President of Morrawia: Difference between revisions

| Line 181: | Line 181: | ||

===Juridical powers and privileges=== | ===Juridical powers and privileges=== | ||

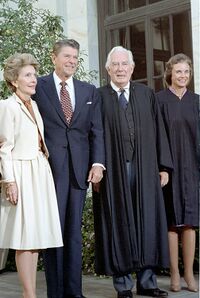

[[File:C4128-22a.jpg|thumb|200px|right|President [[Antonín Worlický]] posing with his two confirmed justices, [[Karel Boril]] and [[Wladimíra Ulrichowá]].]] | [[File:C4128-22a.jpg|thumb|200px|right|President [[Antonín Worlický]] posing with his two confirmed justices, [[Karel Boril]] and [[Wladimíra Ulrichowá]].]] | ||

The president has the power to nominate federal judges, including members of Morrawian courts of appeals and the highest court in the country: the [[Constitutional Tribunal (Morrawia)|Constitutional Tribunal]]. However, these nominations require Senate confirmation, and since ratification of the [[41st Amendment to the Morrawian Constitution| | The president has the power to nominate federal judges, including members of Morrawian courts of appeals and the highest court in the country: the [[Constitutional Tribunal (Morrawia)|Constitutional Tribunal]]. However, these nominations require Senate confirmation, and since ratification of the [[41st Amendment to the Morrawian Constitution|Fourty-first Amendment]] in 1988, special [[Judicial Selection Commission]] is needed too, before they may take office. This commission has largely depoliticized the whole process, encouraging presidents to nominate clearly competent, non-partisan judges. Securing both approvals can provide a major obstacle for presidents who wish to orient the federal judiciary toward a particular ideological stance. When nominating judges to Morrawian district courts, presidents often respect the long-standing tradition of senatorial courtesy. Presidents may also grant pardons and reprieves. Presidents also often grant pardons shortly before leaving office. This is usually seen as highly controversial and frowned upon by the people. | ||

Two doctrines concerning executive power have developed that enable the president to exercise executive power with a degree of autonomy. The first is executive privilege, which allows the president to withhold from disclosure any communications made directly to the president in the performance of executive duties. [[Tristan Palacký]] first claimed the privilege when [[Federal Congress (Morrawia)|Federal Congress]] requested to see Chief Justice notes from an unpopular treaty negotiation with the Royalists. Enshrined in the Constitution or any other law, Palacký's action was a first of its kind. When Pawelský tried to use executive privilege as a reason for not turning over subpoenaed evidence to Federal Congress during the [[Avispa scandal]], the Constitutional Tribunal ruled in [[Republic of Morrawia v. Pawelský]], that executive privilege did not apply in cases where a president was attempting to avoid criminal prosecution. When Antonín Worlický attempted to use executive privilege regarding his sexual scandal, the Constitutional Tribunal ruled in [[Worlický v. Kasír]], that the privilege also could not be used in civil suits. These cases established the legal precedent that executive privilege is valid, and over the years, these decisions were more or less codified and specified. Additionally, federal courts have allowed this privilege to radiate outward and protect other executive branch employees but have weakened that protection for those executive branch communications that do not involve the president. | Two doctrines concerning executive power have developed that enable the president to exercise executive power with a degree of autonomy. The first is executive privilege, which allows the president to withhold from disclosure any communications made directly to the president in the performance of executive duties. [[Tristan Palacký]] first claimed the privilege when [[Federal Congress (Morrawia)|Federal Congress]] requested to see Chief Justice notes from an unpopular treaty negotiation with the Royalists. Enshrined in the Constitution or any other law, Palacký's action was a first of its kind. When Pawelský tried to use executive privilege as a reason for not turning over subpoenaed evidence to Federal Congress during the [[Avispa scandal]], the Constitutional Tribunal ruled in [[Republic of Morrawia v. Pawelský]], that executive privilege did not apply in cases where a president was attempting to avoid criminal prosecution. When Antonín Worlický attempted to use executive privilege regarding his sexual scandal, the Constitutional Tribunal ruled in [[Worlický v. Kasír]], that the privilege also could not be used in civil suits. These cases established the legal precedent that executive privilege is valid, and over the years, these decisions were more or less codified and specified. Additionally, federal courts have allowed this privilege to radiate outward and protect other executive branch employees but have weakened that protection for those executive branch communications that do not involve the president. | ||

Latest revision as of 09:27, 25 November 2024

| President of the Republic of Morrawia | |

|---|---|

| Prezident Morawské republiky | |

| |

| |

| Style |

|

| Type | |

| Abbreviation | POTROM (Common) PMR (Morrawian) |

| Member of | |

| Residence | National House |

| Seat | Králowec, F.D. |

| Appointer | Popular vote or via succession |

| Term length | Four years, renewable once |

| Constituting instrument | Constitution of Morrawia |

| Formation | March 1, 1836 |

| First holder | Tristan Palacký |

| Salary | ₮815,000 per year |

| Website | www |

The president of Morrawia, officially the president of the Republic of Morrawia, is the head of state and head of government of the Republic of Morrawia. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the Morrawian Armed Forces.

The power of the presidency has grown substantially since the first president, Tristan Palacký, took office in 1836. While presidential power has ebbed and flowed over time, the presidency has played an increasingly significant role in Morrawian political life since the beginning of the 20th century, carrying over into the 21st century with notable expansions during the presidencies of Karel Tusar and Josef Sokol. In modern times, the president is one of the world's most powerful political figures. As the leader of the nation with the an increasing economy by nominal GDP, the president possesses significant domestic and international hard and soft power. For much of the 20th century, especially during the Era of Civil Wars, the Morrawian president was often called "free world president", given Morrawia´s usual international stance as a supporter of free, independent, democratic and capitalist nations.

Article III of the Constitution establishes the executive branch of the federal government and vests executive power in the president. The power includes the execution and enforcement of federal law and the responsibility to appoint federal executive, diplomatic, regulatory, and judicial officers. Based on constitutional provisions empowering the president to appoint and receive ambassadors and conclude treaties with foreign powers, and on subsequent laws enacted by the Federal Congress, the modern presidency has primary responsibility for conducting Morrawian foreign policy. The role includes responsibility for directing the the Morrawian military, which has a substantial nuclear arsenal.

The president also plays a leading role in federal legislation and domestic policymaking. As part of the system of separation of powers, Article III of the Constitution gives the president the power to sign or veto federal legislation. Since modern presidents are typically viewed as leaders of their political parties, major policymaking is significantly shaped by the outcome of presidential elections, with presidents taking an active role in promoting their policy priorities to members of the Federal Congress who are often electorally dependent on the president. In recent decades, presidents have also made increasing use of presidential directives, agency regulations, and judicial appointments to shape domestic policy.

The president is elected directly through the popular vote to a four-year term, along with the vice president. Under the Thirty-first Amendment, ratified in 1942, no person who has been elected to two presidential terms may be elected to a third. In addition, six vice presidents have become president by virtue of a president's intra-term death, formal removal or resignation with a total of two presidents dying in office from an ilness, one from assassination, two were removed from office following an impeachment trial and one president resigned from office on his own accords. In all, 34 individuals have served 34 presidencies spanning 202 years of history. Marcel Pelikán is the 34th and current president of Morrawia, having assumed office on April 15, 2024.

History and development

Origins

On 21st August 1822, the National Assembly of Morrawia convened in Torín, marking a pivotal moment in the nation's history. This assembly included notable politicians, sympathetic aristocracy, and other prominent figures of Morrawian public life, alongside the elitist group known as the "August Men". This group was centered around Tristan Palacký and his brother Emanuel, both considered founding fathers of republican Morrawia. The assembly officially declared the Republic of Morrawia, emphasizing their commitment to "ensure a stable future for generations to come and freedom, liberty, and fair justice for all citizens of Morrawia". The so-called People´s Declaration completed before the end of the revolution laid the foundation for the Articles of the Republic, and later the Bill of Rights of Morrawia.

Tristan Palacký, the first president of the Republic of Morrawia, served three terms from 1836 to 1848. He was unaffiliated with any party during his first term but joined Republican Union Party later, party created by his fellow founding fathers. His administration was marked by significant efforts to address the economic stagnation, political chaos, and unresolved colonial questions that plagued the nation. During his term and three other RUP presidents: Boleslaw Keiser, Edward Soukup and Jan Rýnský, many precedents and system were established, that Morrawia uses to this day. Palacký´s leadership was instrumental in restoring Morrawia's prominence on the world stage. Under his guidance, the administration fostered economic revitalization through industrialization, the expansion of the railway system, and the promotion of international trade.

A notable aspect of Palacký's presidency was the influx of former colonial subjects into Morrawia. Reflecting his humanist beliefs, Palacký famously stated that these individuals "have as much right to live happy and fulfilling lives as any white Morrawian man". Despite this, many historians today atribute him racist and nationalistic views, that would for example shape his relationship with his German states.

In 1837, Morrawian Bill of Rights was ratified combining basic principles of the revolution into one paper. This paper has to this day major influence, especially on the judiciary decisions in the country.

During the latter half of the 19th century, Morrawia underwent substantial constitutional reforms to address its evolving needs. A total of 18 constitutional amendments were ratified, addressing the nation’s need for constant improvement. The latter half of the 19th century saw Morrawia grappling with economic stagnation and the societal issues such as slavery and voting rights. Administrations responded by investing in infrastructure projects, promoting industrialization, and establishing trade agreements with neighbouring countries.

Despite these efforts, even this era wasn´t without scandals. The most prominent one would be the impeachment and removal of the 3rd President of the Republic of Morrawia, Edward Soukup.

1860-1900

After 12 years of continuous leadership, the Republican Union Party lost the 1860 presidential election to Lubomír Hant, a candidate from the National Democratic Party. This was the surprising victory, as RUP put out a strong candidate that year and expected to win easily. Hant was also the first president to die in office of tuberculosis. The two parties were the two sole political entities in national Morrawian politics. His vice president Benedikt Augustýn won both his own first election and his reelection. He is today the most remembered by deescalating the situation around slavery and subsequently prohibiting it by pushing for the 18th Amendment. The next 2 presidents: Robert Marwan (1876-1884, Republican Union Party) and Jiṙí Buṡ (1884-1892, National Democratic Party) were known as "Presidents of compromise" for their skilled negotiating work with the Federal Congress. Republican Union Party won the presidency with Adrian Nowý's victory in 1892, internal divisions and external pressures weakened the party over time. Nowý's term, from 1892 to 1896, saw attempts to modernize the party and address internal conflicts, but these efforts proved insufficient, however these were unsucessful and he would become the last president of that party. The party dissolved at the turn of the century into several smaller factions, with the most notable successor being the Republican Party, which continues to function today.

In 1896, Wilhelm Lipowski became the first liberal president of Morrawia. His administration, lasting until 1900, was responsible for implementing several customer-friendly and worker-friendly policies. Lipowski's government introduced early labor rights protections, regulations on working hours, and improved safety standards in factories. These reforms laid the groundwork for Morrawia's later social and economic policies.

Beginnings of the imperial presidency

The ascendancy of Pawel Záworský in 1900, the first president from the newly formed Republican Party, who initiated a period known as the Septennial of Reforms, led further toward what historians now describe as the Imperial presidency. Backed by enormous Republican majorities in the Federal Congress and public support for major change, Záworský's Great Nation program dramatically increased the size and scope of the federal government, including more executive agencies. The traditionally small presidential staff was greatly expanded, with the Executive Office of the President of Morrawia being created in 1901, none of whom require Senate confirmation. During his term (1900-1904), Morrawia saw the introduction of groundbreaking social security guarantees, massive anti-monopoly laws, and expanded workers' rights. Early forms of pensions and insurance were created, providing a safety net for the nation's workforce. Two significant constitutional amendments marked this period of reform. The 19th Amendment, ratified in 1902, abolished the electoral college, introducing a new electoral system that allowed for more direct representation of the populace. In 1905, the 20th Amendment granted women the right to vote, a landmark achievement in Morrawia's history that followed intense activism and advocacy by women's suffrage groups.

Wáclaw Morawċík, one of the most consequential presidents in Morrawian history, succeeded Záworský. Serving from 1904 to 1911, Morawċík initially planned a modest foreign policy but later decided to join the Great War. This decision was highly controversial and almost cost him his second term. However, Morrawia emerged on the winning side, which ultimately bolstered his legacy. President Morawċík marked a significant departure from the stance of mostly isolationist stance. The war's aftermath saw Morrawia emerge as a more prominent player on the international stage, influencing its foreign policy direction in subsequent decades. Domestically, Morawċík continued the reformist agenda, further expanding social security and workers' rights. He became the second Morrawian president to die in office in 1911, experiencing a sudden stroke. His successor, Karel Tusar, serving from 1911 to 1920, is regarded by many historians as one of Morrawia's greatest presidents. His administration is best known for the signing of the Direktiwa policy into law, also known as the "Tusar Doctrine". This policy significantly increased government involvement in the economy, setting the stage for much of the 20th century's economic landscape. Tusar's government implemented state control over key industries, increased public spending on infrastructure, and established social programs aimed at reducing poverty and inequality.

This turbulent times began under the presidency of Herbert Klimeṡ, who served from 1920 to 1924 as a representative of the National Democrats. Klimeṡ's administration, was seen as the break from the Liberal-Republican monopoly. With his mostly centrist policies, Morrawia saw unprecedented cooperation in the Federal Congress, which saw many of the most consequential legislation up to that point, being passed with wide bipartisan and even multi partisan support, such as the Heavy Industry Safety Act of 1922, marking one of the first major safety legislations in that sector. Klimeṡ decided to not seek the second term, due to the death of his late-wife right by the end of his first term.

Rostislaw Nowotný, the last president from the National Democrats (1924-1928), initially gained popularity through his charismatic leadership and ambitious economic policies, such as the 1927 "Iron Pact" aimed at industrial modernization, through record-breaking federal funds. However, his administration was marred by scandals like the "Golden Exchange Affair", which revealed embezzlement of state funds, leading to public disillusionment and the eventual downfall of his party. As the public's disillusionment with the National Democrats reached its peak, the Republicans seized power under Antonín Sád in 1928. However, Sád's administration quickly became embroiled in controversies of its own, most notably the 1930 Smoke Room Agreement, which ended the long blockade of Cordomonivence but was widely seen as a betrayal of national interests. The agreement, coupled with mounting accusations of corruption and abuse of power, led to Sád's impeachment and resignation in 1931.

Christoph Steinmayer, who took over after Sád's resignation, attempted to stabilize the situation, but his administration was tainted by its association with the scandals of the preceding years. Steinmayer's decision to pardon Sád only deepened public cynicism, and by the time he left office in 1932, the era had left a lasting scar on Morrawian democracy.

The 1920s and 30s revealed not only the moral failings of individual leaders but also the severe structural weaknesses in Morrawia's democratic system. The inability of institutions, mainly Federal Congress to effectively check the excesses of the executive branch led to a widespread loss of public trust and called into question the very foundations of the republic. In response, the immediate aftermath of this era saw a wave of reforms aimed at strengthening democratic institutions. Numerous laws and constitutional amendments were enacted to improve transparency, enhance the separation of powers, and establish stricter oversight mechanisms.

While the era did not descend into outright dictatorship or other authoritarian regime, it brought Morrawia perilously close to fascism. The concentration of power, nationalist rhetoric, and disregard for established political norms alarmed many Morrawians and set a precedent for political caution in subsequent administrations. One of the most significant outcomes of this era was the eventual establishment of a two-party system in Morrawia. The political chaos and disillusionment with this time led to the rise of the Liberal Party and the Republican Party, now reborn and barely surviving as the dominant forces in Morrawian politics, providing a more stable and balanced political environment.

Contemporary Period

Since 1932, the political landscape of Morrawia underwent a significant transformation, cementing the nation's status as a two-party state. The Liberal Party and the Republican Party emerged as the dominant political forces, shaping Morrawia's governance for decades to come. These parties significantly moderated their policies following the previous era as to appeal to wider array of voters.

The new era began with the presidency of Eduard Palacký, the great-grandson of Tristan Palacký, a founding father of the Republic of Morrawia. Eduard's tenure marked the solidification of Liberal values in Morrawian politics, emphasizing national pride, mild liberal social policies, and a free-market economy.

President Karel Abrahám, elected in 1940, as the first Republican post-scandal era, is regarded by many as father of the modern Republican Party for his wide-reaching efforts to rebrand the party into a more moderate party with moderate conservative values and evolving outlook on things like regulation, big-business and more, while still being clear-cut capitalist in nature. A national hero, general is credited with saving the party from near destruction.

From 1952 to 1964, Morrawia saw the leadership of the Sada brothers, Klement and Andrej, both members of the Liberal Party. Their presidencies were characterized by progressive social policies and a continuation of the Direktiwa policy, which involved significant government intervention in the economy. This period saw economic growth and social reform in the form of Civil rights movement but also set the stage for future political turmoil.

The assassination of Republican President Karl Walmark in 1964 during an attempted coup marked a dark chapter in Morrawian history. Walmark's death, the only presidential assassination in Morrawia, triggered a big political shift. Both parties moved further to the right, leading to the gradual phasing out of Direktiwa. The economic policy morphed into Indirektiwa, a neoliberal approach that reduced government intervention in favor of free-market principles. This ideological shift reached its zenith during the 1980s under the Republican rule, with both parties adopting right-wing staunch economic policies.

The 1990s brought prosperity to Morrawia, but the political climate remained dynamic. In 1996, Mariána Turmenská became the first woman president. Despite initial popularity, her term ended in 2000 with a decline in public approval, paving the way for a Republican resurgence.

In 2000, Republican Josef Sokol was elected president, marking the first Republican leadership in the 21st century. Sokol's presidency focused on addressing increased terrorism and economic challenges. His policies shifted the Republican Party further to the centre on some issues, and right to other, while pushing the Liberals towards the left generally. Sokol's popularity is celebrated to this day and he remains one of the most popular president's in Morrawian history. He was succeeded by René Denár, first black president in Morrawian history.

Today, the political scene in Morrawia features the Republicans as a center-right party and the Liberals as a center-left party. The current president, Marcel Pelikán, is notable for his left-leaning stance within the Liberal Party, challenging the party's traditional establishment and advocating for more progressive policies.

Legislative powers

Article II of the Constitution vests all lawmaking power in the Federal Congress's hands, and prevents the president (and all other executive branch officers) from simultaneously being a member of the Federal Congress. Nevertheless, the modern presidency exerts significant power over legislation, both due to constitutional provisions and historical developments over time.

Signing and vetoing bills

The president's most significant legislative power derives from the Presentment Clause, which gives the president the power to veto any bill passed by the Federal Congress. While the Federal Congress can override a presidential veto, it requires a two-thirds vote of both houses, which is usually very difficult to achieve except for widely supported bipartisan legislation. The framers of the Constitution feared that Congress would seek to increase its power, so giving the elected president a veto was viewed as an important check on the legislative power. While Tristan Palacký believed the veto should only be used in cases where a bill was unconstitutional, it is now routinely used in cases where presidents have policy disagreements with a bill. The veto – or threat of a veto – has thus evolved to make the modern presidency a central part of the Morrawian legislative process.

Specifically, under the Presentment Clause, once a bill has been presented by the Federal Congress, the president has three options:

- sign the legislation within ten days, excluding Sundays, the bill becomes law.

- veto the legislation within the above timeframe and return it to the house of Congress from which it originated, expressing any objections, the bill does not become law, unless both houses of Congress vote to override the veto by a two-thirds vote.

- take no action on the legislation within the above timeframe — the bill becomes law, as if the president had signed it, unless the Federal Congress is adjourned at the time, in which case it does not become law, which is known as a pocket veto.

In 1996, the Federal Congress attempted to enhance the president's veto power with the Line Item Veto Act. The legislation empowered the president to sign any bill into law while simultaneously striking certain items within the bill. Federal Congress could then repropose that particular item. If the president then vetoed the new legislation, Federal Congress could override the veto by its ordinary means, a two-thirds vote in both houses. In Turmenská v. City of Veligrad, the Morrawian Constitutional Tribunal ruled such a legislative alteration of the veto power to be unconstitutional.

Setting the agenda

For most of Morrawian republican history, candidates for president have sought election on the basis of a promised legislative agenda. Article III requires the president to recommend such measures to the Federal Congress which the president deems "necessary and expedient". This is done through the constitutionally-based State of the Union address, which usually outlines the president's legislative proposals for the coming year, and through other formal and informal communications with the Federal Congress.

The president can be involved in crafting legislation by suggesting, requesting, or even insisting that the Federal Congress enact laws he believes are needed. Additionally, he can attempt to shape legislation during the legislative process by exerting influence on individual members of the Federal Congress. Presidents possess this power because the Constitution specifically defines it.

The president or other officials of the executive branch may draft legislation and then ask senators or representatives to introduce these drafts into the Federal Congress. Additionally, the president may attempt to have Federal Congress alter proposed legislation by threatening to veto that legislation unless requested changes are made.

Promulgating regulations

Many laws enacted by the Federal Congress do not address every possible detail, and either explicitly or implicitly delegate powers of implementation to an appropriate federal agency. As the head of the executive branch, presidents control a vast array of agencies that can issue regulations with little oversight from the Federal Congress.

In the 20th century, critics charged that too many legislative and budgetary powers that should have belonged to the Federal Congress had slid into the hands of presidents. One critic charged that presidents could appoint a "virtual army of 'czars'—each wholly unaccountable to the Federal Congress yet tasked with spearheading major policy efforts for the National House". Presidents have been criticized for making signing statements when signing congressional legislation about how they understand a bill or plan to execute it. This practice has been criticized by the Morrawian Bar Association as unconstitutional. Conservative commentators often talk about an "increasingly swollen executive branch" and "the eclipse of the Federal Congress".

Convening and adjourning the Federal Congress

To allow the government to act quickly in case of a major domestic or international crisis arising when the Federal Congress is not in session, the president is empowered by Article III of the Constitution to call a special session of one or both houses of the Federal Congress. Since Boleslaw Keiser first did so in 1850, the president has called the full Federal Congress to convene for a special session on numerous occasions. In practice, the power has fallen into disuse in the modern era as the Federal Congress now formally remains in session year-round, convening pro forma sessions every three days even when ostensibly in recess. Correspondingly, the president is authorized to adjourn the Federal Congress if the House and Senate cannot agree on the time of adjournment. No president has ever had to exercise this power.

Executive powers

The president is head of the executive branch of the federal government and is constitutionally obligated to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed". The executive branch has over five million employees, including the military.

Administrative powers

Presidents make political appointments. An incoming president may make up to 3,000 upon taking office, 1000 of which must be confirmed by the Morrawian Senate. Ambassadors, members of the Council of Ministers, and various officers, are among the positions filled by presidential appointment with Senate confirmation.

The power of a president to fire executive officials has long been a contentious political issue. Generally, a president may remove executive officials at will. However, Federal Congress can curtail and constrain a president's authority to fire commissioners of independent regulatory agencies and certain inferior executive officers by statute.

To manage the growing federal bureaucracy, presidents have gradually surrounded themselves with many layers of staff, who were eventually organized into the Executive Office of the President of Morrawia. Within the Executive Office, the president's innermost layer of aides, and their assistants, are located in the National House Office.

The president also possesses the power to manage operations of the federal government by issuing various types of directives, such as presidential proclamations, presidential decrees and federal orders. When the president is lawfully exercising one of the constitutionally conferred presidential responsibilities, the scope of this power is broad. Even so, these directives are subject to judicial review by Morrawian federal courts, which can find them to be unconstitutional. Federal Congress can overturn a federal order or a decree (such as declaring national emergency etc.) through legislation or joint motion.

Foreign affairs

Article III requires the president to "receive Ambassadors of other nations and other representatives, having power to decide upon a national foreign policy." This clause, known as the Reception Clause, means that the president possesses broad power over matters of foreign policy, and to provide support for the president's exclusive authority to grant recognition to a foreign government. The Constitution also empowers the president to appoint Morrawian ambassadors, and to propose and chiefly negotiate agreements between Morrawia and other countries. Such agreements, upon receiving the advice and consent of the Morrawian Senate (by a two-thirds majority vote), become binding with the force of federal law.

While foreign affairs has always been a significant element of presidential responsibilities, advances in technology since the Constitution's adoption have increased presidential power. Where formerly ambassadors were vested with significant power to independently negotiate on behalf of Morrawia, presidents now routinely meet directly with leaders of foreign countries.

Commander-in-chief

One of the most important of executive powers is the president's role as commander-in-chief of the Morrawian Armed Forces. The power to declare war is constitutionally vested in the Federal Congress, but the president has ultimate responsibility for the direction and disposition of the military. The exact degree of authority that the Morrawian Constitution grants to the president as commander-in-chief has been the subject of much debate throughout history, with the Federal Congress at various times granting the president wide authority and at others attempting to restrict that authority. The framers of the Constitution took care to limit the president's powers regarding the military as to not cause the apparatus to fall into the hands of a tyrant.

In the modern era, pursuant to the War Powers Resolution, Federal Congress must authorize any troop deployments longer than 60 days. Additionally, Federal Congress provides a check to presidential military power through its control over military spending and regulation. Presidents have historically initiated the process for going to war, but critics have charged that there have been several conflicts in which presidents did not get official declarations.

The amount of military detail handled personally by the president in wartime has varied greatly. Tristan Palacký, the first Morrawian president, firmly established military subordination under civilian authority. In 1845, Palacký used his constitutional powers to assemble 10,000 militia to quell the Royal Rebellion, a conflict in western Sollandy involving armed farmers and imperial sympathizers who refused to join and acknowledge the new republic. According to historian Josef Eliáṡ, this was the "first and only time a sitting Morrawian president led troops in the field". During the Great War, president Morawċík was deeply involved in overall strategy and in day-to-day operations. This meant the domestic policy would have to go aside.

The present-day operational command of the Armed Forces is delegated to the Ministry of Defense and is normally exercised through the Minister of defense. The chairman of the Joint Staff of the Armed Forces and the Combatant Commands assist with the operation as outlined in the presidentially approved Unified Command Plan (UCP).

Juridical powers and privileges

The president has the power to nominate federal judges, including members of Morrawian courts of appeals and the highest court in the country: the Constitutional Tribunal. However, these nominations require Senate confirmation, and since ratification of the Fourty-first Amendment in 1988, special Judicial Selection Commission is needed too, before they may take office. This commission has largely depoliticized the whole process, encouraging presidents to nominate clearly competent, non-partisan judges. Securing both approvals can provide a major obstacle for presidents who wish to orient the federal judiciary toward a particular ideological stance. When nominating judges to Morrawian district courts, presidents often respect the long-standing tradition of senatorial courtesy. Presidents may also grant pardons and reprieves. Presidents also often grant pardons shortly before leaving office. This is usually seen as highly controversial and frowned upon by the people.

Two doctrines concerning executive power have developed that enable the president to exercise executive power with a degree of autonomy. The first is executive privilege, which allows the president to withhold from disclosure any communications made directly to the president in the performance of executive duties. Tristan Palacký first claimed the privilege when Federal Congress requested to see Chief Justice notes from an unpopular treaty negotiation with the Royalists. Enshrined in the Constitution or any other law, Palacký's action was a first of its kind. When Pawelský tried to use executive privilege as a reason for not turning over subpoenaed evidence to Federal Congress during the Avispa scandal, the Constitutional Tribunal ruled in Republic of Morrawia v. Pawelský, that executive privilege did not apply in cases where a president was attempting to avoid criminal prosecution. When Antonín Worlický attempted to use executive privilege regarding his sexual scandal, the Constitutional Tribunal ruled in Worlický v. Kasír, that the privilege also could not be used in civil suits. These cases established the legal precedent that executive privilege is valid, and over the years, these decisions were more or less codified and specified. Additionally, federal courts have allowed this privilege to radiate outward and protect other executive branch employees but have weakened that protection for those executive branch communications that do not involve the president.

The state secrets privilege allows the president and the executive branch to withhold information or documents from discovery in legal proceedings if such release would harm national security. Precedent for the privilege arose early in the mid-19th century when Boleslaw Keiser refused to release military documents in the treason trial of several high ranking officials, when the Constitutional Tribunal dismissed a case brought by a former Union spy. However, the privilege was not formally recognized in the Morrawian Code until the passage of National Security Privilege Act of 1905, Secret Documents Act of 1925, Classified Information Protection Act of 1930 and the Constitutional Tribunal decision Republic of Morrawia v. Hejrowský, where it was held to be a civil law evidentiary privilege. By this mid-century, Morrawia was using a mix of civil and common law in all of its civil and criminal proceedings. Before the Years of Terror, use of the privilege had been rare, but increasing in frequency. Since 2001, the government has asserted the privilege in more cases and at earlier stages of the litigation, thus in some instances causing dismissal of the suits before reaching the merits of the claims. Critics of the privilege claim its use has become a tool for the government to cover up illegal or embarrassing government actions.

Leadership roles

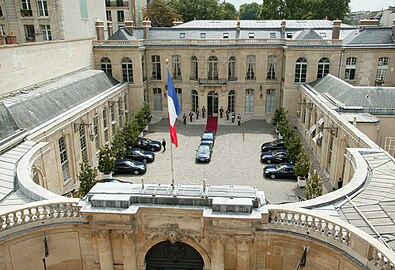

Head of state

As head of state, the president represents the Morrawian government to its own people and represents the nation to the rest of the world. For example, during a state visit by a foreign head of state, the president typically hosts a State Arrival Ceremony held on the South Lawn, a custom begun by Klement Sada in 1952. This is followed by a state dinner given by the president which is held in the State Dining Room later in the evening.

As a national leader, the president also fulfills many less formal ceremonial duties, such throwing out the ceremonial first pitch, handing out cookies on the South Lawn to scouts, choosing any school in any state and visiting in on the first their of class, etc.

Other presidential traditions are associated with Morrawian holidays. Edward Soukup began in 1852 the first National House Tag for local children. Beginning in 1945, during the Karel Abrahám administration, every Victory Day the president heads the annual National Victory Day Presentation held at the National House with educational presentations and attractions for children.

Presidential traditions also involve the president's role as head of government. Many outgoing presidents since Wilhelm Lipowski traditionally give advice to their successor during the presidential transition. Antonín Worlický and his successors have also left a private message and one small souvenir of their choice on the desk of the Resolute Office on Inauguration Day for the incoming president.

The modern presidency holds the president as one of the nation's premier celebrities. Some argue that images of the presidency have a tendency to be manipulated by administration public relations officials as well as by presidents themselves. One critic described the presidency as "propagandized leadership" which has a "mesmerizing power surrounding the office". Administration public relations managers staged carefully crafted photo-ops of smiling presidents with smiling crowds for television cameras.

Head of party

The president is typically considered to be the head of their political party. Since the entire House of Representatives and at least one-third of the Senate is elected simultaneously with the president, candidates from a political party inevitably have their electoral success intertwined with the performance of the party's presidential candidate. The coattail effect, or lack thereof, will also often impact a party's candidates at state and local levels of government as well. However, there are often tensions between a president and others in the party, with presidents who lose significant support from their party's caucus in the Federal Congress generally viewed to be weaker and less effective.

Major world leader

With the rise of Morrawia as a major power in the 20th century, and the country having one of the world's largest economies into the 21st century, the head of state is typically viewed as a major global leader. The position of Morrawia as a leading member of major international alliance, Sunadic Treaty Organization, and the country's strong relationships with other wealthy or democratic nations, have led to the moniker that the head of state is the "free world president".

Selection process

Eligibility

Article III of the Constitution sets three qualifications for holding the presidency. To serve as president, one must:

- be a natural-born citizen of Morrawia;

- be at least 35 years old;

- be a resident in Morrawia for at least 15 years.

A person who meets the above qualifications would, however, still be disqualified from holding the office of president under any of the following conditions:

Having been impeached, convicted and disqualified from holding further public officeincluding the office of the president. Furthermore, no person who swore an oath to support the Morrawian Constitution, and later rebelled against the Republic of Morrawia, is eligible to hold any office. However, this disqualification can be lifted by a two-thirds vote of each house of the Federal Congress. For the longest time, some debate as to whether the clause as written allowed disqualification from the presidential position, or whether it would first require litigation outside of the Federal Congress, existed, though this has been fixed through numerous pieces of legislation delving into this problem.

Under the 31st Amendment, no person can be elected president more than twice. The amendment also specifies that if any eligible person serves as president or acting president for more than two years of a term for which some other eligible person was elected president, the former can only be elected president once.

Campaigns and nomination

The modern presidential campaign begins before the primary elections, which the two major political parties use to clear the field of candidates before their national nominating conventions, where the most successful candidate is made the party's presidential nominee. Typically, the party's presidential candidate chooses a vice presidential nominee, and this choice is rubber-stamped by the convention. The most common previous profession of presidents is lawyer.

Nominees participate in nationally televised debates, and while the debates are usually restricted to the Liberal and Republican nominees, third party candidates may are recently invited more and more. Nominees campaign across the country to explain their views, convince voters and solicit contributions. Much of the modern electoral process is concerned with winning swing states through frequent visits and mass media advertising drives.

Election

The president was elected indirectly by the voters of each state and the Federal District through the Electoral College until it was revoked in 1902 with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the Morrawian Constitution, a body of electors formed every four years for the sole purpose of electing the president and vice president to concurrent four-year terms. As prescribed by Article III, each state was entitled to a number of electors equal to the size of its total delegation in both houses of the Federal Congress.

Upon it´s change, presidential elections have become those of two-round system with only Popular vote decideding winner of the election. Two-round system was put in place to ensure better representation of Morrawians in the candidate. If no candidate gets over 5 percent of the vote in the first round, the second round happens exactly a week after the first one.

Since 1995, voting days for all public offices on the federal level are designated as federal public holidays and people don´t have to work or go to educational facility that day with the passage of the Election Day Act of 1995.

Inauguration

Pursuant to the Seventeenth Amendment, the four-year term of office for both the president and the vice president begins at noon on April 15, in the same year as the presidential election. The first presidential and vice presidential terms with this date, known as Inauguration Day, were the second terms of President Robert Marwan and Vice President Jaromír Kuchta in 1876. Previously, Inauguration Day was on April, 20. As a result of the date change, their first term (1876–80) of both men had been shortened by 5 days.

Before executing the powers of the office, a president is required to recite the presidential Oath of Office, found in Article III, of the Constitution. This is the only component in the inauguration ceremony mandated by the Constitution:

"I, do solemnly swear to faithfully execute the duties of the presidency of the Republic of Morrawia, to defend and uphold the principles enshrined in the Constitution of the Republic of Morrawia, and pledge to sustain the Union, promoting freedom, democracy and welfare of the Morrawian people. So help me God."

Presidents have traditionally placed one hand upon a Bible while taking the oath. Although the oath may be administered by any person authorized by law to administer oaths, presidents are traditionally sworn in by the chief justice of the highest court in the country, Constitutional Tribunal.

Incumbency

Term limits

When the first president, Tristan Palacký, announced in his farewell address regretted taking the third term (second if as of the ratification of the Constitution), he adviced all other high public holders to limit their time in office, thus creating the "two terms then out" precedent. Precedent became tradition, though the first president to publicly embrace the tradition was Lubomír Hant and his immediate successor, Benedikt Augustýn in 1864 and 1876 respectively.

In 1932, after the era of Radical Presidencies, Republican Eduard Palacký was to first to have a more stable term and this established the contemporary period of mostly double-term presidents.

Largely in response to the unprecedented tactics during the radical presidencies, the Thirty-First Amendment was adopted in 1942, encompassing various measures to limit the presidential powers, though some compromises were made. The amendment, amongst other criteria, bars anyone from being elected president more than twice, or once if that person served more than two years (24 months) of another president's four-year term. Karel Abrahám, the president at the time it was submitted to the states by the Federal Congress, was exempted from its limitations. Since becoming operative in 1946, the amendment has been applicable to seven twice-elected presidents: Klement Sada, Mirosław Jaworski, Antonín Worlický, Mariána Turmenská, Josef Sokol, René Denár, and Tomáṡ Slawinský.

Vacancies and succession

Under Section 1 of the Thirty-first Amendment, ratified in 1942, the vice president becomes president upon the removal from office, death, or resignation of the president. Deaths have occurred a number of times, resignation has occurred only once, and removal from office has never occurred.

Before the ratification of the amendment (which clarified the matter of succession), Article III stated that the vice president assumes the "powers and duties" of the presidency in the event of a president's removal, death, resignation, or inability stating they would become "President of the Republic of Morrawia". During the drafting of the constitution, this was a point of contention, with some wanting the vice president to only be "acting president" instead of the actual one.

In the event of a double vacancy, Article II also authorizes the Federal Congress to declare who shall become acting president in the "Case of Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability, both of the president and vice president". The Presidential Succession Act of 1922 provides that if both the president and vice president have left office or are both otherwise unavailable to serve during their terms of office, the presidential line of succession follows the order of: speaker of the House, and then if necessary, the eligible heads of federal executive departments who form the president's cabinet. The cabinet currently has 17 members, of which the minister of foreign affairs is first in line. The other Council ministers follow in the order in which their department was selected, their importance. Those individuals who are constitutionally ineligible to be elected to the presidency are also disqualified from assuming the powers and duties of the presidency through succession. No statutory successor has yet been called upon to act as president. This was slightly changed by the aformentioned 31st Amendment, removing the speaker of the House from the succession process.

Declarations of inability

Under the Thirty-first Amendment, the president may temporarily transfer the presidential powers and duties to the vice president, who then becomes acting president, by transmitting to the speaker of the House and the speaker of the Senate a statement that he is unable to discharge his duties. The president resumes his or her powers upon transmitting a second declaration stating that he is again able. The mechanism has been used by Mirosław Jaworski (once), Marcel Palacký (twice), and Tomáṡ Slawinský (once), each in anticipation of surgery.

The Thirty-first Amendment also provides that the vice president, together with a majority of certain members of the Council of Ministers, may transfer the presidential powers and duties to the vice president by transmitting a written declaration, to the speaker of the House and the speaker of the Senate, to the effect that the president is unable to discharge his or her powers and duties. If the president then declares that no such inability exist, he or she resumes the presidential powers unless the vice president and Council of Ministers make a second declaration of presidential inability, in which case the Federal Congress decides the question.

Removal

Article II of the Constitution allows for the removal of high federal officials, including the president, from office for various crimes, these were highly specific at the time of drafting the constitution and were even expanded upon by the 29th Amendment in 1935. Article Two of the Morrawian Constitution authorizes the House of Representatives to serve as a court with the power to impeach said officials by a majority vote. Article I authorizes the Senate to serve as a court with the power to remove impeached officials from office, by a two-thirds vote to convict.

Four presidents have been impeached by the House of Representatives: Edward Soukup in 1853, Antonín Sád in 1931, Karel Pawelský in 1979 and Antonín Worlický in 1988, with only the first one and the third one mentioned being convicted by the Senate. Additionally, the House Judiciary Committee conducted an impeachment inquiry against Antonín Sád in 1930-1931 and reported five articles of impeachment to the House of Representatives for final action, impeached President Sád, and he later resigned from office.

Circumvention of authority

Controversial measures have sometimes been taken short of removal to deal with perceived recklessness on the part of the president, or with a long-term disability. In some cases, staff have intentionally failed to deliver messages to or from the president, typically to avoid executing or promoting the president to write certain orders. This has ranged from Marcel Palacký's Chief of Staff not transmitting orders to the Cabinet due to the president's heavy drinking, to staff removing memos from René Denár's desk. Decades before the Thirty-first Amendment, in 1922, President Herbert Klimeṡ had a stroke that left him partly incapacitated. First lady Edita Klimeṡowá kept this condition a secret from the public for a while, and controversially became the sole gatekeeper for access to the president (aside from his doctor), assisting him with paperwork and deciding which information was "important" enough to share with him.

Compensation

Since 2001, the president's annual salary has been ₮815,000, along with a: ₮16,000 expense allowance, ₮120,000 nontaxable travel account, and ₮20,000 entertainment account. The president's salary is set by the Federal Congress, and under Article II of the Morrawian Constitution, any increase or reduction in presidential salary cannot take effect before the next presidential term of office.

Residence

The National House in Králowec, F.D. is the official residence of the president. The site was selected by Tristan Palacký, and the cornerstone was laid in 1830. Every president since Tristan Palacký (in 1838) has lived there. At various times in Morrawian history, it has been known as the "Presidential Palace", the "President's House", and the "Executive Mansion". Wáclaw Morawċík officially gave the National House its current name in 1905. The federal government pays for state dinners and other official functions, but the president pays for personal, family, and guest dry cleaning and food.

Camp Lény, officially titled Naval Support Facility Jeseniṡtė, a mountain-based military camp in Theodor County, Fallaine, is the president's country residence. A place of solitude and tranquility, the site has been used extensively to host foreign dignitaries since the 1940s.

Maroon House, located next to the Lipowski Square, serves as the president's official guest house and as a secondary residence for the president if needed. Four interconnected, 19th-century houses with a combined floor space exceeding 6,500 square meters (70,000 ft2) comprise the property.

- Presidential residences

National House, the official residence

Camp Lény in Theodor County, Fallaine, the official retreat

Bordaṅ Fort in Bordaṅ County, Sollandy, the official summer retreat

Maroon House, the official guest house

Travel

The primary means of long-distance air travel for the president is one of two identical PAC S-05 aircrafts, which are extensively modified PAC 101 airliners and are referred to as Air Force One while the president is on board (although any Morrawian Air Force aircraft the president is aboard is designated as "Air Force One" for the duration of the flight). In-country trips are typically handled with just one of the two planes, while overseas trips are handled with both, one primary and one backup. The president also has access to smaller Air Force aircraft, most notably the PAC E-35, which are used when the president must travel to airports that cannot support a jumbo jet. Any civilian aircraft the president is aboard is designated Commander One for the flight.

For short-distance air travel, the president has access to a fleet of Morrawian Marine Corps helicopters of varying models, designated Marine One when the president is aboard any particular one in the fleet. Flights are typically handled with as many as five helicopters all flying together and frequently swapping positions as to disguise which helicopter the president is actually aboard to any would-be threats.

For ground travel, the president uses the presidential state car, which is an armored limousine designed to look like a Carras sedan, but built on a truck chassis. The Morrawian Presidential Service operates and maintains the fleet of several limousines. The president also has access to two armored motorcoaches, which are primarily used for touring trips.

- Presidential transportation

The presidential limousine, dubbed "The Lion"

The presidential plane, called Air Force One when the president is on board

The presidential helicopter, known as Marine One when the president is aboard

Protection

The Morrawian Presidential Service is charged with protecting the president and the first family. As part of their protection, presidents, first ladies, their children and other immediate family members, and other prominent persons and locations are assigned Presidential Service codenames. The use of such names was originally for security purposes and dates to a time when sensitive electronic communications were not routinely encrypted; today, the names simply serve for purposes of brevity, clarity, and tradition.

Post-presidency

Activities

Some former presidents have had significant careers after leaving office. Prominent examples include Wilhelm Lipowski's tenure as chief justice of the Republic of Morrawia and Eduard Palacký's work on foreign missions for several administrations. Two former presidents served in the Federal Congress after leaving the National House: Andrej Sada was elected to the House of Representatives, serving there for 24 years, and more recently René Denár returned to the Senate in 2018. Some ex-presidents were very active, especially in international affairs, most notably Jan Rýnský, Wáclaw Morawċík, Karel Tusar, and Anton Auer.

Presidents may use their predecessors as emissaries to deliver private messages to other nations or as official representatives of the Republic of Morrawia to state funerals and other important foreign events. Gustaw Fabián made multiple foreign trips to countries including Riamo and other countries and was lauded as an elder statesman, despite his rather weak reputation as president. Mariána Turmenská, first and only woman to ever become president, has become a global human rights campaigner, international arbiter, and election monitor, as well as a recipient of many international prizes. Josef Sokol has also worked as an informal ambassador. During his presidency, René Denár called on former Presidents Turmenská and Sokol to assist with humanitarian and societal efforts after the series of bombings around the country during the Years of Terror. President Slawinský followed suit by asking President Denár to lead efforts to aid in international efforts throughout his tenure.

Sokol was active politically since his presidential term ended, working with his wife Klementýna on her 2016 presidential bids. Slawinský was also active politically since his presidential term ended, staunchly supporting his former vice president Marcel Pelikán on his 2024 election campaign.

Pension and other benefits

The Former Presidents Act (FPA), enacted in 1950, grants lifetime benefits to former presidents and their widows, including a monthly pension, medical care in military facilities, premium health insurance, and Presidential Service protection; also provided is funding for a certain number of staff and for office expenses. The act has been amended several times to provide increases in presidential pensions and in the allowances for office staff. The FPA excludes any president who was removed from office by impeachment.

According to a 2008 report by the Congressional Research Service:

"Chief executives leaving office prior to 1950 often entered retirement pursuing various occupations and received little to no federal assistance. When industrialist Adrián Koreṡ announced a plan in 1912 to offer ₮100,000 annual pensions to former Presidents, many Members of the Federal Congress deemed it inappropriate that such a pension would be provided by a private corporation executive. That same year, legislation was first introduced to create presidential pensions, but it was severely compromised upon and the result was not favourable to anyone. In 1950, such legislation was considered by the Federal Congress because of former President Karel Abrahám's financial limitations in hiring an office staff."

The pension has increased numerous times with congressional approval. Retired presidents receive a pension based on the salary of the current administration's cabinet ministers, which was ₮549,032 per year in 2012. Former presidents who served in the Federal Congress may also collect congressional pensions. The act also provides former presidents with travel funds and franking privileges.

Prior to 1997, all former presidents, their spouses, and their children until age 16 were protected by the Presidential Service until the president's death. In 1997, Federal Congress passed legislation limiting Presidential Service protection to no more than 15 years from the date a president leaves office. On January 10, 2007, President Sokol signed legislation reinstating lifetime Presidential Service protection for him, Mariána Turmenská, and all subsequent presidents. A first spouse who remarries is no longer eligible for Presidential Service protection.

Presidential centres

Every president since Eduard Palacký has created a repository known as a presidential cultural centre for preserving and making available his papers, records, and other documents and materials. Completed libraries, museums and other buildings are deeded to and maintained by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), the initial funding for building and equipping each must come from private, non-federal sources. There are currently fifteen presidential cultural centres in the NARA system. There are also presidential cultural centres maintained by state governments and private foundations and Universities of Higher Education, including:

The Benedikt Augustýn Presidential Library and Museum, which is run by the Elbennau, The Gustaw Fabián Presidential Centre, which is run by Northern Methodist University, The Karel Abrahám Presidential Cultural Exposition, which is run by Palacia State University, and The Klement Sada Presidential Library and Museum, which is run by the University of Dalmate at Jegowowo.

Several former presidents have overseen the building and opening of their own presidential cultural centres. Some even made arrangements for their own burial at the site. Several presidential cultural centres contain the graves of the president they document. These gravesites are open to the general public.

Political affiliation

Political parties have dominated Morrawian politics for most of the nation's modern republican history. Though the Founding Fathers, especially the Palacký brothers generally spurned political parties as divisive and disruptive, and their rise had not been welcomed when the Morrawian Constitution was drafted in 1836, organized political factions developed in Morrawia already in that time nonetheless. They evolved from political factions, which appeared largely in the Imperial Council of Deputies and stayed strong even after the Federal government came into existence. Those who supported the Palacký administration were referred to as "pro-administration" and would eventually form the Republic Union Party, while those in opposition largely joined the emerging National Democratic Party.

Greatly concerned about the very real capacity of political parties to destroy the fragile unity holding the nation together, Palacký remained unaffiliated with any political faction or party in his first term in office, however he was forced to join the Republican Unionists in his remaining two terms as tensions rose over unity in and out of the party. He was, and remains, the only Morrawian president never to be affiliated with a political party, at least for one term. Since Palacký, every Morrawian president has been affiliated with a political party at the time of assuming office.

The number of presidents per political party by their affiliation at the time they were first sworn into office (chronologically) are:

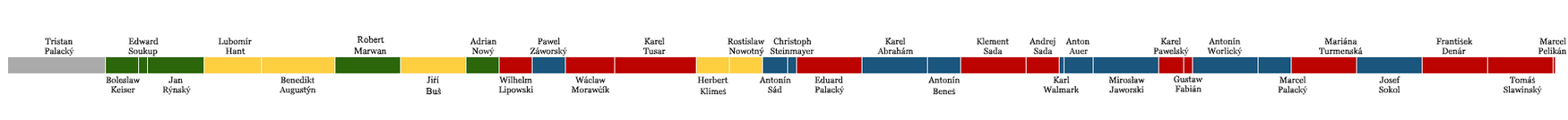

Timeline of presidents

The following timeline depicts the progression of presidents and their political affiliation at the time of assuming office: