Pulacan: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 320: | Line 320: | ||

}} | }} | ||

[[File:Coyolxāuhqui.jpg|left|thumb|180px|A temple decoration depicting the mythological dismemberment of Coyolxāuhqui]] | [[File:Coyolxāuhqui.jpg|left|thumb|180px|A temple decoration depicting the mythological dismemberment of Coyolxāuhqui]] | ||

The most prevalent faith in Pulacan, by far, is [[Cozauism]]. Specifically, the vast majority of Cozauist worshippers in Pulacan belong to the denomination known as Tlaloc-sect Cozauism or the House of Those that Call the Rain (Nahuatl: ''Quiyatlatotecacalli''). Originally developing in modern-day Pulacan during the early 16th century, Tlaloc Cozauism is a highly syncretized {{Wp|pantheism|pantheistic}} religion with heavy influence from both Oxidentalese and Malaioan belief systems. Tlalocine teachings portray a supreme Lord (also identified with {{Wp|Ōmeteōtl}}) possessing infinitely many aspects, chief among whom being {{Wp|Tlaloc}}, the overseer of rains, storms, earthquakes, monsoons and the keeper of {{Wp|Tlālōcān|paradise}}. Worship to the supreme deity thereby uses Tlaloc (and/or other aspects, such as [[Xiuhtecuhtli]]) as an intermediary. Other aspects are associated with anything from major concepts like war to municipalities and even specific natural locations. The essence of the Infinite Lord takes more forms; the permeation of his divine essence through all things is known as ''teotl'' or ''modimo''. Upon death, it is believed that a person's essence returns to the omnipresent ''teotl'', and becomes one of the ancestor spirits known as ''{{Wp|badimo}}'' or ''teyolia''. These spirits permeate all parts of reality, inhabiting natural locations, temples, homes, and limitless other areas. Due to its origin in low-class 16th-century Nahua theology and Komontu folk religion, the Tlaloc sect has far more henotheistic, animistic, and mythological aspects than mainline Zacapine Cozauism. This worship of minor aspects even borders on polytheism with religious movements like the ''Huetecpilcalyotl'' (Great Heavenly Court) school, associated with the [[List of political parties in Pulacan|Moral Government Movement]] political party. | The most prevalent faith in Pulacan, by far, is [[Cozauism]]. Specifically, the vast majority of Cozauist worshippers in Pulacan belong to the denomination known as Tlaloc-sect Cozauism or the House of Those that Call the Rain (Nahuatl: ''Quiyatlatotecacalli''). Originally developing in modern-day Pulacan during the early 16th century, Tlaloc Cozauism is a highly syncretized {{Wp|pantheism|pantheistic}} religion with heavy influence from both Oxidentalese and Malaioan belief systems. Tlalocine teachings portray a supreme Lord (also identified with {{Wp|Ōmeteōtl}}) possessing infinitely many aspects, chief among whom being {{Wp|Tlaloc}}, the overseer of rains, storms, earthquakes, monsoons and the keeper of {{Wp|Tlālōcān|paradise}}. Worship to the supreme deity thereby uses Tlaloc (and/or other aspects, such as [[Xiuhtecuhtli]]) as an intermediary. Representations of these divine elements often Other aspects are associated with anything from major concepts like war to municipalities and even specific natural locations. The essence of the Infinite Lord takes more forms; the permeation of his divine essence through all things is known as ''teotl'' or ''modimo''. Upon death, it is believed that a person's essence returns to the omnipresent ''teotl'', and becomes one of the ancestor spirits known as ''{{Wp|badimo}}'' or ''teyolia''. These spirits permeate all parts of reality, inhabiting natural locations, temples, homes, and limitless other areas. Due to its origin in low-class 16th-century Nahua theology and Komontu folk religion, the Tlaloc sect has far more henotheistic, animistic, and mythological aspects than mainline Zacapine Cozauism. This worship of minor aspects even borders on polytheism with religious movements like the ''Huetecpilcalyotl'' (Great Heavenly Court) school, associated with the [[List of political parties in Pulacan|Moral Government Movement]] political party. | ||

The Tlaloc sect is fundamentally decentralized, with no centralized hierarchy of temples (though hierarchical organizations of temples exist); styles of worship and theology differ between individual temples, sects, and localities. Central to Cozauist worship is sacrifice, typically of specially-prepared foods, libations, flowers and {{Wp|Hell money|joss money}}, among other objects. For public festivals, donated offerings will be ritually sacrificed, along with public performance. Costumed representation of Tlaloc or another divine entity is a common form of worship, as are storytelling, theatrical representation of myth and dance. Some rites augment their rituals with the use of hallucinogenics, including ''{{Wp|Datura|Datura}}'' and ''{{Wp|peyote|peyōtl}}''; these substances were traditionally reserved for {{Wp|Entheogen|shamans}} with botanical knowledge of the plant, and today their religious administration is regulated by Pulatec law. In addition to attending typical Cozauist rituals at local temples, the average ''Quiyatlatotecacatl'' will perform rites at a home or ''calpolli'' shrine for ancestral spirits, as well as hold sacred communal feasts on holidays with sacrifices to both deities and ancestral ''badimo''. Though human sacrifice is not practiced in Cozauism, reflections of its centuries of existence, particularly in ''Quiyatlatotecacalli,'' remain. For instance, during the ''Panquetzaliztli'' ("raising of banners") festival of the 15th month, special cakes bearing the dismembered image of {{Wp|Coyolxāuhqui}} are eaten in groups, possibly reflecting a custom of human sacrifice that involved the dismemberment and ritual consumption of the sacrifice. | The Tlaloc sect is fundamentally decentralized, with no centralized hierarchy of temples (though hierarchical organizations of temples exist); styles of worship and theology differ between individual temples, sects, and localities. Central to Cozauist worship is sacrifice, typically of specially-prepared foods, libations, flowers and {{Wp|Hell money|joss money}}, among other objects. For public festivals, donated offerings will be ritually sacrificed, along with public performance. Costumed representation of Tlaloc or another divine entity is a common form of worship, as are storytelling, theatrical representation of myth and dance. Some rites augment their rituals with the use of hallucinogenics, including ''{{Wp|Datura|Datura}}'' and ''{{Wp|peyote|peyōtl}}''; these substances were traditionally reserved for {{Wp|Entheogen|shamans}} with botanical knowledge of the plant, and today their religious administration is regulated by Pulatec law. In addition to attending typical Cozauist rituals at local temples, the average ''Quiyatlatotecacatl'' will perform rites at a home or ''calpolli'' shrine for ancestral spirits, as well as hold sacred communal feasts on holidays with sacrifices to both deities and ancestral ''badimo''. Though human sacrifice is not practiced in Cozauism, reflections of its centuries of existence, particularly in ''Quiyatlatotecacalli,'' remain. For instance, during the ''Panquetzaliztli'' ("raising of banners") festival of the 15th month, special cakes bearing the dismembered image of {{Wp|Coyolxāuhqui}} are eaten in groups, possibly reflecting a custom of human sacrifice that involved the dismemberment and ritual consumption of the sacrifice. | ||

Thanks to the highly communal nature of worship in Cozauism, whole neighborhoods will collaborate for the hosting of festivals and other religious celebration, including believers of differing faiths. Thanks to centuries of influence and the calendrical focus of Cozauism, the religion defines the Pulatec year. {{Wp|Civic religion|Civil holidays and religious festivals are often one and the same}}. Such festivals are frequent—one occurs for every one of the eighteen 20-day months in the {{Wp|xiuhpohualli|Nahua calendar}}. As such, ''Quiyatlatotecacayotl'' Cozauism is seen as the unofficial [[State religion by country (Ajax)|state religion]] of Pulacan. Minority religions are legally allowed and freedom of conscience is guaranteed under the basic law of Pulacan; atheists and other nonbelievers of religion are typically viewed by default as Cozauists, though are under no legal obligation to worship, perform sacrifices or attend religious ceremonies. | Thanks to the highly communal nature of worship in Cozauism, whole neighborhoods will collaborate for the hosting of festivals and other religious celebration, including believers of differing faiths. Thanks to centuries of influence and the calendrical focus of Cozauism, the religion defines the Pulatec year. {{Wp|Civic religion|Civil holidays and religious festivals are often one and the same}}. Such festivals are frequent—one occurs for every one of the eighteen 20-day months in the {{Wp|xiuhpohualli|Nahua calendar}}. As such, ''Quiyatlatotecacayotl'' Cozauism is seen as the unofficial [[State religion by country (Ajax)|state religion]] of Pulacan. Minority religions are legally allowed and freedom of conscience is guaranteed under the basic law of Pulacan; atheists and other nonbelievers of religion are typically viewed by default as Cozauists, though are under no legal obligation to worship, perform sacrifices or attend religious ceremonies. Despite the integration of Cozauism into Pulatec daily life, many continue to practice indigenous Komontu religious traditions, seeking a more "pure" or "unadulterated" form of worship. These disparate worshippers lack an official body or even single religious identity, putting them afoul of Pulatec law requiring organized religions to register as such with the government. As such, worshippers of folk traditions and traditional practices such as the {{Wp|sangoma}} are forced to operate on the small scale, typically on the level of individual communities, and are typically not recognized in census questions or provided with government aid like other religious groups. | ||

===Music=== | ===Music=== | ||

Revision as of 23:27, 10 September 2024

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Union State of Pulacan | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Pula e ne (SePala) We will be blessed with rain | |

| Anthem: "Pulaletepetlacuicalt" "Pulatec National Anthem" | |

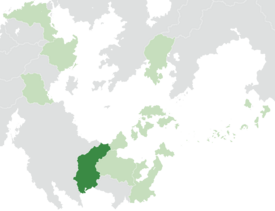

Pulacan (dark green) within the AON (light green) in the Malaio-Ozeros region | |

Map of Pulacan's major cities | |

| Capital | Aachanecalco (executive) Mabesekwa (legislative) Mohembo (judicial) Yztac Tlalocan (administrative) |

| Largest city | Aachanecalco |

| Official languages | SePala, Pulatec Nahuatl |

| Recognised national languages | xKhasi languages, Raji, Nylele |

| Religion (2020) | List

|

| Demonym(s) | Pulatec, Pulatl |

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic with an executive presidency |

• President | Coyotl Gontebanye |

• Chief Minister | Moctezuma Tshireletso |

• Chief of the Ntlo ya Dikgosi | Kȍhà ǂToma |

• Chief Surveyor | Tlaloc Xochiquetzal |

| Legislature | Supreme Colloquy |

| House of Survey Ntlo ya Dikgosi | |

| House of Delegates | |

| Establishment | 1 February 1907 |

• First cave paintings | c. 73,000 BCE |

• Arrival of Bantu tribes | c. 4600 BCE |

• Arrival of first Nahua peoples | c. 1450 CE |

• Itzcoatl's conquest | 1512 CE |

• Return to Heron Empire control | 1542 CE |

• Political Settlement signed | 1907 |

| Area | |

• | 749,856 km2 (289,521 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 46,442,816 |

• Density | 61.93/km2 (160.4/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $1,008,367,349,848 |

• Per capita | $21,712.02 |

| Currency | Pulatec Pula (PLP) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (Central Malaio Time) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (CE) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +69 |

| Internet TLD | .pl |

Pulacan, officially the Union State of Pulacan (SePala: ꦏꦒꦺꦴꦭꦄꦒꦄꦤꦺꦴ ꦪꦄ ꦭꦼꦥꦲꦄꦠꦱꦲꦼ ꦪꦄ ꦧꦺꦴꦥꦸꦭꦄꦕꦄꦤ, Kgolagano ya Lefatshe ya Bopulacan, Nahuatl: 𐐓𐑊𐐰𐐿𐐰𐐻𐑊𐐰𐐻𐐬𐐿𐐰𐐷𐐬𐐻𐑊 𐐑𐐭𐑊𐐰𐐿𐐰𐑌, Tlacatlahtohcayotl Pulacan), is a sovereign country in eastern Malaio. It straddles the continent between the Vespanian Ocean on its south and the Ozeros Sea on its north; it shares land borders with Zanzali to the east, Phansi Uhlanga to the north and Pulau Keramat to the northeast. The current population of 46,442,816 people is spread across 749,856 square kilometers, making the nation one of the most population-dense on the continent at just over 61 people per square kilometer. The arid plains in the south of the nation are divided from the fertile forests and coastal savannahs of the north by a large section of mountains and the Djebe highlands that dominate the country. For centuries, political power has been concentrated in these highlands, lording over the two coasts. The distribution of ethnic groups in Pulacan is heavily influenced by this geography; Nahua peoples, some descended from the former colonial élite, reside mainly on the southern coasts, while large populations of Wampar and other related groups dominate the north. Pala and mixed Pala-Nahuatl peoples (known as coyotec) are by far the most populous groups in the nation, with populations spread throughout, but mostly concentrated in the center of Pulacan. Small populations of the aboriginal xKhasi peoples continue to exist, usually in the hinterlands of the country.

The xKhasi peoples were the first to arrive in what is now Pulacan, living in hunter-gatherer societies for thousands of years before their way of life was hampered by the arrival of more sedentary Komontu peoples in the 47th century BCE. These peoples diversified into numerous ethnolinguistic groups and tribal nations throughout the region, with power and wealth concentrated in the Djebe. Various polities interacted and influenced Pulacan in this time, from the indigenous hegemon of the Great Ngwato Kingdom to the thalassocratic Tahamaja Empire. Contact with traders and religious missionaries from the Heron Empire in modern-day Zacapican was established by the dawn of the 16th century CE, with coastal settlements beginning at the same time. A second, larger wave of Nahua settlement occurred following the 1512 arrival of Itzcoatl, a general sent by the Herons to reestablish relations with the local population. Itzcoatl later went far beyond his mandate and swiftly conquered much of modern-day Pulacan in the name of the homeland. Following Itzcoatl's death, pliable colonial administration was restored in the south; the north eventually fell to Mutulese control and the central chiefdoms became tributary states of Angatahuaca.

The colonial régime saw the widespread introduction of the calpolli system and its adaptation to local economic circumstances. Intended to seamlessly recontextualize the Komontu clan-based social unit into manorial groups under the control of landed colonial elite, the political reality saw a slow and patchwork implementation that at times legitimized and recognized local indigenous power structures where convenient. What state infrastructure that Itzcoatl had established before his death was re-utilized by the colonial governors. A manorial system at times akin to feudalism developed in Pulacan; Komontu megale bureaucrat-warriors were employed by both Komontu vassal polities and some Nahua governors to keep the peace, manage territorial holdings, and collect taxes. The Cozauist temple was heavily promoted as a social binding agent during the colonial period, though it developed many distinct strands of theology from its Oxidentalese overlords in the hands of the Pulatec population. Religion played a significant role in both everyday life and in statecraft, and was the primary justification behind the conquest of Pulacan's northern regions from the Mutul in the 1830s. Endemic problems in the structure of the colony of Pulacan saw a period of total institutional collapse and civil conflict known as the Brothers' War (1892-1907). This war, though bloody, won Pulacan its independence and established a republican government. In the 20th century, Pulacan endured rebellions, the destruction of the Great Kayatman War (1927-1931), and decades of ensuing explosive economic growth and disruptive industrialization. This growth, interrupted by momentary hiccups, came to a halt in the 1990s during a multi-year long recession with global repercussions known as the Lost Decade.

In the modern day, Pulacan is a nation with relatively high levels of economic development, literacy, and access to social services. Politically, a federal and parliamentary system of government is employed, initially designed to balance the interests of the dueling sides in the Brothers' War. Following the terminal decline of its steel industry, the nation's economy has been diversifying, with major strides made in the field of information technology and the manufacture of computing systems. Military involvement in the Fahrani Civil War has polarized a political scene already fraught from a legacy of violence in the Lost Decade era and from contemporary violent political groups like the Djebe Liberation Army (DLA). Internationally, Pulacan is a member of the Forum of Nations and the Association of Ozeros Nations, and its government operates as a full member of the Vespanian Exchange Institute and the Transoceanic Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Etymology

The name Pulacan derives from two separate languages, and reflects the multicultural origins of the country. The word "pula" is a word in SePala, literally referring to "rain". The word carries deep positive significance for many SePala speakers, as it stands for the coming of the Pala peoples from an arid homeland to their current center of population in the often humid and rainy highlands. The suffix -can is Nahuatl in origin, and is used to denote a location, like the suffix -ia in Hellenic. Originally a name applied by Zacapine settlers on the coast to the mountainous highlands of the country on their first arrival, the name eventually became metonymous, and later synonymous, with the polity as a whole, reflecting the eventual takeover of modern-day Pulacan by the collection of highland Pala chiefs.

History

The first settled peoples arrived in what is now Pulacan via the northern plains in 35,000 BCE.

Komontu arrival

The arrival of the ancestors of the Pala peoples in Pulacan is impossible to date precisely. The scholarly consensus supports the idea that the groups split off from the larger Komontu migration in modern-day Phansi Uhlanga in the 5000s BCE. The Komontu entry to Pulacan was likely delayed by resistance from pre-existing groups using the unfavorable terrain as their defense. The early 4th millennium BCE would see the first consistent evidence of Komontu settlement found to date. Some tribes made their way to the southern coasts; their settlements failed to achieve the same level of growth as those in the central highlands, often falling prey to raids by the mountain chiefdoms (Pala: merafe, sing. morafe). In response, many coastal plains groups adopted more nomadic lifestyles, selectively breeding quagga first as pack animals, then by around 1000 CE as mounts. Overland trade connections between the Vespanian and the Karaihe proved lucrative for many kingdoms, allowing for significant wealth generation. As a result, political power gradually shifted to the highlands and allowed for the construction of major settlements like Kaudwane, the one-time capital of Great BaNgwato and oldest continually-inhabited city in Pulacan. From Kaudwane, the Ngwato kingdom expanded to dominate much of the Djebe from the late-9th to early-10th centuries CE through a slow process of conquest, vassalization, and incorporation. The zenith of BaNgwato power, known as Great Ngwato, lasting until the late-14th century, constituted the largest pre-Angatahuacan polity in Pulacan.

The coastal north was subsumed over the 10th century by the Tahamaja Empire. Though Komontu settlements persisted under their rule, some either relocated to modern-day Zanzali and formed part of the WaMzanzi group or partially assimilated into the greater Tahamaja community. The Tahamaja constructed a pelabuhan as the center of their government and trade activities in the region, which later became the commercial center of the modern-day city of Mabesekwa. This city, along with many others in the Ozeros during this time, was jointly constructed by the Tahamajans and a council of merchants from modern-day Tyreseia; the latter came via the city of Shidunadast (nowadays Sumeira in Fahran). This period of Tahamajan rule saw the introduction of the N'nhivara religion to the area and the Uthire script. This script's use in Pulacan co-evolved to resemble the modern-day Mataram script, currently in use in parts of Pulau Keramat. The Uthire script spread along the trade routes to the merafe, where many kings further cemented their power by incorporating a scribal class of bureaucrats as a new state institution of power. The Ngwato kingdom cultivated a literate martial elite, which greatly accelerated their conquest of the Djebe. This class, responsible at various times for warcraft, administration, and retainer duties for dikgosi, eventually formed into a distinct class known as megale (sing. mogale). The eruption of Mount Siriwang in 1353 greatly disrupted the world's mercantile enterprises, with the Tahamaja suffering a fatal collapse in authority and losing control of northern Pulacan to the Mutul, who ruled the area until the late 18th century. The subsequent mass crop failure induced a famine and period of stagnation in Great Ngwato that led to its slow decline and collapse around 1375 into local fiefdoms and more decentralized power.

Angatahuacan colonization and Itzcoatl

Merchants from Angatahuaca in modern-day Zacapican first arrived in southern Pulacan around 1450 CE, with limited bands of settlers following shortly after. The original purpose of such settlement was to augment the Angatahuacan thalassocracy (known also as the Heron Empire); the southern coastal plains provided easy access to hardwood for repairing ships and the locals could be traded with for supplies. Due to the nature of these early settlements, the first half-century of Nahua presence was extremely limited, with traders largely sticking to the coast, barring a few notable commercial expeditions into the highlands. A notable exception were Cozauist priestly societies in Oxidentale, who quickly organized missionary expeditions to Malaio. Initially seeing the newfound region as a perfect place to begin spreading their faith, many missionaries found difficulty in spreading their exclusive, monotheistic religion in a region accustomed to a kaleidoscope of beliefs. Pre-existing Komontu religious practices enjoyed continued widespread patronage. Eventually, a theological connection was formed between minor rain spirit Tlaloc and a major Komontu rain deity, seeing the genesis of a highly-syncretic and divergent form of Cozauism much more popular in Pulacan than its original form. Some highland rulers were early adopters of this Tlaloc-centered religion; many saw it as a way to increase trade and friendly relations with a powerful foreign nation as a way to back themselves against their neighbors, while others saw the priesthood as a useful tool of state without sacrificing their previous faith wholesale, emulating the state use of Uthire scribes in the previous centuries.

After several decades of reconstruction and adjustment, Angatahuaca began rebuilding its Red Fleet of trade vessels and warships. In the 1510s, a concerted effort was underway to assemble a fleet and army to establish direct control over the southern Pulatec region in particular. In 1512, the disgraced noble and military commander Itzcoatl landed near the modern-day city of Cuicatepec with a force of 7,000 Zacapine regulars and numerous Onekawan mercenary forces. Almost immediately following his landing, however, disagreements surrounding their mission's ultimate direction developed between Itzcoatl and his commanding staff. Itzcoatl, wishing to expand the empire and spread faith in Tlaloc, developed a desire to not only control the southern plains, but the central highlands as well; by controlling the highland dikgosi, Itzcoatl could profit from the trade routes from the Vespanian to the Ozerosi and Karaihe peoples directly. Controlling such trade would profit the empire greatly and garner personal fame for Itzcoatl. From around 1521, Itzcoatl recruited significant coyotec auxiliaries to augment his forces and unleashed a series of wars of conquest to subdue the Djebe. This Djebe Fire War was Itzcoatl's first major disobeyance of his orders from the homeland; with little contact between the mother country and his forces and the majority of the Red Fleet being with Itzcoatl meant that the Zacapine leadership was nearly powerless to halt his activities even if they understood the full extent of his actions. Such a risky investment on the Zacapines' part was seen as acceptable due to Itzcoatl's perceived skill and prestige back home—this same skill motivated his choice to violate his orders and go rogue. After a decade of consistent warring and complex tributary negotiations, Itzcoatl secured personal military control over most of central and southern Pulacan. He then bolstered his control through the creation of a new state-sponsored Tlaloc dualist priesthood based in the planned city of Ytzac Tlalocan, which served as Itzcoatl's capital and for many centuries after as the religious epicenter of Pulacan. Defying his imperial overlords, Itzcoatl declared himself huetlatoani (paramount governor or high king) and ultimate authority in the region of Pulacan.

Heron suzerainty

Despite Itzcoatl's best efforts, his personal fiefdom would not last much beyond his death. To support his rule, he had adeptly built vast and complex networks of patronage, suzerainty, and alliances with himself at the center. Without the authority of his charisma and his armies, the alliances collapsed. Massive infrastructure projects such as a network of mountain highways through the Djebe were slowly downsized, then totally halted as tributary funds dried up and the royal court collapsed. Itzcoatl's remaining loyalists tried and failed to assert control over the area as more and more Pala statelets began breaking free, with some reverting to a pre-Itzcoatl status quo while others adapted the Nahua ways and technology as a permanent tool of statecraft. Ultimately, Itzcoatl's son and successor Mixpapalotl was forced to appeal to Angatahuaca for assistance. In early 1542, the Angatahuacans sent harsh demands: for the price of their military assistance, Mixpapalotl would have to swear loyalty to the Heron Empire on pain of death, and his son and heir apparent was to be sent to Oxidentale as a political hostage. Backed into a corner by continual raids on the outskirts of Ytzac Tlalocan, Mixpapalotl eventually assented; he met the Zacapine troops at Cuicatepec in 1544 near the site of Itzcoatl's initial landing. At the 1559 pitso (congress) of Ytzac Tlalocan, they were forced to settle for control of the south owing to a lackluster campaign pushed by a lack of local support. The highland statelets were to swear loyalty to this re-invigorated Angatahuacan rule, but as vassals with significant internal autonomy. Much of the merafe agreed to this compromise, with an understanding that the Angatahuacan governor would treat them with benign neglect. As a result of this dynamic, the merafe continued to undergo significant political change and cultural growth in the centuries following the pitso of Ytzac Tlalocan.

Mixpapalotl's seat of power remained in the burgeoning religious and bureaucratic center of Ytzac Tlalocan, but the Heron leadership demanded he appoint an attendant tlatoani (governor) based in Aachanecalco. As this supervisor required approval from the metropole upon appointment, he was in effect the supreme governor of the Pulacan colonies, despite being nominally below the Itzcoatl lineage's rank. By the time Mixpapalotl met his demise in 1571 and his son Coxcoxtli returned to take his throne, the position of huetlatoani had been effectively whittled down to a ceremonial figurehead. The grand palaces and temples of Ytzac Tlalocan had become a gilded prison from which the monarch could very rarely escape. Coxcoxtli had been conditioned to fill this role after decades of grooming in the Heron motherland. From this point, the kings wielded only minor religious and moral power, serving as spiritual heads of the Tlaloc Sect, as conflict mediators and as little else of importance for the vast majority of Pulateh living outside Ytzac Tlalocan.

Brothers' War

The second half of the 19th century saw a marked and steady decline in Angatahuacan power over Malaio. Friction between local plantation elites in Cuhonhico (modern-day Phansi Uhlanga) and their colonial overlords saw the province becoming all but independent from Oxidentale. The 1830s reconquest of the Mutul's remaining Karaihe colonies, initiated by the tlatoani Achitomecatl, bought short-term loyalty from the merafe, but as Angatahuaca weakened, the tlatoani continued to lose authority. Faced with a sudden lack of political power, a rush of new ideologies and movements generated throughout the long 19th century as Pulateh dreamed of what could come next. Beginning in the 1870s, foreign-educated intellectuals, largely from former megale families, would begin Pulacan's own political publishing industry as dissent became commonplace. Widespread open conflict, a period later known as the "Brothers' War," began in the early 1890s as dissent turned to armed struggle. The war was multifaceted, with alliances between the numerous armed groups constantly in flux. Some factions, mainly those dominated by the southern colonial elite, initially supported continued Heron suzerainty until economic and political turmoil in Oxidentale began to negatively impact the Pulatec economy. As the war progressed to its final stages, these former loyalists became the conservative wing of the pro-multiracial-democracy faction, led by many megale-intellectuals. Some, but notably not all, of the merafe's ruling élite rose up in revolt throughout the war, initiating guerrilla conflicts in order to establish independence from Aachanecalco. As centuries of colonial rule had permanently altered these communities, inter-morafe conflict over resources, boundaries, and strategic points of control quickly broke out. Both the pro-republicans and Heron colonial administration fought these merafe and each other, condemning the region to nearly two decades of bloody conflict.

With Angatahuaca's own revolution in the first decade of the 20th century, the colonial garrison was withdrawn to stamp out revolutionary activity in the home provinces. Xolotecatl Acuixoc, future strongman leader of Zacapican, began his career during this conflict as a low-level Angatahuacan naval commander in southern Pulacan before being recalled to the mother country. The Brothers' War was brought to a close by an armistice in late 1906 after years of significant trans-oceanic support between the embattled republicans in Oxidentale and Malaio. The ensuing Political Settlement, a draft constitution which enshrined peace between Pulacan's warring factions, came into effect on 1 February 1907. The mutual cooperation during their respective revolutions between the new revolutionary regimes of Zacapican and Pulacan fostered a decades-long relationship between the two countries characterized as "sister republics," portrayed by their political leaderships as allies in the battle against colonialism and imperialism—a characterization that came to be heavily challenged in the 1960s and 1970s.

Hanaki War and beyond

Main article: Hanaki War

The Great Kayatman War, also known as the Hanaki War, was a watershed moment in modern Pulatec history. The war, which lasted from 1927 to 1931, thrust the young Union State into conflict with a revanchist and Komontu ethnonationalist regime in Zanzali, along with their allies. Though Pulacan eventually emerged victorious in the war alongside a coalition of nations, the conflict proved costly. WaMzanzi troops had occupied the north of the country, where significant amounts of civilian infrastructure was destroyed and ethnic violence was perpetrated against local inhabitants, especially the Tuganani. The ethnic cleansing of the north triggered a millions-strong internal refugee crisis that continued after war's end. This demographic upheaval was later augmented through waves of immigration spanning throughout the mid-20th century. As part of postwar rebuilding efforts, longtime president Dumelang Tsogwane initiated a series of industrialization reforms that, among other things, subsidized the foundation of new industrial concerns or the conversion of old agrarian calpolleh. Intended as a solution to Pulacan's lagging industrialization, massive unemployment rate and need to rebuild simultaneously, the program proved successful. Industry, particularly steel manufacturing, quickly dominated Pulatec exports and urbanization rapidly increased nationwide, often at the cost of ballooning industrial slums. Inter-ethnic conflict between the disparate immigrant groups and with previous locals also increased, inflamed by prevalent overcrowding.

The late 1950s and into the 1960s saw major efforts made to beautify and re-engineer Pulacan's cities in order to improve the standard of living. The Ghanzi Plan, authored by then-Chief Minister Sechele Boko, created a ten-year program (from 1956 to 1966) for urban renewal funded in large part through earnings in the booming state-owned MAUN steel conglomerate. Done as much to promote steel consumption as it was to improve urban life, the Ghanzi Plan was nonetheless successful in modernizing much of Pulacan's urban spaces. It is argued, however, that the consumption boost only prolonged the steel industry's unsustainable growth—and worsening the ensuing crash, which manifested as Pulacan's Lost Decade. Lasting roughly from 1992 to 2002, the Lost Decade saw the utter collapse of Pulacan's steel production, falling from a dominant national industry to a small part of the economy. The contagion of the steel collapse impacted other businesses within Pulacan and globally, as well as prompting a period of political crisis as a series of short-lived and unpopular governments failed to produce lasting solutions. The crisis culminated in the May Coup of 1997, a failed coup d'etat attempt led by National Gendarmerie colonel T.B. Tshola. While unsuccessful, the May Coup highlighted Pulacan's political dysfunction and incentivized the formation of the national unity government that finalized the path to economic recovery.

Geography

Climate

Government

Pulacan is governed as a federal state organized along the principles of parliamentary democracy. The federal government, though large, has defined separation of powers. For example, the legislature holds significant independent power from the executive branch. At the core of the Pulatec political system lie calpolli districts, self-governing communities based around business, enterprise and/or shared land use. Collections of calpolleh are grouped into municipalities known as altepemeh (sing. altepetl). The governments of said altepemeh are then grouped and subordinated to that of a tlatocayotl, typically translated as "department." Tlatocayome serve as the top-level administrative division below the national government. Each level is tasked with various responsibilities; typically, calpolleh and altepemeh collaborate to provide municipal services, from healthcare to sewage and public transportation. Historically, calpolleh embodied a function that was less economic and more analogous to historical Pala clannic groups; to this day, many calpolleh find themselves under the nominal authority of a kgosi, or traditional tribal chief, though in the modern day their authority is typically cultural. In some cases, their power is economic as a result of modern investing of royal wealth—some calpolleh groups have dikgosi as investors, and such a practice is often viewed as separate forms of authority from those clan-like calpolleh that trace familial relations to the chief's tribe.

Pulacan's nominal head of state is the State President, who fulfills a largely ceremonial role in the functions of government.

The judicial system of the Union State works [like this]. Law enforcement is provided by the Yocoxcaquizque Pulacan (lit. "Peace Guardians of Pulacan"), which serves as an umbrella agency that oversees and coordinates altepetl-level policing units.

Supreme Colloquy

The legislative arm of the Union State is embodied by the tricameral Supreme Colloquy. The entire nation is subdivided into electoral districts for the House of Delegates, designed to be of equal population size and to follow the proportional party representation electoral model. The House has the power to legislate issues covering the whole country (though it must pass review by the Ntlo ya Dikgosi and the House of Survey first). From this House, a Chief Minister will be elected. Typically the head of the party with the most seats, the Chief Minister will serve both as the executive of the Union State and as the leader of the Pulatec Cabinet. As of 2022, the current Chief Minister is Moctezuma Tshireletso of the Nguzo party. The House of Survey serves as an active check on the actions of the Chief Minister and the House of Delegates. Assembled from a number of the nation's top legal experts, the task of the House of Survey is to defend the rights of the people enshrined in the Political Settlement against actions by the rest of the government. In effect, thanks to their positions in government and legal training, the House of Survey serves as a kind of prosecuting attorney against the government on behalf of the people's rights, including those of the tribes and their leaders.

Amphyctyonic League

The term "Amphyctyonic League" is a scholarly exonym used to refer to the political sphere of influence of the dikgosi, or tribal chiefs, who typically sit at the head of the tribal nations of Pulacan. The leadership of these tribes is represented by the Ntlo ya Dikgosi, or the Council of Chiefs. This body operates as an advisory chamber for the Pulatec government and as a kind of third house in the Legislative Assembly. This body is the weakest in the tricameral system, having little power to formulate its own legislation. It can, however, open investigations into central government officials' conduct, hold advisory sessions on bills and drafts, and even subpoena and compel persons of interest to testify before them. Additionally, the speaker of the Ntlo ya Dikgosi can sit in on Cabinet meetings at their pleasure to serve as an advisor, or represent the other monarchs at formal events domestically and abroad.

A political innovation that the dikgosi have brought to the Pulatec political world is the kgotla. The kgotla is somewhat akin to a Latin open-air forum or a speaker's corner and has come to define the architecture of many a Pulatec community. These locations are often large public squares in front of palaces of government filled with greenery and an outdoor throne. Traditionally, upon this throne, a kgosana or "little chief" would sit at regular intervals to hear complaints and petitions from the populace and either order remedies, dismiss them entirely, or refer them to the kgosi in the capital. Originally, the dikgosana was a term for a hierarchical pyramid of power, filled with male heads of influential family groups, clans, and households subordinate to a tribe who were important in decision-making and governing the people within. The original function of the dikgotla has fallen largely out of use with the advent of modern means of administration, though the kgosana position still exists within tribal royalty. The public grievance-airing ceremony at kgotla is still widely today in Pulacan. Following the Political Settlement, dikgotla are used as a means of electing leaders within a local calpolli or that calpolli's governing altepetl in a form of nested-council democracy. Throughout a representative's term, they will be frequently "summoned" by their constituents to the kgotla in order to report their initiatives and answer questions. Additionally, the dikgotla serve as polling places, places for public votes on local initiatives, and grounds for resolving intra-calpolli disputes by the community (usually with a legal expert present). In major cities, multiple dikgotla will meet in different neighborhoods to legislate on local matters and settle disputes on the rulers' behalf, as well as to elect representatives to a larger assembly that functions like a city council. From there, this council legislates city-wide issues and elects a city-wide dikgosana. Due to the myriad demands a kgosi might face at once, certain dikgosana might be delegated to fill in tasks while the kgosi is indisposed. Most commonly, some dikgosana are temporarily empowered to conduct day-to-day business or ceremonial affairs while the kgosi attends meetings of the Ntlo ya Dikgosi, or in the case of kgosi Motswagole III Tshekedi, while he is posted to a field command with the Union Security Forces.

Military

The government of Pulacan exercises its national security interests through the nation's military, the Union Security Forces. The Security forces are subdivided into the Union Army, the Union Navy, the Union Air Force, the Union Central Intelligence Directorate, and the National Gendarmerie. With an estimated 250,000 active-duty personnel, Pulacan fields the largest standing military in Malaio. All citizens between the ages of 18 and 30 are eligible for conscription. The draft has not been used to provide manpower for the military since the early 20th century, however, and so the Security Forces function as an all-volunteer professional fighting force.

Much of the military's numerical strength is devoted to internal security and national defense, with external offensive planning often a secondary concern. Historically, the Security Forces and their immediate predecessors have been used to protect national security interests inside the country as much as they have engaged in traditional state warfare. The Forces trace their modern origin to the 19th-century Righteous War, when Zacapine colonial forces and Pala chiefdoms waged a war of irredentist conquest against the crippled colonial empire of the Mutul in the Ozeros. The war led to the conquest of northern Pulacan and the acquisition of a Karaihe coastline by the joint forces, but the gains were quickly marred by the rapidly-ensuing Brothers' War. This saw a civil war between Zacapine forces and the growing Republican movement in Pulacan pitted against a loose coalition of Pala kingdoms. The war was multifaceted and long, causing high numbers of casualties and seeing many betrayals and switching sides by multiple factions. Eventually, the fighting was ended in the Political Settlement that brought about the foundation of Pulacan's modern political system and the Union Security Forces. As such, when it was created, the memory of violent civil conflict was fresh in the minds of many, and the force was created with the goal of preventing internal political instability foremost.

The commander-in-chief of the Union Security Forces is the President of Pulacan, currently Coyotl Gontebanye. In practice, much of their power is delegated to the Security Secretary, which represents civilian government in the military hierarchy and works alongside the Defense Staff Council, which sees the highest-rank flag officers of all the branches assembled in one joint command structure.

Foreign Affairs

The foreign affairs interests of Pulacan are represented by the Secretariat of External Affairs. Following the Brothers' War, Pulacan and Zacapican have maintained an often-close relationship, though not without controversy. The two states' bond was tested most severely from the late 1960s to the 1980s, as various Chief Ministers opposed Zacapican's military interventions in modern-day Phansi Uhlanga. The political dynamics of Malaio and the Ozeros Sea region see Pulacan negotiating the competing spheres of influence maintained by Pulau Keramat, Zacapican, Onekawa-Nukanoa and other states.

Education

Education in Pulacan is publicly-funded, with mandatory primary and secondary education. Upwards of 99% of Pulacan's population, regardless of gender, is literate. The first phase of primary education (from Grades 0-3) is typically provided by a calpolli workplace as a part of its childcare and nursery services. From Grade 4 (typically ages 9-10) onwards, students attend separate school facilities run directly by local municipalities (altepemeh), adhering to national education guidelines. This second phase of primary education ends with Grade 6 and a nationwide standardized exam. A further exam is administered at the end of Grade 9 (ages 14-15) to determine a student's academic interests, as well as placement in a secondary school. The final three years of secondary education, reflective of the history of the calmecac system, typically sees students undergo specialized education to prepare them either for the workforce, the bureaucracy, or further education. The national Education Secretariat has the ultimate authority to set benchmarks, requirements, and goals, but local school administrations have flexibility to augment the curriculum to meet local needs and expectations. For instance, all students are expected to develop dual fluency in SePala and Nahuatl, but provisions are made for the learning of regional languages. School uniforms are required in all schools from Grade 4 until the completion of secondary education (typically ages 17-18). A final matriculation exam is held at the end of Grade 12; passing is mandatory, with retakes and study help often provided.

Until recent decades, a large number of Pulateh attended a calmecac, or boarding school, for their secondary education. Initially developed as offshoots of Cozauist temples during Itzcoatl's reign, numerous organizations came to found such boarding schools in the intervening centuries. For example, calpolleh would at times found vocational calmecaceh to train future members, while tribal elites and megale families would establish aristocratic finishing schools. From the late 1950s onward, the calmecac system fell out of fashion as a large construction boom saw the rapid expansion of urban infrastructure and government facilities. With this growth came widespread access to secondary day schools, which now make up for the vast majority of secondary education in the country. While boarding schools (particularly priestly seminaries) still exist, many contemporary organizations prefer educational outreach in the form of extracurricular programs and adult education courses.

Unlike compulsory education, tertiary education in Pulacan is exclusively offered by the state. Often run as altepetl- and nationally-subsidized educational calpolleh, universities and colleges offer courses in the sciences, humanities, arts, and design as well as serving as nodes in the nation's network of research and development facilities alongside state-run dedicated laboratory facilities. Pulatec universities frequently collaborate with outside universities, as well; Pulacan is a member of the Ozeros University system, which facilitates academic communication and student transfer between the academic communities of AON member states. Additionally, the OUS directly runs a satellite campus in the city of Kuroranu Taihu open to enrollment from all member states of the AON. In recent decades, universities in Pulacan have pioneered significant advancements in the areas of information technology, cybersecurity, architecture, biomedical engineering and agricultural sciences.

Economy

Pulacan maintains the third-largest economy by output in the Malaio-Ozeros region, with a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of $1.008 trillion and a per-capita GDP of $21,712 as of 2022. As an industrialized, middle-income country, Pulacan's primary industries are refining precious metals such as diamonds; manufacturing, especially in the automobile realm; and exporting electrical energy to nearby nations. The industrial sector is heavily reliant on foreign trade, especially for exports. Pulacan's primary trading partners are Pulau Keramat, Zacapican, Zanzali, and Onekawa-Nukanoa, largely based off of historic ties and proximity. Most of Pulacan's exports are to other nations within the Malaio-Ozeros region or to Zacapican. Economic activity is regulated by the Secretariat of Trade and Economics.

Pulacan is a member of the Union State (Nahuatl: Cetliliztli Tlatoloyan), a system of interconnected agreements and pacts with the United Zacapine Republics. Along with Zacapican, Pulacan is one of the two nations with economies based on the calpollist mode of production. Pulacan's variation of the calpollist system differs from Zacapican primarily in the industrial manufacturing sector. There, it evolved from incentive-based campaigns towards existing clan-based calpolleh as opposed to in Zacapican, where many old rural calpolleh were forcibly supplanted by the dictatorial Xolotecate. Pulacan's industrial and rural calpolleh alike are often integrated with their presiding clans in a way usually reserved for the most traditional of rural calpolleh in Zacapican. Clannic and familial management ties have diminished somewhat over the course of the 20th century following periods of internal migration, immigration, wars and economic change. Despite what remains of traditional management, calpolleh are not owned by a single person or entity, and are often managed in terms of nested self-management.

Pulacan's industry is tied to its Zacapine counterparts through a series of formal and informal agreements. Many products, for example, will be assembled partway in one nation, then shipped to the other to be completed in sold in the destination nation's regional market. Pulatec raw materials, like diamonds and platinum, are utilized in Zacapine manufacturing as well as the manufacturing of many nations around the world to some extent. This network of integration is codified both by the Union State and the superseding Transoceanic Co-Prosperity Sphere (TOCPS).

The service sector of Pulacan is relatively small yet growing. Often, service jobs are tangentially linked to the industrial sector. The industrial arts, design, and architecture fields are niches within both the Malaio-Ozerosi and Union State economic landscapes that Pulacan has grown to dominate. The Djebe Industrial Arts and Design College (DIADC), headquartered in Mohembo, hosts some of the world's most prestigious curricula on the subjects. The most prominent example of this service dependence on industry comes from the information technology sphere. Coltan and other rare earth metals are comparatively accessible for Pulatec manufacturers, whether from local sources or from West Itayana via the TOCPS common market. Beginning in the 1980s, a robust yet small-scale industry surrounding the manufacture of low- and mid-range processors and other computer chips sprang up in the south of the country around Cuicatepec. Small-scale manufacture of high-end integrated computer systems followed in the late 1990s as chip technology advanced. To service these machines, a native information technology and computer technician sector came in vogue in the early 2000s. As the IT industry is less tethered to factories or single locations, the sector exploded and decentralized across the country during the early 21st century, in tandem with the concurrent rapid spread of the Internet and digital technology. Currently, IT-based calpolleh will typically rent office spaces or entire buildings; software technicians, IT specialists, and hardware repair technicians will share the space in order to provide holistic digital maintenance services.

Transportation

Culture

Ethnic Groups

Pulacan is an ethnically diverse nation containing numerous groups. Coyotec, or peoples descended from Nahuas and various Komontu groups, are the majority ethnic group and make up 64.6% of the population. People identifying as distinctly Nahua with no Komontu sense of identity make up only 2.4% of the population, and reflect more recent migration trends from Zacapican, as well as Cuhonhicah populations fleeing the Third Uhlangan Civil War. Conversely, peoples classed as Komontu without Nahua cultural identity make up 18.6% of the population. This group is majority comprised of SePala people. The largest ethnic group outside of Komontu or Nahuan peoples are the Tuganani people. Largely concentrated on the northern coast of Pulacan, they consist of around 8% of the nation's population today. The Tuganani are generally considered to be the aboriginal people of Pulacan's Karaihe coast, though their numbers were significantly reduced through millennia of migration, war, and conquest. In modern times, their homeland was the most ravaged in Pulacan by the Hanaki War, leaving hundreds of thousands displaced or dead. Post-war internal migrations saw the scattering of Tuganani people across Pulacan, with predominantly Pala and coyotec ex-soldiers taking their place as part of rebuilding efforts. Today, efforts are being made to preserve the culture of the Tuganani internal diaspora, and a cohesive community is again forming in the north around the binational city of Kuroranu Taihu.

Numerous small ethnic communities inhabit Pulacan's major cities as a product of 20th-century immigration trends. Though modest compared to mass migrational influxes to nations like Zacapican, Pulacan still experienced large influxes of foreign nationals following the Hanaki and Monsoon Wars. Many of these immigrants moved into the Republic, as integrating into the tribal nations' clannic structures presents a much steeper obstacle to newcomers. Upwards of 7.2% of Pulacan's population is made up of these immigrants or their descendants. Major nations of origin include Kembesa, Ludvosiya, the Mutul, Phansi Uhlanga, and Zacapican. The xKhasi people, descendants of indigenous pre-Komontoid nomadic populations, still inhabit stretches of the foothills in the southern Djebe. Numbering only 0.2% of Pulacan's people, their small size, cultural practices and lifestyle have made them subject to continued persecution historically. Only with modern efforts to preserve their way of life have the Khoisan found a place to coexist with sedentary Pulatec society, though issues of prejudice, farmland encroachment on traditional lands, and substance abuse still plague the community. In 2002, the Khoisan were granted a seat on the Council of Chiefs, or Ntlo ya dikgosi, granting them for the first time political representation to those that chose to remain nomadic. The first and current representative is Kȍhà ǂToma, who now serves as the rotating head of the Council.

A Pitz-like ballgame player in Cuicatepec

Religion

The most prevalent faith in Pulacan, by far, is Cozauism. Specifically, the vast majority of Cozauist worshippers in Pulacan belong to the denomination known as Tlaloc-sect Cozauism or the House of Those that Call the Rain (Nahuatl: Quiyatlatotecacalli). Originally developing in modern-day Pulacan during the early 16th century, Tlaloc Cozauism is a highly syncretized pantheistic religion with heavy influence from both Oxidentalese and Malaioan belief systems. Tlalocine teachings portray a supreme Lord (also identified with Ōmeteōtl) possessing infinitely many aspects, chief among whom being Tlaloc, the overseer of rains, storms, earthquakes, monsoons and the keeper of paradise. Worship to the supreme deity thereby uses Tlaloc (and/or other aspects, such as Xiuhtecuhtli) as an intermediary. Representations of these divine elements often Other aspects are associated with anything from major concepts like war to municipalities and even specific natural locations. The essence of the Infinite Lord takes more forms; the permeation of his divine essence through all things is known as teotl or modimo. Upon death, it is believed that a person's essence returns to the omnipresent teotl, and becomes one of the ancestor spirits known as badimo or teyolia. These spirits permeate all parts of reality, inhabiting natural locations, temples, homes, and limitless other areas. Due to its origin in low-class 16th-century Nahua theology and Komontu folk religion, the Tlaloc sect has far more henotheistic, animistic, and mythological aspects than mainline Zacapine Cozauism. This worship of minor aspects even borders on polytheism with religious movements like the Huetecpilcalyotl (Great Heavenly Court) school, associated with the Moral Government Movement political party.

The Tlaloc sect is fundamentally decentralized, with no centralized hierarchy of temples (though hierarchical organizations of temples exist); styles of worship and theology differ between individual temples, sects, and localities. Central to Cozauist worship is sacrifice, typically of specially-prepared foods, libations, flowers and joss money, among other objects. For public festivals, donated offerings will be ritually sacrificed, along with public performance. Costumed representation of Tlaloc or another divine entity is a common form of worship, as are storytelling, theatrical representation of myth and dance. Some rites augment their rituals with the use of hallucinogenics, including Datura and peyōtl; these substances were traditionally reserved for shamans with botanical knowledge of the plant, and today their religious administration is regulated by Pulatec law. In addition to attending typical Cozauist rituals at local temples, the average Quiyatlatotecacatl will perform rites at a home or calpolli shrine for ancestral spirits, as well as hold sacred communal feasts on holidays with sacrifices to both deities and ancestral badimo. Though human sacrifice is not practiced in Cozauism, reflections of its centuries of existence, particularly in Quiyatlatotecacalli, remain. For instance, during the Panquetzaliztli ("raising of banners") festival of the 15th month, special cakes bearing the dismembered image of Coyolxāuhqui are eaten in groups, possibly reflecting a custom of human sacrifice that involved the dismemberment and ritual consumption of the sacrifice.

Thanks to the highly communal nature of worship in Cozauism, whole neighborhoods will collaborate for the hosting of festivals and other religious celebration, including believers of differing faiths. Thanks to centuries of influence and the calendrical focus of Cozauism, the religion defines the Pulatec year. Civil holidays and religious festivals are often one and the same. Such festivals are frequent—one occurs for every one of the eighteen 20-day months in the Nahua calendar. As such, Quiyatlatotecacayotl Cozauism is seen as the unofficial state religion of Pulacan. Minority religions are legally allowed and freedom of conscience is guaranteed under the basic law of Pulacan; atheists and other nonbelievers of religion are typically viewed by default as Cozauists, though are under no legal obligation to worship, perform sacrifices or attend religious ceremonies. Despite the integration of Cozauism into Pulatec daily life, many continue to practice indigenous Komontu religious traditions, seeking a more "pure" or "unadulterated" form of worship. These disparate worshippers lack an official body or even single religious identity, putting them afoul of Pulatec law requiring organized religions to register as such with the government. As such, worshippers of folk traditions and traditional practices such as the sangoma are forced to operate on the small scale, typically on the level of individual communities, and are typically not recognized in census questions or provided with government aid like other religious groups.

Music

Entertainment

Television in Pulacan is dominated by the state-run corporation, Television Broadcasting of Pulacan (Huecachializtli Machitipepeyaca Pulacan, HMP). From its inception in 1950 to the late 1970s, all television broadcasting was done through HMP and funded via a TV licensing scheme. Then, as now, the network maintained 3 channels, which were largely devoted to news and documentary programs. These channels were at first nearly identical in programming, differentiated only by language: HMP1 broadcast in SePala, while HMP2 broadcast in Nahuatl and HMP3 broadcast in Raji. A fourth channel, HMP4, was utilized solely by local stations for emergency broadcasts. Language dubbing, a practice inspired by its frequent use in the local cinema industry, became industry standard for television. A forceful deregulation of the industry in 1974 saw the legalization of local television channels, with larger freedoms on the types of programs to be shown. These stations would use a mixture of on-air advertisements and government grants to fund their operations. Very quickly, networks dedicated to comedy shows, fictional dramas, historical shows, and children's programming cropped up in every major city in the country. Some stations began forming syndicates, in which the rights to certain popular programs would be shared between multiple local stations and consequently aired at the same time. Because private television networks are illegal in Pulacan, these syndicates of private local broadcasters are the closest replicants. The networks are also syndicated with local and national sports leagues to broadcast matches of (!baseball), association football, and pitz.

Certain content, such as movies (television content in Pulacan must legally be "made for television" to be aired), music videos, religious programming, and other alternative shows are broadcast on illegal pirate networks, often euphemistically referred to as "HMP4" due to the highly local pirate broadcasters using HMP4 during non-emergencies as their own channel. When HMP failed to secure the right to broadcast the wildly-popular animated Zacapine show Tlalyaohuitl in 1984, pirate networks quickly got their hands on copies of the show and broadcast it themselves. This simultaneously generated much ire from the government and positive attention from the populace. As such, pirate networks are a staple of entertainment in Pulacan, though they are often transitory and ephemeral thanks to constant police crackdowns and prosecutions. In some cities, they maintain a younger estimated viewing range than traditional television thanks to alternative programming. Some avant-garde comedy show ideas have even been broadcast on pirate networks around major cities like Ytzac Tlalocan and Mabesekwa to test their market feasibility before the rights and concepts are picked up by legitimate "local syndicates" or HMP. Traditional television has garnered an older and older viewerbase in recent decades, though this trend was bucked for a time in 2019, when a Zacapine tourist posted to Rad.Io screencaps from a Pulatec historical drama on Itzcoatl being broadcast on HMP2. The post expressed admiration for the piece's entertainment value despite the subject being a "stuffy piece of history filled with conquerors and murderers." The post was quickly trending on Zacapitec internet spaces. The ensuing demand for the dramas abroad saw HMP reach deals with worldwide streaming services over the following year to have their back catalog distributed. The sudden worldwide interest in the alacrity of the dramas for their mixing a mildly educating storyline with intrigue, storytelling and character development was amusing to many Pulatecs, who often shared sentiments on social media such as "Thanks to the internet, my grandmother and 18-year-olds in 'the mother country' now enjoy the same shows. Brilliant!"

The cinema industry has existed in Pulacan since the 1920s, when a stage theater in Aachanecalco was converted to show films and Nahuatl-language duplicate film stock was imported from Zacapican. The medium was only restricted by langauge for a few years, however, as new distribution companies employed whole divisions dedicated to cutting out intertitles from silent films and adding translated versions. By 1930, multiple cinema houses existed across the nation's major cities, broadcasting films in SePala, Nahuatl, and even Pulaui languages in the north. The advent of so-called "talking pictures" or talkies was a significant challenge to the cinema industry, and theaters were slow to upgrade. The entire industry almost suffered a total systematic failure around the year 1933 as new silent films became increasingly hard to source from abroad. The nascent Pulatec entertainment industry was unable to output at a speed to balance out the deficit. Numerous theaters and distribution companies were forced to shutter, as sources for funding dried up and the cost of upgrading projection equipment grew too steep. The subsequent year of 1934 became known in popular culture as "the Year without a Movie," symbolizing the cultural grip this newfound art form had on the masses and the significant impact of such a dearth of material. Such a hold could not be left empty for long, and soon, talking movies were being imported and localized by voiceover artists. This procedure, though complicated at the time, was nevertheless instrumental in revitalizing Pulacan's film industry. To this day, voiceover actors and singers that dub musicals into local languages often receive as much fame and publicity as standard screen actors in Pulacan.

The advent of the Internet has, as in the rest of the world, transformed Pulacan's media landscape. Once connection speeds and file transfer limits were large enough to allow for video-sharing, television and movie piracy became a rampant issue on the Pulatec Web. Because legislation on digital copyright and piracy was slow to make its way through the bureaucracy of the Pulatec Union Legislative Assembly, Pulacan for much of the 2000s became something of an internet pirate's haven, with law enforcement utterly clueless as to the nature of the issue at hand and powerless to stop it. Sites like MajamBay hosted thousands of films and TV shows illegally, and action was only taken in 2008 when numerous media corporations lodged complaints against Pulacan via the Vespanian Exchange Institute. From then on, digital copyright law was delineated, but still poorly enforced. Even today, the onus is on server hosting services to actually take down offending websites. This change was still enough for international media corporations to return to full business procedures in Pulacan. In 2014, HMP and (insert international media corporation) signed a deal to create HuecaFlix, the first digital streaming platform to be based out of Pulacan. HuecaFlix was filled with digitally-remastered Pulatec shows and movies, some of which were from HMP's back catalog. In the latter part of the 2010s and early 2020s, numerous other streaming sites around the world have challenged HuecaFlix's hold on the Pulatec streaming market. Some, like X Service, digitize and collate old and avant-garde projects that were aired on pirate or local television stations or shown in arthouse movie theaters, but never picked up for mainstream distribution. Thanks to the prevalence of social media and streaming sites, the Internet has been gradually pulling away the younger generations of Pulacan from traditional services like movie theaters, television, and radio.

Cuisine

Hiero time

Sports

Sports hold a central place in Pulatec culture. Ceremonial games have been part of festivals in the country for centuries. Currently, the most popular spectator sports are baseball, combat sports, rugby, pitz, and motorsports. Of these, baseball is the most popular and considered the national sport. Various forms of ball-and-stick games have existed in both Nahua and Komontu cultures for centuries, but the introduction of large numbers of Nahua colonial soldiers and their form of sport in the 16th century to the Komontu is traditionally cited as the folkloric genesis of Pulatec baseball. Played traditionally alongside hip-and-ball games (akin to modern-day Pitz) at ritual occasions, professional baseball teams organized for commercial profit or purely secular enjoyment were relatively late innovations, arriving in the final years of the 19th century and early years of the 20th. Following the advent of mass communication in the first half of the 20th century, the popularity of watching organized sport exploded in Pulacan, and local sports teams began to attract significant local followings. Of these, then as now, baseball fans were notoriously fanatical. Imitating religious practices of deity mimicry, dedicated Pulatec sports fans may choose to dress up as a patron divinity on behalf of the team or adopt elaborate homemade costumes to show team spirit.