Riamese intervention in Anáhuac: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (17 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{wip}} | {{wip}} | ||

{{Infobox military conflict | {{Infobox military conflict | ||

| conflict = Riamese intervention in | | conflict = Riamese intervention in Anáhuac | ||

| width = 350px | | width = 350px | ||

| image = File:Mexican War Montage.jpg | | image = File:Mexican War Montage.jpg | ||

| image_size = 300px | | image_size = 300px | ||

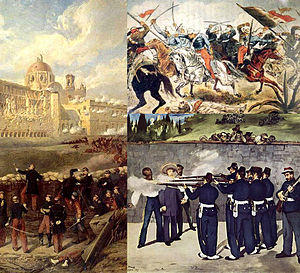

| caption = Clockwise from left: Riamese assault during the [[Siege of Santiago de Lujambio (1863)|Second Battle of Santiago de Lujambio]]; [[Riamese Armed Forces|Riamese cavalry]] seize the Republican flag during the [[Battle of | | caption = Clockwise from left: Riamese assault during the [[Siege of Santiago de Lujambio (1863)|Second Battle of Santiago de Lujambio]]; [[Riamese Armed Forces|Riamese cavalry]] seize the Republican flag during the [[Battle of Chalma]]; Execution of monarchist generals. | ||

| date = 8 December 1861 - 21 June 1869 | | date = 8 December 1861 - 21 June 1869 | ||

| place = [[ | | place = [[Anáhuac]] | ||

| result = Monarchist victory during the majority of the war: | | result = Monarchist victory during the majority of the war: | ||

* Proclamation of the | * Proclamation of the Kingdom of Anahuac | ||

Republican victory in the final year: | Republican victory in the final year: | ||

* Fall of the | * Fall of the Kingdom of Anahuac | ||

* Riamese withdrawal from | * Riamese withdrawal from Anahuac, except from [[Riamese occupation of Isla Roca Roja|Isla Roca Roja]] | ||

| combatant1 = {{flagicon| | | combatant1 = {{flagicon|Anáhuac|Federal}} Republic of Anahuac | ||

| combatant2 = {{flagicon| | | combatant2 = {{flagicon|Anáhuac|Second Empire}} [[Kingdom of Anahuac]] <br> {{flagicon|Riamo|empire}} [[Riamese Empire]] </br> | ||

| combatant3 = | | combatant3 = | ||

| commander1 = {{flagicon| | | commander1 = {{plainlist| | ||

| commander2 = {{flagicon| | * {{flagicon|Anáhuac|Federal}} [[Enciclopedia General del Anáhuac#Reform War & Kingdom of Anáhuac (1856 - 1869)|Raymundo Vigil]] | ||

| strength1 = {{flagicon| | * {{flagicon|Anáhuac|Federal}} [[Enciclopedia General del Anáhuac#Lenociato Era (1875 - 1910)|Ángel Lenoci]] | ||

| strength2 = | * {{flagicon|Anáhuac|Federal}} [[Enciclopedia General del Anáhuac#Lenociato Era (1875 - 1910)|Ramiro Gonzlaéz Flores]] | ||

* {{flagicon|Anáhuac|Federal}} [[Enciclopedia General del Anáhuac#Reform War & Kingdom of Anáhuac (1856 - 1869)| Nicolás Mendoza]] {{KIA}} | |||

* {{flagicon|Anáhuac|Second Empire}} [[Enciclopedia General del Anáhuac#Reform War & Kingdom of Anáhuac (1856 - 1869)|Tulio I]] | |||

}} | |||

| commander2 = {{plainlist| | |||

* {{flagicon|Riamo|empire}} [[Who's Who#Kate Watergate|Kate Watergate]] | |||

* {{flagicon|Riamo|empire}} [[Who's Who#Frank Sweetenham|Frank Sweetenham]] | |||

* {{flagicon|Anáhuac|Second Empire}} [[Enciclopedia General del Anáhuac#Reform War & Kingdom of Anáhuac (1856 - 1869)|Cristobal I]]{{Executed}} | |||

* {{flagicon|Anáhuac|Second Empire}} [[Enciclopedia General del Anáhuac#Reform War & Kingdom of Anáhuac (1856 - 1869)|Martín Sánchez Chagollán]] {{KIA}} | |||

* {{flagicon|Anáhuac|Second Empire}} [[Enciclopedia General del Anáhuac#Reform War & Kingdom of Anáhuac (1856 - 1869)|Gregorio Atenógenes]] | |||

}} | |||

| strength1 = {{flagicon|Anáhuac|Federal}} 70,000 | |||

| strength2 = {{flagicon|Riamo|empire}} 38,493 | |||

| strength3 = | | strength3 = | ||

| casualties1 = 31,962 killed <br> 8,304 wounded <br> 33,281 captured <br> 11,000 executed | | casualties1 = 31,962 killed <br> 8,304 wounded <br> 33,281 captured <br> 11,000 executed | ||

| Line 28: | Line 40: | ||

}} | }} | ||

The '''Riamese intervention in Anáhuac''' (Spanish: ''Intervención riamesa en Anáhuac'') also known as the '''Riamese-Anahuense War''' (1861–1869) <ref>Also known as ''Expedition to Anáhuac'' in Riamo at the time</ref> was an invasion of the [[Anáhuac|Republic of Anáhuac]], launched in late 1862 by the [[Riamese Empire]]. It helped {{wp|Regime change|replace}} the republic with a monarchy, known as the [[Anáhuac|Kingdom of Anahuac]], ruled by ''hueyitlahtoani'' [[Enciclopedia General del Anáhuac#Reform War & Empire of Chalco (1856 - 1867)|Cristóbal I]]. | |||

During the civil war known as the [[Reform War]], the Republican adminstration of [[Enciclopedia General del Anáhuac#Reform War & Empire of Chalco (1856 - 1867)|Raymundo Vigil]] placed a moratorium on foreign debt payments in 1859. Of the powers involved, Riamo was the only one who unilaterally planned to seize Anahuac as a {{wp|Show of force|show of force}} to ensure that debt repayments would be forthcoming. On 8 December 1861, the Riamese Navy blocked important port cities of the [[Sunadic Ocean|Sunadic]] and the [[Kaldaz Ocean|Kaldaz]], such as [[Santiago de Lujambio]] and [[Santa Elisa]]. The subsequent invasion of San Jorge Xayacatlán established the [[Kingdom of Anahuac]]. | |||

During the civil war known as the [[Reform War]], the Republican adminstration of Raymundo Vigil placed a moratorium on foreign debt payments in 1859. Of the powers involved, Riamo was the only one who unilaterally planned to seize | |||

The intervention came as the Reform War, had just concluded, and the intervention allowed the Conservative opposition against the liberal social and economic reforms of President Vigil to take up their cause once again. The | The intervention came as the Reform War, had just concluded, and the intervention allowed the Conservative opposition against the liberal social and economic reforms of President Vigil to take up their cause once again. The Anahuacian Catholic Church, Anahuac conservatives, much of the upper-class and nobility, and some Native Anahuacian communities invited, welcomed and collaborated with the Riamese empire's help to legitimize the cause of Cristóbal I. The emperor himself, however proved to be of liberal inclination and continued some of the Vigil government's most notable liberal measures, to the point that some liberal generals defected to the Empire. | ||

The Riamese and | The Riamese and Anahuense Imperial Army rapidly captured much of Republican territory, including major cities, but guerrilla warfare remained rampant, and the intervention was increasingly using up troops and money at a time, forcing Riamo to enter negotiations with Republican forces. Riamo would eventually left the country in 1869, but keeping the territory of [[Riamese occupation of Isla Roca Roja|Isla Roca Roja]] as reparation of the national debt. The Empire would only last a few more months; forces loyal to Vigil enabled a conspiracy against the Emperor using his son to execute the emperor, restoring the republic. | ||

== Background == | == Background == | ||

While a minor trade partner at the time, the [[ | While a minor trade partner at the time, the [[Riamese Empire]] was still one of the major creditors in Anahuac. The intervention was a consequence of Anahuacian President Raymundo Vigil's imposition of a two-year moratorium of loan-interest payments from July 1859 to foreign creditors. The [[Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores|Minister of Foreign Relations]] at the time, [[Enciclopedia General del Anáhuac#Reform War & Empire of Chalco (1856 - 1867)|Vicente LaFourcade]] was sent by Vigil to negotiate with each major creditor to persuade all that the suspension of debts was temporary. The Riamese delegates however, saw Vigil's debt moratorium as a pretext for intervention and a {{wp|Show of force|show of force}} of Olivacian powers. | ||

== History == | == History == | ||

| Line 45: | Line 56: | ||

=== The Long March === | === The Long March === | ||

On 2 January 1861, a Riamese fleet sailed into and took possession of the port of Santiago de Lujambio. The city was occupied on the 17. The remaining forces arrived on 13 | On 2 January 1861, a Riamese fleet sailed into and took possession of the port cities of Santiago de Lujambio and the capital of [[San Jorge Xayacatlán]]. The city of Santiago was occupied on the 17. The remaining forces arrived on 13 March 1861, blocking other ports in the [[Sunadic Ocean|Sunadic]] and the [[Kaldaz Ocean|Kaldaz]]. On 10 June, a manifesto was issued by Riamese generals disavowing rumors that the allies had come to conquer or to impose a new government. It was emphasized that the Nostrian empire merely wanted to open negotiations regarding their claims of damages. | ||

LaFourcade was quickly called back to Anahuac. The minister initiated an exchange of notes with the claimant government. Given the urgency of the situation, the [[Congress of the Union|National Congress]] empowered the government to take all appropriate measures in order to save independence, defend the integrity of the territory, as well as the form of government prescribed in the Constitution and the Reform Laws. | |||

=== Riamese invasion === | |||

On 8 December 1861, negotiations between the Riamese and the government of Vigil broke down when Riamese soldiers fired shots at Anahuacian soldiers on the Santiago port. During the previous weeks, Riamese authorities had slowly made it increasingly obvious that the true nature of the intervention was not solely to demonstrate force, but that the total conquest of Anahuac had never been discarded, and while no official statements had made it official, it was obvious that the real intention was to interfere with the Anahuacian government in violation of previous treaties. Despite this, i it is to be noted certain Anahuacan officers had been sympathetic to the Riamese since the beginning of the intervention. | |||

On 16 December 1862, the Riamese issued a proclamation inviting Anahuacians to join them in establishing a new government. The next day, however, Rugidoense general [[Enciclopedia General del Anáhuac#Reform War & Empire of Chalco (1856 - 1867)|Clemente Saenz]], who had been a foreign minister of the conservative government during the [[Reform War]] and who had been brought back to Anahuac by the Riamese, released his own statement the following day, in which he assured the Anahuense people of benevolent Riamese intentions. A key figure in the pacification of the Anahuacan people was [[Who's Who#Frank_Sweetenham|Frank Sweetenham]], a Riamese diplomat of Anahuacan descent who had come to understand locals and served as a key inside person to assure Anahuacan interests would allign with Riamese once the intervention had ended. | |||

On February 1863, reinforcements consisting of 30,000 men were sent out from Riamo who were also given a set of instructions for laying out Riamo's occupation policy. The instructions directed Riamese generals to work with Anahuacian supporters in the pursuit of both military and political goals. The main objective of the contingent remained on leading Anahuacians to create their own new government, under the Riamese blanket, but not by the Riamese, following the same philosophy the empire had been using to conquest territories across Anteria. Following this, a new government was to be set up, friendly to Riamese interests. Seeing the support of the imperials, a number of officials and oligarchic figures saw it as an opportunity to make a change for the better under Riamese tutelage, result of which was the proclamation of the [[Kingdom of Anahuac]]. | |||

The ''Grito de Ferraz'' (Common: Cry of Ferraz) was the first of a series of army revolts in favor of the Riamese. It was a small scale mutinee of army general XXX XXX on XXX's garrison. Ferraz, a low-ranking officer at the time, convinced a large portion of his line to insurrect against their ultra-catholic and conservative officials, and, during the night of December 12th, took over the garrison. The operation, which started silently by the sunset, would become a backyard bloodbath by midnight, with linemen against linemen shooting across all levels of the garrison, with at least 7 counts of side-switching mid-conflict being accounted for. | |||

At the end, the garrison was taken by the insurgents, and while they would later surrender two days later, their stories would inspire another 4 mutinees in or nearby the cities held by Riamese soldiers. Most notable is the case of ''Fuerte Ovejuna'' (often translated as "Sheepesse Fort"), whose mutinees joined the Riamese effort after making an improvised Riamese flag with blood and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cypripedium_irapeanum Pelican Orchid] squeeze, for which the insurgency was deemed the "Orchid Uprising". | |||

=== Establishment of the Kingdom === | |||

''Main articles: [[Kingdom of Anahuac]], [[Enciclopedia General del Anáhuac|Cristobál de Anahuac]]'' | |||

[[File:Entrée du corps expéditionnaire français à Mexico, juin 1863.jpg|150px|thumb|right|Riamese troops enter San Jorge Xayacatlán]] | |||

During the siege of San Jorge Xayacatlán, President Vigil prepared to evacuate the capital and move the republican government to Zaragoza de Seguín. Congress closed its session on 31 May after granting Vigil emergency powers. The Riamese captured the capital on 10 June 1863. | |||

On 16 June the Riamese government's instructions of occupation were set on motion. Under Riamese tutelage, 35 Anahuense citizens were nominated to constitute a Junta Superior de Gobierno who were then tasked with electing a triumvirate that was to serve as the executive of the new government. The three elected were Fulgencio Belarmino, Edelmiro Luján and Pedro Nierman. Occupation forces also to choose 215 Anahuense citizens who together with the Junta Superior were to constitute an Assembly of Notables that was to decide upon the form of government. On 11 July, the Assembly was deposed by conservative group ''Acción Nacional'' (Common: National Action) who then imposed their leader as monarch. He took the name Cristobál de Anáhuac and ascended to the newly formed Anahuense throne. While instability was feared by the Riamese, the executive was officially changed into the Regency of the Kingdom of Anahuac with no issues. | |||

Although Republican guerrilla forces in the countryside around the capital counted no victories against the Riamese, they maintained a presence. Tizayuca was captured by imperial forces on 29 July 1863. Republican guerrilla commanders Ángel Lenoci and Damián Escobedo, and others continued to wage warfare against towns occupied by the Riamese. | |||

=== Imperialist successes === | |||

=== | === Northern Campaign === | ||

== Decline of imperial military control == | |||

| Line 76: | Line 112: | ||

{{Template:Anteria info pages}} | {{Template:Anteria info pages}} | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Anáhuac]] | ||

[[Category:Riamo]] | |||

[[Category:Anteria]] | [[Category:Anteria]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:15, 1 January 2024

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

| Riamese intervention in Anáhuac | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Clockwise from left: Riamese assault during the Second Battle of Santiago de Lujambio; Riamese cavalry seize the Republican flag during the Battle of Chalma; Execution of monarchist generals. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

31,962 killed 8,304 wounded 33,281 captured 11,000 executed | 14,000 killed | ||||||

The Riamese intervention in Anáhuac (Spanish: Intervención riamesa en Anáhuac) also known as the Riamese-Anahuense War (1861–1869) [1] was an invasion of the Republic of Anáhuac, launched in late 1862 by the Riamese Empire. It helped replace the republic with a monarchy, known as the Kingdom of Anahuac, ruled by hueyitlahtoani Cristóbal I.

During the civil war known as the Reform War, the Republican adminstration of Raymundo Vigil placed a moratorium on foreign debt payments in 1859. Of the powers involved, Riamo was the only one who unilaterally planned to seize Anahuac as a show of force to ensure that debt repayments would be forthcoming. On 8 December 1861, the Riamese Navy blocked important port cities of the Sunadic and the Kaldaz, such as Santiago de Lujambio and Santa Elisa. The subsequent invasion of San Jorge Xayacatlán established the Kingdom of Anahuac.

The intervention came as the Reform War, had just concluded, and the intervention allowed the Conservative opposition against the liberal social and economic reforms of President Vigil to take up their cause once again. The Anahuacian Catholic Church, Anahuac conservatives, much of the upper-class and nobility, and some Native Anahuacian communities invited, welcomed and collaborated with the Riamese empire's help to legitimize the cause of Cristóbal I. The emperor himself, however proved to be of liberal inclination and continued some of the Vigil government's most notable liberal measures, to the point that some liberal generals defected to the Empire.

The Riamese and Anahuense Imperial Army rapidly captured much of Republican territory, including major cities, but guerrilla warfare remained rampant, and the intervention was increasingly using up troops and money at a time, forcing Riamo to enter negotiations with Republican forces. Riamo would eventually left the country in 1869, but keeping the territory of Isla Roca Roja as reparation of the national debt. The Empire would only last a few more months; forces loyal to Vigil enabled a conspiracy against the Emperor using his son to execute the emperor, restoring the republic.

Background

While a minor trade partner at the time, the Riamese Empire was still one of the major creditors in Anahuac. The intervention was a consequence of Anahuacian President Raymundo Vigil's imposition of a two-year moratorium of loan-interest payments from July 1859 to foreign creditors. The Minister of Foreign Relations at the time, Vicente LaFourcade was sent by Vigil to negotiate with each major creditor to persuade all that the suspension of debts was temporary. The Riamese delegates however, saw Vigil's debt moratorium as a pretext for intervention and a show of force of Olivacian powers.

History

The Long March

On 2 January 1861, a Riamese fleet sailed into and took possession of the port cities of Santiago de Lujambio and the capital of San Jorge Xayacatlán. The city of Santiago was occupied on the 17. The remaining forces arrived on 13 March 1861, blocking other ports in the Sunadic and the Kaldaz. On 10 June, a manifesto was issued by Riamese generals disavowing rumors that the allies had come to conquer or to impose a new government. It was emphasized that the Nostrian empire merely wanted to open negotiations regarding their claims of damages.

LaFourcade was quickly called back to Anahuac. The minister initiated an exchange of notes with the claimant government. Given the urgency of the situation, the National Congress empowered the government to take all appropriate measures in order to save independence, defend the integrity of the territory, as well as the form of government prescribed in the Constitution and the Reform Laws.

Riamese invasion

On 8 December 1861, negotiations between the Riamese and the government of Vigil broke down when Riamese soldiers fired shots at Anahuacian soldiers on the Santiago port. During the previous weeks, Riamese authorities had slowly made it increasingly obvious that the true nature of the intervention was not solely to demonstrate force, but that the total conquest of Anahuac had never been discarded, and while no official statements had made it official, it was obvious that the real intention was to interfere with the Anahuacian government in violation of previous treaties. Despite this, i it is to be noted certain Anahuacan officers had been sympathetic to the Riamese since the beginning of the intervention.

On 16 December 1862, the Riamese issued a proclamation inviting Anahuacians to join them in establishing a new government. The next day, however, Rugidoense general Clemente Saenz, who had been a foreign minister of the conservative government during the Reform War and who had been brought back to Anahuac by the Riamese, released his own statement the following day, in which he assured the Anahuense people of benevolent Riamese intentions. A key figure in the pacification of the Anahuacan people was Frank Sweetenham, a Riamese diplomat of Anahuacan descent who had come to understand locals and served as a key inside person to assure Anahuacan interests would allign with Riamese once the intervention had ended.

On February 1863, reinforcements consisting of 30,000 men were sent out from Riamo who were also given a set of instructions for laying out Riamo's occupation policy. The instructions directed Riamese generals to work with Anahuacian supporters in the pursuit of both military and political goals. The main objective of the contingent remained on leading Anahuacians to create their own new government, under the Riamese blanket, but not by the Riamese, following the same philosophy the empire had been using to conquest territories across Anteria. Following this, a new government was to be set up, friendly to Riamese interests. Seeing the support of the imperials, a number of officials and oligarchic figures saw it as an opportunity to make a change for the better under Riamese tutelage, result of which was the proclamation of the Kingdom of Anahuac.

The Grito de Ferraz (Common: Cry of Ferraz) was the first of a series of army revolts in favor of the Riamese. It was a small scale mutinee of army general XXX XXX on XXX's garrison. Ferraz, a low-ranking officer at the time, convinced a large portion of his line to insurrect against their ultra-catholic and conservative officials, and, during the night of December 12th, took over the garrison. The operation, which started silently by the sunset, would become a backyard bloodbath by midnight, with linemen against linemen shooting across all levels of the garrison, with at least 7 counts of side-switching mid-conflict being accounted for.

At the end, the garrison was taken by the insurgents, and while they would later surrender two days later, their stories would inspire another 4 mutinees in or nearby the cities held by Riamese soldiers. Most notable is the case of Fuerte Ovejuna (often translated as "Sheepesse Fort"), whose mutinees joined the Riamese effort after making an improvised Riamese flag with blood and Pelican Orchid squeeze, for which the insurgency was deemed the "Orchid Uprising".

Establishment of the Kingdom

Main articles: Kingdom of Anahuac, Cristobál de Anahuac

During the siege of San Jorge Xayacatlán, President Vigil prepared to evacuate the capital and move the republican government to Zaragoza de Seguín. Congress closed its session on 31 May after granting Vigil emergency powers. The Riamese captured the capital on 10 June 1863.

On 16 June the Riamese government's instructions of occupation were set on motion. Under Riamese tutelage, 35 Anahuense citizens were nominated to constitute a Junta Superior de Gobierno who were then tasked with electing a triumvirate that was to serve as the executive of the new government. The three elected were Fulgencio Belarmino, Edelmiro Luján and Pedro Nierman. Occupation forces also to choose 215 Anahuense citizens who together with the Junta Superior were to constitute an Assembly of Notables that was to decide upon the form of government. On 11 July, the Assembly was deposed by conservative group Acción Nacional (Common: National Action) who then imposed their leader as monarch. He took the name Cristobál de Anáhuac and ascended to the newly formed Anahuense throne. While instability was feared by the Riamese, the executive was officially changed into the Regency of the Kingdom of Anahuac with no issues.

Although Republican guerrilla forces in the countryside around the capital counted no victories against the Riamese, they maintained a presence. Tizayuca was captured by imperial forces on 29 July 1863. Republican guerrilla commanders Ángel Lenoci and Damián Escobedo, and others continued to wage warfare against towns occupied by the Riamese.

Imperialist successes

Northern Campaign

Decline of imperial military control

Aftermath

- ↑ Also known as Expedition to Anáhuac in Riamo at the time