Federal Congress (Morrawia)

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Federal Congress of Morrawia Morawský federální kongres | |

|---|---|

| 48th Federal Congress | |

Official seal of the Federal Congress of Morrawia | |

Official logo of the Federal Congress of Morrawia | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses | Senate of the Republic House of Representative |

| History | |

| Founded | March 1, 1836 |

| Preceded by | National Assembly |

New session started | March 8, 2024 |

| Leadership | |

President of the Senate | |

President pro tempore | |

Senate Majority Leader | |

Speaker of the House | |

House Majority Leader | |

| Structure | |

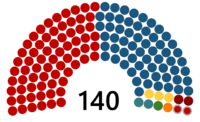

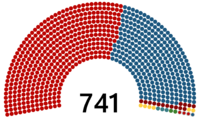

| Seats | 140 (Senate of the Republic) 741 (House of Representatives) |

| |

Political groups | Majority (71)

Minority (69)

|

| |

Political groups | Majority (428)

Minority (313)

|

| Committees |

|

| Committees |

|

Joint committees |

|

Length of term | 4 years (House) and 6 years (Senate) |

| Authority | Legislative |

| Salary | ₮457,440 (ACU 114,360) |

| Elections | |

| Single Transferable Vote (Senate) | |

| Instant-runoff (House) | |

First election | March 3rd, 1836 (founding) |

First election | March 3rd, 1842 (all congressional seats filled) |

Last election | March 7th, 2024 (Senate) |

Last election | March 7th, 2024 (House) |

Next election | March 9th, 2026 (Senate) |

Next election | March 9th, 2028 (House) |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Capitol Building Republic of Morrawia | |

| Website | |

| federalcongress | |

| Constitution | |

| Morrawian Constitution, article II | |

The Federal Congress, or simply Congress, and officially Federal Congress of the Republic of Morrawia, is the legislature of the federal government of the Republic of Morrawia. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the Morrawian House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Morrawian Senate of the Republic. It meets in the Capitol Building in Králowec, F.D. Morrawian Senators and Morrawian Representatives are chosen through direct election, though vacancies in the Senate may be filled by a governor's appointment. Federal Congress has 881 voting members: 140 senators and 741 representatives. The Morrawian vice president, as President of the Senate, has a vote in the Senate only when casting a tie-breaking vote. The House of Representatives has one non-voting member.

Federal Congress convenes for a four-year term, commencing in March. Elections are held every even-numbered year on Election Days. The members of the House of Representatives are elected for the four-year term of a Federal. The Reapportionment Act of 1995 established that there be 741 representatives, and the Uniform Congressional Redistricting Act requires that they be elected from single-member constituencies or districts. It is also required that the congressional districts be apportioned among states by population every ten years using the Morrawian census results, provided that each state has at least one congressional representative. Each senator is elected at-large in their state for a six-year term, with terms staggered, so every two years approximately one-third of the Senate is up for election. Each state, regardless of population or size, has seven senators, so currently, there are 140 senators for the 20 states.

Article Two of the Morrawian Constitution requires that members of the Federal Congress must be at least 18 years old for the House and at least 30 years old for the Senate of the Republic, be a citizen of the Morrawia for five years for the House and nine years for the Senate, and be an inhabitant of the state which they represent. Members in both chambers may stand for re-election an unlimited number of times, though they are limited by the national retirement age as per relevant legislation.

The Federal Congress was created by the Morrawian Constitution and first met in 1836, replacing the National Assembly in its legislative function. Although not legally mandated, in practice since the 19th century, Federal Congress members are typically affiliated with one of the two major parties, in contemporary period, that is the Liberal Party or the Republican Party, and and in fewer cases with third or other party or independents affiliated with no party. In the case of the latter, the lack of affiliation with a political party does not mean that such members are unable to caucus with members of the political parties. Members can also switch parties at any time, although this is quite uncommon.

Overview

History

Women in the Federal Congress

Role

Structure

Procedures

Sessions

A term of the Federal Congress is divided into four "sessions", one for each year. The Federal Congress has occasionally been called into an extra or special session. A new session commences on March 8 each year unless the Federal Congress decides differently. The Constitution requires the Federal Congress to meet at least once each year and forbids either house from meeting outside the Capitol without the consent of the other house.

Joint sessions

Joint sessions of the Federal Congress occur on special occasions that require a concurrent resolution from House and Senate. These sessions include certifying election results after a presidential election and the president's State of the Union address. The constitutionally mandated report, normally given as an annual speech, is modeled on previous Emperor´s Declaration, was written by most presidents after Soukup but personally delivered as a spoken oration beginning with Wáclaw Morawċík in 1906. Joint Sessions and Joint Meetings are traditionally presided over by the speaker of the House, except when counting presidential electoral results when the vice president (acting as the president of the Senate) presides.

Bills and resolutions

Ideas for legislation can come from members, lobbyists, state legislatures, constituents, legislative counsel, or executive agencies. Anyone can write a bill, but only members of Congress may introduce bills. Most bills are not written by Federal Congress members, but originate from the Executive branch. Interest groups often draft bills as well. The usual next step is for the proposal to be passed to a committee for review an advisory purposes. A proposal is usually in one of these forms:

Bills - Laws in the making. A House-originated bill begins with the letters "D.K." for "Dolní komora" or "lower chamber", followed by a number kept as it progresses.

Joint resolutions - There is little difference between a bill and a joint resolution since both are treated similarly. A joint resolution originating from the House, for example, begins "U.D.K." followed by its number.

Concurrent resolutions - They affect only the House and Senate and accordingly are not presented to the president. In the House, they begin with "S.U.D.K."

Simple resolutions - These concern only the House or only the Senate and begin with "J.U.D.K." or "J.U.H.K."

Representatives introduce a bill while the House is in session by placing it in the hopper on the Clerk's desk. It is assigned a number and referred to a committee which studies each bill intensely at this stage. Drafting statutes requires "great skill, knowledge, and experience" and sometimes take a year or more. Sometimes lobbyists write legislation and submit it to a member for introduction. Joint resolutions are the normal way to propose a constitutional amendment or declare war. On the other hand, concurrent resolutions (passed by both houses) and simple resolutions (passed by only one house) do not have the force of law but express the opinion of the Federal Congress or regulate procedure. Bills may be introduced by any member of either house. The Constitution states: "All bills for raising revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives". While the Senate cannot originate revenue and appropriation bills, it has the power to amend or reject them. Federal Congress has sought ways to establish appropriate spending levels.

Each chamber determines its own internal rules of operation unless specified in the Constitution or prescribed by law. In the House, a Rules & Administration Committee guides legislation; in the Senate, a Oversight, Accountability & Administration committee is in charge. Each branch has its own traditions. For example, the Senate relies heavily on the practice of getting "unanimous consent" for noncontroversial matters. House and Senate rules can be complex, sometimes requiring a hundred specific steps before a bill can become a law. Members sometimes turn to outside experts to learn about proper congressional procedures.

Each bill goes through several stages in each house including consideration by a committee and advice from the Supreme Audit Bureau. Most legislation is considered by standing committees which have jurisdiction over a particular subject such as Agriculture or Appropriations. The House has fifteen standing committees; the Senate has twenty-one. Standing committees meet at least once each month. Almost all standing committee meetings for transacting business must be open to the public unless the committee votes, publicly, to close the meeting. A committee might call for public hearings on important bills. Each committee is led by a chair who belongs to the majority party and a ranking member of the minority party. Witnesses and experts can present their case for or against a bill. Then, a bill may go to what is called a mark-up session, where committee members debate the bill's merits and may offer amendments or revisions. Committees may also amend the bill, but the full house holds the power to accept or reject committee amendments. After debate, the committee votes whether it wishes to report the measure to the full house. If amendments are extensive, sometimes a new bill with amendments built in will be submitted as a so-called clean bill with a new number. Both houses have procedures under which committees can be bypassed or overruled but they are rarely used. Generally, members who have been in the Federal Congress longer have greater seniority and therefore greater power.

A bill which reaches the floor of the full house can be simple or complex and begins with an enacting formula such as "Be it enacted by the Senate of the Republic and House of Representatives of the Republic of Morrawia in the Federal Congress assembled ..." Consideration of a bill requires, itself, a rule which is a simple resolution specifying the particulars of debate – time limits, possibility of further amendments, and such. Each side has equal time and members can yield to other members who wish to speak. Sometimes opponents seek to recommit a bill which means to change part of it. This is all happening in the three readings system in which the whole process operates. One additional reading to the so-called pre-reading time is then utilized in the second chamber. The house may debate and amend the bill. Generally, discussion requires a quorum, usually half of the total number of representatives, before discussion can begin, although there are exceptions. The precise procedures used by the House and Senate differ. A final vote on the bill follows.

Once a bill is approved by one house, it is sent to the other which may pass, reject, or amend it. For the bill to become law, both houses must agree to identical versions of the bill. If the second house amends the bill, then the differences between the two versions must be reconciled in a conference committee, an ad hoc committee that includes senators and representatives sometimes by using a reconciliation process to limit budget bills. Both houses use a budget enforcement mechanism informally known as pay-as-you-go or paygo which discourages members from considering acts that increase budget deficits. If both houses agree to the version reported by the conference committee, the bill passes, otherwise it fails.

The Constitution specifies that a majority of members (a quorum) be present before doing business in each house. The rules of each house assume that a quorum is present unless a quorum call demonstrates the contrary and debate often continues despite the lack of a majority.

Voting within the Federal Congress can take many forms, including systems using lights and bells and electronic voting. Both houses use voice voting to decide most matters in which members shout "aye" or "no" and the presiding officer announces the result. The Constitution requires a recorded vote if demanded by one-fifth of the members present or when voting to override a presidential veto. If the voice vote is unclear or if the matter is controversial, a recorded vote usually happens. The Senate uses roll-call voting, in which a clerk calls out the names of all the senators, each senator stating "aye" or "no" when their name is announced. In the Senate, the Vice President may cast the tie-breaking vote if present when the senators are equally divided.

The House reserves roll-call votes for the most formal matters, as a roll call of all 741 representatives takes quite some time. Normally, members vote by using an electronic device. In the case of a tie, the motion in question fails. Most votes in the House are done electronically, allowing members to vote yea or nay or present or open. Members insert a voting ID card and can change their votes during the last five minutes if they choose. In addition, paper ballots are used occasionally (yea indicated by green and nay by red). One member cannot cast a proxy vote for another. Congressional votes are recorded on an online database.

After passage by both houses, a bill is enrolled and sent to the president for approval. The president may sign it making it law or veto it, perhaps returning it to the Federal Congress with the president's objections. A vetoed bill can still become law if each house of Congress votes to override the veto with a two-thirds majority. Finally, the president may do nothing neither signing nor vetoing the bill and then the bill becomes law automatically after ten days (not counting Sundays) according to the Constitution. But if Congress is adjourned during this period, presidents may veto legislation passed at the end of a congressional session simply by ignoring it. The maneuver is known as a pocket veto, and cannot be overridden by the adjourned Federal Congress.

Public interaction

Advantage of incumbency

Citizens and representatives

Senators face reelection every six years, and representatives every four. Reelections encourage candidates to focus their publicity efforts at their home states or districts. Running for reelection can be a grueling process of distant travel and fund-raising which distracts senators and representatives from paying attention to governing, according to some critics. Although others respond that the process is necessary to keep members of the Federal Congress in touch with voters.

Incumbent members of the Federal Congress running for reelection have strong advantages over challengers. They raise more money because donors fund incumbents over challengers, perceiving the former as more likely to win, and donations are vital for winning elections. One critic compared election to the Federal Congress to receiving life tenure at a university. Another advantage for representatives is the practice of redistricting, though in recent years, several legislation severely restricted the practice. After each ten-year census, states are allocated representatives based on population, and officials in power can choose how to draw the congressional district boundaries to support candidates from their party with several limitations and guidelines. As a result, reelection rates of members of Congress hover around 90 percent, causing some critics to call them a privileged class. Academics such as National University of Králowec's Ṡtėpán Makád have proposed solutions to fix redistricting in Morrawia for good with mandatory non-partisan groups in every state as a part of Federal Election Commission. Senators and representatives enjoy free mailing privileges, called franking privileges. While these are not intended for electioneering, this rule is often skirted by borderline election-related mailings during campaigns.

Expensive campaigns

In 1971, the cost of running for Congress in Dalmate was ₮20,000 but costs have climbed. The biggest expense is television advertisements. Today's races cost more than a hundred thousand tollars for a House seat, and two hundred thousand or more for a Senate seat. Since fundraising is vital, "members of Congress are forced to spend ever-increasing hours raising money for their re-election".

In the 1970s the Constitutional Tribunal has been asked to determine whether the regulatory finance laws violated donors free speech. Some saw money as a good influence in politics since it "enables candidates to communicate with voters". In the split decision Free Morrawia v. FEC the court held 5–4 that the freedom of speech is not violated by the government when restricting independent expenditures for political campaigns by corporations, nonprofit organizations, labor unions, and other associations, thus supporting the New Campaign Reform Act of 1972. This is by many seen as one of the most consequential rulings in Morrawian history, which at least to certain extent kept large amounts of money out of politics, thus strengthening Morrawian democracy.

Elections are influenced by many variables. Some political scientists speculate there is a coattail effect (when a popular president or party position has the effect of reelecting incumbents who win by "riding on the president's coattails"), although there is some evidence that the coattail effect is irregular and possibly declining since the 1960s. Some districts are so heavily Liberal or Republican or other that they are called a safe seat. Any candidate winning the primary will almost always be elected, and these candidates do not need to spend money on advertising. But some races can be competitive when there is no incumbent. If a seat becomes vacant in an open district, then both parties may spend heavily on advertising in these races. In Pomaria in 1992, only four of twenty races for House seats were considered highly competitive.

Television and negative advertising

Since members of the Federal Congress must advertise heavily on television, this usually involves negative advertising, which smears an opponent's character without focusing on the issues. Negative advertising is seen as effective because "the messages tend to stick". These advertisements sour the public on the political process in general as most members of the Federal Congress seek to avoid blame. One wrong decision or one damaging television image can mean defeat at the next election, which leads to a culture of risk avoidance, a need to make policy decisions behind closed doors, and concentrating publicity efforts in the members' home districts.

Since at least 1960s, there has been mixed efforts to quell the effects of negative advertising with the majority of these attempts ending with the reading period in one of the chambers, due to fears of the freedom of speech violations. Some minor acts like the Campaign Management Act of 1985 were meant for limiting the disinformation wave against the opposing candidate, which has become increasingly popular in the decades prior. Most recent attempt was in 2020 with the ECO (Election Campaign Organization) Act was struck down by the Constitutional Tribunal for its vage and broad terms regarding mainly it´s provisions about personal attacks on non-campaigning individuals.

Perceptions

Prominent Founding Fathers, felt that elections were essential to liberty, that a bond between the people and the representatives was particularly essential, and that "frequent enough elections are unquestionably the only policy by which this dependence and sympathy can be effectually secured". In 2010, few Morrawians were familiar with leaders of the Federal Congress. The percentage of Morrawians eligible to vote who did, in fact, vote was 68% in 1960, but has been falling since, although there was a slight upward trend in the 2016 election. Public opinion polls asking people if they approve of the job the Federal Congress is doing have, in the last few decades, hovered around 31% with some variation. Scholar Julián Zelger suggested that the "size, messiness, virtues, and vices that make the Federal Congress so interesting also create enormous barriers to our understanding the institution ... Unlike the presidency, Federal Congress is difficult to conceptualize". Other scholars suggest that despite the criticism, "Federal Congress is a remarkably resilient institution ... its place in the political process is not threatened ... it is rich in resources" and that most members behave ethically. They contend that "Congress is easy to dislike and often difficult to defend" and this perception is exacerbated because many challengers running for Congress run against Congress, which is an "old form of Morrawian politics" that further undermines Federal Congress's reputation with the public.

An additional factor that confounds public perceptions of the Federal Congress is that congressional issues are becoming more technical and complex and require expertise in subjects such as science, engineering and economics. As a result, Congress often cedes authority to experts at the executive branch.

Since 2001, Congress has dropped ten points in the formal confidence poll with only twelve percent having "a great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in their legislators. Since 2011, the poll has reported Congress's approval rating among Morrawians at 16% or below three times. Public opinion of the Federal Congress plummeted further to 9% in October 2007 after parts of the Morrawians government deemed "nonessential government" were gutted and some even shut down as a part of austerity measures.

Smaller states and bigger states

When the Constitution was ratified in 1836, the ratio of the populations of large states to small states was roughly ten to one. The Sollandy Compromise gave every state, large and small, an equal vote in the Senate. Since each state has two senators, residents of smaller states have more clout in the Senate than residents of larger states. But since 1836, the population disparity between large and small states has grown. In 2010, for example, Elbennau had twenty times the population of Tawuii. Critics, such as constitutional scholar Florian Weinberg, have suggested that the population disparity works against residents of large states and causes a steady redistribution of resources from "large states to small states". Others argue that the Sollandy Compromise was deliberately intended by the Founding Fathers to construct the Senate so that each state had equal footing not based on population, and contend that the result works well on balance.

Members and constituents

A major role for members of the Federal Congress is providing services to constituents. Constituents request assistance with problems. Providing services helps members of the Federal Congress win votes and elections and can make a difference in close races. Congressional staff can help citizens navigate government bureaucracies. One academic described the complex intertwined relation between lawmakers and constituents as home style.

Motivation

One way to categorize lawmakers, according to former University of Tatrany political science professor Richard Fenský, is by their general motivation:

- Reelection: These are lawmakers who "never met a voter they didn't like" and provide excellent constituent services.

- Good public policy: Legislators who "burnish a reputation for policy expertise and leadership".

- Power in the chamber: Lawmakers who spend serious time along the "rail of the House floor or in the Senate cloakroom ministering to the needs of their colleagues". Famous legislator Honoré Mallate in the mid-19th century was described as an "issue entrepreneur" who looked for issues to serve his ambitions.

Privileges

Pay

Some critics complain congressional pay is high compared with a median Morrawian income. Others have countered that congressional pay is consistent with other branches of government. Another criticism is that members of the Federal Congress are insulated from the health care market due to their much better coverage. Others have criticized the wealth of members of the Federal Congress. In January 2014, it was reported that for the first time over one third of the members of the Congress were millionaires. Federal Congress has been criticized for trying to conceal pay raises by slipping them into a large bill at the last minute.

Members elected since 1979 are covered by the Federal Employees Retirement System (FERS). Like other federal employees, congressional retirement is funded through taxes and participants' contributions. Members of Congress under FERS contribute 2.5% of their salary into the FERS retirement plan and pay 5.2% of their salary in Social Security taxes. And like federal employees, members contribute one-third of the cost of health insurance with the government covering the other two-thirds. The size of a congressional pension depends on the years of service and the average of the highest three years of their salary. By law, the starting amount of a member's retirement annuity may not exceed 80% of their final salary. In 2018, the average annual pension for retired senators and representatives under the Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS) was ₮154,491, while those who retired under FERS, or in combination with CSRS, was ₮95,480.

Members of Congress make fact-finding missions to learn about other countries and stay informed, but these outings can cause controversy if the trip is deemed excessive or unconnected with the task of governing. For example, The Imperial Street Journal reported in 2015 that lawmaker trips abroad at taxpayer expense had included spas, ₮1 800-per-night extra unused rooms, and shopping excursions. Some lawmakers responded that "traveling with spouses compensates for being away from them a lot in Králowec" and justify the trips as a way to meet officials in other nations.

Postage

The franking privilege allows members of the Federal Congress to send official mail to constituents at government expense. Though they are not permitted to send election materials, borderline material is often sent, especially in the run-up to an election by those in close races. Some academics consider free mailings as giving incumbents a big advantage over challengers.

Protection

Members of Congress enjoy parliamentary privilege, including freedom from arrest in all cases except for treason, felony, and breach of the peace, and freedom of speech in debate. This constitutionally derived immunity applies to members during sessions and when traveling to and from sessions. The term "arrest" has been interpreted broadly, and includes any detention or delay in the course of law enforcement, including court summons and subpoenas. The rules of the House strictly guard this privilege. A member may not waive the privilege on their own but must seek the permission of the whole house to do so. Senate rules are less strict and permit individual senators to waive the privilege as they choose.

The Constitution guarantees absolute freedom of debate in both houses, providing in the Constitution that "for any speech or debate in either House, they shall not be questioned in any other Place". Accordingly, a member of the Federal Congress may not be sued in court for slander because of remarks made in either house, although each house has its own rules restricting offensive speeches, and may punish members who transgress.

Obstructing the work of the Federal Congress is a crime under federal law and is known as contempt of the Federal Congress. Each member has the power to cite people for contempt but can only issue a contempt citation – the judicial system pursues the matter like a normal criminal case. If convicted in court of contempt of the Federal Congress, a person may be imprisoned for up to one year.