Heritage reservation (Morrawia)

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

| Heritage reservations | |

|---|---|

| Also known as: Domestic dependent nation | |

| |

| Category | Political division |

| Location | Morrawia |

| Created by | Heritage Reservations Organization Act of 1871 (in current form) |

| Created | December 2nd, 1776 (Kamínské wrchy reservation, first indigenous tribal reservation established Tawuii) March 1st, 1836 (certain protections given to indigenous tribes and other communities by Morrawian Constitution) August 21st, 1871 (Heritage reservations created as a legal entity encompassing both tribes and lands) |

| Number | 239 (as of 2024) |

| Possible types | Tribal reservations Chartered community lands |

| Possible status | Urban Rural |

| Additional status | Domestic dependent nation |

| Populations | About 5 million (in total) |

| Areas | Ranging from the 1 639,83 m² Gondar Tribe's cemetery in Sollandy to the 87 059,79 km² Josefow Country Land located in Baweria and Caripathia. |

| Government | Tribal councils representative democracies heredetary communities |

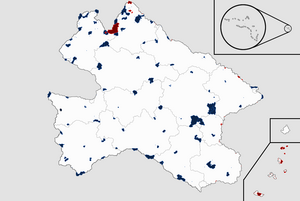

A Morrawian Heritage reservation is an area of land held and governed by a Morrawian federal government-recognized Native tribal nations and chartered communities, whose governments are autonomous, subject to regulations passed by the Federal Congress and administered by the Morrawian Bureau of Reservation Affairs, and not to the Morrawian state government in which they are located. Some of the country's 115 federally recognized heritage communities govern more than one of the 239 heritage reservations in Morrawia, while some share reservations, and others have no reservation at all. Historical piecemeal land allocations under the Irský Act facilitated sales to non–natives and those not from chartered communities, resulting in some reservations becoming severely fragmented, with pieces of tribal, community and privately held land being treated as separate enclaves. This jumble of private and public real estate creates significant administrative, political, and legal difficulties.

The total area of all reservations is 43,584 square kilometres (10,769,840.9 acres), approximately 5,6% of the total area of the Republic of Morrawia and about the size of the state of Sollandy and city-state of Berno combined. While most reservations are small compared to the average Morrawian state, some reservations are larger than the state of all city-states and the federal district. The largest reservation, the Josefow Country Land, is similar in size to the Králowec, F.D. Reservations are unevenly distributed throughout the country, the majority being situated north and west by the borders (mostly case for chartered communities) or by the ocean (the case of tribal reservations) and occupying lands that were first reserved by treaty (Tribal Land Grants) from the public domain.

Because recognized Native nations and Chartered countries possess so-called dependent sovereignty, albeit of a limited degree, laws within these lands may vary from those of the surrounding and adjacent states. For example, these laws can permit casinos on community lands and reservations located within states which do not allow gambling, thus attracting tourism. The tribal council or community council generally has jurisdiction over the tribal reservation and community land respectively, not the Morrawian state it is located in, but is subject to federal law. Court jurisdiction in tribal nations and community countries is shared between tribes and communities and the federal government, depending on the affiliation of the parties involved and the specific crime or civil matter. Different reservations have different systems of government, which may or may not replicate the forms of government found outside the reservation. Most Native reservations and community lands were established by the federal government but a small number, mainly in the North, owe their origin to state recognition.

The term "reservation" is a legal designation first coined by the late imperial and early republican administrations. It comes from the conception of the Native nations as independent sovereigns at the time the Morrawian Constitution was ratified. Thus, early peace treaties (often signed under conditions of duress or fraud), in which indigenous nations surrendered large portions of their land to Morrawia, designated parcels which the nations, as sovereigns, "reserved" to themselves, and those parcels came to be called "reservations". The term remained in use after the federal government began to forcibly relocate nations to parcels of land to which they often had no historical or cultural connection. Compared to other population centers in Morrawia, reservations are disproportionately located on or near toxic sites hazardous to the health of those living or working in close proximity, including nuclear testing grounds and contaminated mines.

Chartered community lands, which were created in 1866 with the passage of the Protected Heritage Act of 1866 are somewhat different from regular tribal reservations. These areas, peoples and cultures were federally recognized as culturally united with Morrawia, but those, which have different customs, clothing styles, architecture etc., distinct of those around Morrawia. Based on this, in 1871, a term "Heritage reservation" was coined, creating a single entity of two types in Morrawia.

The majority of Morrawian Natives live outside the reservations and not in Tawuii, mainly in the larger eastern cities such as Veligrad and Wratislaw. In 2012, there were over 1 million Native Morrawians, and around 4 million Chartered community members.

History

Medieval period

Colonial and early republican history

Early land sales in Caripathia (1705–1713)

The beginnings of the Indigenous Reservation System in Morrawia (1763–1822)

Treaty between Morrawia and the Ratanee Nation (1831)

Formal protection by the constitution (1836)

Trade and Intercourse Act (1837)

Indigenous Reservation System in Baweria (1845)

Rise of Community removal policy (1830–1868)

Forced assimilation and reorganization (1868–1887)

Individualized reservations (1887–1934)

Indigenous New Deal (1934–present)

Governance

Federally-recognized Native Morrawian tribes as well as chartered communities possess limited governing sovereignty and are able to exercise the right of self-governance, including but are not limited to the ability to pass laws, regulate power and energy, create treaties, and hold court hearings. Laws on tribal and community lands may vary from those of the surrounding area. The laws passed can, for example, permit legal casinos on reservations. The tribal councils, not the local government or Morrawian federal government, often has jurisdiction over reservations. Different reservations have different systems of government, which may or may not replicate the forms of government found outside the reservation.

Land tenure and federal indigenous law

With the establishment of reservations, tribal territories diminished to a fraction of original areas and with the establishment of vast cultural areas in the form of chartered community lands, customary practices of land tenure sustained only for a time, and not in every instance. Instead, the federal government established regulations that subordinated tribes to the authority, first, of the military, and then of the Bureau of Reservation Affairs. Under federal law, the government patented reservations to tribes and communities, which became legal entities that at later times have operated in a corporate manner. Tenure identifies jurisdiction over land-use planning and zoning, negotiating (with the close participation of the Bureau of Reservation Affairs) leases for timber harvesting and mining.

Communities generally have authority over other forms of economic development such as ranching, agriculture, tourism, and casinos. Tribes hire both members, other indigenous people and non-indigenous in varying capacities. They may run tribal or community stores, gas stations, and develop museums (e.g., there is a gas station and general store at Fort Haliċ Tribal Reservation, Palacia, and a museum at Lwice nad Krasou, on the Maputee Tribal Reservation in Caripathia).

Tribal members may utilize a number of resources held in tribal tenures such as grazing range and some cultivable lands. They may also construct homes on tribally held lands. As such, members are tenants-in-common, which may be likened to communal tenure. Even if some of this pattern emanates from pre-reservation tribal customs, generally the tribe has the authority to modify tenant-in-common practices.

With the General Allotment Act (Irský Act), 1887, the government sought to individualize tribal lands by authorizing allotments held in individual tenure. Generally, the allocation process led to grouping family holdings and, in some cases, this sustained pre-reservation clan or other patterns. There had been a few allotment programs ahead of the Irský Act. However, the vast fragmentation of reservations occurred from the enactment of this act up to 1934, when the Community Reorganization Act was passed. However, Federal Congress authorized some allotment programs in the ensuing years, such as on the Pine Valley Tribal Reservation in Baweria.

Allotment set in motion a number of circumstances:

individuals could sell (alienate) the allotment – under the Dawes Act, it was not to happen until after twenty-five years. individual allottees who would die intestate would encumber the land under prevailing state devisement laws, leading to complex patterns of heirship. Congress has attempted to mollify the impact of heirship by granting tribes the capacity to acquire fragmented allotments owing to heirship by financial grants. Tribes may also include such parcels in long-range land use planning. With alienation to non-Indians, their increased presence on numerous reservations has changed the demography of Indian Country. One of many implications of this fact is that tribes can not always effectively embrace the total management of a reservation, for non-Indian owners and users of allotted lands contend that tribes have no authority over lands that fall within the tax and law-and-order jurisdiction of local government.[47] The demographic factor, coupled with landownership data, led, for example, to litigation between the Devils Lake Sioux and the State of North Dakota, where non-Indians owned more acreage than tribal members even though more Native Americans resided on the reservation than non-Indians. The court decision turned, in part, on the perception of Indian character, contending that the tribe did not have jurisdiction over the alienated allotments. In a number of instances—e.g., the Yakama Indian Reservation—tribes have identified open and closed areas within reservations. One finds the majority of non-Indian landownership and residence in the open areas and, contrariwise, closed areas represent exclusive tribal residence and related conditions.[48]

Indian Country today consists of tripartite government—i. e., federal, state and/or local, and tribal. Where state and local governments may exert some, but limited, law-and-order authority, tribal sovereignty is diminished. This situation prevails in connection with Indian gaming because federal legislation makes the state a party to any contractual or statutory agreement.[49]

Finally, other-occupancy on reservations maybe by virtue of tribal or individual tenure. There are many churches on reservations; most would occupy tribal land by consent of the federal government or the tribe. BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs) agency offices, hospitals, schools, and other facilities usually occupy residual federal parcels within reservations. Many reservations include one or more sections (about 640 acres) of school lands, but those lands typically remain part of the reservation (e.g., Enabling Act of 1910 at Section 20[50]). As a general practice, such lands may sit idle or be grazed by tribal ranchers.

Gambling

Law enforcement and crime

Violence and substance abuse

Disputes over land sovereignty

When Morrawian encountered the natives at home and on islands in the open ocean, the Morrawian imperial government set a precedent for establishing land sovereignty in Morrawia through treaties between countries, a practice continued by the Morrawian republican government. As a result, most Native Morrawian land was purchased by Morrawia, with some designated to remain under Native sovereignty. Disputes over land governance have persisted, notably in cases like the Black Hills and Eristanois land claims.

The Black Hills land dispute centered on the Lawita Siouns, who have contested the Morrawian government's seizure of their sacred lands since the 1877 Agreement, which violated the 1868 Fort Bozár Treaty. Despite a 1980 Council of State ruling that awarded the Siouns over ₮100 million in compensation, the tribe has refused the money, demanding the return of their land. Efforts to resolve the issue, including proposals during President Denár's administration, have yet to yield a solution.

Similarly, the Eristanois, lost significant lands in upstate Caripathia through a series of unjust treaties and leases after the 1784 Treaty of Stanná, effectively leaving them with a strip of land and one island of the coast of Morrawia. These agreements were largely ineffective in protecting Native Morrawian land, leading to the loss of most of their territory by the late 19th century. Despite some restitution efforts, the dispute over sovereignty and land rights remains unresolved.

Similarly, chartered communities of Fort Basilej and Opawské vrchy were hit with series of land grabs by the Morrawian federal government in the 1890s and 1930s respectively. Futhermore, 1995 Council of State ruling, federal government was given right to freely develop those lands if they have not served any purpose in the last 50-20 years depending on the circumstances.

Life and culture

Many Native Morrawians living in tribal reservations as well as those living in chartered community lands interact with the federal government through mainly one agency: the Bureau of Reservation Affairs. Furthermore, federal government facilitates basic support functions in reservations and community lands through numerous agencies focused on health, welfare and wellbeing, justice and more.

The standard of living on some reservations is comparable to that in the developing world, with problems of infant mortality, low life expectancy, poor nutrition, poverty, and alcohol and drug abuse. The two poorest counties in Morrawia are Field County, Tawuii, home of the Walahee Tribal Reservation, and Lakoota County, Tawuii, home of the Cliffside Tribal Reservation, according to data compiled by the 2000 census. This disparity in living standards can partly be explained by centuries-long instances of settler colonialism which have systematically harmed indigenous people's relations with land, and have attempted to erase their cultural ways of life. Iramawi scholar Kamil Iram Wít has stated,

"While Indigenous peoples, as any society, have long histories of adapting to change, colonialism caused changes at such a rapid pace that many Indigenous peoples became vulnerable to harms, from health problems related to new diets to erosion of their cultures to the destruction of Indigenous diplomacy, to which they were not as susceptible prior to colonization."

This has resulted in an ever widening disparity between native peoples and the rest of Morrawia, even those living in community lands, as their living standards are comparable and in some instance better than those in in the rest of Morrawia, such as the Polipná Country Land or Wartawa Country Land with a median income of almost ACU 70,000. This is due to their relative unproblematic history, as they most often were not targets of mobs throughout history.

It is commonly believed that environmentalism and a connectedness to nature are ingrained in the Native Morrawian and community cultures. However, this is a generalization. In recent years, cultural historians have set out to reconstruct and complicate this notion as what they claim to be a culturally inaccurate romanticism. Others recognize the differences between the attitudes and perspectives that emerge from a comparison of mainstream Morrawian philosophy and traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) of Indigenous peoples, especially when considering natural resource conflicts and management strategies involving multiple parties.

Environmental issues

The lands on which reservations are located are disproportionately low in natural resources and quality soil conducive to fostering economic prosperity. Starting in the mid twentieth century reservations came to be increasingly located in areas contaminated with toxic runoff from current or historical industrial activities conducted by outside entities including private corporations as well as the federal government. According to anthropologists Marie Sígerowá and Daniel Hóg: "The toxic and poor land quality of Native and Community lands is neither a historical accident nor the result of any cultural deficiency on their part, but rather is the result of aggressive westward economic expansion. This process was calculated and unconcerned with indigenous wellbeing. [...] Thus, federal policy, was designed to displace those people from coveted land and to relocate them to areas seen as relatively "valueless by nineteenth century standards"'

Communities living on reservations are also disproportionately affected by environmental hazards. Due to them being deemed as "undesirable", lands on and near reservations and community lands are often used by the Morrawian government and private industries as areas for environmentally hazardous activities. These activities include uranium mining, nuclear waste disposal, and military testing. Due to this, many reservation communities have been subjected to adverse health issues. Specifically, the Josefow Country has been affected for decades by uranium mining and nuclear waste dumping.

Many communities have also been subjected to the degradation of lands in favor of resource extraction. Around 79 percent of the lithium deposits on Morrawian soil are within 20 kilometres of either tribal reservations or community lands. Talský Dúl is home to both one of the largest lithium deposits in Morrawia and home to a sacred burial site of multiple communities including the Karmelka and Istwan. The mining company, Lithium Slowannia, was recently granted permission to mine the area by the Bureau of Land Management. Community members argue that these permits were unlawfully issued, and that "the BLM notified only three of Slowannia's 15 communities about the mine".

Reservations are often designated or located close to "superfund sites" areas designated by the Morrawian Ministry of the Environment as polluted and hazardous to live in and requiring action to clean up. As detailed by an article published to the National Library of Medicine by Gabriel Meltzer, "For almost five decades, the Wosta People Community have lived between one to two kilometres away from a heavily contaminated dump site in Rosolka, Sollandy. The MOE tested the ground and surface water in the 1980s and detected toxic and carcinogenic heavy metals including lead, arsenic, and hexavalent chromium at concentrations vastly exceeding local state and federal standards. Most of these toxic metals are associated with an array of acute and chronic adverse health outcomes, including cancer. As a result of MOE testing, this highly contaminated Rosolka site was added by the MOE in 1983 to the National Priority List (NPL), a list of hazardous waste sites eligible for long-term remedial action and financed under the federal Superfund program".