped.jpg|thumb|right|upright=0.8|A jian competition at the 163rd Tianxiawudi Jianshu Liansai]] | |||

Da Huang has some of the world's oldest sporting cultures. There is evidence that archery (射箭; ''shèjiàn''), pitch-pot (投壶; ''tóuhú'') and swordplay (劍術; ''jiànshù'') were practised as far back as the Zhang dynasty (17th to the 11th century BCE). ''Cuju'', a ball sport loosely related to modern association football (claimed by Jin authorities and some historians as the sport's origin), dates back to the Jin dynasty (206 BCE to 220 CE). Traditional Jin martial arts, such as ''qigong'' and ''taiji boxing'', have been widely practised by the inhabitants of Jinae outside of the military since the formation of the Hundred Schools of Thought (8th-5th century BCE) as well. Due to the emphasis on physical fitness in Jin culture, a "proto-professional sports" culture has become a mainstay in popular Jin sports throughout its history, which later transitioned to a fully professional model with the introduction of modern sports, largely under the influence of foreign influence and Jin reformers. The [[Tianxiawudi Jianshu Liansai]] (or the Unrivaled under Heaven Swordsmanship League), officially founded by the Jin emperor in 103 CE, is one of the world's oldest and longest-continuing professional sports leagues. | |||

Traditional sports in ancient Jinae are vibrant and diversified, each with its own distinct features. Owing to the isolationist stance of the Jin during the early Huang dynasty, most of these sports are still held in high regard and practised today. They can be classified into three groups: Performing and entertaining sports, activities for physical fitness, and traditional martial arts. Jin martial arts, in particular, such as qigong and taiji, are still taught as part of the compulsory primary and secondary school curriculum. Amongst the myriad of traditional jin sports, dragon boat racing, Zheng-style wrestling, and horse racing remain the most popular in modern-day Da Huang. Throughout its history, organised violence between rival dragon boat racing factions has not been uncommon, and the violence from the spectators of the sport has resulted in periodic bans that have resulted in the sport's waning popularity in recent times. | |||

Outside of the traditional sports, cuju (蹴鞠; ''cùjū''; "kick ball"; Jin word for association football, not to be confused with the similar and traditional cuju ball game) is the most popular spectator sport in Da Huang. The Cuju Association of Jinae have an immense national following amongst the Jin populace, with well-known national household names such as [[Guo Junyi]] (郭俊谊; ''guō jùnyì'') and [[Shi Jiayi]] (施佳懿; ''shī jiāyì'') being held in high esteem. Da Huang's professional cuju league, known as [[Jin Jia Liansai]] (or Jinae League One), is among one of the largest association football markets in East Ochran. Other popular modern sports include table tennis, badminton, and swimming. | |||

Motorsport has enjoyed increasing popularity in Da Huang in recent years, with Jin automotive manufacturers having found some success in the [[Formula Elite (Ajax)|Formula Elite]]. | |||

== See also == | == See also == | ||

| Line 319: | Line 348: | ||

{{Notelist|1}} | {{Notelist|1}} | ||

{{Jinae topics}} | |||

{{Navboxes | |||

|title = Articles related to Ajax | |||

|list = | |||

{{Ajax info pages}} | {{Ajax info pages}} | ||

{{Template:Sovereign states and dependent territories (Ajax)|state=collapsed}} | |||

}} | |||

Latest revision as of 17:09, 27 February 2024

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Great Huang | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: 永恒軍軍歌 Yǒnghéngjūn jūngē "Anthem of the Everlasting Army" | |

Territory controlled by the Huang dynasty is shown in dark green; territory claimed but not controlled is shown in light green. | |

Political Map of Da Huang circa 1930 | |

| Capital | Basingse |

| Largest city | Suicheng |

| Official languages | Standard Jin |

| Recognised regional languages | |

| Official script | Simplified Jin |

| Ethnic groups (2022) | |

| Religion (2022) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Jin |

| Government | Unitary parlimentary anocratic semi-consitutional monarchy |

• Emperor | Yingjie Emperor |

• Prince Regent | Shunwang, Prince Huang |

• Prime Minister | Cheng Pu |

| Legislature | Advisory Council |

| Formation | |

• First pre-imperial dynasty | c. 2070 BCE |

• First Imperial dynasty | c. 221 BCE |

• Conquest by the Bayarids | 932 CE |

• Establishment of the Great Khan's Court-in-Taizhou | 1145 CE |

• Great Kra Invasion | 1353—1358 |

• Establishment of the Kra—Na dynasty | 1358 |

• Five Pecks of Rice Rebellion | 1672—1674 |

• Establishment of the ethnic Jin—Huang dynasty | 1674 |

• Wucheng Heavenly Rebellion | 1900—1902 |

• Republic of Jin established | 1902—1931 |

• Corrective Movement | 1931—1943 |

• End of the Republic and Reestablishment of the Huang dynasty | 12 February 1943 |

• Current constitution (1991) | 29 August 1991 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,125,344 km2 (434,498 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | 121,648,117 |

• Density | 108.1/km2 (280.0/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | $1.387 trillion |

• Per capita | $11,400 |

| Gini (2022) | 36.4 medium |

| HDI (2022) | high |

| Currency | Yuan (元/¥) (JY) |

| Time zone | (GST+8) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+7 ((GST+7)) |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy CE |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +16 |

| Internet TLD | .jn |

The Huang dynasty, officially the Great Huang (Jin: 大黄; pinyin: Dà Huáng), is a sovereign state in Southeast Ochran, situated in the Jin Peninsula, spanning 1,125,344 square kilometres (434,498 sq mi), with a population of 121,648,117. The country is bordered to the northeast by Seonko and shares maritime borders with Daobac to the south and Tsurushima through the Kaihei islands to the east. The national capital is Basingse, and the most populous city and largest financial centre is Suicheng.

Modern Jin traces their origins to a cradle of civilisation in the fertile Yellow River basin in the Central Jin Plain. Their long occupation, initially in varying forms of hunter-gatherers, emerged into settled life as early as 7000 BCE, gradually evolving into multiple early Jin civilisations. The interactions of different and distinct cultures and ethnic groups influenced each other's development; specific cultural regions that developed the early Jin civilisation were the Huanghe civilisation, the Chiangjiang civilisation, and the Nanbei culture.

These early civilisations would set the foundations of several regional cities, eventually turning into city-states and petty kingdoms. The semi-legendary Kingdom of Wei in the 21st century BCE and the well-attested Zhang and Liao states developed a bureaucratic political system to serve hereditary monarchies known as dynasties. Jin writing, Jin classic literature, and the Hundred Schools of Thought emerged during this period and influenced Da Huang and its neighbours for centuries to come.

Early Jin historians attributed to the notion of one dynasty succeeding another; however, current archaeological, geological, and anthropological findings have shown that the political situation in the Jin peninsula was much more complicated. These political entities existed concurrently and would remain disunited until the third century BCE when the King of Wu, Wu Shi Huang, founded the first Jin empire, the short-lived Wu dynasty. The more stable Jin dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) followed the fall of the Wu and established a model for nearly two millennia in which the Jin empire was one of the world's foremost economic power.

Throughout its existence, the Jin dynasty expanded, fractured, and reunified; was conquered and reestablished; absorbed foreign religions and ideas; and made world-leading scientific advances, such as the Four Great Inventions: gunpowder, paper, the compass, and printing[a]. However, by the late 6th century CE, centuries of disunity led to the fall of the Jin. The following Zhou (581–618) and the Later Wei (618–907) dynasties would reunify the empire. The xenophilic Later Wei welcomed foreign trade and culture across the Kayatman Sea and the Jade Road and adapted N'nhivaranism to Jin culture.

The Song dynasty (907–932) would replace the Later Wei and see an increasingly urban and commercialised economy in the empire. During this period, the civilian scholar-officials, or the literati class, would emerge and replace the military aristocrats of earlier dynasties with the introduction of the Song Imperial examination system. The Song emperors sought to avoid the same mistakes that had led to the downfall of their predecessors and introduce wide-ranging reforms to curb the power of the military. However, in 932, the Bayarid invasion cut short the Song reforms and established the Great Khan's Court in Taizhou, also known as the Zheng dynasty (932–1358), by Jin historians. Another foreign culture would conquer the Bayarid-led Zheng dynasty, the Kra, establishing the Kra–Na dynasty (1358–1674) before the Huang dynasty (1674–1902) reestablished ethnic Jin control.

The Jin monarchy collapsed in 1902 with the Wucheng Heavenly Rebellion when the Republic of Jin (ROJ) replaced the Huang dynasty. In its early years as a republic, the country underwent a period of instability known as the Warlord Era before mostly reunifying in 1913 under a Nationalist government with the Huang royalist forces spread thin and contained in the central and northern mountains. With financial and military aid from the Empire of the Latins, the Republic of Jin recovered from the disastrous Cross-Strait war before participating in the Hanaki War in 1927 to conquer their claimed lands. However, the Hanaki War ended in another failure for the Jin. The surrender left a power vacuum in the country, leading to renewed fighting between the scattered remnant armies and a reinvigorated royalist army. The civil war culminated into the Corrective Movement (1931–1943) and ended with a royalists coup from disaffected republican generals and civil servants who wanted an end to the instability. The Huang emperor was reinstated to the throne, and the military and civil servants reestablished the dynasty on 12 February 1943.

Da Huang has since periodically alternated between civil, monarchic and military rule. Whilst the emperor has been seen as the Son of Heaven and an undisputed autocrat of all under Heaven, this archaic belief in the emperor's divinity has slowly faded away from the new bureaucrats of the late 20th century. Dissent among government officials has led to the stagnation of the empire's recovery leading to foreign economic exploitation and civil unrest between the literati and the military, alongside a resurging Kra rebellion in the northern territories. To circumnavigate this byzantine bureaucracy, the Yingjie emperor introduced the 1991 constitution as a compromise between the three estates, allowing some form of democratic rule to modernise its bureaucracy.

Da Huang is currently governed as a parlimentary constitutional monarchy; in practice, however, structural advantages in the constitution due to the compromise in the 1991 constitution have resulted in a complex parliamentary anocratic semi-constitutional monarchy system balanced between the military, the literati, and the monarchist. Da Huang is a middle power in global affairs and ranks moderately on the Human Development Index. It is also classified as a newly industrialised economy, with manufacturing, agriculture, and tourism as leading sectors.

Etymology

The name Dà Huáng (大黄; lit. "Great Yellow") in its national language, Standard Jin, has been used by native Jin since the dynasty's foundation. Its origin is generally accepted to be named after the Yellow River though some modern scholars attributed the name directly to the founder of the early Huang dynasty, Huang Junyan. Another accepted argument for the source of the word is that it was adapted from the poem Mother River (Jin: 母河; pinyin: mǔ hé) authored by the famous 10th-century CE poet Wang Wei. The old Jueju style poetry depicts the Yellow River as the "Mother River" and the "cradle of Jin civilisation":

| 《母河》 | Mother River |

|---|---|

|

|

While the name Da Huang has been used natively since the 17th century, foreigners did not use this name during this period. The Jin peninsular includes many contemporary and historical appellations in various languages for the Southeast Ochran country. Of the most common, the word "Jinae" has appeared on many foreign maps and records from the world's western hemisphere. Its origin has been traced through Latin, Mutli, and Tyreseian back to the Uthire word Jindā, used in the Tahamaja empire. "Jinae" appears in Akutze Selenecha's 1516 translation of the 1346 journal of the Tyresene explorer Ahumm Bōdashtarti. Bōdashtarti's usage was derived from the Scipio-Latinic word Jiña, which was in turn derived from Uthire Jindā (जिन्दा). Jindā was first used in early N'nhivara scripture, including the Tuntutan Roh (805 BCE) and the Tuntutan Kuasa (850 BCE). In 1655, Clímaco Casados suggested that the word Jinae is derived ultimately from the name of the Jin dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Although usage in Tahamaja sources precedes this dynasty, various sources still give this derivation. According to the Latin Dictionary, the origin of the Uthire word is a matter of debate.

Da Huang is also sometimes referred to by its informal name "Zhongguo" (simplified Jin: 中国; traditional Jin: 中國; pinyin: Zhōngguó) from zhōng ("central") and guó ("state"), a term developed under the Eastern Liao dynasty in reference to its royal demesne. The name Zhongguo is also translated to "Middle Kingdom" in Latin and was used as a cultural concept to distinguish the Jinxia people from perceived "barbarians". It was then applied to the area around Qinjing (present-day Daxing) during the Western Liao dynasty and then to the Central Jin Plain before being used as an occasional synonym for the state under the Zheng dynasty (also known as the Great Khan's Court in Taizhou).

History

- For a chronological guide, see Timeline of Jinae history

Prehistory

Regarded as one of the world's oldest civilisation, Da Huang is home to multiple archaeological and human-fossil sites dating from 680,000–780,000 years ago. Archaeological expeditions by the Daxing Academy have found various early human fossils, such as the Northern Snowman in Beixuefeng, the oldest fossil evidence of humans in Jinae, and the fossils of the Xian Man, a Homo erectus who used fire, discovered in the Xianren Cave home to the oldest continuously inhabited human sites up until the late 4th millennium BCE. The fossilised teeth of Homo sapiens, dating to 125,000–80,000 years ago, have also been discovered in Longdong Cave, Shannan. Humans likely already settled in Da Huang at the earliest 2.12 million years ago, evidenced by stone tools recovered from the Loess Plateau in northwestern Jinae.

The early Jin civilisations were defined by different and distinct cultures and ethnic groups that inhabited the various major rivers of the Jin Peninsular. Widescale agriculture varied at different times in the various regions, developing gradually from the initial domestications of a few grains and animals to the addition of many other species over subsequent millennia. The earliest evidence of cultivated rice, found by the Chiangjiang River, was carbon-dated to 8,000 years ago. They were home to the Chiangjiang civilisation, the oldest of the three noted early Jin cultures from this millennium. Early evidence for millet agriculture was found in the Yellow River, radiocarbon-dated to about 7000 BCE. They were home to Huanghe civilisation and are traditionally believed to be the origins of modern Jin proto-writing. The Jiahu site of the Huanghe civilisation is one of the best-preserved archaeological sites that feature 3,172 cliff carvings dating to 6000–5000 BCE, featuring 8,453 individual characters such as the sun, moon, stars, gods and scenes of hunting and grazing. These proto-writings would also be developed in the later Nanbei culture and the earlier Chiangjiang civilisation, as their interactions would help influence each other and set the foundations for several regional cities, eventually turning into city-states and petty kingdoms.

Early dynastic rule

There are multiple competing records of which dynasty was the first to rule in Jinae, though the earliest records point to the semi-legendary Kingdom of Wei (also known as the Wei dynasty). If these records were to be believed, the Wei dynasty ruled in Central Jinae around 2070 BCE. It would have begun Da Huang's political system based on hereditary monarchies, or dynasties, which practice lasted to the modern day. However, the Wei dynasty is considered mythical as historians have yet to prove if the Bronze Age excavation sites at -insert name here- are the remains of the Wei dynasty or another culture from the same period.

In contrast, contemporary historians and archaeological evidence confirm the succeeding Zhang dynasty as the earliest dynasty to have ruled Central Jinae. Founded by Tang of Zhang (Cheng Zhang), the Zhang ruled the fertile floodplains around the Yellow River in Central Jinae from the 17th to the 11th century BCE, traditionally succeeding the Wei dynasty—their oracle bone script (from c.1500 BCE) represents the oldest form of Jin writing yet found and is a direct ancestor of modern Jin characters. Excavations at the Ruins of Yinxu (near modern-day Yin), which has been identified as the last Zhang capital, uncovered eleven major royal tombs and the foundations of palaces and ritual sites containing weapons of war and remains of animal and human sacrifices. Tens of thousands of bronze, jade, stone, bone, and ceramic artefacts have been found on the site.

The Zhang eventually declined due to various factors, including internal conflicts, external invasions, and changes in climate and agriculture. They were eventually conquered by the Liao, who ruled between the 11th and 5th centuries BCE. One of the most significant achievements of the Liao Dynasty was the development of the "Mandate of Heaven" concept, which held that the ruler's authority was based on the will of heaven, and a ruler's legitimacy was determined by his ability to govern with benevolence and effectiveness. This concept laid the foundation for the Jin belief in the divine right to rule and influenced the political structure and philosophy of subsequent dynasties. The Liao is also known for its advancements in agriculture, including introducing iron tools and new farming techniques, which increased agricultural production and population growth. This period also saw the development of a sophisticated system of writing and record-keeping, with the use of bronze inscriptions, which provided valuable insights into the history and culture of ancient Jinae.

The society in ancient Jinae under the Liao dynasty was feudalistic, with a king as the central authority. However, power was decentralised, and local lords were granted land and authority in exchange for their loyalty and military service. This practice led to the fragmentation and the emergence of powerful regional states and feudal warlords that slowly eroded centralised authority. Some principalities eventually emerged from the weakened Liao, no longer fully obeyed the Liao king, and continually waged war with each other during the 300-year Spring and Autumn period. By the time of the Warring States period of the 5th–3rd centuries BCE, only seven powerful states were left.

Imperial Jinae

The Warring States period ended in 221 BCE after the state of Wu conquered the other six kingdoms and reunited the former territories of the Liao dynasty, establishing the dominant order of autocracy under the Wu state. King Zheng of Wu proclaimed himself the First Emperor of the Wu dynasty as Wu Shi Huang (Jin: 吳始皇; pinyin: Wú Shǐ Huáng) and enacted Wu's legalist reforms throughout Jinae. Most notable of his reforms was the standardisation of Jin characters, measurements, road widths (i.e., cart axles' length), currency, and the introduction of the jùnxiàn system (郡縣制, "commandery-county system") or prefectural system, with the establishment of twenty-two prefectures and a rotational system for appointing local officials [c]. His dynasty also conquered the Yue tribes in the present-day Guangxi Circuit (Jin: 广西道; pinyin: 'Guǎngxī dào) and the southern Ba state [d], expanding the empire's borders to Jinae proper (present-day Da Huang borders). Wu Shi Huang ordered their ancient capital to be razed, and a new city would build on its ruins. This city would later be known as Basingse and would become the Zheng dynasty's capital city, retaining its status to the present day.

The Wu dynasty lasted only fifteen years, falling soon after the First Emperor's death. His harsh legalist reforms and policies and his purge of the old aristocracy from the conquered states led to widespread resentment from the peasants and the surviving nobility. This resentment would eventually cumulate into a widespread peasant rebellion after the First Emperor's death, allowing the surviving nobility to reclaim their ancestral estates and military power from their old territories, further developing the unrest into a civil war.

The civil war would culminate in the Chu–Jin contention, during which the imperial library at Xiangyang (present-day Danyang) was burned to the ground. The Jin dynasty would emerge victorious and rule Jinae proper from 206 BCE to 220 CE, creating a cultural identity amongst its populace still remembered in the ethnonym of the Jin people. The Jin expanded the empire's territory considerably, with their military campaigns defining the borders of the present-day East Ochran cultural sphere on the Ochran mainland. Jin expansion and influence reached as far as the Great Northern Steppes, Seonko, the East–South Ochran divide along the Kra Maena river, and the borders of the Tsurushima southern Kitagan peninsula. Jin's involvement in Central Ochran and Lan Na helped establish the land route of the Jade Road and helped develop various Jin-influenced city-states along the route. Jin Jinae gradually became the largest economy of the ancient world. Despite the Jin's initial decentralisation and official abandonment of the Wu philosophy of Legalism in favour of Ruism, Wu's legalist institutions and policies continued to be employed by the Jin government and its successors.

Two Conquest Dynasties

Five Pecks of Rice Rebellion and the return of ethnic Jin rule

Cross-strait War and the Fall of the Huang dynasty

Establishment of the Republic and the Hanaki War

The Corrective Movement and Reestablishment of the Huang dynasty

Reforms and contemporary history

Geography

Climate

Biodiversity

Environment

Political geography

Politics

Political triumvirate

Government

Administrative divisions

Da Huang is constitutionally a unitary state divided into nineteen circuits, three autonomous regions[e], and sixteen direct-administered province—collectively referred to as "Southern Jinae"—as well as the special administrative region (SAR) of Yangcheng. Geographically, all 38 administrative divisions of Southern Jinae can be grouped into six regions: North Da Huang, Northeastern Da Huang, Northwestern Da Huang, South Central Da Huang, Southeastern Da Huang, and Southwestern Da Huang.

Da Huang also has six claimed territories. Many of these territorial disputes are carried over from historical claims, going as far as back as the Jin dynasty.[f]

| Circuits (道) | |

|---|---|

| Claimed Territories |

|

| Autonomous regions (自治区) | |

| Directly administered province Zhílì (直隸) | |

| Special administrative regions (特别行政区) | Yangcheng / Yangcheng (羊城特别行政区)

|

Foreign relations

Trade relations

Territorial disputes

Sociopolitical issues and human rights

Child soldiers

Slavery and human trafficking

Genocide allegations and crimes against the Kra

Government reforms

Military

The Everlasting Army (Jin: 永恒軍; pinyin: Yǒnghéngjūn), more fully called the Standing Army of the Central Plains, (中原帝國常備軍; Zhōngyuán dìguó chángbèijūn) constitutes the military of Da Huang and is amongst the world's largest militaries. It consists of the Ground Force (EAGF), the Navy (EAN), the Air Force (EAAF), and various paramilitary forces that serve as the gendarmerie during peacetime.

The Everlasting Army have a combined manpower of 406,000 active duty personnel and another 345,000 active reserve personnel. The head of the Everlasting Army is the emperor, although this position is only nominal and highly contentious in the current political climate. Under the 1991 constitution, the armed forces were to be managed by the Board of War, which is jointly headed by the Minister of the Army and the Minister of the Navy under the direct supervision of the emperor. In reality, however, the armed forces are split between those loyal to the dajiang (大将; lit. Grand General) Cao Fang of the EAGF and the Royalist party, with some junior officers loyal to the Constitutionalists. Da Huang's official military budget for 2022 totalled JY¥54.09300 billion, accounting for 3.9 per cent of the annual GDP.

According to the constitution, serving in the armed forces is the duty of all Jin citizens. Da Huang still uses the active draft system for males over the age of 18, except those with a criminal record or who can prove that their loss would bring hardship to their families. Males who have not completed their pre-university education, are awarded the Public Service Commission (PSC) scholarship, or are pursuing a medical degree can opt to defer their draft. However, this deferment is subject to varying degrees of success; well-to-do citizens have been known to bribe draft officials, most notably from the EAGF, to dodge the draft entirely. Hence, the poor and less educated are often subjected to varying lengths of active service, with some serving for as long as the maximum five years of reserve training as a Territorial Defence Soldier. This practice has long been criticised, as some media question its efficacy and value. It is alleged that conscripts of the EAGF end up as servants to senior officers or clerks in military cooperative shops. In a report issued in April 2019, EAGF military conscripts are found to have faced institutionalised abuse systematically hushed up by the army authorities.

Historically, Da Huang's military has been mired in corruption and nepotism; the Eastern Depot of the EAGF functions as the political arm of the EAGF military authorities. It has overlapping social and political tasks with civilian bureaucracy, adopting an anti-democratic ideology recently. The military is also notorious for numerous corruption incidents, such as accusations of illegal trafficking, promotion of high-ranking officers in the form of nepotism, and deeply entrenching themselves into the Jin civilian politics.

Economy

Recent econmic history

Income and wealth disparities

Exports and manufacturing

Tourism

Agriculture and natural resources

Informal Economy

Science and technology

Historical

Modern era

Space program

Infrastructure

Transport

Energy

Demographics

Ethnic groups

Languages

Urbanisation

Education

Health

Religion

Culture and Society