Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics: Difference between revisions

| Line 391: | Line 391: | ||

| [[file:IrvadistanURflag.png|50px]] [[Irvadistan]] | | [[file:IrvadistanURflag.png|50px]] [[Irvadistan]] | ||

| [[Qufeira]] | | [[Qufeira]] | ||

| | | 36,362,112 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[file:KhazestanURflag.png|50px]] [[Khazestan]] | | [[file:KhazestanURflag.png|50px]] [[Khazestan]] | ||

| [[Faidah]] | | [[Faidah]] | ||

| | | 43,776,680 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:NinevahURflag.png|50px]] [[Ninevah]] | | [[File:NinevahURflag.png|50px]] [[Ninevah]] | ||

| [[Adh Dhayd]] | | [[Adh Dhayd]] | ||

| | | 6,023,530 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[file:PardaranURflag.png|50px]] [[Pardaran]] | | [[file:PardaranURflag.png|50px]] [[Pardaran]] | ||

| [[Javanrud]] | | [[Javanrud]] | ||

| | | 104,552,103 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[file:RiyadhaURflag.png|50px]] [[Riyadha]] | | [[file:RiyadhaURflag.png|50px]] [[Riyadha]] | ||

| Line 415: | Line 415: | ||

! colspan="5" |[[Union Territory of Zorasan|Union Territory]] | ! colspan="5" |[[Union Territory of Zorasan|Union Territory]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:ZahedanUTCflag.png|50px]] [[Zahedan Union Capital Territory | | [[File:ZahedanUTCflag.png|50px]] [[Zahedan|Zahedan Union Capital Territory]] | ||

| [[Zahedan]] | | [[Zahedan]] | ||

| 18,557,230 | | 18,557,230 | ||

|- | |||

| [[File:Flag of the Khazal Islands UT.png|50px]] [[Khazal Islands|Khazal Islands Union Territory]] | |||

| [[Evazeh]] | |||

| 30,583 | |||

|- | |- | ||

! colspan="5" |[[Union Municipalities of Zorasan|Union Municipalities]] | ! colspan="5" |[[Union Municipalities of Zorasan|Union Municipalities]] | ||

Revision as of 16:58, 13 December 2020

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics اتحاد جماهیرعرفانی زرصانی Ettehād-ye Jamaheer-ye Erfāni-ye Zorasāni الاتحاد الجمهوريات العرفانية الكرصانية al-Ittiḥād al-Jumhūrīyyat al-Irfānīyyah al-Kurṣāniyyah | |

|---|---|

Motto:

National ideology: Sattarisim | |

Anthem:

| |

Great Seal | |

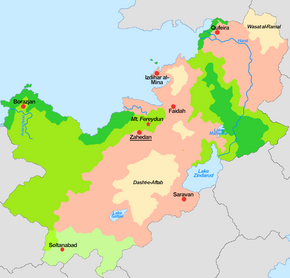

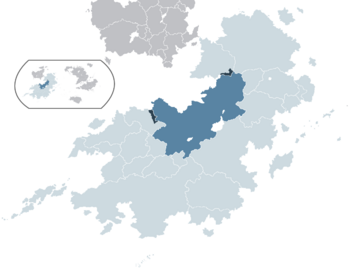

Zorasan in blue, Coius in light blue and claimed territories in dark blue | |

| Capital and largest city | Zahedan, UTC |

| Official languages | Rahelian Pardarian |

| Recognised regional languages | Kexri Syriati Yanogu |

| Ethnic groups | See Ethnicity |

| Religion | State religion: Irfan (Arta and Hasawi) Constitutionally recognised minority religions: Maronite Catholicism, Atuditism, Zoroastrianism, Druze |

| Demonym(s) | Zorasani |

| Government | De jure: Federal Sattarist parliamentary republic De facto: Federal dominant party authoritarian parliamentary republic subject to a civic-military system |

| Vahid Isfandiar | |

| Farzad Akbari | |

| Ibrahim Al-Fahim | |

| Legislature | Supreme Assembly |

| Superior Council | |

| Popular Council | |

| Establishment | |

| 31 October 1953 | |

• Constitution adopted | 4 November 1953 |

• Treaty of Unification | 22 May 1956 |

| 1974-1979 | |

| 11 January 1980 | |

• Current constitution | 10 May 1984 |

| Area | |

• Total | 4,692,920 km2 (1,811,950 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 1.3% |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 203,112,587 |

• 2012 census | 195,369,278 |

• Density | 36.88/km2 (95.5/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | estimate |

• Total | $2.639 trillion (13th) |

• Per capita | $12,997 |

| GDP (nominal) | estimate |

• Total | $1.919 trillion (9th) |

• Per capita | $9,450 |

| Gini | 34 medium |

| HDI | 0.784 high |

| Currency | Toman (₮) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Driving side | left |

The Union of Zorasani Irfanic Repulics (Pasdani: اتحاد جماهیرعرفانی زرصانی; Ettehād-ye Jamaheer-ye Erfāni-ye Zorasāni; Rahelian: الاتحاد الجمهوريات العرفانية الكرصانية; al-Ittiḥād al-Jumhūrīyyat al-Irfānīyyah al-Kurṣāniyyah), commonly called the Zorasani Union, Zorasan or the UZIR, is a federal constitutional parliamentary republic located in northern Coius. The UZIR is bordered by Xiaodong and Kumuso to the south, Ajahadya and Sinharia to the west, Tsabara to the east and the Gulf of Parishar to the north and Mazdan Sea to the north-west. The UZIR is home to diverse ethnic groups, with Arta Irfan as the majority and XXX as the largest minority, it also includes XX, Yazidis, XX and a tiny minority of Abburites. Its two largest ethnic groups are Pardarians and Arabs. With a population of 173.1 million it is the 3rd largest in Coius and the world, it has a total area of 4,692,920 km2 (1,811,946 sq mi), making it the 2nd largest in Coius and the 3rd largest in the world.

Zorasan is home to some of the world's oldest civilizations, beginning with the formation of the Asirani and Galdian kingdoms in the fourth millennium BCE. Both the Pardarian and Rahelian civilisations would be united under the former through the Barzanid Empire. The Sorsanid Empire would establish the tradition of Pardarian rule from the 4th century BCE until the 19th century, often with deep levels of Rahelian integration. The Arasanid Empire would emerge in the 3rd century CE as a world leading power, with territory stretching from Hydana to southern Bahia. The Arasanid Empire would be in regular conflict with both the Solarian and Verliquioan empires, until the emergence of Irfan in 620 CE and the Tagemes invasion .

The rise of Irfan between 620 and 690 succeeded the devastation of the Tagemes invasions, the fledgling religion overthrew the Arasanid Empire in the Emshab-ye Amorzesh, in which the Shah and his family were killed by rebels under Ardashir Fereydun. The empire was replaced with the First Heavenly Dominion, which rapidly expanded across northern Coius and Bahia in what became known as the Irfanic Conquests. From 690 CE to 1100 CE, much of northern Coius would be ruled under successive Heavenly Dominions sparking the Irfanic Golden Age, until the Fourth Heavenly Dominion transitioned to a monarchy under the Gorsanid dynasty.

For much of its history, the Gorsanid Empire would be a leading world power until it fell technologically and economically behind its Euclean rivals. Successive rebellions and crises would ultimately lead to the Gorsanid collapse and the eventual conquest of its territory by Euclean powers. In 1863, much of modern day Zorasan was colonised by Etruria and was subsequently divided into numerous colonial possessions, though the monarchy survived through the Etrurian-dominated Shahdom of Pardaran. During the first half of the 20th century Zorasan was dominated by numerous rebellions and uprisings against Etrurian rule which coincided with both the Great War (1928-1936) and Solarian War (1943-1946). Independence followed with Zorasan being divided into a series of unstable states along ethnic lines, where ideological extremism dominated politics. In 1949, Pardaran was unified following a short civil war under Mahrdad Ali Sattari, who's pan-Zorasani ideology led to a similar revolution in Khazestan in 1950 and the two nations merger. Over the next twenty years, conflict, terrorism and revolution would ultimately lead to Zorasani unification in wake of the Irvadistan War in 1979. Between 1979 and 1980, the new union reformed into a parliamentary non-partisan federation. Economic reforms led to significant economic growth and rapid development.

The UZIR is a member of the Community of Nations, GIFA, International Forum for Developing States and the ITO and a founding member of the Rongzhuo Strategic Protocol Organisation and Organisation for the Irfanic Community. It is recognised as a major power by international commentators; some have claimed that it is a potential superpower in the event of further economic development. The UNIR has the largest proven oil reserves and is the world's largest producer of oil and natural gas, leading it to be considered an energy superpower.

Etymology

The roots of the name Zorasan can be traced back to the Middle Pasdani "Xwarāsān", meaning "Land of the Sun." It was first used to denote the expanse of territories under the Arasanid Empire, when in 325 BCE, Shah Farrokhan II proclaimed his empire to be the "greatest expanse under the Sun" in a series of poems written in that year. His coining of the term was adopted by the First Heavenly Dominion during the Rise of Irfan, when the Prophet Ashavazdar, declared his intention to "free all Zorasan from the bounds of ignorance." The term from its inception until the Pardarian Civil War in the late 1940s, was rarely used to denote a singular polity, but rather a geographical region, under the Arasanids it denoted the imperial heartlands, which corresponded mostly to the modern bounderies of Zorasan, while under the Heavenly Dominions, "Zorasan" was used to denote the entirety of the Irfanic World, often due to the metaphorical comparison of the Sun to Khoda. Its relationship with the rise and spread of Irfan, alongside the definable boundries of Zorasan provided by the Shahs enabled the term to become culturally and political engrained in both the Pardarian and Rahelian peoples.

The use of "Zorasan" as a geographical term continued under the post-Dominion Pasdani empires and would see continued use by Etruria following the Conquest of Zorasan. The dismemberment of Gorsanid Zorasan in 1860 by the Etrurian colonial authorities saw "Zorasan" fall out of official use as the Etrurians sought to identify their colonial posessions independently of one another to deter a unified uprising. Between 1860 and 1946, the Etrurian colonies in Zorasan were collectively referred to as the "Southern Dominions" (Vespasian: Domini Meridionali), while the various underground anti-colonial movements maintained the use of Zorasan illicitly.

Following the de-colonisation of Zorasan in 1946, in wake of the Solarian War, the term's use fell exclusively to political figures in Pardaran, as the Rahelian states emerging out of the Etrurian colonies strove to secure independent national identities. However, the term Zorasan remained highly popular among the rural and urban poor classes, who saw Zorasan as a moniker for a pre-colonial time of prosperity, unity and independence. The Pardarian Civil War and rise of Renovationism in wake of the Khazi Revolution resulted in Zorasan's useage returning to the norm and was subject to considerable propaganda, fuelled by Pan-Zorasanism and Zorasani unification. The completion of unification in 1980 saw "Zorasan" be adopted as the official name of the unified country.

History

Pre-history

The earliest attested archaeological artifacts in Zorasan, like those excavated at Dorshad and Zarashfud, confirm a human presence in both Khazestan and Pardaran since 300,000 BC. Pardaran's Neanderthal artifacts from the Middle Paleolithic have been found mainly in the Miran region. From the 10th to the seventh millennium BC, early agricultural communities began to flourish in and around the Miran region in eastern Pardaran.

Pardarian development ran almost concurrently to the emergence of civilisations in the Asirani valley, in neighboring modern Khazestan. In Khazestan, the early Galdian civilisation became the source of what is debated to be the world's first writing system and recorded history itself were born. The Galdians are also argued to be the first to harness the wheel and create City States, and whose writings record the first evidence of Mathematics, Astronomy, Astrology, Written Law, Medicine and Organised religion. Writing systems also emerged in eastern Pardaran, with similar systems of cuneform to that of the Galdians.

Sorsanid Empire (550 BCE-400 BCE)

Arasanid Empire (400-322 BCE)

Rise of Irfan (322-300 BCE)

Heavenly Dominions (300-1100)

Gorsanid Empire (1100-1700)

Gorsanid collapse (1700-1880)

Colonial Zorasan (1880-1946)

Independence and Civil War (1946-1950)

Following the end of the Solarian War, the Treaty of Ashcombe restored independence to Etruria’s colonial possessions, establishing the independent states of Pardaran, Khazestan, Emirate of Irvadistan, Kexri Republic and the Confederation of Riyhadi Kingdoms. The use of the 1889 Treaty of Verlois to establish the borders, alongside the lack of legitimacy of the new governments resulted in the collapse of authority and government across swathes of Zorasan, and the emergence of warlord cliques, small statelets and two rival governments in Pardaran.

The Shahdom under Ahmad Reza Shah failed to establish control over the internationally recognised borders of Pardaran, owing to the Shahdom’s history as a compliant protectorate of Etruria since 1869. This allowed two military cliques and a nascent democratic republic to emerge in the north-west, while the Xiaodong-backed Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command; which had dominated the resistance movement during the Zorasani Rebellion (1936-1946) coalesced in the far-south. Competing ambitions eventually led to a multifaceted civil war that ultimately led to a PRRC victory over its rivals and the establishment of the Free Zorasani Republic in 1950.

In the Rahelian east of Zorasan, the Kingdoms of Khazestan and Irvadistan stabilised relatively quickly, with King Hussein I of Khazestan and King Said Ali of Irvadistan cooperating in confronting restive Rahelian tribes in the Al-Hizan region. Both kingdoms restored order and stability within their mandated borders by 1948, although economic crises and the spread of Pro-Sattarist elements in Khazestan would undermine the monarchy until its downfall in 1952. In the east, the Kexri Republic under its left-wing nationalist governnment sought to expand its borders at the expense of Rahelian, Druze and Yazidi tribes and local communities, culminating in the Kexri War (1946-1959). The various emirates and kingdoms of the Riyadha peninsula were the only states to stabilise immediately upon independence, coalescing into the Confederation of Riyhadi Kingdoms under the pro-Euclean Emir Rafiq Ali. Riyadha became a prominent safe haven for refugees and exiled writers, political thinkers and activists, who fled Pardaran toward the end of the civil war.

By 1950, the states forged by the Treaty of Ashcombe had established themselves, though the instability and anarchy of the four-year period produced a climate of intense revolutionary activity, ideological entrenchment and a deep divided between Pan-Zorasanism and nationalism. This divide would form the basis for the process of Zorasani Unification, as Pardaran and its Sattarist ideology expanded across Zorasan through revolution, coups and war.

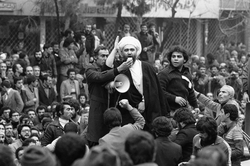

Unification of Zorasan (1950-1979)

The situation in Zorasan by 1950, though mostly stabilised politically, was still stricken by extensive war-time devastation, economic collapse, famine and shortages. The civil war in Pardaran saw extensive use of propaganda and radio by the PRRC leader, Mahrdad Ali Sattari who broadcasted daily, messages of republicanism, socialism, pan-Zorasanism and the threat of renewed colonialism. This broadcast were made across Zorasan, which led to the emergence of mass Sattarist movements in the Rahelian states. The failure by the new states to immediately confront the devastation caused by the Great and Solarian Wars had profound effects on their internal stability.

The PRRC immediately in wake of the civil war regularly vowed to unify Zorasan in order to birth a “renaissance” and to ensure that colonialism would never return to suppress the Zorasani peoples. The PRRC’s conflation of colonial exploitation with monarchism led to further agitation among the starving masses toward their monarchs in Khazestan and Irvadistan. This was defined by the power-struggle in wake of Mahrdad Ali Sattari's death in 1951 and his succession by Omid Sharifirad and then by Ali Sayyad Gharazi. The PRRC’s renewed focus on unification in wake of its victory in the Pardarian Civil War swiftly led conflict with its Rahelian neighbours.

Between 1950 and 1952, Khazestan was racked by mass bread riots, strikes and the continued effects of its collapsed infrastructure. King Hussein’s reliance on authoritarianism and often excessive violence to maintain control was capitalised by the Sattarist movement in Khazestan and its patron in Pardaran. On July 8 1952, a bread riot in the capital of Faidah escalated into a full-blow revolution, which coincided with a Pardarian military invasion. King Hussein was overthrown and executed, while Khazestan formally merged with Pardaran to form the Union of Khazestan-Pardaran, with Ali Sattari as Supreme Leader. However, the rapid disintegration of the Kingdom outpaced Pardarian armed forces, which resulted in northern Khazestan breaking away and forming the independent Emirate of Khazestan. The immediate deployment of armed units from the Emirate of Irvadistan, deterred a Pardarian advance, leading to the formal division of Khazestan for the next decade.

A cold war rapidly developed between the Union of Khazestan-Pardaran and the independent Rahelian states to the north. In the east, the left-wing Kexri Republic struggled to confront resistance from its Rahelian, Druze and Yazidi minorities, while it deferred from taking sides, it would eventually become a major theatre in the cold war. During the late 1950s, the region recoiled under the costs of terrorism, political agitation and economic mismanagement. The Rahelian states were faced with growing ideological extremes competing for control, while also threatening the ruling elites. The Emirate of Irvadistan, primarily focused on combatting Sattarism, failed to confront the socialist movement, which grew significantly from economic failures, inequality and weaknesses of the monarchy.

In 1962, a coalition of Rahelian, Druze and Yazidi rebel groups united to form the Revolutionary Resistance Command of Ninevah (RRCN). Aided by the UKP, it escalated its guerrilla war, while the UKP invaded the Kexri Republic in May 1962. An RRCN offensive on the Kexri capital of Surayda Hemko decapitated the Kexri government and the republic swiftly collapsed. A widely regarded rigged referendum six months later saw the former Kexri Republic merged into the UKP as the Region of Ninevah. This victory for the UKP greatly upset the balance of power and directly led to the Rahelian War in 1963. During the three-year conflict, the UKP would defeat the allied forces of Irvadistan, North Khazestan and the Riyhadi Confederation, and would see the reunification of Khazestan within the UKP.

The late 1960s and early 1970s would see repeated waves of terrorism, political instability, failed coups and agitation by both sides. The prior instability in Irvadistan coupled with the casualties and defeat in the Rahelian War led to the overthrow of the Emirate by the Irvadi Section of the Worker’s Internationale (ISWI) in 1968. The coup saw the collapse of the unified Rahelian opposition to the UKP, ultimately leading to the 1974 overthrow of the Riyhadi Confederation by the Revolutionary Resistance Command of Riyadha, this was followed by the admission of the Riyadha peninsula into the UKP, leaving Irvadistan as the sole remaining independent state.

Rising tensions coinciding with disputes over the Haradh oil field, led to the surprise Irvadi invasion of Khazestan in the Summer of 1975. The Irvadistan War, would devastate much of northern Zorasan and leave over a million dead. By 1978, facing chronic manpower shortages, collapsing industry and an advancing Khazi-Pardarian opponent, the Irvadi government collapsed. In 1979, the UKP captured the Irvadi capital of Qufeira and established the Provisional Revolutionary Government of Irvadistan. The PRGI worked tirelessly to prepare for the country’s admission into the UKP, while also confronting resistance and economic collapse. Despite the opposition, Irvadistan was admitted on January 11 1980, with the UKP becoming the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics, this marked the end of Zorasani unification and its completion.

Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics (1980-present)

Following the forming of the UZIR in 1980, the new Zorasani government faced considerable pressures for reform to consolidate unification. Many senior figures around Supreme Leader Javad Jahandar were concerned that the single-party state would perpetuate resistance and rebellion in Irvadistan and in other parts of the war-exhausted state. Jahandar opposed immediate reform, but ultimately agreed for considerable structural and constitutional change.

In 1981, Jahandar authorised the sitting of a Constituent Assembly to develop a new inclusive system, which would be introduced after a fixed period of continued single-party rule. By the start of 1982, the Assembly had produced the framework for a federal non-partisan parliamentary republic, which would provide universal suffrage, a commitment to human and civil rights and equally distribute powers to Union Republics to be forged out of the former states. The proposal was put to the Zorasani people by referendum on August 19 1982 and was backed by 88% of the electorate, the first democratic exercise in forty-years within Zorasan. The new constitution and government would be established in wake of a general election in 1985. Jahandar's intention to compete for office in 1985 was scrapped in wake of the 1983 Solarian Sea Crisis, a military confrontation with Halland, that resulted in a missile strike on a Hallandic naval vessel, and a surprise retaliatory airstrike on a major air base in northern Zorasan.

During this time and until the 1985 election, the single-party government under Javad Jahandar focused on reconstruction and the economic revitalisation of the northern regions. The merge of the Irvadi and UKP oil companies secured the new nation as the world’s largest oil producer and the possessor of the largest proven oil reserves. Aided by high prices, the government funded rapid reconstruction and modernisation, while also using its capital reserves to fund industrialisation and diversification. Despite the rate of reconstruction and economic growth, Irvadistan would see two unsuccessful revolts against the new government, with the Al-Thawra Uprising (1983-1984) and the Assan Uprising (1985). These failures saw the decline of Irvadi nationalism and resistance, further repressed by a mass embrace of the new semi-democratic system.

In 1985, Zorasan elected members to its local, state and federal level legislatures, marking the adoption of the 1981 constitution and the establishment of the non-partisan parliamentary system. The first parliament was stacked with Sattarist ideologues and figures from the now defunct Revolutionary Masses Party and the Zorasani Revolutionary Unification Front. Attallah Shahedeh was elected State President by the upper-house, while Assadollah Bakhtiar was re-elected First Minister following his appointment by the lower-house. Between 1985 and 1990, the Shahedeh-Bakhtiar administration continued its focus on reconstruction and economic reform, with the privatisation of state-owned enterprises, the opening of the economy to foreign investment and the formal replacement of the command-economy with state-capitalism as the national economic model. Economic growth averaged 7% annually during this period, while social reforms expanded education to every child, hundreds of schools and colleges were opened, new universities were opened to women and special scholarships were provided for war orphans. Healthcare also saw significant improvements, with new modern hospitals replacing antiquated or destroyed facilities in Irvadistan. Infant-mortality declined dramatically, and life expectancy rose from 64 on average to 69 by 1990. Mass inoculations eradicated many diseases that plagued pre-war Irvadistan. The same period saw living standards and wages rise nationally by a marked degree, an expansion in foreign trade and investment further improved infrastructure and non-petrochemical sectors of the economy.

These economic changes would be hastened in 1990 with the election of Abdelraouf Wazzan and Faris-Ali Erekat as State President and First Minister respectively. The new government was firmly within the pro-democratic reform camp, who sought to support economic reform with political liberalisation. Furthermore, they sought to further pushback the military out of governance of the nation, with the ultimate goal of dismantling the national security state. Between 1990 and 1995, the Wazzan-Erekat government successfully launched a major economic reform program, while steadily pushing back the military out of government affairs in exchange for concessions on military appointments and the defence budget. In 1992, they successfully secured the government's right to appoint the head of the Union Ministry for State Intelligence and Security (MSIS). Economic growth fell to 5% in 1990 owing to a oil price shock, before averaging 9% for the rest of the decade. Liberalisation also resulted in a significant cultural boom and renaissance, with modern expressions in art, music, theatre and film. The economic boom, coupled with the social and political opening up established the 1990s as the beginning of the Saffron Period. The 1995-1990 period marked the high point of the Saffron Period, where the country established close relations with several Asterian and Euclean states, rapidly boosting trade, economic development and foreign direct investment. In 2000, Ekrem Dalan and Izzat al-Din Kahala were elected into office, both sought a significantly deeper and wider liberalisation of Zorasan compared to their predecessors. AUSTERITY - MASS LAY OFFS - SECULARISATION - HYPER-PARTISANSHIP - HURRICANE - DEMISE OF SAFFRON PERIOD.

CHANWAN WAR - RETURN OF CIVIC-MILITARY SYSTEM - RETURN OF AUTHORITARIANISM - MORE ECONOMIC REFORM

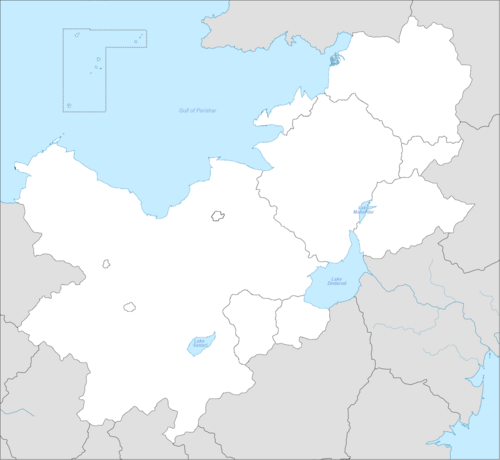

Geography

Zorasan is located in northern-central Coius and is one of the largest countries in the world, with a total area of 4,692,920 km2 (1,811,946 sq mi), the second largest in Coius after Xiaodong and the third largest in the world. To the north, Zorasan is bounded by the Gulf of Parishar and beyond by the Solarian Sea. The Gulf of Parishar is home to several small archipelagos, including the Khazal islands. Some sandbars have been built into sizeable islands through the use of dredging of the seabed, this includes Qabre Nakhoda island, some of these islands were constructed during the early 2010s as a result of Zorasan's government seeking to expand its exclusive economic zone. The coastal regions of north-west Zorasan are bounded by the Mazdan Sea. To the north-east, Zorasan borders Tsabara and Ihram, to the east it is bordered by Mabifia and Dezevau, to the south it is bordered by Kumuso, and Xiaodong through the Kharkestar Corridor. To the west, Zorasan borders Ajahadya and Sinharia.

The geography of Zorasan is divided into five distinct regions, the Great Steppe, the Tinnin-Gahvareh Region, which includes the Dasht-e Aftab desert, Gulistan of north-western Pardaran, the Sharezan Forests of Khazestan, Ninevah and Ajad and finally, the Irvadistan region. These five distinct regions also provide separate climates and biomes for fauna and flora.

The five regions are such:

- Great Steppe: The Great Coian Steppe, covers much of southwestern Zorasan and an estimated 15% of its total land area. The Zorasani region of the steppe is dominated by flat open grassland and shrubland and is sparsely populated. The northwestern region of the Zorasani steppe as it approaches the Gulistan, it transitions from grass and shrublands to forest steppe, with thicker seasonal growth interspersed by forests and woodland. The Steppe is shared with Zorasan’s neighbours, Sinharia, Kumuso, Ajahadya and Xiaodong. Zorasan and Xiaodong are connected via the Kharkestar Corridor.

- Gulistan: The Gulistan region of Zorasan dominates the entire north-west of Pardaran. Gulistan is a Pasdani word for “The Rose Garden”, named for the lush and thick forests and grass covered hills and valleys. The Gulistan region receives the second highest degree of precipitation after the Sharestan region.

- Tinnin-Gahvareh Region: The central regions of Pardaran and western Khazestan fall under this region. The Tinnin-Gahvareh Region contains three distinct regions in itself, the Gahvareh Basin, the Tinnin Plateau and the Dasht-e Aftab desert. The Gahvareh basin forms north of the Great Steppe as the elevation declines to several hundred feet above sealevel. The Basin contains Lake Sattari is a semi-desert biome, though its topography is relatively flat. East of the Basin is the Dasht-e Aftab, one of the world’s largest deserts and hosting the world’s largest salt flat. The Dasht-e Aftab also hosts the Darb-e Jahannam (Gate of Hell), where the temperature can reach 70.7 °C (159.3 °F) on average daily, during the height of the summer months. North of the Basin and Dasht-e Aftab is the Tinnin Plateau, which is an extension of the Steppe’s topography, running west-to-east. At the centre of the plateau is the Tinnin Mountain range, which hosts Mount Fereydun, Zorasan’s tallest peak, with a height of 5,609.2 m (18,403 ft). Despite the presence of the Dasht-e Aftab, the Tinnin-Gahvareh region is the most populous in Zorasan, being home to over 26 million people.

- Sharezan Forests: Running from south-to-north through the Union Republics of Ninevah, Ajad and northern Khazestan, the Sharezan Forests region is dominated by Varkanian mixed forests, created through the entrapment of humid air by the Dasht-e Aftab to the west and the Wasat al-Ramal desert to the north-east and the Fersi desert to the east. This region includes lush lowlands and montane forested areas and rolling green hills. This area owing to the entrapment of humid area, receives the highest precipitation in northern Coius.

- Irvadistan region: The Irvadistan region is divided into three sub-regions, the Coastal Forests, Semi-Desert interior and the Wasat al-Ramal desert. Northern Irvadistan shares the Ruqqad highlands with southern Tsabara. Irvadistan is also bisected by the Harat River, which finds its source in Lake Bakhtegan over 1,200km to the south. The Harat River valley, where over 70% of the population reside. Apart from the Harat Valley and the Parishar Gulf coast, the majority of the Irvadistan region’s landscape is desert, with a few oases scattered about. Winds create prolific sand dunes that peak at more than 30 metres (100 ft) high.

Climate

Owing to its unique biomes and geographical regions, the climatic nature of Zorasan is also markedly different from region to region. These differences range from arid and semi-arid to sub-tropical along the Pardarian coast, the Sharezan and Gilustan regions. Except for the Great Steppe and the Tinnin Plateau, no other region ever sees temperatures fall below freezing. The Gilustan and Sharezan regions remain humid for all seasons bar winter. Summer temperatures in these regions rarely exceed 30 °C. The Sharezan region sees an annual precipitation of 1,700mm (66.9 in) a year, while the Gilustan region sees only 680m (26.8in), this the same level for the western Pardarian and Irvadi coastal plains.

The Gahvareh Basin region, alongside southern and northern Khazestan and the Riyadhi peninsula are arid or semi-desert and are interspersed with desert. The Gahvareh Basin is also host to the Dasht-e Aftab desert. These regions see less than 200mm (7.9in) of rainfall annually and summer temperatures on average remain steady at 39 °C (102.2 °F). However, the Dasht-e Aftab can reach temperatures as high as 48 °C (118.4 °F), while the Darb-e Jahannam area of the desert has reached 70.7 °C (159.3 °F) on average for the past 20 years. These areas have very mild winters and very humid and hot summers, while in recent years, temperatures during winter have consistently remained above 15 °C (59 °F). The Tinnin Plateau on the otherhand experiences the lowest temperatures of all regions, with severe winters, heavy snowfall and temperatures regularly falling below zero. Spring and Summer for the Tinnin region are humid and warm.

Owing to the limited rainfall for most of the country, water scarcity has been described as the greatest crisis facing Zorasan in coming decades. Poor water management, overexploitation of aquifers and springs has had a severe detrimental affect on the distribution of water resources.

| Climate data for Zorasan, extremes since 1996 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 70.7 (159.3) |

52.3 (126.1) |

33.4 (92.1) |

30.3 (86.5) |

24.9 (76.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

24.9 (76.8) |

28.6 (83.5) |

33.1 (91.6) |

34.1 (93.4) |

35.8 (96.4) |

55.4 (131.7) |

44.3 (111.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −11.8 (10.8) |

−12.4 (9.7) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

2.5 (36.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

3.7 (38.7) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

−11.8 (10.8) |

−18.6 (−1.5) |

−12.1 (10.2) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

Biodiversity

Zorasan boast significant biodiversity both terrestrial and marine species, some of which are endemic solely to Zorasan present or historically. Terrestrial species present in Zorasan today include, foxes, gray wolves, bears, boars, wild pigs, jackals, lynxes and panthers. Non-predatory animals include water buffaloes, camels, mountain goats and Satrian Elephants, who were introduced to the forested north-west in the late 15th century. Zorasan was historically home to the largest population of Coiatic Cheetahs, which went extinct in the late 1990s according to the World Institute for Wildlife Protection. Zorasan is also home to populations of Pasdani Leopards and Gilustani Tigers, however, both these species are considered endangered and under serious threat of extinction by the 2030s. Avian species native to Zorasan include falcons, pheastants, eagles and Sparrowhawks.

The marine wildlife of Zorasan differs greatly, with the Gulf of Parishar being home to a wide variety of large mammals such as minke whales, humpback whales, bottle-nose dolphins and along the Harat Delta region, populations of dugongs have been recorded. The establishment of several Marine Life Protected Areas has enabled the return of a permanent population of hunchback dolphins. To the south, Lake Bakhtegan is home to a wide variety of freshwater fish, including large species of sturgeon. The presence of sturgeon stocks has resulted in Lake Bakhtegan being a major source for beluga caviar.

The situation regarding wildlife in Zorasan is ranked as one of the most serious to numerous NGOs and international charity groups. Over 80 species are on red lists for possible extinction. According to the WIWP, Zorasan has lost over 56% of its native wildlife since the early 20th century. Efforts by Zorasani state governments to regulate the protections of wildlife are regularly overridden by federal legislation that fast tracks the exploitation of mines and other subterranean resources without the input of Zorasan’s National Wildlife Institution or the Union Ministry for Environmental Protections. As of 2020, the final regulations demanding studies of local wildlife to assess the impact of human development was scrapped.

Environment

The natural environment in Zorasan has come under severe strain since the mid-20th century. The rapid development and industrialisation process beginning in the 1970s has caused irreparable damage to the natural world in some regions according to Zorasani and International environmentalist groups. The effect on wildlife has been profound with the loss of 56% of endemic species, while the country also faces water scarcity, poor air quality and rapidly expanding deserts, in what has been described as the “most severe case of desertification” in modern times.

Despite the wide consensus that climate change is playing a role in Zorasan’s environmental crises, most international and Zorasani groups agree that most of its crises are self-inflicted and man-made. The issue of water scarcity has been blamed on mismanagement of water resources and over-use by industry and agriculture. The over-development of agricultural land in limited space has in turn, played a key role in the instigation of desertification. Air quality worsens as the Zorasani government either disregards the need for regulation or active repeals what limited regulations are already in place.

Water scarcity

Water scarcity and shortages in Zorasan have become common in numerous regions in recent years. The lack of water access is regarded as the most serious environmental issue facing Zorasan. Between 2010 and 2020, over 36.4 million people went without clean drinking water 8 out of the 10 summers, with many reservoirs being emptied by usage within weeks of the summer season beginning. Approximately 6.5 million Zorasanis do not access to clean drinking water all year round and rely on government subsidised bottled water for personal usage. A vast majority of these cases are in southern Pardaran, specifically, the southernmost provinces of Pardaran, and the Union Republics of Armavand and Saravan.

In 2018, the Community of Nations launched a study and detailed that the root causes of these regional shortages were the diverting of what limited water resources the regions had to fuel industry, agriculture and the largest urban areas. Approximately 28% of the south’s natural water is diverted to Zahedan and its 18 million citizens. One of the starkest examples of the south’s problem is the decline of Lake Sattari. The lake since 1980 has lost over 60% of its water, due to both limited precipitation but also over-development. Between 1981 and 1984, six large pump stations and irrigation systems were constructed to support local agriculture, while no significant effort was made to educate farmers on water use. In 1991, a further irrigation system was constructed to supply the rapidly growing city of Soltanabad with drinking water and for industrial use.

In 2018, the CN report said, “little attention paid to the need of sustainability has led to over 35 million people facing the prospect of daily water shortages. Over-development of limited water resources has seen what is produced supply millions, but without any regard to the need to regulate to sustain.”

Desertification

Ever since the onset of the green revolution in Zorasan during the 1960s and 70s, agriculture alongside heavy industry has been subject to sizeable state investment and subsidy. With the support of the petrochemical industry, the Zorasani government throughout the 1980s constructed one of the largest irrigation systems in the world, transforming large parts of the Tinnin Plateau and Gahvareh Basin into productive and profitable farming regions. By 1998, Zorasan became self-sufficient for its food production.

However, the over development of limited areas, has led to significant cases of overgrazing and deforestation. The systematic destruction of the Sharezan Forest and overgrazing in the Gahvareh Basin has led to the expansion of the Dasht-e Aftab northward and eastward. Since the early 2000s, the Dasht-e Aftab has grown by 2,300km². Deforestation and overgrazing in northern Khazestan has been blamed for the 36% increase in the land area of the Al-Nifayat al-Shamaliya desert near the Riyadhi border. The issue of desertification has been worsened by the growing issues surrounding water scarcity, especially in the Gahvareh Basin, where most water resources are consumed by the industrial hubs of Zahedan, Irfanshahr and Ineqlabshahr.

In 2018, the Zorasani government announced a €10.5 billion program dedicated to combatting the desertification of the Dasht-e Aftab and Al-Nifayat al-Shamaliya deserts. The same year, the government admitted that desertification endangered the livelihoods of millions.

Pollution

Air quality in Zorasan has consistently ranked as among the most unclean and unsafe since the 1980s. Zahedan, Borazjan, Faidah, Qufeira and Soltanabad have ranked among the top 15 most polluted cities in the world since 2000. Zahedan has ranked as the most polluted city in Zorasan since records began in 1990, owing to its geographical location, Zahedan’s smog from street traffic and industry becomes trapped beneath hot air blocked by the Tinnin Mountains from being blown north by prevailing winds. The Khazi state capital of Faidah has ranked as the second most polluted city owing to the presence of large petrochemical industries, notably the Said Khadir Refinery. Air pollution in Zorasan is estimated to cause over 260,000 premature deaths a year.

While air pollution has been regularly considered a major threat, environmentalist groups have also criticised the degradation of marine environments by pollution. Zorasan’s limited number of rivers has brought to public attention the issues relating to urban wastewater, industrial and chemical run-off and the dumping of untreated human waste into rivers, streams and canals. Oil and chemical spills along the Harat River have caused serious damage both to water quality and marine wildlife, while stretches of the Parishar Gulf coast have been subject to both oil spills and the depositing of chemical and industrial run-off. In 2003, over 80% of the Kajur River’s aquatic wildlife was killed following the leakage of 100,000 tons of cyanide-contaminated water from a industrial chemicals plant in Javanrud. It remains the worst environmental disaster in Zorasan since 1990.

Government and politics

Zorasan is a federal, Sattarist, parliamentary republic. Zorasan’s political system operates under a framework laid out in the 2008 constitution known as the Second Treaty of Union (Ertegha-Ettehad). Amendments generally require a two-thirds majority of both the Popular Assembly and the Superior Assembly; the fundamental principles of the constitution, as expressed in the articles guaranteeing human dignity, the role of Irfan, the federal structure, and the rule of law are valid in perpetuity.

The Zorasani political system provides significant power and influence to the armed forces, through the Central Command Council. The CCC has the right to appoint key cabinet positions, holds vetoes over select areas of government responsibility and vets parliamentary candidates for the state and federal level, while also maintaining a two-thirds majority in the upper-house through its political grouping, Zorasan Zindebad.

The Zorasani government is classified as a “civic-military hybrid regime”, while also being classified as “authoritarian.” Zorasan has long been a serious violator of human rights, being regularly criticised and condemned.

Government

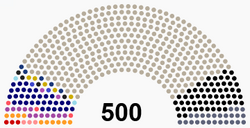

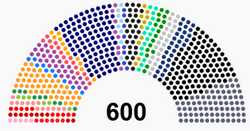

|

|

Government: Society for Justice and Development (57) Association for the Preservation of the Union (25) Zorasani People's Party (5) Association of Patriotic Clerics and Seminarians (5) Supported by: Zorasan Eternal (4) Irfanic Workers House (2) Union Association of Mothers (2) Union Association of Veterans and the Martyred (2) Opposition: People's Society for Freedom and Prosperity (32) Tradition and Moderation (12) People's Democratic Union (3) National Platform for Reform (10) Liberty and Unity (3) United Party of the Socialist Left (3) Armed Forces Zorasan Zidebad (335) |

The head of state is the State President who is elected by the upper-house of parliament for a five-year term. The State President is invested with some executive power, but is mostly restricted to a ceremonial position. The State President has the power to dissolve parliament, appoint or dismiss federal ministers, state governors, diplomatic and civil service officials. The State President de-jure chairs the Central Command Council, which is also technically the National Security Council of the Zorasani government. However, the commander-in-chief of the Zorasani Irfanic Revolutionary Army chairs the CCC in reality.

The First Minister is appointed by the members of the Popular Assembly by simple majority vote. The first minister is assisted by the Council of Ministers, whose members are appointed by the State President on the advice of the First Minister. The Central Command Council also appoints members of the Council of Ministers, who cannot be removed by either the State President or First Minister. The Council of Ministers comprises the ministers, ministers of state, and advisers. Between 1980 and 1995, there were over thirty-five cabinet positions, but was reduced to merely twelve in 1995 as the state administrations were granted significantly more autonomy. From 2008 onward, this process of de-centralisation has been reversed and the states have been stripped of much of their original power. As of 2019, there are twenty-two cabinet positons.

On the other hand, the Zorasani military plays a significant role in the national executive. The Commander-in-chief of the Zorasani Irfanic Revolutionary Army de-facto chairs the Central Command Council, a senior body consisting of sixteen commanders from all branches of the military. The Central Command Council is also the executive's national security council. The CCC has theright to appoint two-thirds of members of the Superior Assembly (the upper-house), by doing so, any attempt to reform the 2008 constitution would require military support to secure the necessary two-thirds majority to pass. The CCC also appoints 10% of members of the Popular Assembly (lower-house), this coincides with the CCC's ability to vet all parliamentary candidates through the National Commission for Political and Social Matters, which also includes members of the Irfanic clerical establishment. Military officers who reach the rank of Brigadier General and above, receive seats in the upper-house for life.

Most pivotally, the CCC appoints the Foreign Minister, the Internal Affairs Minister, State Intelligence and Security Minister and the National Defence Minister. These appointees cannot be dismissed or removed by either the First Minister or State President. Collectively, this grants the military control over foreign policy, law enforcement, domestic and external intelligence. The Central Command Council has a veto over all legislation related to these areas.

Legislature

The legislature of Zorasan, known as the Supreme Assembly of the Union, is a bicameral body, and is comprised of the 500-member upper-house Superior Council, and the 600-member lower-house Popular Council. The Popular Council is the sovereign national body. Members of the Popular Assembly are elected through the open list proportional representation under universal adult suffrage to single-member constituencies.

The Superior Council is unique in that two-thirds of its members (335) are appointed by the Central Command Council, while members who hold the rank of brigadier general or above hold seats for life. This guarantees any government effort to amend the constitution, would require the assistance and support of the armed forces. The remaining 165 members are elected by universal suffrage, with each administrative division of Zorasan providing 15 members.

Members of the Popular Council are elected by universal adult suffrage (eighteen years of age.). Seats are allocated to each of the eight Union Republics, two Union Municipalities and the Union Territory on the basis of population. Popular Council members serve for the parliamentary term, which is five years, unless they die or resign sooner, or unless the Popular Assembly is Council. Owing to Zorasan's unique political culture, there are 24 political parties represented in the Popular Council, though all with the notable exception of Zorasan Eternal and the groupings representing "societal sectors" are aligned with umbrella electoral alliances. As of 2019, these electoral alliances were True Way, Alliance for Moderation and Fairness, Coalition for the Zorasani Dawn and the People's Front for Socialism and Equality. These alliances align the specific ideological groupings of member-states, with True Way representing the right-wing, Irfanic, nationalist Neo-Sattarist platform, the AMF, centre-right and centrist, CZD representing the centre-left and the PFSE representing the far-left. It is rare for parties to leave their respective electoral alliance, though political affiliation of individual members is known to fluctuate. Since 2005, True Way with the support of independent parties has held a majority in the Popular Council and been in government as a result since.

The Popular Council, Zorasan's sovereign legislative body, makes laws for the federation under powers spelled out in the federal legislative List and also for subjects in the concurrent List, as given in the fourth article of the Constitution. Through debates, adjournment motions, question hour, and standing committees, the Popular Council keeps a check on the government. It ensures that the government functions within the parameters set out in the Constitution, and does not violate the people's fundamental rights. The Supreme Assembly collectively scrutinizes public spending and exercises control of expenditure incurred by the government through the work of the relevant standing committees. The military is further empowered by the Central Command Council holding the responsibility to vet parliamentary candidates for both houses of the Assembly. It does this through the General Directorate for Political and Social Affairs.

Law

Administrative divisions

The Union comprises seven federal states which are collectively referred to as Union Republics (Ettehād-ye Jamaheer). Each state has its own state constitution, and is largely autonomous in regard to its internal organisation. Further to the seven states is the single Union Territory (Ettehād-ye Azar), in the form of the Zahedan Union Capital Territory, which is the self-governing national capital. The Union is also comprised of two municipalities (bāladiyyeh), the holy cities of Ardakan and Namrin, which hold some autonomy from the federal government. Every administrative division is led by an elected governor (ostāndār), who is appointed by the divion's legislature.

Despite the differences in size and population of the union republics, each is divided in 24 provinces (ostān), there are 168 provinces in the Union. The provinces are divided into counties (šahrestān), and subdivided into districts (baxš) and sub-districts (dehestān).

| Map | Name and flag | Administrative centre | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Union Republics | |||||

| Saravan | 3,100,068 | ||||

| Khiyara | 1,112,547 | ||||

| Qufeira | 36,362,112 | ||||

| Faidah | 43,776,680 | ||||

| Adh Dhayd | 6,023,530 | ||||

| Javanrud | 104,552,103 | ||||

| At-Turbah | 7,526,197 | ||||

| Karandagh | 3,447,480 | ||||

| Union Territory | |||||

| Zahedan | 18,557,230 | ||||

| Evazeh | 30,583 | ||||

| Union Municipalities | |||||

| Namrin | 2,102,482 | ||||

| Ardakan | 2,883,687 | ||||

Foreign policy

The official goal of the government of Zorosan is to establish a new world order based on world peace, global collective security, and international equality. Since the time of the Irvadistan War, Zorasan's foreign relations have often been portrayed as being based on four strategic principles; eliminating outside influences in the immediate region, maintaining Zorasan as the leading power of northern Coius, securing Zorasani unification and pursuing extensive diplomatic contacts with developing and non-aligned countries, primarily in wider Coius-Bahia.

Zorasan is a member of the Community of Nations, GIFA, NAC and the ITO.

Zorasan's closest relations are with Xiaodong, although the nature of these close relations differ. In regards to Xiaodong, following the Corrective Revolution when XXX met Mahrdad Ali Sattari in 1957 both countries began to foster close political and economic ties as both countries were ruled by one-party governments intent on regional hegemony. Close cooperation between both governments became more prominent under Sun Yuting and Ghassan Ali Ghaddar, and have since Evren Volkan and Yuan Xiannian held office seen a dramatic revival of ties. The government of Xi Yao-tong has furthered this policy, signing significant trade deals with Zorasan in 2016 and 2017, and an increase in military cooperation. Zorasan meanwhile has provided military and technological cooperation with Xiaodong, most prominently during the Third Duljunese-Xiaodongese War. The extremely close and friendly relations between Xiaodong and Zorasan has been called the Rongzhuo-Zahedan Axis.

Armed Forces

The Zorasani Irfanic Revolutionary Army (Arteš-e Enghelâb-e Zorasāni-e Erfāni) consists of the Land Forces, the Navy and the Air Force. The fifth branch exists, which is held by the National Protection Force which exists as a mostly paramilitary force. The Zorasani Irfanic Revolutionary Army currently has around 3,712,000 troops overall (761,000 active, 2,951,000 in reserve, including 367,664 paramilitary soldiers), making it overall the Xth largest in the world

The State President of the Union is the commander-in-chief of the Zorasani Irfanic Revolutionary Army, which answers to the State Council of Ministers via Ministry of National Defence (MoND), which is headed always, by the Chief of Staff of the Zorasani Irfanic Revolutionary Army. Military affairs are primarily handled by the Supreme Revolutionary Military Command, a forum of military commanders who nominally subordinate to the State Council of Ministers. Since the Arduous Revolution, the military has played a significant and domineering role in national politics.

The coast guard and gendarmerie and police forces take on military functions - in the event of war, but are subordinate to the Ministry of State Security. The main intelligence unit, the General Intelligence Directorate (Resat-e Ejmal-e Ettela'at; RESAT), also is officially part of the military structure however they report directly to the government via the Ministry of National Defence. Despite its role as the military intelligence agency, it enjoys a significantly greater role in federal intelligence activities than the State Security Service (Ta'min-e Ejbaree-e Dowlat; TEJDO).

The Zorasani Irfanic Revolutionary Army has gone through numerous periods of modernisation and reform to maintain a dominant position within northern Coius; known as the Union First (Ebteda'Ettehād) policy, allowing it remain relatively as the most disciplined, well armed and capable forces in Coius; this has meant either great efforts being made in domestic R&D or the purchase of quality equipment and systems from foreign producers.

It is widely accepted that Zorasan operates an extensive chemical weapons arsenal, with an estimated combined total of over 14,000 tons of chemical agents in storage.

Conscription - known as "Patriotic and Revolutionary Duty" (Takleef Enghelabee-parast) is currently enforced for all male citizens between the ages of 18-21 for a period of a year to three years, dependent on education and job location. Zorasan does not recognise conscientious objection and does not offer a civilian alternative to military service, many conscientious objectors are either imprisoned under charges of "conspiring against the state" or press-ganged into four year service.

The armed forces are subject to controversial accusations of abuse and harsh treatment of trainee soldiers; with the use of beatings, caning and lashing in punishment of poor behaviour, low enthusiasm and slow progress in improvements. The IRA is also known to train its forces in "Isolated Desert Deployment"; in that units of troops are airdropped into the desert, with limited food and water to develop resilience in the event of being trapped or stranded in hostile environments seen in Coius.

Human rights

Zorasan has been consistently criticised internally and abroad, with human right monitoring organisations such as the International Council for Democracy as of 2017 ranking the Union as unfree. The ICD stated "Zorasan remains a fundamentally flawed parliamentary democracy, with overbearing control by the unaccountable and unelected clergy and military controlled bodies. The mass surveillance and censorship system remains in place and undermines freedom of speech and the press. The excessive use of capital punishment, torture, rape and false imprisonment also remains rampant."

Zorasan's situation is unique in that the systematic abuses of human rights is conducted outside government control and oversight. The ICD has noted that much of the repressive policies and activities are conducted by the military, rather than the federal government. The military's oversized control of state media and the use of the General Intelligence Directorate (RESAT) to pursue activists, civil rights lawyers and critics of the state, led the ICD and the Euclean Community in 2018 to note, "without confrontation of the deep-state within the UZIR, it is unlikely that human rights will improve in the medium to long term."

Economy

As of 2019, Zorasan had the 9th largest economy by GDP nominal, with $1.809 trillion and the 13th largest economy by GDP PPP with $2.250 trillion. The Global Institute for Fiscal Affairs classifies Zorasan as a newly industrialised nation and a middle-income economy. The country operates an economic model many have described as state capitalist, with heavy state intervention and ownership alongside private businesses. Following initial pro-market reforms beginning 1985 and more expansive reforms throughout the 1990s, the Zorasani economy became one of the fastest growing in the developing world, with GDP growth remaining above 6 percent from 1991 to 2001, before growing consistently above 8 percent from 2009 onward. The most prominent sectors of the Zorasani economy are Industry, 41.45%, petrochemicals 29.5%, services 25% and agriculture 4.05%.

Since 1980, the structure and nature of the economy has changed considerably. Upon the Union's founding 1980, its newly unified economy was dominated by agriculture and petrochemicals, owing to both the reliance on petrochemicals for revenue of pre-unification states and their shared aims of promoting agricultural self-sufficiency. The degree of development varied between the states, though all were historically recognised as rentier economies. Following the completion of unification and the inescapable need to rebuild entire regions owing to near thirty-years of warfare saw a significant shift in economic planning and strategy. In 1980, the Zorasani government recognised the limitations of oil-dependency and sought to dramatically diversify the economy, both as a means of escaping rentier status and to provide greater means of improved living standards for the entire population. Throughout the 1980s, high oil prices and the consolidation of the unified oil industries - turning Zorasan into the largest producer of petrochemicals in the world, supplied the government with the necessary capital to invest into manufacturing and services. The industrialisation process was aided by urbanisation, which further fuelled diverisification and infrastructure development. Progress continued throughout the 1990s, during which the GDP rose at an average rate of 9.1%. As a result, the official poverty rate fell from 60% to 15%. Reduction of trade barriers from the mid-1990s made the economy more globally integrated. A series of pro-market reforms in the late 1990s expanded competitiveness and hastened diversification, however, more radical reforms in the early 2000s caused a sharp economic shock, combined with privatisation of ineffecient state owned enterprises threw the economy into recession, which was deepened by the onset of the 2005 Global Recession. Political instability between 2005 and 2006 slowed recovery, before growth returned to its 9% average in 2007, which has been maintained since.

Today, the diversification has been widely praised and documented by leading global economists. Zorasan is one of the largest producers of steel, industrial and electrical parts and its shipbuilding industry is one of the fastest growing, while it has also established itself as one of the larger shipbreakers. Zorasan is the leading economy in Irfanic Finance, it has risen to be one of the largest producer textiles, with an estimated 1.9 million workers in the textile industry alone. Zorasan has abundant natural resources like oil and natural gas, coal, copper, gold, bauxite and aluminium, while agriculture produces fruits, nuts, flowers and rice. However, with the exception of oil and natural gas, the most prominent exports are manufactured goods; textiles, electronics, electronic parts, industrial equipment, steel and chemicals. In recent years, Zorasan's automotive and locomotive industries have grown to boast some of the largest producers, with Zorasan ranking as the 3rd largest producer of city buses and coaches and the 5th largest producer of locomotives and high-speed train units. Xiaodong, the Euclean Community, Ajahadya are Zorasan's largest trading partners. The country's armed forces are unique in that it owns and operates a sizeable business empire in its own right, according to the Global Institute for Fiscal Affairs, the Zorasani military owns or holds significant voting shares in twelve of the largest Zorasani companies, which it manages through the Great Soldier Foundation holding company.

Energy

Zorasan has the world's largest proved oil reserves, with an estimated 354,103,000 barrels, it is also the world's largest producer. Zorasan also ranks XX in proven natural gas reserves, with 15.3 trillion cubic meters and is the Xth largest producer. It is LOPS's largest oil producer and is widely considered to be the pre-eminent energy superpower. As of 2019, Zorasan's production of oil averaged 11.55 million barrels per day (XXX m3/d), a marked increase from the average of 6.8 million barrels throughout the 2000s. Zorasan spends €5.5 billion on maintainence, research and development and modernisation within its oil industry, while a further €3.5 billion is spent on exploratory wells, expansion of existing wells and improving extraction processes. 111 exploratory wells were drilled between 2005 and 2008. Between 2006 and 2012, Zorasan spent €1 billion on developing clearner fuels.

The country's long held program for diversification from oil-reliance, while not dimimishing the country's production or output has resulted in the establishment of alternative energy sources. The country is one of the largest consumers of coal in Coius and operates an estimated 26 coal and gas-fired power stations. In 2000, the Zorasani government announced plans to reduce domestic oil use by 35% by 2030, this included plans for the full-adoption of solar, geothermal, hydroelectricity and wind power. Between 2003 and 2005, significant reforms to the country's long-time ineffecient and fraudulent energy subisidies succeeded in reducing domestic use of fuel. In 2003, the country's fourth nuclear power plant was activated at Qufeira, Irvadistan. In 2016, the world's second largest solar farm was opened near Kashdar in central Pardaran, the Kashdar Solar Park produces 850 MWp of energy. The rapid development of various dam projects, while increasing non-oil energy, has had a serious and adverse effect on the country's water supply, exacberating the Zorasani water crisis.

Tourism

Science and technology

STRDC is the leading agency for developing science, technology and innovation policies in Zorasan. STRDC is the umbrella semi-autonomous government agency charged with overseeing and directing scientific studies and activities in Zorasan and is subordinate to the Union Ministry for Science and Technological Development and under some oversight by the Central Command Council. STRDC directs both state agencies and private research and development bodies. Among STRDC's major subordinate bodies is the Zorasani Space Research Organisation, the country's official space agency. Supporting to the ZSRO is Zorasani Aerospace and Atmospheric Industries (ZAAI), which plays a pivotal role in the development and production of satellites, including a series of global observation satellites for reconaissance. ZAAI has been the most prominent producer of satellites launched by ZSRO for commercial, military and scientific purposes.

Zorasan ranks amongst the top 10 for number of university graduates and the top 5 for doctorate degrees, primarily in medicine, engineering and physics. The country operates over 100 universities and 26 academies, the most presitigous include the Abdolreza Mandarani University, the Mazdavand Medical University and the Faidah Metropolitan University for Disease.

Zorasan also hosts several of the largest pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, in 2007, Zorasani scientists at the Imam Ardashir Centre for Life Studies successfully coloned a sheep by somatic cell nuclear transfer. A study in 2010 by the International Council for Bio-Medicine, found that stem cell research in Zorasan is amongst the top 5 in the world. Zorasan also scores high in rankings of nanotechnologies. Zorasan's history in medical research has produced several breakthroughs, including the collaborative success in inventing and developing the first artificial cardiac pump, the precursor of the artificial heart.

The Zorasani nuclear program was launched in the 1970s. Zorasan became the Xth country to produce uranium hexafluoride in 1990, and controls the entire nuclear fuel cycle.

Infrastructure

As of 2018, there were 104 airports in Zorasan, including 24 international airports. The most busiest in the country, Zahedan Mahrdad Ali Sattari Airport is the 10th busiest in the world, serving 39,569,204 passengers between January July 2017. Plans for a new and third international airport of Zahedan will see it become one of the more busier in the world, with a capacity to serve 165 million passengers per year. Air Zorasan is the flag carrier and serves the country alongside other national carriers. As of 2020, there are plans a 18 new regional airports to link the less developed frontier regions with the highly urbanised coast.

As of 2018, the country has a roadway network of 115,888 kilometres (72,09 miles). The total length of the rail network was 19,991 kilometres (12,421 miles) in 2017, including 6,133 kilometres (3,810 miles) of electrified and 1,457 kilometres (905 miles) of high-speed track. The Union General Railways started building high-speed rail lines in 2001. The Zahedan-Faidah line became operational in 2008, while the Faidah-Qufeira line entered service in 2015. In 2018, the Zahedan-Karandagh-Saravan line became operational, followed in 2019 by the Zahedan-Mazdavand line. Construction of the Faidah-Ad Dayhd and the Qufeira-Khiyara lines are on scheduel for completion in 2023 and 2024 respectively. The most ambitious high-speed rail line under construction of the Zahedan-Rongzhuo line, which will travel an estimated 1,100 miles through the Kharkestar Corridor, to connect two of the largest cities in the world. The line is estimated to be completed by 2026. Zorasan also boasts several of the largest ports in the world, with Bandar-e Parvadeh being the second largest on the Solarian Sea after Accadia. Other majors ports include Bandar-e Hussein, Safwan and Chaboksar.

Many natural gas and oil pipelines span the country's territory. The Kharkestar Stream pipline, the second longest oil pipeline in the world, was inaugurated on 3 May 2002 and serves to export Zorasani petrochemicals to Kumuso and Xiaodong, the Ajad Stream pipeline serves Southeastern Coius and the Mabifia-Extension pipeline connects Zorasan to Bahia, but also permits the reselling of Mabifian oil and gas to Euclea. Plans for the Solarian Stream pipeline, connecting Zorasan to southern Euclea through Galenia and Etruria has been hold since 2016.

Zorasan's internet, which has 100.3 million active users, holds a 'Not Free' ranking in Liberty House's index. Zorasan's government has constantly blocked websites such as social media sites, news sites and online educational wikis. According to some references, Zorasan is the leading nation in social media censorship. The internet in Zorasan has been known to be used as a tool for repression, both through the spread of misinformation, propaganda and its uses a trap for dissidents and critics of the regime.

Demographics

In the 2012 census according to the Centre for Union Statistics, the national population stood at 195.36 million, and population growth stood at 2.11% annually. Over 70% of the population lived in towns and cities, one of the lowest rates of urbanisation for a major world economy. In 2019, the Centre for Union Statistics, using its Address Registration System estimated that the population was 203 million. Zorasan has an average population density of 36.88/k m² (95.5/sq mi). Zorasan has the third largest population in Coius and the world.

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1952 | 68,771,235 | — |

| 1962 | 84,987,800 | +23.6% |

| 1972 | 99,319,245 | +16.9% |

| 1977 | 119,148,530 | +20.0% |

| 1982 | 138,511,477 | +16.3% |

| 1987 | 159,484,374 | +15.1% |

| 1992 | 170,912,654 | +7.2% |

| 1997 | 178,490,409 | +4.4% |

| 2002 | 184,023,257 | +3.1% |

| 2007 | 189,506,381 | +3.0% |

| 2012 | 195,369,278 | +3.1% |

| 2017 | 199,965,841 | +2.4% |

| 2020 | 203,112,587 | +1.6% |

| Source: UKP census (1952-1972) UZIR census and estimates (1972-present) | ||

The 2012 census broke down the population by age group, with people within the 15–64 age group constitute 67.4 percent of the total population; the 0–14 age group corresponds to 25.3 percent; while senior citizens aged 65 years or older make up 7.3 percent, this gives Zorasan one of the youngest populations in the world. In 1980, when the first official census was recorded in the Union (following the annexation of Irvadistan), the population was 68.77 million. The largest city in the union, Zahedan, is also 3rd largest in population and size in Coius.

Zorasan does not officially recognise ethnicity, as per Article 89 of the Articles of Unification, which defines a “Zorasani” as “anyone bound to the Union through the bond of citizenship or the right of birth.” Owing to Zorasan’s multi-ethnic nature, the term “Zorasani” is the legal term for citizens of Zorasan and does not hold any ethnic definition. The active opposition to ethnic identities has led to a considerable limitation on studies aiming to identify the ethnic disposition of the Zorasani population, the lack of ethnic options in regard to the census no reliable data exists. However, it is estimated that 40-45% of the population is Pardarian and 30-35% are Rahelian. 8-10% of the population are Kexri and the remainder of comprised of numerous ethnic minorities. Some estimate that there over 20 ethnic groups present in Zorasan, including Chanwans, Bahio-Pardarians, Bahio-Rahelians, Syriazi and Atudites. As a consequence of the unrecognition of ethnicity, the term "minority" is a recurrent sensitive issue in Zorasan, especially in view of Zorasan's treatment of its minorities. The Chanwan minority is one particularly effect group, owing to the Zorasani view that they are not a "traditional people of Zorasan." Their Xiaondongese origins coupled with their non-Irfanic status often leads to discrimination both state and non-state.

Zorasan is officially a bi-lingual state, with Pasdani and Rahelian as the two official languages of the country. Both languages are present in politics, business and everyday life and are often used interchangeably by Zorasanis, however, Pasdani takes predominance as the lingua gaullica in government affairs. All official government documentation and publications are printed in both languages. Newspapers and public broadcasters provide separate publications or broadcasts in the respective languages. The two official languages are taught simultaneously at every year of education, while language tests for educational advancement are mandatory. As of 2018, an estimated 92% of Zorasanis speak both languages fluently.

Minority languages are not recognised by the Zorasani government, though some states do provide protection for their use. Irvadistan for example, provides protections for Syriazi and Pardaran provides protection for Lashkari.

| Rank | Province | Pop. | Rank | Province | Pop. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Zahedan  Borazjan |

1 | Zahedan | Zahedan-takht | 18,557,230 | 11 | Ardakan | Aqda | 970,611 |  Javanrud  Faidah |

| 2 | Borazjan | Ashkezar | 9,573,217 | 12 | Gamsar | Shahrud | 803,852 | ||

| 3 | Javanrud | Ardestan | 4,932,075 | 13 | Shul Abad | Delfan | 776,802 | ||

| 4 | Faidah | Qarqur | 3,403,919 | 14 | Tarim | Hajjah | 543,127 | ||

| 5 | Bandar-e Parvadeh | Bushkan | 3,157,120 | 15 | Oshtorinan | Basht | 541,111 | ||

| 6 | Izdihar al-Mina | Izdihar | 2,110,343 | 16 | Pataveh | Ashkezar | 490,536 | ||

| 7 | Ad-Daydh | Zabdah | 2,501,332 | 17 | Qush Teppa | Teppah | 436,002 | ||

| 8 | Soltanabad | Khvansar | 1,855,375 | 18 | Bandar-e-Khamir | Dorestan | 399,110 | ||

| 9 | Qeydar | Tarut | 1,813,997 | 19 | At-Turbah | Khamr | 300,019 | ||

| 10 | Qufeira | Raydah | 1,711,000 | 20 | Namin | Tazeh-Kand | 274,358 | ||

Languages

Zorasan is a multi-ethnic and multi-lingual state, though it only recognises two languages, Pasdani and Rahelian, which are the official languages. While, Pasdani is the lingua gaullica of government and business, Rahelian is also widely used and the two are used interchangeably by Zorasan’s citizens. According to some estimates, there are over 40 different languages or dialects spoken in Zorasan. Though there is no officially recognised languages besides Pasdani and Rahelian, some of Zorasan’s states provide limited recognition or protections for minority languages.

Both Pasdani and Rahelian are taught in schools throughout a child’s school career. It is a noted national policy for lessons to be taught interchangeably between both languages to assist in educating Zorasani children into being bi-lingual. Tests in the respective opposition language are mandatory and many universities rank bi-lingual abilities as critical for a successful application. All civil service positions at the local, state and national level require fluency, as do many employers in the private sector, owing to government policies.

It is estimated that 91% of Zorasanis are bi-lingual, with 51.3% of the population speaking Pasdani as their first language and 48.7% speaking Rahelian as their first language. The bi-lingualism of Zorasan is aided by the nature of Irfan, which utilises phrases and terms in both languages, the rituals and processions of the faith also take place in both languages.

Minority languages present in Zorasan include Syriazi, which is provided some protections in the Union Republic of Irvadistan, Lashkari, which is spoken primarily in western Pardaran, along the border regions of Ajahadya and is provided some limited protection. Lashkari is the third most widely spoken language in Zorasan. The Chanwan is the fourth most widely spoken language in Zorasan but faces active repression by the Zorasani state. The use of Chanwan is prohibited in official capacities and is actively discouraged in public.

Some areas of eastern Zorasan have communities speaking Ndjarendie, a language brought over from neighbouring Mabifia, through the Bahio-Rahelian minority. The use of Ndjarendie is not opposed but lacks any formal recognition by the eastern Union Republics.

Religion

The Zorasani constitution officially designates Irfan as the state religion. Notably, the designation does not differentiate between the various sects and denominations of Irfan, providing equal rights and protections, though subsequent constitutional clauses, elevates the majority Asha denomination as the “predominate sect of the Union.” The constitution also provides recognition and protections for Sotiranity, Atudism, Yazidism and Druze.

As the birthplace of Irfan, Zorasan is home to several of the faith’s most important holy cities, including Ardakan, Namrin, Borazjan and Beyarjomand. Ardakan, Namrin and Beyarjomand are the sites of prominent religious events, with the former two taking prominent positions during the Ziyarat or “Pilgrimage.” Ardakan sees over 30 million visitors per year during Ziyarat to mark the Journey of Absolution, while Namrin is visited by 20-25 million visitors per year to mark the Martyrdom of Imam Ardashir and the 300.

Approximately 91% of Zorasan identify as Irfani, while 95% of the Irfani population are practicing members of the Asha denomination, which plays a significant role in Zorasani society and politics. The remaining 5% of Irfani in Zorasan are divided by the X and X sects, who enjoy equal rights and protections as the Asha majority.

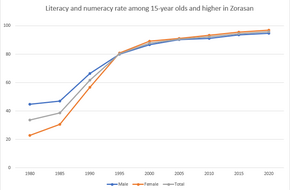

The next largest faith in Zorasan is Badi, which is practiced by 4-5% of the population, though it is actively repressed and unrecognised by the Zorasani government, owing to the historic and traditional view of the religion by Irfan as heretical and witchcraft. From 1950 until the early 1970s, the Badi population was subject to violent repression during the Estekham, in which an estimated 150,000 Badi were killed and millions more were forced to convert to Irfan. Thousands of Badi places of worship were destroyed or converted to serve Irfan and a prohibition on Badi being publicly practiced is still in place. The vast majority of Badi in Zorasan are from the Kexri majority.