Montecara

Montecaran Republic Repùblica montecarà | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Virtus nostrum tutamen Virtue is our safeguard (Solarian) | |

| Anthem: Inno dei Populi "Hymn of the People" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Montecara 28°30′N 6°40′E |

| Official languages | Montecaran |

| Demonym(s) | Montecaran |

| Government | Directorial republic Direct democracy |

• Head of Government | Colegio |

| Legislature | Senate and Popular Assembly |

| Establishment | |

• City founded | 542 BCE |

• Restoration of independence | 28 April 1935 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,145.43 km2 (442.25 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 19.04 |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | 1,801,328 |

• Density | 2,091.61/km2 (5,417.2/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $153,136 million |

• Per capita | $85,013 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $158,955 million |

• Per capita | $88,243 |

| Gini (2019) | high |

| HDI (2019) | very high |

| Currency | Montecaran libra (MCL) |

| Time zone | UTC |

| Date format | yyyy-mm-dd (official) dd-mm-yyyy (common use) |

| Driving side | right |

| ISO 3166 code | MC |

| Internet TLD | .mc |

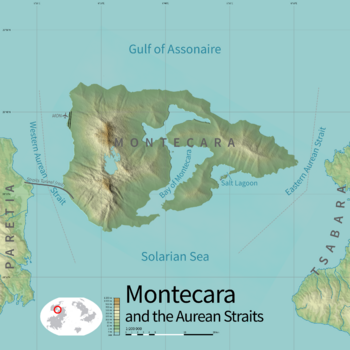

Montecara (Montecaran: [ˌmonteˈkärä]), officially the Montecaran Republic (Montecaran: Repùblica montecarà), is a city-state of approximately 1.7 million people located on a 689 square kilometer main island and scattered islets located in the middle of the Aurean Straits between Euclea and Coius. It lies at the meeting point of the Solarian Sea and Gulf of Assonaire at the narrowest point of the world's busiest sea trade route. Montecara is noted for its unique government and deep-rooted culture stretching back to Solarian times, and is one of the smallest and richest nations in the world.

Montecara is governed under a collegial system which relies heavily on direct democracy, setting it apart from almost all modern states. Every citizen aged 20 and older is a member of the legislature, either in the Popular Assembly (Senblèa Popolà), the lower house, or the Senate (Senàt), the appointed upper house. The Colegio, a seven-member body elected by the Senate, is the collective head of government and makes executive decisions by consensus.

The Montecaran economy is highly developed and specialized. The state is a major financial center and offshore banking hub and maintains an open ship registry, with the result that a large percentage of the world's merchant ships are Montecaran-flagged. The state controls a large number of corporations under the umbrella of Montepietà, the sovereign wealth fund, which feeds dividends back to the public treasury. Montecara's tax policy is famously straightforward and simple, as it has no income, capital gains, estate, or dividends taxes, which makes it an attractive location for multinational firms to incorporate but has also led critics to label it a tax haven. The currency, the Montecaran libra, is pegged to the Euclo.

Because of its considerable age and natural limits to growth as an island state with rugged terrain, Montecara boasts a dense and walkable urban environment surrounded by well-preserved areas of natural beauty. These factors have contributed to making Montecara one of the world's premier tourist destinations, with an estimated 7.1 million visitor arrivals in 2017.

Etymology

Little is known about what early human settlers in Montecara called the island. The first written record that provides a definitive name is a tablet discovered near Bayadha in northern Tsabara dated to approximately 1000 BCE which refers to 𐤇𐤉𐤌 (ḥym), possibly a compound formed from roots meaning "sea" and "enclosure." Ancient Piraeans referred to the island as Πύλαι (Púlai), likely from a root meaning "gateway." The current name comes from the Solarian roots for "mountain" and "face," evidently from the striking rock formation that dominates Montecara's skyline.

History

| Part of a series on the History of Montecara |

| Historic rulers of Montecara |

|---|

|

| Piraean polis |

| 542 BCE – 415 BCE |

|

|

| 415 BCE – 259 BCE |

|

|

| 259 BCE – 15 CE |

|

|

| 15 CE – 426 CE |

|

(Ducal Republic) |

| 426 – 1792 |

|

|

| 1792 – 1810 |

|

|

| 1810 – 1935 |

|

|

| 1935 – 1944 |

|

|

| 1944 – 1946 |

|

|

| 1946 – present |

Prehistory and antiquity

A land bridge connecting Euclea and Coius formed approximately 5.5 million years ago, becoming a much broader connection between the two continents during the last ice age before reverting to a narrow isthmus amid rising sea levels by 17,000 BCE. Because of its strategic location, the Montecaran land bridge became the primary migration route for early humans leaving Coius for Euclea.

By the end of the ice age in approximately 9000 BCE, Montecara had assumed its present island form. With the dissolution of the land bridge, the island became a semi-permanent place of refuge for tribes which sustained themselves by fishing in its protected bay along trips up and down the Euclean and Coian coasts in a form of marine nomadism.

Piraean sailors reached Montecara in the early sixth century BCE and recognized its usefulness as a natural harbor and place of abundant fish. A permanent colony soon followed, with the exact year of Montecara's foundation as a city traditionally given as 542 BCE.

Classical period

Montecara was conquered by forces of the Solarian Republic in 259 BCE. The city would remain part of the Republic for nearly seven centuries, with Solarian civilization leaving a profound mark on Montecaran government, language, art, and culture that endures to this day.

The Solarians wasted little time in recognizing Montecara's economic value. The expansive natural harbor offered protection for seafarers and made it easy to harvest abundant stocks of shellfish. Perhaps even more importantly, the Lacùna da sel (Salt Lagoon) was a readily accessible source of sea salt thanks to its vast, shallow expanse and Montecara's warm climate, which allowed for easy and inexpensive solar evaporation. Early trade was organized around fishing, salting the catch, and then exporting it to other parts of the Republic. Archaeological records indicate that the salted fish trade was being exploited on an industrial scale by the middle of the first century BCE.

The city remained part of the Solarian world through the fall of the Republic and birth of the Empire in 15 CE. Central authority began to crumble in the early fourth century CE, and after a series of civil wars exhausted the state's resources, the last Imperial troops withdrew from Montecara in 426.

Middle ages

By the early fifth century, Montecara had been left largely to fend for itself. The population dwindled as Solarian civilization receded, drying up trade and leaving infrastructure to crumble. Montecara was once again a minor fishing settlement and trading post that fought off occasional seaborne raids, only surviving thanks to its sheltered location and Solarian-built defenses. It existed amid a patchwork of other city-states, feudal holdings, and petty kingdoms that had been left behind as civilization faded.

It differed from them, however, in its advantageous geography and stable governance. Because the city's leading families recognized their need to band together in a world of hostile pirates and barbarians but were also determined not to let any one family grow too powerful, they maintained the city-state's Solarian civic republicanism. Emulating the government of the old Republic, they formed a Senate of prominent family chiefs who chose a leader from among themselves. This official was called the Doxe (from Solarian dux, "leader"), and he served for life as primus inter pares. This in turn strengthened the state's identity and gave its rulers a sense that they had a stake in the common good, and that they could not simply rule for their own profit and power.

From the sixth through the tenth centuries, Montecara grew considerably in might as its fleet grew from fishing boats to powerful galleys. As the fleet reached far-flung ports, mariners set up colonies and trading posts around the Solarian Sea that reached deep into the hinterland. Citizen-soldiers were augmented by large numbers of mercenaries recruited from abroad. This colonial thalassocracy became known as the Stado Ultramarìn (Ultramarine State). The city-state's newfound naval power enabled it to negotiate treaties with other states that granted it trade concessions in exchange for naval protection. Montecara's stores of salt and preserved fish made it an important trade destination, and the salt tax (gabèla) became a major source of state income. Merchant fleets were supported by an increasingly elaborate financial system that included some of the first precursors to joint-stock corporations by the early 1300s.

This period also laid the foundation of Montecara's formidable banking sector as the process of financing trade became formalized. Lending money at interest was considered unholy, so Montecaran merchants skirted around the practice in various ways, for instance by lending in one currency or precious metal and requiring payment in another, higher-valued alternative. As these arrangements became common, the taboo against moneylending faded, and the forerunners of modern banks were founded in the twelfth century. Montecarans also laid the groundwork for the modern system of government bonds, in large part thanks to the fact that, as a republic, creditors did not need to fear that a truculent king or prince might refuse to pay back the loans that had been issued to him personally. Montecaran credit was the responsibility of the state as a whole, which greatly increased lenders' confidence that they would be paid back and thus allowed Montecara to borrow at far lower rates than would have been offered to monarchs. This cheap credit was reinvested in infrastructure, naval power, and early industry, providing Montecara with a key advantage against other polities of the era.

The elite used their wealth to fund great achievements in art and architecture, including the Basìlica di San Stefàn (completed circa 1290). Wealthy merchant families patronized authors, playwrights, composers, acting troupes, and musicians, even outbidding each other to secure the most fashionable artists for their households. Fashion, too, became a focus of elite life, with the most expensive outfits fetching sums large enough to buy an apartment.

This period of growth and prosperity also had a dark side. The Montecaran economy became reliant on an exploitative trade system based on plantation-grown coffee, spices, cocoa, sugar, and tobacco, and most notoriously, the Coian slaves who produced these lucrative crops. Montecara became a hub of the slave trade by the mid-16th century. Captives from Coius and western Euclea were brought in fetters to Montecara to be sold, often being reexported to continental Euclea. The most common use for slaves sold in Montecaran markets was as agricultural labor; women, considered more useful for domestic purposes, fetched a premium, and eunuchs were some of the most valuable slaves of all. This meant that a lively trade in these castrati arose, and slave-trading houses often employed a professional castratòr to neuter prepubescent boys. The long tradition of castrati in Montecaran music is one of the curious legacies of this period. The Montecaran slave trade was finally abolished only in 1820, though slavery was banned on Montecaran soil in 1758 due to fear of slave rebellions.

Early modern period

Montecara's navy, which boasted over 3,000 vessels at its height, was made increasingly obsolete during the seventeenth century by the widespread adoption of large sail-powered vessels in place of sail-and-oar ships. Montecaran commanders, who had always favored large crews of oarsmen to power their warships, were hampered by intransigence and soon found their military edge dulling. The republic gradually lost many of its overseas territories to hostile neighbors throughout the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

Modern period

Montecara fell under the domination of the Gaullican Empire in 1810 and would remain so for the next 125 years. The Gaullicans had long sought control of the Aurean Straits for their vital strategic importance and ran Montecara largely as a fortress and naval base. This had the salutary effect of keeping the desire for cultural domination to a minimum; although Gaullican became the language of government and higher education, there was no attempt to thoroughly Gaullify Montecaran society. Gaullican rule was also not without local investment. The occupying authority improved the Port of Montecara and built the island's first rail system. Montecarans were recruited into the Gaullican Navy, where their expertise at seafaring was valued.

Montecara was an integral part of the Gaullican Empire and so was brought under the functionalist rule of the Parti Populaire on 7 October 1920 with the exile of King Albert III. Functionalism, born in Gaullica as a reactionary movement led by certain elements of the military, took root among the petite bourgeoisie of merchants and professionals that had grown exponentially under nineteenth-century capitalism but which still found themselves with little to no structural power in a political system that was still organized along feudal lines. This sudden assertion of class consciousness created a rift between them and the haute bourgeoisie of landowners and old aristocratic families they had previously identified with in opposition to common workers, radically transforming the political and class structure of Montecaran society in the space of less than a decade.

Socially, Gaullican functionalism intensified the regressive and anti-modern tendencies of the old Empire. The government imposed strict Catholic social and religious mores; it closed brothels and attempted to "rehabilitate" sex workers by confining them in workhouses and convents, which forced the sex trade underground and made it far more dangerous for those who still plied it. The regime was stridently opposed to homosexuality and shuttered meeting places, especially bars and clubs, that were seen to have an LGBT clientele. Inter-community relations between Solarian Montecarans and Atudites, many of whom had roots in Montecara that were centuries-deep, deteriorated as the government emphasized an ethno-racial hierarchy and attempted to forcibly assimilate minorities by encouraging the intermarriage of ethnic Solarian men and minority women. The regime lasted fifteen years until the defeat of the Gaullican Empire in the Great War. The reassembled Senate proclaimed Montecaran independence on 28 April 1935, restoring the sovereignty that had been lost since 1810.

Although the vast majority of Montecarans welcomed independence, the Gaullican occupation and functionalist rule had left profound divisions in society. The haute bourgeoisie moved immediately to reassert itself. Landowners, perhaps ironically, become some of the major supporters of left-wing reforms as they wished to both break the power of the upstart middle classes and elevate the economic status of the proletariat, which would allow them to increase rents. Although the church had an overbearing and increasingly resented position in society under the Gaullicans, it had at least provided basic social services such as elementary and secondary education and hospitals, not the least to quiet calls for a modern social welfare state. These services were, however, widely seen as clearly inadequate for a modern country by the standards of the mid-1930s. Attacked by both the radicalizing proletariat for their parasitic nature and the upper classes for their treacherous support of functionalism, the church found itself in a position of rapidly diminishing influence. Newly independent labor unions stepped into the gap to provide social services for their members, organizing schools, clinics, and even cash support for struggling workers. For the remainder of the 1930s and into the first years of the 1940s, Montecaran society would remain in a state of slow-burning civil discord. The conservative, pro-church, and occasionally pro-Gaullican faction of functionalist holdouts was pitted against a broadly liberal coalition of modernizing anti-clericalists, civic nationalists, socialists, and trade unionists.

All the while, a threat was growing across the sea in the Solarian homeland of Etruria. The Etrurian Revolutionary Republic, formed in 1938, had taken up the mantle of functionalism and married it with an ambition of reunifying the ancient Solarian Empire under the rule of Supreme Leader Ettore Caviglia. The assimilation of Montecara was to be a key part of this plan, both for the city-state's strategic location and for its idealized status as a bastion of Solarian civilization. Agents of the Etrurian state made inroads into the disgruntled elements of Montecaran society that were already sympathetic to the functionalist cause, laying the groundwork for a fifth column that could be called up in the event of an invasion. Once the Solarian War was put into motion, the invasion of Montecara was a foregone conclusion. Using the pretext of bringing peace to civil strife and protecting their Solarian brothers and sisters, the Etrurian armed forces landed in Montecara early on the morning of 4 March 1944. They encountered no organized resistance; elements of the tiny and underfunded Montecaran military deserted or, in many cases, welcomed the Etrurians. Although some sporadic street violence driven largely by socialists marked the early days of the occupation, the Etrurian invasion had been largely unopposed and bloodless. The Etrurians soon organized a referendum, later proved to be fraudulent, that legitimized the occupation and formally made Montecara part of the Etrurian state. Montecara would remain under occupation for nearly two years.

Although the invasion had been rather peaceful, the liberation was far from it. The Community of Nations, fresh from the liberation of Emessa and southern Etruria, called on the Etrurian garrison in Montecara to surrender and declare an open city but was rebuffed. In response, CN forces attacked and liberated Montecara over the course of 8–10 February 1946. The defeat and expulsion of the Etrurians represented the final defeat of functionalism as a legitimate political force in Montecara. The CN organized a provisional government for Montecara that was in power from February 1946 to 8 June 1948, during which time an extensive process of "de-functionalization" was undertaken. The Montecaran constitution was revised to strengthen democratic institutions and create a military based on universal service that would deter future invasions. The Aurean Straits were declared to be an international waterway and the system of tolls that Montecarans had for centuries charged foreign ships to use them were finally abolished. Lastly, the CN made an ongoing commitment to protect Montecaran sovereignty with the understanding that the international status of the Straits would not be challenged.

Geography

Montecara consists of 689 square kilometers of land in the Aurean Straits. Almost all of Montecara's land consists of a single island, officially called the Island of Montecara but referred to locally as ia Isolòna ("the Big Island"), which measures approximately 41 km across its extreme points. It is nearly cut in half by an immense natural harbor, the Bay of Montecara, which has sheltered vessels and provided food to local inhabitants for millennia. The bay is considered part of Montecara's integral territorial waters, as is the Lacùna da sel ("Salt Lagoon"), a natural area of shallow water that is so named because it has been exploited as a ready source of sea salt since prehistoric times. Other islands adjacent to the main island include Lazarèt, a barrier island at the mouth of the Lacùna da sel, and Oçì, an islet in the Bay of Montecara that has hosted a small monastic community for over a thousand years.

The islands and surrounding region have a karst topography of rugged cliffs and cavernous rock formations. This exposed stone has long provided locals with a readily accessible building material but has limited the island's arable land, one of the main factors motivating Montecara's long reliance on trade and emphasis on fishing. Despite its small size, Montecara features dramatic changes in elevation. Its highest point is the peak of ia Corònela at 1,231 meters above sea level, and parts of the island have cliffs of 30 meters or more that drop off into the sea. Geological hazards include sinkholes and earthquakes.

Climate

Montecara is situated 28 degrees north of the equator at the point where two continents and two seas touch. This geography creates wind and sea currents that moderate the often hot climate at this latitude. Montecara has a subtropical semi-arid climate (Köppen BSh), with quite warm and dry summers and mild and relatively wet winter.

| Climate data for Montecara (1980–2010), Extremes (1920–2016) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.4 (83.1) |

31.2 (88.2) |

35.4 (95.7) |

35.2 (95.4) |

36.4 (97.5) |

37.1 (98.8) |

42.6 (108.7) |

40.4 (104.7) |

39.3 (102.7) |

38.1 (100.6) |

34.0 (93.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

42.6 (108.7) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 22.6 (72.7) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.9 (76.8) |

25.0 (77.0) |

26.3 (79.3) |

28.5 (83.3) |

31.1 (88.0) |

31.4 (88.5) |

29.7 (85.5) |

28.0 (82.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.1 (75.4) |

31.4 (88.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 21.0 (69.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

26.2 (79.2) |

28.7 (83.7) |

29.0 (84.2) |

28.1 (82.6) |

26.3 (79.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

22.1 (71.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 18.2 (64.8) |

18.3 (64.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

21.0 (69.8) |

22.9 (73.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.9 (76.8) |

23.4 (74.1) |

21.3 (70.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.5 (70.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 15.4 (59.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

15.9 (60.6) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.8 (64.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.7 (71.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

18.4 (65.1) |

16.6 (61.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 14.2 (57.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

19.8 (67.6) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

18.9 (66.0) |

16.3 (61.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

14.0 (57.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 9.4 (48.9) |

8.1 (46.6) |

9.5 (49.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

12.0 (53.6) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.0 (62.6) |

16.8 (62.2) |

14.6 (58.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

10.0 (50.0) |

8.1 (46.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 31.5 (1.24) |

35.4 (1.39) |

37.8 (1.49) |

11.6 (0.46) |

3.6 (0.14) |

0.9 (0.04) |

0.1 (0.00) |

2.0 (0.08) |

6.8 (0.27) |

18.7 (0.74) |

34.1 (1.34) |

43.2 (1.70) |

225.7 (8.89) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4.2 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 3.1 | 4.7 | 5.4 | 29.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (daily average) | 64 | 63 | 62 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 58 | 61 | 65 | 65 | 64 | 67 | 63 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 178 | 186 | 221 | 237 | 282 | 306 | 337 | 319 | 253 | 222 | 178 | 168 | 2,913 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 52 | 60 | 59 | 61 | 65 | 73 | 78 | 79 | 70 | 65 | 54 | 54 | 64 |

| Source: Secretariat of Planning and the Environment | |||||||||||||

Wildlife

Montecara is home to a diverse array of native plants and animals, including a wide variety of marine life, migratory birds, reptiles, and amphibians. The native plant biome is dominated by hardy shrubs and grasses, collectively referred to as màçia, which tolerate hot and dry seasons well. The country is on a major flyway for migratory birds, and native species include waterfowl such as cormorants, herons, pelicans, ducks, and gannets.

Politics

Montecara is a liberal democratic republic with a written but uncodified constitution. Politics in Montecara are strongly influenced by its direct-democratic system, wherein every adult citizen is a member of either the Popular Assembly or Senate and is accordingly entitled to participate in the writing and approval of laws. Unlike in most states, politics (and to a large extent, society in general) are built on a model that strongly favors consensus decision-making, collaboration, and cooperation.

Constitution

Montecara has a written constitution, the oldest parts of which date to 1117. Rather than being codified into a single document, it is organized into two books plus the Instrument of Ratification, which was added after a major revision in 1936.

Citizenship

Citizenship is the basis of the Montecaran government, as citizens make up the legislature and govern largely by direct democracy. Montecara is a jus sanguinis state, in which birthright citizenship is only available to people with at least one Montecaran citizen parent at the time of birth. The only other way to acquire Montecaran citizenship is to have it granted by law, which is quite rare, with only 10 to 50 Montecaran citizens created through naturalization each year on average.

The Montecaran government does not recognize multiple citizenship; Montecaran citizens who acquire the citizenship of another country or who become members of a noble or royal house are considered to have renounced their citizenship. Similarly, naturalized citizens are considered to be solely citizens of Montecara. Montecarans can also lose their citizenship if they serve another country in a civil office or military capacity or formally renounce their citizenship before a Montecaran consul.

Legislature

(The Senate and the People of Montecara decree)

—Enacting formula for Montecaran laws

Montecara's political system is designed to distribute power as broadly as possible in order to maintain a powerful citizenry. Accordingly, it is governed as a direct democracy and directorial republic, with elements of sortition added to prevent corruption. Citizens of legal age who are not Senators are all members of the Popular Assembly, the lower house of the legislature, which must approve all laws and treaties before they come into effect. Voting was once done at mass meetings held in the fields outside the city, but since 1988 has been done exclusively by postal ballot for one week each in March and September.

The Senate (Senàt) is the upper house of the legislature, and is intended to provide experienced oversight to government functions. It is the court of last resort for administrative law and is empowered to conduct investigations. The Colegio, a seven-member body, functions as the collective head of government and cabinet and is responsible for proposing legislation and setting policy.

Judiciary

Montecara is a civil law jurisdiction, basing its judiciary on Solarian law. Trials are conducted using the inquisitorial system. Judges are appointed by law, and courts are organized into a three-tiered hierarchy with separate streams for civil, criminal, and administrative cases. In some cases, lay judges contribute to resolving the case. Criminal cases are prosecuted by a proctor (protòre), a state official. The General Proctor (Protòre-xenèr) is the state's senior prosecutor and is called on to represent the interests of the state itself in matters of national or international importance. Because Montecara's judiciary is governed by civil law, judges are not empowered to make or invalidate laws; nonetheless, the doctrine of jurisprudence constante is influential, and courts will often cite similar cases where the same judgement was reached when making their decisions.

Criminal offenses are categorized into three tiers: the contravènxon, a minor offense which carries a maximum penalty of a Ł5,000 fine and no detention; the delito, which may be punished with a maximum fine of Ł25,000 and detention for up to twelve months; and the crìma, which is subject to unlimited fines and imprisonment. In criminal matters, the unanimous agreement of the professional and lay judges is required for conviction. There is no insanity defense; defendants judged guilty but insane are committed to specialized psychiatric care within the penal system. Administrative offenses, including petty traffic violations, are punishable only with fines or other remedies such as removal in the case of immigration violations, not a custodial sentence.

Montecara has a moderate-to-low incarceration rate by world standards of 75 per 100,000 people as of 2018. This works out to a prison population of approximately 1,300 inmates on average for 2018. These inmates are held in one of three principal locations: the main, mixed-security prison at Molàro, the special unit for medical and psychiatric prisoners at the Ospedàl Marìn, or the military prison at Castèl Gerò. By far the largest and most populous of these is Molàro, which holds approximately 1,000 prisoners. There are six to nine murders in an average year; the homicide rate as of 2017 is .51 per 100,000 people.

Local government

Montecara is traditionally divided into the city (çìta) and countryside (canpo). The dividing line between the two is known as the pomero in a tradition that goes back to the Solarian Republic. While the so-called countryside was once almost entirely rural and sparsely inhabited, growth outside the bounds of the old city in the 19th and 20th centuries resulted in urbanization in many parts of the old canpo, and the vast majority of Montecara's population now lives there. There are two types of local government unit in Montecara: sieteri and vilà. Collectively, these are known as communes (comùni). The two types are identical in function, the difference being that the çìta is divided into six sieteri, while vilà are found in the canpo.

Each commune has a communal board (mésa comunà) with between five and nine elected members which is responsible for governing on the most local matters. Board members receive a stipend for their service and are allocated a small budget to spend at their discretion. In a system parallel to that of the national government, the communal boards function as local executives while the commune as a whole has the power to make decisions by public vote. Communes have the power to decide on certain planning matters, such as the construction, redevelopment, and demolition of buildings, and work with the national government to address problems affecting local residents such as trash, noise, and petty crime, and also serve as statistical areas and units for the distribution of public utilities such as water and electricity. Communal boards are also responsible for recruiting and maintaining a local unit of the Vigìlia, the volunteer police auxiliary organization.

Public safety

Law and order are maintained by the Dragòni, a branch of the Public Force, and by the civilian auxiliary service, the Vigìlia.

The Dragòni is an armed paramilitary force responsible for ordinary police work among the civilian population, guarding Montecara's coasts and ports of entry, policing the military, protecting Montecaran diplomatic missions, staffing the city-state's prison, and serving as an anti-terrorism force. Its elite unit, responsible for protecting public officials and important public buildings, is the Brigàda di Coraçièri. There is a persistent problem with organized crime in Montecara which a dedicated section of the Dragòni is dedicated to combating.

The Vigìlia is a volunteer auxiliary service that serves mainly as a neighborhood watch, improving public safety by providing "eyes on the street" and shortening response times. Volunteers receive basic training in conflict de-escalation, first aid, and other fundamental policing skills and patrol in their own local areas, building relationships with members of the community of which they are a part. They are unarmed but sometimes carry pepper spray and flexible restraints if dangerous situations are anticipated.

Ambulance, firefighting, and search and rescue services are provided by the Spartòli. Its members are expected to work not only as a professional lifesaving force but as an embedded civil defense corps, preparing their neighborhoods for disasters and taking the lead in the event of a crisis. Montecara's defense policy is based on the idea that the whole population must be able to provide for its immediate needs in an emergency, so the Spartòli maintain an auxiliary of trained civilians who are responsible for aiding in a first response; they are in turn expected to lead and assist their neighbors and coworkers so that the entire population can stay resilient. Every household in Montecara is issued an instructional booklet detailing civil defense procedures at regular intervals, and the state maintains a multi-channel alert system that includes public sirens and loudspeakers, radio and television broadcast interruption capabilities, and mass text messaging.

Military

Montecara's military is known as the Public Force (Fòrça pùblica). It consists of approximately 5,600 sailors and soldiers and has an integrated command structure with two main branches: the Brigàda Montecarà (land forces) and Armàda (navy). Montecara practices conscription for a term of 18 months usually beginning at graduation from secondary school at age 18. All able-bodied citizens and permanent residents, male and female, are eligible.

Foreign relations

Montecara's foreign relations strategy is based on four fundamental pillars: defense, diplomacy, economics, and culture. These four sources of power, used in concert, enable Montecara to exert an influence on international affairs that it disproportionate to its small size. It is a founding member of the Community of Nations and its subsidiary committees and organs. A Montecaran, Giove Andriola, served briefly as the interim Secretary-General of the Community of Nations after the death of Seán Fitzgerald in 1961.

Montecara enjoys good relations with its immediate neighbors in Euclea, particularly the nations of the Euclean Community. While it is not an EC member state, it is in the EC customs area and cooperates in defense and judicial matters. Relations with its other immediate neighbor, Tsabara, have often been strained because of persistent illegal migration and have further deteriorated as a consequence of the ongoing Tsabaran Civil War.

Foreign and signals intelligence services are provided by the Executive Directorate for Strategic Operations (DEOS). The investigation section of the Dragòni handles domestic intelligence.

Economy

The Borse Mercànte on a trading day | |

| Currency | Montecaran libra (MCL) |

|---|---|

| 1 April – 31 March | |

| Statistics | |

Population below poverty line | |

Labor force | (79% participation rate, 2017) |

| Unemployment | |

Main industries | finance, tourism, shipping |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods | luxury items, precision tools, medical instruments, pharmaceuticals |

| Imports | |

Import goods | foodstuffs, fuel, vehicles, consumer goods |

Gross external debt | |

(226% of GDP, Q4 2019) | |

| Public finances | |

(82% of GDP, Q4 2019) | |

| Revenues | ($30,236 pc, 2019) |

Montecara has a highly specialized, developed, and advanced social market economy. It consistently ranks at or near the top of international surveys on the ease of doing business, low taxation, and per-capita foreign investment. Finance, tourism, and shipping are the three biggest industries. There is a small but high-value-added manufacturing sector which produces mainly niche products. The primary sector is quite limited given Montecara's small land area, and is focused on high-value agriculture and fishing. Because its economy is so integrated into the global financial market and reliant on international trade, it is known as a bellwether for the financial health of the world at large. The trade openness ratio is 201.13%, making Montecara the most trade-dependent country in the world. Because Montecara is a free port and major entrepôt, the state directly profits on trade by assessing landing and docking fees and selling fuel and other supplies to ships, while allowing goods to be temporarily offloaded into the Port of Montecara and re-exported without assessing tariffs.

The Bànca de Montecara is the city-state's central bank and issues the libra (code: MCL; symbol: Ł), the national currency. The Bànca, aside from issuing currency, also performs certain financial regulation duties. The stock and bond exchange, the Borse Mercànte de Montecara, is the oldest in the world and lists domestic joint-stock companies as well as local and foreign debt securities.

Montepietà is the state's sovereign wealth fund, responsible for a portfolio of investments in securities and real estate. It traces its lineage to a mount of piety founded in 1213, making it one of the world's longest-running commercial enterprises. An institutional investor, it derives income from its portfolio of securities and real estate as well as investments in foreign exchange and private equity. Profits earned on Montepietà's investments are transferred to the Montecaran state treasury and used to fund the government, particularly the public welfare programs managed by the Secretariat of Social Protection such as Sànita Montecarà, pensions, and income support. This arrangement allows Montecara to have very low tax rates compared to other nations while securing a reliable source of income. Stock in Montepietà is not sold as the Montecaran state is the sole owner of the enterprise, but the institution can and does issue bonds to raise additional funds for investment. During fiscal year 2017, Montepietà had Ł2.5 trillion in assets and earned Ł109.6 billion in profit, a return of 4.32%.

Montecara is a major issuer of sovereign bonds and one of the world's premier venues for bond trading and clearance. One of the world's most in-demand securities is the Montecaran state bearer bond. These zero-coupon bonds are auctioned monthly and issued in paper form with a face value of Ł10,000 for a term of 10 years. Buyers may remain anonymous; this means that the bonds must be physically held, in essence functioning like cash. They offer the advantage of secrecy and the ability to hold a large value in a compact, portable, and fully negotiable format, but are controversial because of their obvious advantages to those engaged in tax evasion and organized crime.

Taxation

Controversially, Montecara is a well-known tax haven. It assesses no taxes on income, inheritances, dividends, or capital gains; instead, the state collects excises, tariffs, and taxes on corporations, land value, added value, along with a number of more minor transactions.

Finance

The financial sector is the largest and most important pillar of the Montecaran economy. Montecara has a centuries-long banking tradition, and its tax and banking secrecy laws make it an attractive location for financial institutions to incorporate. Major financial institutions include:

- Bànca Ultramarìn, merchant, commercial, and private banking

- Borse Mercànte de Montecara, the stock, commodities, and foreign currency exchange

- Crèdit Montecarà, commercial and private banking

- DeCraxi s.a.i., a financial services company known for its sovereign credit rating system

- Sicurasiò Xenèra (SX), one of the world's largest insurance and reinsurance markets

- SpFA, investment and merchant banking

Retail

Retail workers account for approximately 12% of the Montecaran workforce, and consumer spending in the retail sector amounts to approximately one-third of Montecara’s annual GDP. The retail sector includes businesses ranging from the highest-priced couturiers to the simple neighborhood sfumerìa, a traditional convenience store, the licenses for which are preferentially distributed to widows and the disabled in a scheme that dates back to the mid-18th century.

Montecaran trade unions, working in tandem with tradition-minded Solarian Catholics, have been successful in defending laws restricting working hours, especially on Sundays. With very limited exceptions, shops must be closed all day on Sunday. Only locations in Enrico Dulio International Airport and Pòrta Conìxia railway station may open, and then only for a maximum of eight hours between 8:00 and 18:00 and paying at least time-and-a-half wages.

Tourism

Montecara is consistently one of the top-ten destination cities in the world for international tourism by number of visitors per year. Its high density of cultural, artistic, and entertainment attractions has helped to make tourism a major component of the economy. Some of the most popular destinations for visitors include the famous casino, the city-state's plentiful and legal brothels, and the sights of the old city. Cruise ship docks, a major international airport, and a rail link to mainland Euclea have helped the tourist sector to grow exponentially since the early 20th century.

Infrastructure

Communications

Montecara has a modern telecommunications network, with all residents able to access broadband internet service as of 2012. Landline telephone, cable, and internet services are provided by Infotel de Montecara, a majority state-owned corporation. Montecara's country code for international telephone calls is +106, and the format for local numbers is +106-0000-0000. The international call prefix is 00. There are no area codes; individual numbers are randomly assigned, though it has been possible at various times to request a specific number if it is available. Postal services are provided by the state-owned Poste de Montecara.

Energy

Montecara has no fossil fuel sources and imports natural gas from Coius, particularly from Tsabara, for electricity generation, along with direct electricity imports from the EC. Annual electricity consumption is approximately 8.397 billion kilowatt hours in total, at 4,794 kW·h per person per year, as of 2017. The electricity industry and imports are regulated by the Secretariat of Planning and the Environment, and electric generation, distribution, and sales are handled by the cooperative Comega.

Because of its lack of fossil fuel resources, transitioning to renewable energy is a major focus, as is energy conservation. The government has the stated goal of making the city-state 100% free of fossil fuels by 2025, though it is not on track to meet this goal. Leaded gasoline has been banned since 1963. The coastal shelf to the south of the main island has strong winds and currents which are now being utilized as energy sources. Montecara's first wind turbines were built there in the 2013, and there are currently plans to further develop sea-based wind power. A waste-to-energy plant which uses combustible non-recyclable waste to generate approximately 400 GW·h of electricity per year was completed in 1997. Montecara is a nuclear-free zone, though it allows allied nuclear-powered naval ships to make calls in its port. Comega has allowed net metering since 2006, which has encouraged the development of privately built and operated wind and solar systems.

Transport

Montecara has a comprehensive and well-developed modern transportation network with robust connections to mainland Euclea. Public transit is provided by VM, which operates tram, ferry, and bus networks and a bicycle share system. Trenalia operates regional rail routes within Montecara and to nearby destinations in Euclea, as well as inter-city rail routes that connect with points beyond. The hub of the passenger rail system is Montecara Pòrta Conìxia railway station.

The Montecaran government strongly discourages private car ownership due to the dense nature of the city-state and a desire to avoid pollution. The number of license plates issued is capped and new plates are only issued through an auction system. Vehicles are banned in the old city with the exception of bicycles and certain electric vehicles due to the extreme narrowness of many streets and the often fragile pavements. This has preserved Montecara from destruction in the name of road expansion and keeps air quality high. The urban core of Montecara thus remains a very walkable and compact environment.

Montecara has some of the most arduous driver licensing requirements in the world. Licensees must be between the ages of 18 and 79 inclusive, and must pass a medical exam (including vision test), take a classroom-based driving theory course, complete an in-car course with a certified instructor, and then pass written and practical tests. First-time applicants, if successful, are granted a probationary license valid for two years which will be revoked if the driver accrues more than two violations of the traffic code. The medical and written exams must be passed again every other year for the license to be renewed.

All vehicles registered in Montecara must pass annual safety and emissions tests, and may not be more than ten years old. There is a high excise tax on petroleum fuel. Traffic drives on the right according to priority to the right, and only left-hand-drive cars are legal to operate in Montecara. There were 42 traffic-related fatalities in Montecara in 2017, a rate of 2.4 for every 100,000 inhabitants.

Montecara's transport network relies heavily on bridges and tunnels, both to connect the city-state with the rest of Euclea and to provide connections across internal waters. The Pont Vespàxi carries road and rail across the Bay of Montecara, while the Cross-Strait Tunnel connects Montecara with mainland Euclea.

There is one airport, Montecara–Enrico Dulio International, which serves as the hub for flag carrier Aeracara. The airport and seaport are operated by the government-owned Porti de Montecara.

Water

Montecara depends almost completely on the water that fills the caldera of its namesake extinct volcano. While the amount of water in the caldera fluctuates from season to season and year to year, it averages approximately 3 km3, enough to support an average water use of approximately 650 m3 per person and still be replenished from rainfall. Water condenses more readily at higher elevations and infiltrates the porous karst bedrock, where it pools and can then be channeled away, which also aids in replenishing supplies.

Because they have always been so acutely dependent on limited water resources, Montecara's people have developed inventive ways of making use of what they do have and conserving whenever possible. The principal method for transporting water from the caldera to farms and homes is traditionally the levàda, a stone channel cut into the slopes of the mountain. The levadà run both on the surface and in underground galleries, both of which also furnish popular hiking trails alongside their routes. Historically, neighborhoods that enjoyed levàda water were greatly preferred to those which had to rely on well water, which tended to taste salty and stale; water-carrier was once a common job in these areas. There is also a local history of using greywater that goes back to the time of the Solarians. One technique that has been in continuous use since that time is to organize houses and apartment buildings around a central courtyard garden that is irrigated with wastewater from sinks and washing, which provides better air quality, cools the building, and naturally treats the water. New toilet installations since 1995 have been required to use seawater to ease the strain on the drinking water supply.

Demographics

Ethnic composition of Montecara (2019)

Religious adherence in Montecara (2019)

Montecara's total fertility rate is 1.4, giving it a natural growth rate of -1.25% per year. On average, women have their first child at age 27. Net migration results in a gain of approximately 11,000 immigrants per year. If current trends continue, Montecara's population will peak at approximately 2.19 million in 2058. From that point, it will gradually decline until reaching an equilibrium of approximately 1.32 million around 2270.

Ethnicity

Montecaran society is divided between ethnic Montecarans, who comprise approximately three-fifths of the population, and foreigners, who are usually non-citizens and come temporarily to work. Montecarans are a Solarian people related to many other ethnicities in Euclea. They trace their lineage back to the population that lived in Montecara at the time of the Solarian Republic and speak Montecaran, a Romance language, as their common tongue. Solarian Catholicism is their dominant religion.

Immigration and its attendant effects on culture and identity is an issue of paramount importance in Montecaran society and politics. The Montecaran state has on many occasions publicly acknowledged the need for immigrant labor, especially in low-skilled jobs, but at the same time has gone to considerable lengths to protect what it feels is an essential and perhaps imperiled Montecaran identity.

Language

Montecaran is the sole official language. It is spoken at home by almost all citizens but only about 10% of non-citizen permanent residents. Gaullican is a compulsory subject in school and is nearly universally understood by Montecarans as a second language.

Religion

Solarian Catholicism is followed by the vast majority of Montecarans and many immigrants from neighboring Euclean countries. There are large minority populations following Irfan and Atudism. Irreligion has grown significantly since the early to mid-20th century, with nearly one in five residents of Montecara now professing no religious faith.

The Patriarchate of Montecara is the diocese of the Solarian Catholic Church in the city-state. It serves a local population of approximately 1.3 million Catholics, about three-quarters of all residents of the state. It was established in the early third century by the bishop Cuniculus at a time when Sotirian Catholicism was still largely an underground movement and was raised to the status of an archdiocese the following century. Five Montecarans have served as Pope, most recently Urbanus XI from 1787 to 1799.

The status of Irfan and Atudism is highly controversial in Montecaran society. The Popular Assembly has overwhelmingly voted to ban circumcision and other forms of genital cutting, covering one's face in public, loudspeakers on religious buildings, the ritual slaughter of animals and the importation of ritually produced meat, and non-state religious courts or arbitration panels, and all of these measures have passed into law with the approval of the Senate. All forms of polygamy and polygyny are strictly illegal, as is cousin marriage. Adherents of Irfan and Atudism often hold much more socially conservative beliefs than do native Montecarans, especially in regard to LGBT rights, feminism, and the use of alcohol and drugs, which has brought them into conflict with the majority population at various times. Furthermore, the perceived self-segregation of these communities and their far higher birthrate than native Montecarans has led to a public debate on whether to more aggressively assimilate them into mainstream Montecaran society, and if so, how to go about doing so.

Education

Education in Montecara is divided into five stages: preschool, primary, lower secondary, upper secondary, and tertiary. School attendance is compulsory between the ages of 6 and 16. There are public and private schools at the upper secondary level and below.

Gaullican language is a mandatory subject for Montecaran students at least through the secondary level. Students who have proven their proficiency in Gaullican and are native or fluent in Montecaran may study an additional foreign language. Common options include Badawiyan, Estmerish, Narodyn, Senrian, Vespasian, Weranian, and Xiaodongese.

A student's prior academic record and teacher recommendations determine whether he or she may advance from the lower secondary level to the liçeo, the university preparatory form of upper secondary school. The alternatives to liçeo are scuol xenèr (general-education school), which places a greater emphasis on life and workplace skills and does not have a specifically preparatory curriculum, or scuol tenicà, which provides a vocational education in addition to a foundational academic curriculum.

Aspiring university students may take the Matùra at the end of their secondary education. Performance on this test determines whether a student may even apply to the University of Montecara, and is also used by foreign universities and colleges to determine admissions qualifications. The Matùra covers Montecaran language and literature, Gaullican language, sciences and mathematics, civics and government, arts and humanities, and history. A qualifying score consists of at least a 3 out of 5 on a majority of the test's sections.

The standard grading system, used for students from primary school through the graduate level, is on a scale from 1 (low) to 5 (high). Cases of academic dishonesty may be dealt with by assigning the special grade of 0.

Stages highlighted in yellow below are compulsory.

| Level | Name | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Preschool | Crèxe | 3 years (age: 3 to 6) |

| Primary education | Scuol primàr (Primary school) | 5 years (age: 6 to 11) |

| Lower secondary education | Scuol segònd (Lower-grade secondary school) | 3 years (age: 11 to 14) |

| Upper secondary education | Liçeo (University preparatory school) | 5 years (age: 14 to 19) |

| Scuol xenèr (General education) or Scuol tenicà (Technical or vocational education) |

3 or 5 years (age: 14 to 17 or 14 to 19) | |

| Tertiary education | Làurea (Bachelor's degree) | 3 years |

| Magistrà (Master's degree) | 1 or 2 years | |

| Dotoràt (Ph.D.) | 3, 4, or 5 years | |

| Dotoràt medicinàl (M.D.) | 6 years |

Higher education is only provided through the state. There is one university in the city-state, the University of Montecara, founded in 1291. The university is organized into 21 colleges, which are themselves divided into 38 faculties.

Colleges of the University of Montecara:

|

|

|

Matriculating students apply to one or more specific colleges within the University and take only courses within their given college when enrolled. Students may, at the discretion of the instructor, audit courses from outside their college, but no credit is given.

Officers in the Montecaran military can receive additional military education at the Academìa militàr de Tornèa, and officer candidates are often co-enrolled at Tornèa and the University of Montecara.

Health

Healthcare is provided by the state free of charge to all legal inhabitants in and visitors to Montecara. The state health program, Sànita Montecara, owns public hospitals and clinics, buys drugs wholesale, pays medical staff salaries, and covers all other expenses associated with patient care. The health system was previously the responsibility of the Solarian Catholic Church but has been in state hands since it was nationalized in 1939.

Montecara enjoys the highest life expectancy of any country at 84.5 years overall, 86.4 years for women and 82.4 years for men. Healthcare spending amounted to 9.5% of GDP in 2017. There are 8.28 hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants, 14,503 beds in total. Montecara has the highest ratio of physicians per inhabitants in the world, at 7.21 per 1,000. As with all university education in Montecara, medical education is free of charge, and there is significant competition to work in the domestic healthcare sector. This promotes both a high number of trained clinicians and a high standard of expertise.

Prescription drugs are free of charge. Over the counter drugs must be paid for out-of-pocket. Both prescription and over-the-counter drugs may only be sold at licensed pharmacies (apotecà), which except in the case of those at public hospitals are privately owned. Elective treatments such as cosmetic plastic surgery are conducted only by private physicians and must be paid for out-of-pocket.

As an independent republic, Montecara long had institutions to care for the sick and needy. The oldest still in operation is the Ospedàl da Pìeta, founded in 1508 as a charitable hostel for the sickly poor. The Ospedàl Marìn (Naval Hospital), founded in 1680 to meet the needs of ill sailors, is one of the world's leading research institutions for tropical diseases and nutrition. The University of Montecara Hospital, which is owned by the University of Montecara but jointly operated by the University and Sanità Montecara, is the main teaching hospital.

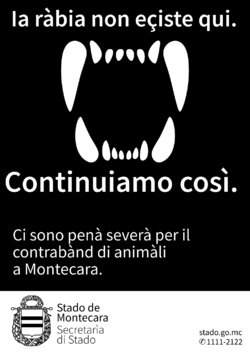

Montecaran public health authorities have waged several successful disease elimination campaigns dating back to the 1930s. Rabies, malaria, cholera, yellow fever, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, and diphtheria have all been eliminated locally, and only seven cases of imported tuberculosis have been reported since 2000.

Culture

Montecara has a Solarian culture that highly values aesthetics, a rich social life, and liberality, among other ideals. It is personified by Dòna Cara, depicted as a woman wearing a mural crown representing the city's walls. It is her face that the country's namesake mountain is supposed to resemble. Other national symbols include the xinòta tree, which bears the sour citrus that is a common flavoring for drinks and sweets, and the pygmy goat, which although unofficial is widely thought of as symbolic of Montecara as well.

Art

Montecara has a strong fine-art tradition, particularly exemplified by the paintings produced during the Montecaran Golden Age of the 14th and 15th centuries. Montecaran art was known in this period for its use of vivid color and majestic subject matter, including classical themes and rich interiors. Tixàn Vecèlo is perhaps Montecara's most famous painter, and his masterpiece, Neptune Offering the Wealth of the Sea to Montecara, hangs in the Palaço Pùblico.

The Palaço dei Doxi, the former palace of the Doxe of Montecara, is now a museum with a collection ranging from ancient times to the present day. The Galerìa Sufrèxi, one of the world's most visited museums, houses one of the world's finest collections of Solarian, Medieval, Renaissance, and Neoclassical art. Begun as the private collection of a wealthy merchant, it is now publicly owned.

Architecture

The Montecaran architectural tradition stretches back to the Solarian Republic, which brought its expertise in engineering to the city. Traces of Solarian architecture, including extensive brickwork, arches, vaults, stucco exteriors, mosaic floors, and wall frescoes can still be seen in contemporary buildings.

Montecaran architecture developed its own style beginning in the late 12th and early 13th centuries under the influence of the master Arnòld di Buçhe, whose treatise Principia architecturae (Principles of Architecture) is still recognized as a world masterpiece in itself. The main body of his work consisted of villas for Montecara's senatorial and patrician class, most of which are still standing.

Architecture has generally been well-preserved. It is illegal to demolish or substantially alter historic structures, and building designs must be approved by the state architectural review board before construction. Except for in industrial areas, Montecara has a remarkably coherent architectural vocabulary that remains true to its traditions.

Cuisine

Montecara must import nearly all of its basic foodstuffs because of its lack of arable land. It does, however, harvest a great deal of seafood, which is reflected in traditional dishes. The limited farmland is devoted to high-value crops suitable to the climate, mainly grapes (mainly for wine production), citrus, coffee, saffron (zafràn), and flowers.

Montecara's access to the sea and long culinary tradition has led to a great variety of specialties making use of local ingredients. Cuttlefish braised in ink, fried sardines, and bixàto, or roast eel, are all typical dishes. Fowl is also a traditional favorite, especially duck and other water birds, and duck eggs are still more popular than their chicken-borne counterparts. Songbirds were also eaten in large numbers up to the 1980s, when their capture was banned by environmental legislation. Montecara is on a major flyway, so stakes covered in birdlime (vignòla) were used to catch birds for culinary use. Though illegal, it is reportedly still possible to find some chefs who will prepare songbirds in the traditional manner. Meat from land animals is a small part of the diet and consists mainly of goat and pork, though cheese (mainly goat-based) is ubiquitous. The principal cooking fat is duck fat, with olive and sunflower oils assuming lesser roles.

Historically, rice (rixo) was the supreme staple food for Montecarans. There was always some domestic production, but Montecarans have relied on the sea trade for the bulk of their rice import for centuries. This is reflected in traditional dishes such as rixoto, a soupy preparation of rice simmered in broth, and rixi e bixi, rice and peas cooked together. In modern times, corn (biàva) is even more popular than rice, and is used to make bread, polènta, and many other dishes.

Montecarans generally have a light breakfast on the way to work or school at cafés or stalls located throughout the city. This often consists of a pastry, sandwich, or fruit accompanied by coffee or juice. There is a traditional mid-morning break for coffee around 11:00, and shops and offices often close briefly to allow for this. Lunch, usually the largest meal of the day, is eaten around 14:00 to 15:00, and workers generally take a full hour to do so, often eating at home. Dinner is eaten at about 21:00.

Montecara produces wine in a range of styles and varietals, but by far the most popular type, and the one most closely associated with Montecara's culinary identity, is xàca, a fortified wine made from white grapes. Three varietals enjoy protected status as heirloom crops in Montecaran law, all white grapes: Garganèga, Verdùxo, and Spaiòl. Garganèga is used to make still wine noted for its lemon and almond notes, Verdùxo is favored for the sparkling white Caràxa, and Spaiòl is used to make both a golden dessert wine with notes of honeysuckle and apricot and a light, acidic still wine. All three are used to make xàca, which can range in color and sugar content from nearly clear and dry to almost black and very sweet. Under Montecaran law, only wine that is produced from 100% domestic grapes can be sold as "Montecaran wine" (vin Montecarà). Montecara has high per-capita alcohol consumption rates, and in addition to wine, beer and spirits are popular.

Montecara is known for its sweets, notably xinòta-flavored marmalade and hard candy and formàxo giàço, a frozen dessert and snack similar to ice cream that is flavored with soft cheese and usually served in a split-open sweet bun (brioxa).

Special foods are eaten around Easter. These include galani, a rum-flavored fried pastry served with lemon zest, and pandòr, a sweet egg bread. Easter lunch traditionally includes a feast of seven different types of fish, the exact components of which vary but which generally include clams, scallops, salt cod, anchovy, and sea snails.

Media

Montecara's state-owned television and radio broadcaster is Telèradio Montecara. It operates three television and two radio channels and is supported by a license fee applied to cable television, Internet service, and cellular data bills.

Of Montecara's four domestic newspapers, the most circulated is Il Finansiér, which publishes financial news. Its international Gaullican-language edition is distributed worldwide.

Music

Montecara has a strong operatic and orchestral musical tradition dating back to the first operas written in the early 17th century. Indeed, because the arts in republican Montecara were supported by public funds rather than by wealthy patrons, it was until the late 18th century the only place in the world where opera could be seen by the general public, who were able to simply buy tickets.

The main venue for opera performance is the Càxa da Òpera, a 19th-century house that premiered the works of Montecara's most famous composer, Giacopò Verxì. It still hosts regular operatic performances throughout the year. A classical conservatory, the Academìa da Mùsica, fosters young musicians.

Sport

Association football is by far the most popular participant and spectator sport in Montecara. The top men's teams are the Montecara national football team, nicknamed the "King-Killers" (I Matarrè), and SDB Montecara, the top professional football club.

Before the advent of football in the early twentieth century, Montecarans enjoyed traditional sports and games, some of which still survive, albeit with reduced popularity. Xugo da bilòta, commonly known in other countries as Montecaran bilota, is a handball game played against a wall by teams or individuals and is still frequently played by children in Montecara's narrow streets and as a betting game at the frontò associated with the state casino. Bòxio is a bowling game traditionally played on wet beach sand at low tide.

Montecara is also host to an indoor velodrome and swimming facility and the historic grass tennis courts at the Club Raquèt de la Croxa.

Holidays

Every Sunday is a public holiday in Montecara in addition to the other declared holidays. Public holidays are mandatory in Montecara, with shops, businesses, and public institutions required to close. Workers in Montecara typically receive at least four weeks' paid vacation time per year in addition to public holidays.

| Date | Name | Montecaran name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 January | New Year’s Day | il Capodàn | Also the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God. |

| 6 January | Epiphany | ia Epifània | |

| 10 February | Victory Day | Fèsta da vitòria | Commemorates victory ending the Great War. |

| The Friday before Easter | Good Friday | Sànta veneri | |

| Movable Sunday between 22 March and 25 April | Easter Sunday | Pàscua | |

| The day after Easter | Easter Monday | Pasquètta | |

| 16 April | Regicide Day | Fèsta di rexeçìdo | National day. Commemorates the assassination of dictator Piero de' Malatesta on this date in 515. |

| 28 April | Liberation Day | Fèsta da liberaxòn | Commemorates the end of the Gaullican occupation in 1935. |

| 1 May | International Workers' Day | Fèsta dei lavoratòri | Commemorates the achievements of workers and the labor movement. |

| Thursday 39 days after Easter | Feast of the Ascension | Fèsta da ascenxiò | |

| Monday 50 days after Easter | Pentecost Monday | Luni di Pentecòst | |

| 15 August | Assumption of Mary | Fèsta da asunxòn de Marìa | |

| 1 November | All Saints' Day | Ognisànti | |

| 8 December | Feast of the Immaculate Conception | Fèsta da conxeptimènt inmacolàda | |

| 25 December | Nativity | Nadàl | |

| 26 December | Feast of Saint Stephen | Fèsta di San Stefàn |