Etruria: Difference between revisions

| Line 267: | Line 267: | ||

While the regime focused on destroying the separatist threat and maintaining Etrurian territorial integrity, it instituted a series of economic reforms led by financial experts and economists, who together formed the [[National Institute for Economic Reconstruction]] (INRE). The INRE was granted extraordinary powers by the military to seize property, businesses and land for purposes geared entirely toward promoting economic and wage growth. The military also launched a series of anti-corruption and mafia drives that proved somewhat successful at expelling waste, misappropriation and organised crime from the economy. However, it was later discovered that the military had relied upon several mafia groups for financing and its own corrupt practices. Aided by a cheap currency and low wages, the military backed INRE’s policy of sponsoring manufacturing industries, which by 1984 had turned Etruria into one of the fastest growing export economies. However, INRE and the military’s pro-statist approach to economics failed to deliver the rocket-speed growth necessary to see the two-decade gap between Etruria and its neighbours closed. One area of success what the government’s ability to secure investment from Euclean governments, regularly achieving such by warning that economic collapse would see Etruria fall to socialism. | While the regime focused on destroying the separatist threat and maintaining Etrurian territorial integrity, it instituted a series of economic reforms led by financial experts and economists, who together formed the [[National Institute for Economic Reconstruction]] (INRE). The INRE was granted extraordinary powers by the military to seize property, businesses and land for purposes geared entirely toward promoting economic and wage growth. The military also launched a series of anti-corruption and mafia drives that proved somewhat successful at expelling waste, misappropriation and organised crime from the economy. However, it was later discovered that the military had relied upon several mafia groups for financing and its own corrupt practices. Aided by a cheap currency and low wages, the military backed INRE’s policy of sponsoring manufacturing industries, which by 1984 had turned Etruria into one of the fastest growing export economies. However, INRE and the military’s pro-statist approach to economics failed to deliver the rocket-speed growth necessary to see the two-decade gap between Etruria and its neighbours closed. One area of success what the government’s ability to secure investment from Euclean governments, regularly achieving such by warning that economic collapse would see Etruria fall to socialism. | ||

By the mid-1970s, the victory over the separatists and the improvements to Etruria’s economic wellbeing resulted in the military government achieving a high watermark for popularity. The military’s use of extensive Etrurian nationalist propaganda campaigns would further fuel the resurgence and resilience of the country’s far-right. Many Etrurians were willing to forego their civil liberties for security and prosperity. However, by 1976 much of Etrurian society viewed the defeat of the far-left separatists as a mission accomplished for the military government and the adoration soured. In 1977, students protested censorship and were met with live gunfire by military police, which soon escalated into a nationwide protest, in a major concession, Chief of State [[Gennaro Aurelio Altieri]] announced his intention to lead negotiations with civil society groups for the eventual restoration of democracy. In 1983, the military and the [[United Committee for Democracy]] secured an agreement for the restoration of democracy. While the military would step down peacefully and withdraw from politics, the UCD conceded to the military, | By the mid-1970s, the victory over the separatists and the improvements to Etruria’s economic wellbeing resulted in the military government achieving a high watermark for popularity. The military’s use of extensive Etrurian nationalist propaganda campaigns would further fuel the resurgence and resilience of the country’s far-right. Many Etrurians were willing to forego their civil liberties for security and prosperity. However, by 1976 much of Etrurian society viewed the defeat of the far-left separatists as a mission accomplished for the military government and the adoration soured. In 1977, students protested censorship and were met with live gunfire by military police, which soon escalated into a nationwide protest, in a major concession, Chief of State [[Gennaro Aurelio Altieri]] announced his intention to lead negotiations with civil society groups for the eventual restoration of democracy. In 1983, the military and the [[United Committee for Democracy]] secured an agreement for the restoration of democracy. While the military would step down peacefully and withdraw from politics, the UCD conceded to the military, legal immunity for all regime officials and leaders. The future democratic system would retain the military’s ban on political parties or societies dedicated to promoting non-Etrurian nationalisms and the right for the security services to shutter media outlets, groups or societies promoting the same. | ||

On the 1 July 1984, Etruria held its first democratic election since 1958. The centre-left [[Social Democratic Party]] under [[Miloš Vidović]], the first Novalian to serve as President, won the largest share of seats and entered into coalition government with [[Sotirian Democracy]]. | On the 1 July 1984, Etruria held its first democratic election since 1958. The centre-left [[Social Democratic Party]] under [[Miloš Vidović]], the first Novalian to serve as President, won the largest share of seats and entered into coalition government with [[Sotirian Democracy]]. | ||

Revision as of 20:07, 12 August 2020

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

United Etrurian Federation

3 other official names

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Motto:

| |||||||

Anthem:

| |||||||

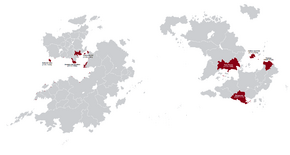

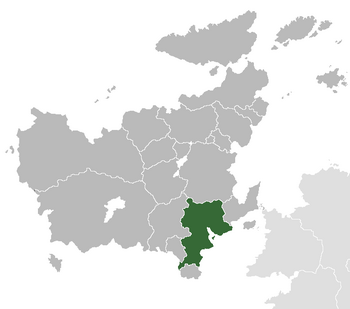

Location of Etruria (in light green), within Euclea (light grey) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Capital | Povelia | ||||||

| Largest city | Tyrrhenus | ||||||

| Official languages | Vespasian Novalian Carinthian | ||||||

| Ethnic groups (2016) |

| ||||||

| Demonym(s) | Etrurian | ||||||

| Government | Constitutional parliamentary federal republic | ||||||

| Francesco Carcaterra | |||||||

| Vittoria Vasari | |||||||

| Ivano Balić | |||||||

| Legislature | Senate of the Federation | ||||||

| State Council | |||||||

| Chamber of Representatives | |||||||

| Formation | |||||||

| 1783-1784 | |||||||

| 20 January 1784 | |||||||

• Monarchy restored | 3 April 1810 | ||||||

| 10 May 1888 | |||||||

• Treaty of Kesselbourg | 12 February 1935 | ||||||

• Current constitution | 1 July 1983 | ||||||

| Area | |||||||

• | 548,549 km2 (211,796 sq mi) | ||||||

| Population | |||||||

• 2020 estimate | |||||||

• 2014 census | 63,888,987 | ||||||

• Density | 119.58/km2 (309.7/sq mi) | ||||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate | ||||||

• Total | |||||||

• Per capita | |||||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate | ||||||

• Total | |||||||

• Per capita | |||||||

| Gini | 46.9 high | ||||||

| HDI | 0.843 very high | ||||||

| Currency | Etrurian florin (₣) | ||||||

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy | ||||||

| Driving side | left | ||||||

Etruria, officially the United Etrurian Federation or UEF (Vespasian: Federazione Etruriana Unita; Novalian: Sjedinjene Etruriska Federacija; Carinthian: Združena Etruriska Federacija) is a sovereign parliamentary federal republic, made up of three constituent states: Vespasia, Novalia and Carinthia and six autonomous federal regions; Carvagna, Torrazza, Ossuccio, San Eugenio and Tarpeia, and several islands, the largest being Aeolia and Apocorona. Etruria is located in southern Euclea. Its is bordered (clockwise) by Amathia to the north, Gaullica to the north-east, Florena to the east, to south, Gibany to the south, and Piraea to the west. Etruria is home to 65.5 million people, its federal capital is Poveglia and largest city is Tyrrhenus.

Since classical times, its central geographic location in Euclea and the Mazdan and Solarian Seas, Etruria has historically been home to a myriad of peoples and cultures. In addition to the various ancient Vespasian tribes and Vespasic peoples dispersed throughout the Etrurian interior and insular Etruria, beginning from the classical era, Pireans, XX and XX established settlements in the south of Etruria, with Vicalvii and Gaullics and Iberialcelts inhabiting the centre and the north of Etruria respectively. The Vespasic tribe known as the Solarians formed the Solarian Kingdom in the 8th century BC, which eventually became a republic that conquered and assimilated its neighbours, including the powerful and wealthy Viclavii. In the first century BC, the Solarian Empire emerged as the dominant power in the Solarian-Mazdan Basin and became the leading cultural, political and religious centre of Euclean civilisation. The legacy of the Solarian Empire is widespread and can be observed in the global distribution of civilian law, republican governments, Sotirianism and the Solarian script.

During the Middle Ages, Etruria suffered sociopolitical collapse amid calamitous barbarian invasions, but by the 11th century, numerous rival city-states and maritime republics rose in Vespasia to great prosperity through shipping, commerce, and banking, laying down the groundwork for modern capitalism, however the areas of modern Novalja and Carinthia continued to decline. These independent statelets often enjoyed a greater degree of democracy and wealth in comparison to the larger feudal monarchies that were consolidating throughout Euclea at the time. By the 13th century, modern Etruria became dominated by three states, the Exalted Republic of Poveglia, Grand Duchy of Carvagna and the Ecclesiastical States.

The Renaissance spread across Etruria from Povelia, bringing a renewed interest in humanism, science, exploration and art. Vespasian culture flourished at this time, producing famous scholars, artists and polymaths such as "Great people". The influence and commercial power of the maritime republics began to dominate the monarchies of the interior, culminating in the Povelian victory in the Etrurian Wars and becoming the dominant power in Etruria, leading to the Pax Poveliae. Povelian colonisation of the Asterias soon followed, introducing New World treasures to Etruria. The sudden rise of the Principality of Tyrrenhus in the south added pressure to Povelia. In the 18th century, Povelia’s decline began, hastened by the immense cost paid during the Ten Year’s War. This decline led to the Central Etrurian Wars and the Torazzi War between Povelia and Tyrrenhus, bankrupting and disrupting vast swathes of Etruria. The famine, debt and corruption led to the overthrow of the monarchy in Tyrrenhus, sparking the Etrurian Revolution (1783-1785) and the establishment of the Etrurian First Republic, creating one of the earliest republics in history. The Republic would go on to unite Etruria and for the next fifteen years, engage in the Etrurian Revolutionary Wars, spreading republican tradition and values across southern Euclea. The constant warfare, poor governance and state-terror would lead to the restoration of monarchy in 1810 and the United Kingdom of Etruria.

From 1810 until 1880 would enjoy prosperity, growth and development. Etruria would establish one of the largest colonial empires, while federalism was greatly expanded and refined. However, debt, a poor economy and authoritarianism resulted in the 1880 Revolution and the establishment of the Second Etrurian Republic. Etruria was a major participant in the Great War, from which it emerged victorious, however, poor territorial gains and political instability led to the emergence of the Etrurian Revolutionary Republic and the Solarian War, which saw Etruria defeated. The Third Etrurian Republic emerged in the aftermath, rebuilding the country and establishing a fixed regime of civil rights and freedoms before being overthrown by the military which established a Junta in wake of the Western Emergency. Democracy would be restored in 1983 with the current Fourth Republic, this was followed by numerous liberalising economic reforms that achieved high sustained economic growth and improvements to standards of living. Between the 1990s and 2010s, the country underwent political reforms in aim of Etruria joining the Euclean Community. A referendum held on EC membership in 2016 was defeated due to several major corruption scandals and the successful No-campaign being led by the right-wing Tribune Movement, this ended all prospect of Etrurian membership of the EC. The loss of the referendum, coupled with the corruption scandals brought about the near collapse of the establishment parties in the 2016 election and a victory for the Tribune Movement, which formed the most right-wing government in Eastern Euclea since the Great War.

Today, Etruria has a mixed market economy based around finance, industry and agriculture. It has the XX largest economy in Euclea, and XX largest in the world. It is widely considered a newly-industrialised economy, a regional power and middle power. It is a council member of the Community of Nations, GIFA, NAC and the ITO.

Etymology

The assumptions on the etymology of the name "Etruria" are very numerous and the corpus of the solutions proposed by historians and linguists is very wide. Many historians note that the Etrurian mountain range that extends across northern Etruria and rising up east of Sea/Lake X then southwards along the border with Sardenya were prominent features of Vespasic faiths in ancient history. Etruria in ancient Vespasic (Etrúra) meant "Sacred Rock" and since the Aventine mountains meet the Etrurians roughly in the central region of the north and push south towards the X Sea, many historians surmise that as the Vespasic tribes expanded, they considered the Aventines and the Etrurians to be one and the same and extended the name Etrúra to the rest of the country. As Vespasic developed into latin, Etrúra evolved into Etruria and the name has remained in use since.

The term Transetruria or Transetrurian was only introduced in the 19th century to refer to Vespasia and its territories in Carinthia and Novalia and remained in use within officialdom, eventually being adopted as the official title of the federation in 1921, as a means of unifying the three constituent states.

History

Pre-history

Excavations throughout Etruria revealed a hominid presence dating back to the Palaeolithic period, some 210,000 years ago, modern Humans appeared about 48,000 years ago. Much of the pre-history presence is concentrated around the Poveglian Basin in the north and the Alluvian plains in southern Etruria.

The Ancient peoples of pre-Solarian Etruria– such as the Torians, the Vepasii (from which the Solarians emerged), Vicalvii, Otians, Samanians, Sorines, the Guallics, the Suratii, and many others. Other peoples were identified as the primarily mountainous, Novarians, Carumnii and the southern and coastal focused Aeoluii.

Between the 17th and the 11th centuries BC XX established contacts with Etruria and in the 8th and 7th centuries BC a number of XX colonies were established all along the coast of Vespasia and the southern part of the Aeolian Peninsula, that became known as XX. During this time, the Vespasii were rapidly growing in and around what would become Solaria, while north of them, the Vicalvii had cleared land around the seven-hills of Vicalvus.

Ancient Solaria and Tyrrenhus

Solaria, a settlement on the coast of the Bay of Lasa Vecuvia conventionally founded in 757 BC, was ruled for a period of 239 years by a monarchical system, initially with sovereigns of Vespasii and Torian origin, later by Vicalvii kings. The tradition handed down seven kings: Romulus, Verus Tanis, Horius Antonius, Marcus Marcellius, Eugenius Prascus, Ceserius Tullius and Hadrianus Lutorius. In 511 BC, the Solarians expelled the last Vicalvii king from their city and established an oligarchic republic, supposedly upon the order of the Aventine Triad, led by the sun gold Sol.

To the north of Solaria, Tyrrenhus, a settlement built around the ford of the Metaia River rapidly grew under a series of successive kings, it dramatically expanded its territories to cover the entire Vicalvian Plain. Vicalvus' dominant position allowed it to influence Solaria until the expulsion of Hadrianus Lutorius. With the establishment of the Solarian Republic, Vicalvus found a serious challenger to domination over southern Vespasia. The two cities would fight numerous wars known as the Wars of the Two Cities, the wars ended in 256 BC when Tyrrenhus was defeated at the Battle of Salutaria, resulting in the city's annexation by Solaria. Tyrennii culture would fuse with Solarian, creating the long-lasting Solarian culture that spread with the empire's growth. The Solarian Republic until the first century B.C. would expand to encompass all of modern day Etruria and western Auratia, crossing the Solarian sea to establish colonies on the coasts of Tsabara and northern modern-day Zorasan in 89 BC. This expansion would instigate centuries-long conflicts with the Heavenly Dominions.

In the wake of rebellion by Tarchon Parusna in the first century B.C. and a series of concurrent slave revolts, the Solarian Senate granted extraordinary powers to TBD, who with the assistance of allies within the senate, succeed in being granted the title of Emperor. Over the course of centuries, Solaria would expand and grow into a massive empire stretching from the western borders of Bahia to the southern reaches of Estmere and Swetania, and engulfing the whole Solarian basin, in which the Tyrennii-Solarian and Piraeo and many other cultures merged into a unique civilisation. The Solarian Peninsula was named Etruria was declared "Terra Saena" (Sacred Soil), granting special status compared to other imperial provinces. The long and triumphant reign of the first emperor, TBD, began a golden age of peace and prosperity. From its founding until the late 4th century CE, the Empire's leaders were relatively successful in maintaining a peaceful balance of power between the Emperor and Senate, while sporadic and isolated power struggles were recorded, this enabled to extend the period of prosperity.

In 395 CE, Mount Vecuvia erupted devastating much of the ancient city of Solaria, among the estimated 5,000 people killed was Emperor Diocletius. The Emperor's sudden death coupled with this as of yet declared successor sent the Empire spiralling into chaos, with numerous leading figures declaring themselves Emperor, sparking the Vecuvian Wars. The devastating localised and Empire-wide civil conflicts significantly weakened the central authority of the state, exacberating the strain of managing and protecting its vast territories. The near constant power-struggles between successive and short-reigning Emperors and the Senate hollowed out the central state, giving way to endemic corruption, poor provincial governance and economic malaise. This stagnation was coupled by ever growing threats, either from the Heavenly Dominions in northern Coius, to Marolevic, Weranic tribal incursions from the Euclean west and north. Between 417-419 CE, the Heavenly Dominion launched a full-scale invasion of the Empire's holdings in northern Coius, evicting the Solarian Empire from the continent for the first time since 66 BCE. Between 419 and 426 CE, the Empire rapidly lost control of its western holdings to numerous migranting Marolevic tribes, while Weranic tribes to the north descended southward toward the province of Gaullica. In 424, the Empire essentially collapsed within its heartland, with numerous Senators establishing individual powerbases, while two years later, Claudius of Gaullica redeclared the Empire, laying the foundations of the Verliquoian Empire. Within Vespasia, the Empire's heartland fractured into numerous fiefdoms and statelets, which would remain the case until the expansion of the Verliquoian Empire decades later.

The Solarian Empire was among the most powerful economic, cultural, political and military forces in the world of its time. It was one of the largest empires in world history. At its height under Velturius, it covered 3.4 million square kilometres. The Solarian legacy has deeply influenced the Euclean civilisation, shaping most of the modern world; among the many legacies of Solarian dominance are the widespread use of the Vespasic languages derived from the fusion of Tyrennii and Solarian, the numerical system, the modern Eastern alphabet and calendar, and the emergence of Sotirianity as a major world religion.

Middle Ages

After the Fall of the Solarian Empire and the fragmentation of Etruria, the former heartland was dominated by small states ruled by former Solarian senators and other aristocratic elites. The western reaches of Etruria, would fall under the dominion of numerous Marolevic tribes, who would over the course of several decades fighting fierce internecine wars, culminating into the future Kingdoms of Carinthia and Novalia. Efforts by the Empire of Arciluco to expand its dominion eastward to reclaim Solaria was repeatedly defeated by these Marolevic tribes, this in contrast to the Verliquoian Empire, which succeeded in restoring imperial control over much of Vespasia between 432 and 449 CE. Verliquoian rule would go on uncontested for over two-hundred years, until in 665, the patricians of the city of Povelia successfully negotiated independence from the Empire, despite imperial rule ever being nominal or superficial. The patricians and merchants established the Exalted Republic of Povelia the following year, and would result in the establishment of Povelia as one of Euclea's great powers during the Renaissance and early modern period. During this time of Verliquoian dominance, the numerous provinces that later form the numerous comunes and city-states of Etruria were established to ease imperial administration, another notable development was the ever growing autonomy of the city of Solaria under the direct temporal rule of the Papacy.

In 878 CE, the ruling Verliquoian Empire would enter into conflict with the migrating Tagamic Horde led by Chanyu Ekkin. The previous years had seen the Tagamics devastate much of the Second Heavenly Dominion as they fled the Great Steppe. The resurgent Third Heavenly Dominion in pursuit of the Tagamic migrations forced them across the Aurean Straits, bringing the conflict onto continental Euclea in 880. The Tagamics under Ekkin would reach eastern Vespasia in 882 and unleash a wave of destruction from Santa Maria in the east, to Povelia and ultimately Solaria itself. The highly successful intervention by Saint Chloé and Emperor Philippe II would save both Povelia and the Ecclesiastical City from certain destruction. The defeats of the Tagamics at Povelia and Solaria succeeded in evicting them from Vespasia, however, they would go on to travel north-west before settling in modern day Narozalica. The devastation unleashed would have serious effects on the demographic development of Vespasia, however, the success of the Vespasian provinces in self-defence (in some cases), and the costs paid by the Verliquoian Empire led to a steady decline in imperial authority, with some of its provinces rising up in wake of the Tagamic's expulsion, to the voluntary withdrawal of the Empire from other regions. In 888, the Empire awarded the Papacy jurisdiction over Solaria and its surrounding regions in what is known as the Emperor's Donation to Saint Peter. This was followed by the emergence of the Duchy of Carvagna, Duchy of Tyrrenhus and the Grand Duchy of Faulia. Around this time, the Marolevic tribes in the west unified to form the respective kingdoms of Carinthia and Novalia in 890 and 899, the latter would eventually fall to the Kingdom of Miruvia in 1035.

By the early 11th century, the previous decline in imperial authority, and the geographic separation between Etruria and the rest of the Verliquoian Empire via the Aventine Mountains led to the Vespasian Revolt in 1035, where the League of the Àdexe, led by Povelia rose up and defeated the Empire at the Battle of Tresano, guaranteeing the independence of the northern states of Vespasia. It was during this chaotic period that Vespasian towns and regions saw the rise of a unique institution, the medieval commune. Given the relative isolation from the rest of Euclea, the influence of already established Vespasian states to the south and the extreme territorial fragmentation present, numerous communities sought autonomous means of establishing law and order. The Revolt also saw the expansion of Povelia across the southern half of the Eugenian Plain, securing the island-city from land-based threats. The coasts of the Bay of Povelia saw an equally unique development during the middle ages, the emergence of thalassocratic city-states and the maritime republic. During the early centuries of the middle ages, the only cities to emerge of this type was Povelia, the Republic of Accadia and the Republic of Amelia. These cities would grow to eventually dominate the Solarian Sea and monopolise trade routes to between Euclea and northern Coius. All these cities during the time of their independence had similar systems of government in which the merchant class had considerable power. Although in practice these were oligarchical, and bore little resemblance to a modern democracy, the relative political freedom they afforded was conducive to academic and artistic advancement. However, over time Povelia would emerge as the undisputed maritime power, annexing Amelia in 1280 and greatly reducing the power and influence of Accadia by the middle of the renaissance, in wake of the War of the Bay. Povelia would emerge as the most powerful Vespasic state in 1450, following the War of the Amelian League, which saw it capture the island of San Francesco and almost the entirety of the Eugenian Plain. This was followed by the rapid expansion overseas, with the occupation of modern-day Galenia and the western coasts of Piraea. Through these acquisitions, Povelia was able to dominate the Euclean-Coian trade, establishing commercial outposts and colonies as far west as Satria. While the maritime republics flourished, so too did certain terrestial polities, primarily, the Grand Duchy of Carvagna, Principality of Tyrrenhus and the Grand Duchy of Faulia. Carvagna emerged as a capital of silk, wool, banking and jewelry and would emerge as the greatest rival of Povelia for domination over the Vespasian states.

The self-supporting wealth such business brought to Vespasia and the rest of Etruria, ostensibly through Miruvia's extensive trade with the city-states, meant that large public and private artistic projects could be commissioned. The Vespasian state first felt huge economic changes in Euclea which would lead to the commercial revolution: the rise of Povelia saw it able to finance the voyages and delegations to southern Coius; some of the first universities and academies were founded in the southern Vespasian states, giving birth to a new scholastic movement that would see some individuals achieve international and historical fame; the patronage of both the Ecclesiastical State and the city-states saw the emergence of capitalism and the great banking families of Stazzona, Faulia and Auronzo. In 1450, the so-called Concordat of Quaratica was signed by the major city-states, essentially establishing a treaty guaranteeing the current territories of the Vespasian region, the concordat also saw a universal commitment to defending Vespasian from foreign incursion, in what some view as the first collective defence agreement. The Concordat would maintain peace in Vespasia for over 150 years, deepening the degree of prosperity seen in the region. In the west, the Kingdom of Miruvia would benefit greatly from the prosperous Vespasian city-states, emerging as one of the most developed and wealthy of the Marolevic kingdoms in Southern Euclea, the kingdom under the Lazarević dynasty underwent a golden age. However, the Kingdom would collapse in 1577 with the Novalian and Carinthian revolts, which restored the kingdoms of Carinthia and Novalia.

Early Modern

The 15th and 16th centuries marked the emergence and peak of the Etrurian renaissance, collectively referring to the numerous Rinnovos, that marked the resurgence of Solarian culture, art and scientific advancement. The renaissance itself was mostly driven by the ceaseless rivalry between the Vespasian city-states, duchies and maritime republics, whose leaders patronised artists, sculptors, alchemists and mathematicians to “explore and bring glory.” Povelia became the heart of the Etrurian renaissance, with its rival states now formally under the domination of princely families and political dynasties, seeking to compete with Povelia. The consolidation of princely rule in the Vespasian states gave way to the first forms of modern governance, as opposed the feudalism of Euclea. The numerous Rinnovos allowed the Etrurian renaissance to enjoy a dominating influence on painting and sculpture, with the works of Andrea Farese, Giovanni Aldrovandini, Tiziano della Vadera, Andrija Vareši and Ivan Antonevic, enjoying legacies lasting to this day.

The peace that followed the War of the Amelian League and the Concordat of Quaratica preserved the borders and prosperity of the Vespasian states to such a degree that no conflict was recorded by 1450 and 1569, when a brief conflict erupted between Povelia and the Republic of Accadia after the latter attempted to regain control of San Francesco island and failed. With the mainland secured from threats, Povelia began to expand its holdings across the Solarian and Mazdan seas, establishing commercial outposts across Satria and northern Coius, while its hold over Nava secured its trade links to western Euclea. The increasing power of Povelia would bring it into conflict with the Gorsanid Empire in northern Coius, Gaullica to its north in Euclea and numerous Satrian states in Western Coius. Povelia’s rivalry with Gaullica while militarily confined to northern Etruria also spread to the Solarian Catholic Church, where it took the form of a battle for influence over the Papacy. Conclave became a theatre of this rivalry leading to the period of the Lion and Eagle period, in which sixteen consecutive Popes were either Povelian or Gaullican.

The victory of Povelia in 1450 saw the steady rise of the Council of Thirteen, as the supreme political authority in the republic, which essentially established one of the first directoral republics, and cementing Povelia’s status as an near authoritarian oligarchic republic with the loss of numerous ancient bodies and checks and balances. However, with the Council of Thirteen came an inherently streamlined administration and executive branch, this led to the end of commercial interests being the overriding concerns of government, to Povelia pursuing nominally identical objectives as the feudalistic monarchies of Euclea. Among these new developments was the desire for greater territory, resources and access to slaves to fuel the expansion of the Povelian navy and its need for free oarsmen. The second of the great Vespasian states, Carvagna, fell under the rule of the Cerini family who oversaw the rise of Carvagna as the leading financial capital of southern Euclea and through their patronage of the arts and sciences, turned Stazzona into one of Euclea’s leading cultural cities.

The Vespasian states would be transformed in the late 15th century with the discovery of the New World in the 1450s. Sensing an opportunity to greater trade opportunities and prestige for the Republic, Povelia’s Council of Thirteen would contract numerous navigators and explorers to map the coasts of the new continents. This culminated in the journey of Raffaelle di Mariran in 1522, who arrived in modern day Marirana in 1523. Honouring the Council’s desire for the Kingdom of Gold, he claimed the territory for Povelia, establishing the colony of Novo Poveja. This was followed by the establishment of settlements and outposts in Valorea. These events established Povelia as one of the first colonisers of the new world and with it, the vast resources of the Asterias. The new trade routes were expanded, developed and policed by Povelia’s construction of a fleet of new vessels, including the Caravela and galleon. The expansion of Povelian territory in Marirana came at a great cost to the native populations, while the Republic sponsored the settling of Marirana with citizens from across its dominions in the old world. Fears that rivals at home could interdict its trade routes, the Povelians launched the War of the Sea against the Gorsanid Empire, decimating its fleets in three consecutive battles between 1526 and 1528. The emergence of the Povelian overseas empire brought prosperity also to the Etrurian states neighbouring it. In order to expand its navy to meet its ever-growing needs, Povelia established closer trade ties with the Kingdoms of Novalia and Carinthia, importing vast quantities of wood, wool and iron. Povelia in turn looked to Carvagna for the financing of its overseas ventures, keen to preserve its own treasury for use at home. The traveling of goods across northern and central Etruria to feed Povelia’s burgeoning empire brought further prosperity to the smaller northern states, while the goods imported from the New World, including herbs, tobacco, and food stuffs were sold to Euclean and Etrurian markets alike.

In comparison to the Povelian prosperity, the central Vespasian states saw a period of instability, in part caused by the rise of competing families who grew in wealth through the new Povelian trade routes. In Carvagna, the reigning Cerini dynasty faced a growing threat from the Mazzi family, who’s banking, and merchant businesses profited considerably with links to Povelia and her colonies. Between 1523 and 1529, tensions between the two families had roiled the streets with thugs paid by the respective dynasties attacking one another, ransacking businesses and burning of goods. In 1529, having bribed palace guards, the Mazzi stormed the Palazzo Cerini in central Stazzona, exiling Duchess Elizabetta II from the city. However, the Mazzi dynasty’s rule over Carvagna would be short lived, when the Council of Citzens, an underground group led by independent merchants, scholars and clergy incited the peasantry to rise up and exile the Mazzi. The so-called Citizens’ Revolt, would be one of the first instances of popular revolution against an unpopular regime and would be a precursor to the Etrurian Revolution two and sixty years later. Between 1529 and 1538, Carvagna was ruled by a series of democratically elected Magistrates, until the Cerini were invited back to once against rule over the Grand Duchy. The instability in Stazzona gave way to similar citizens councils in the principalities of Torrazza and Tyrrenhus, though they failed to gain major traction.

Throughout the 17th century, the Kingdoms of Novalia and Carinthia faced off numerous revolts by Miruvian peasants and exiled nobles, seeking to re-establish the Kingdom of Miruvia. Beginning in the 1560s, the Novalians under King Petar IV crushed the Vetar Revolt, which led to the capture and execution of Count Dragutin in 1564. In 1567, the crisis of the succession of the Carinthian throne saw the rise of former Miruvian noble, Baron Stefan Uros raise an armed force to reclaim the throne. In the ensuing War of Carinthian Succession, the King Petar IV, backed by Vespasian mercenaries secured the throne for Prince Mislav, with Stefan Uros killed at the Battle of Plavno. The Novalian-backed victory led to the establishment of the centuries-long alliance between the Carinthian and Novalian crowns, who would regularly combine forces in confronting Miruvian activity or revolts.

In the 1580s, Povelia at the behest of Pope Gregorius VIII succeeded in establishing a military alliance with Duchy of Chiastre and the Grand Duchy of Faulia, with volunteers from the central and southern Vespasian states, and dispatched the combined force of 35,000 men under the command of Aurelio Guiliano Diodato to northern Euclea to support the Catholic states in the Amendist Wars. By, the end of the conflict, over 14,000 Etrurians had died, yet the war would prove pivotal in the establishment of Povelian-led leagues capable of intervening in northern Euclean affairs. The religious upheaval of the late 16th and early 17th centuries saw the tightening of the relationship between the Etrurian states and the Papacy, with the former being among the most proactive and prolific in the pursuit and destruction of Amendist movements. One of the most iconic events in Etruria during the reformation, was the capture and Execution of the Ten Confederati. The ten priests from Faulia were accused of heresy and burnt at the stake on April 14 1585 by order of Duke Amadeo IV. The Amendist conflicts had the further consequence of elevating Povelia into an Euclean power, which would lead directly to the disasterous involvement of Povelia and her allies in the Ten Years' War. Fearing an empowered Gaullica, as well as a religious view that Estmere and the Rudolphine Confederation were confronting an Amendist and Episemalist invasion of Catholic Euclea, Povelia established a league of supportive Etrurian states entered the conflict against Sunrosia, Gaullica and Narozalica. Despite early victories under Giovanni di Bessa, the Povelian League was soon encountered major setbacks and heavy losses to Gaullican armies. The League army deployed to fight in Werania was utterly destroyed at the Battle of Veichtach. By late 1719, the Povelian League began to collapse, with Altidona, Dinara and Carvagna withdrawing their forces, leaving Povelia and Torrazza alone to continue fighting. The war came to an end in 1721, with Povelia, Estmere and the Confederation subjected to a humiliating defeat, with Povelia cedeing Belmonte to Gaullica. The costs of the conflict for Povelia proved destabilising as much as devastating, within months of the war's end, pro-independence revolts erupted in Valorea, without support from colonial forces in Belmonte and the shortage of manpower in Povelia, the colony secured independence in wake of a short and relatively bloodless war of independence. Povelian authorities in Novo Poveja were successful in stamping out attempts to similar revolts, though these efforts would only serve to radicalise other elements of Novo Povejan society.

From 1721 onward, Povelia began its steady decline as a great power, a decline that inticed the Principality of Tyrrenhus to act on its long-held ambition of supplanting Povelia as the dominant Etrurian state. In 1757, Tyrrenhus launched its invasion of Carvagna, sparking the Central Etrurian Wars. The war would see further irrepable losses inflicted upon Povelia and the northern states, while Tyrrenhus' successes saw a dramatic expansion in territory, the financial costs and disruption to food production would be key direct causes for the Etrurian Revolution.

Revolutionary Etruria (1790–1810)

The Tyrrenhian Wars (1730-1775), were a series of small and short to large and extended conflicts between the Principality of Tyrrenhus and primarily the Exalted Republic of Povelia, albeit with the latter occasionally supported by northern Vespasian states. The wars were caused by the long-held ambition of the Tyrrenhian Grand Princes to unite Vespasia and proclaim themselves King. The conflicts from their outbreak in 1730 until the 1770s had limited effect on the fabric or economic system of the Vespasian states. However, the Eighth Tyrrenhian War (1771-1775) caused a complete rupture in the social and economic fabric of the Vespasian states. After a series of lightning and devastating victories, Tyrrenhus annexed the duchies of Carvagna and Torrazza, while seizing vast territories from Povelia. Despite the victory, the loss of life coupled with the labour shortage crippled food production across Vespasia. This brought Tyrrenhus to the brink of bankruptcy, forcing Grand Prince Alessandro III to increase taxation, hitting the peasantry and urbanised artisanal and merchant classes particularly hard.

Between 1775 and 1782, the draconian taxes and the violent repression of the numerous peasant revolts were supported by the nominally powerless Tyrrenhian Senate. In the summer and autumn of 1781, the effects of the taxes on the rural poor were felt, when cash crops seized failed to deliver any meaningful improvement to the state treasury, while the amount seized sent food prices skyrocketing, sparking bread riots across the Principality. In early November 1782, the impotent Senate published a proposal law denouncing the taxes and urging for a tightening of Royal expenditure. In response, Grand Prince Alessandro III shuttered the Senate, leading to opposition senators forming the Aventine Senate, to demand a constitutional monarchy. The Grand Prince’s arrest warrants for its members sent them into hiding, while some went into exile in other parts of Etruria. In the summer of 1783, the Principality abolished the War Widow’s Exemption, forcing widowed women back into the tax system. The subsequent March of the Widows and the Mothers’ Massacre unleashed revolutionary uprisings, leading to the overthrow of Alessandro III and the return of the Aventine Senate in November 1783. In January 1784, Alessandro III and his family were executed, and a Republic was proclaimed on January 20.

The new Republic fell under the rule of the Aventine Triad, comprised of the leaders of the left-wing radicals, constitutional moderates and religious republicans. Factional tensions, especially between the anti-religion left and proto-theocratic republics rapidly grew. From the proclamation until July, Tyrrenhian cities became battlegrounds between the Scugnizzi (radical left) and Pantheonisti (religious republicans). In June, an alliance of Vespasian states with the support of the Kingdom of Carinthia and Kingdom of Novalia declared war on the fledgling republic, while the Scugnizzi’s plan to persecute and remove the Catholic Church provoked a coup by the Pantheonisti, which was followed by La Tempesta, the mass killing of its factional enemies, perceived counter-revolutionaries and enemies of the Republic. With control over the Republic’s political power centres, the Pantheonisti proclaimed the Republic of Heaven on July 30, 1784 and issued the call for a Giusto Ospite or mass mobilisation, while also announcing its plan to “extend the boundaries of the Republic to all Etruria as the Solarian Republic once stood.”

From 1784 until 1787, the Republic of Heaven rapidly defeated its Etrurian enemies, uniting the Vespasian states for the first time since the Solarian Empire, while its defeat of Novalia and Carinthia in 1788 saw them annexed into the new Etrurian Republic. This resulted in the independence of Povelia’s remaining colonial possessions. In 1789, the Republic annexed the Ecclesiastical State in hope of gaining the support of the Pope through force. This led to the Flight to Verlois, where the Papacy would be based until XXXX. The seizure of Solaria provoked a response from the Kingdom of Gaullica, which sought to contain the newly united Etruria, expanding the Etrurian Revolutionary Wars across most of southern Euclea, these wars coincided with the Weranian Revolutionary Wars and established the alliance between Etruria and the Weranian Republic. The wars only served to further radicalise the Etrurian revolution, with La Tempesta reaching its violent peak in 1790. In the process of consolidating the Republic of Heaven, thousands would be killed across Etruria, while hundreds of thousands of Episemalists were either killed or forced to convert to Catholicism. The revolution also saw the introduction of equal rights between men and women in accordance to the interpretation of Galatians 3:28. The Republic also seized all land under its control in accordance to Leviticus 25:23 and proclaimed all property to be common ownership in according to Acts 2:44-45. The Republic also abolished the slave trade and actively sought to destroy the trade routes in the Solarian Sea.

Despite historic victories such as the Battle of Sofuentes, Battle of Castiliscar and the Battle of Montmaurin, the Republic could not maintain its war effort indefinitely. The costs of conflict, the violent excesses of La Tempesta coupled with growing disenfranchisement with Pantheonismo soon led to the widespread clamour for the restoration of monarchy. On the 12 August 1810, the Republic of Heaven was overthrown by pro-monarchist senators and army units, resulting in the Caltrini Restoration. The newly formed United Kingdom of Etruria maintained rule over the Vespasian states, Carinthia and Novalia and secured peace with its Euclean neighbours, albeit with great restrictions on its military and foreign policy. The restoration also saw the monarchy accept much of the republican notions, creating one of the first constitutional monarchies in Euclea.

Royal Restoration and 19th century (1810–1888)

Followign the royal restoration in 1810, the newly formed United Kingdom of Etruria emerged as a rising Euclean great power. Under the reign of Caio Aurelio I, the kingdom was successfully consolidated and one of the first constitutional monarchies emerged. The royal household was keen to protect its power from any resurgence of republicanism and as a result purused a two-pronged strategy - maintaining constitutionalism and uniting the country through imperialism and colonialism. This strategy began in earnest with the annexation of Emessa in 1814 as part of the Kingdom's operations against piracy. This was followed by the acquisition of several treaty ports in modern-day Zorasan and Subarna. Between 1810 and 1830, the relationship between the Vespasian, Carinthians and Novalians was redefined and made more equal, further aiding the monarchy in consolidating its rule and Etruria as a great colonial power.

In 1847, the Kingdom's constitution was amended by Caio Eugenio II, which dramatically expanded the basic rights and freedoms of the state, but electoral laws continued to exclude the non-propertied and uneducated classes from voting. These reforms resulted in the rising domination of liberal forces. This was followed by a resurgence in Etrurian contributions to science and technological discovery. Industrialisation in the south and central regions of the country left the rural north underdeveloped and overpopulated, resulting in decades of construction and engineering to expand industrialisation to the larger cities of the north. This uneven industrialisation led to the rise of the Etrurian Socialist Party, which would come to challenge the conservative-liberal tradition from strongholds in the north.

Starting from the last four decades of the 19th century, Etruria developed into a colonial power by forcing under its rule on vast swathes of northern Coius. Successive Etruro-Pardarian Wars saw the annexation of the Gorsanid Empire by 1860. This was followed by the annexation of territories in Satria, in 1863, Etruria's colonial possessesion were reformed, establishing Satria Etruriana, Satria Libera, Cyrcana, Bahia Etruriana with colonial protectorates over the Pardaran and Ninavina. Colonial tensions with Estmere resulted in the Etruro-Estmerish Wars and the development of the Royal Etrurian Navy into one of the most advanced and largest of the Euclean powers. The period between 1850 and 1880 marked the zenith of the United Kingdom, being marked by territorial expansion, socio-political and cultural modernisation of Etruria and its society.

In 1882, Caio Augustino ascended to the throne aged 17, falling rapildy under the influence and control of Prime Minister Girolamo Galba. Galba's control over the monarch was so profound that when the Senate sought to curtail the prime minister's power, he had the senate dissolved on three occassions, sparking elections that further entrenched Galba's power. Popular opposition to Galba grew between 1884 and 1886, which was deepened due to chronic shortages of capital and an emerging debt crisis. Galba responded with heavy handed tactics using royal ascent, in turn souring the once close relationship between monarchy and subject. In 1887, the anti-Galba movement fell under the leadership of Cardinal Romolo Caio Alessandri, a popular and high-ranking Etrurian cardinal, and Pantheonista. In 1888, this opposition erupted into the San Sepulchro Revolution following the arrest and death of three elder Senators, blamed on Galba. In the ensuing chaos, Galba fled Etruria for neighboring Gaullica, while under pressure from his family and facing threats of regicide from the revolutionaries, King Caio Augistino abdicated. Cardinal Alessandri was proclaimed interim Chief of State (Capo di Stato). This marked the end of monarchy in Etruria and the establishment of the Etrurian Second Republic.

Second Republic (1888–1937)

Following the establishment of the Etrurian Second Republic under Cardinal Romolo Alessandri, Etruria rapidly began to reform toward establishing a wider democracy and civil liberties. Between 1888 and 1900, male suffrage was repeatedly expanded while new laws guaranteeing the freedom of speech, thought and religion were passed. The new democracy established a “federal-union” of three constituent states, granting equal power and representation to the three peoples of Etruria. This new political freedom enabled the rise of organised trade unionism and the political left. In 1899, Cardinal Alessandri died, sparking a general election that saw the victory of the National Liberal Union under Alfredo Di Rienzo. The new government fostered further expansions of male suffrage, before ultimately introducing universal male suffrage for those aged 21 and above in 1902. This was followed by economic reforms that led to significant growth and modernisation.

The 1910s would see repeated crises in the colonies, with the Khordad Rebellion in Pardaran from 1912. These colonial uprisings played a significant role in a sense of “systemic failure” which was exacberated by the Great Collapse, which sparked a global economic recession. The economic crisis led to a rise and increasing militancy among the Etrurian left-wing parties, specifically the Etrurian Section of the Worker’s Internationale. The rise of the Liberal Republics in the 1916 election under Alessandro Luzzani saw major economic reforms and crackdowns on the far left, culminating in 1924 Schiatarella Crackdown that destroyed the ESWI. This had the effect of leaving the far-right as the only alternative to the liberal-conservative tradition.

The 1920s was dominated by rising global tensions, led by the rise of functionalist Gaullica. The same period saw significant divisions within Etruria between functionalist movements and those who opposed the totalitarian ideology. So profound was the division in Etruria, that the government was forced to purge the armed forces of pro-Gaullican officers from the mainland to colonial postings. Etruria, nominally allied with Estmere and Werania in the Grand Alliance failed to enter the war in 1927 owing to its ideological split. However, following the removal of pro-Gaullican figures from power and influence and a series of promises for territorial expansion, Etruria entered the Great War in 1928. The country gave a fundamental contribution to the victory of the conflict as one of the "Big Three" top Allied powers. The war was initially inconclusive, as the Etrurian army got stuck in a long attrition war in the Aventines, making little progress and suffering very heavy losses. Etruria saw greater success against Amathia and Piraea in the west and in halting the Gaullican advance in Florena. In Coius, Etruria’s colonies initially came under immense pressure and facing the threat of being evicted from its colonies, the Etrurian army was reorganised. Leadership changes and the mass conscription of all males turning 18 led to more effective Etrurian operations and victories in key major battles. The Etrurian Navy re-established dominance over the Solarian Sea, enabling the mass deployment of forces to the colonies. Eventually, in December 1934, the Etrurians launched a massive offensive against Gaullica, culminating in the victory of Vittorio Rivodutri. The Etrurian victory marked the end of the war on the Aventine Front, while smaller engagements saw Etruria push Gaullica out of Florena. Combined these victories proved instrumental in ending the war three months later.

During the war, more than 680,000 Etrurian soldiers and civilians died, leaving the country on the verge of bankruptcy and famine. The failure by the victorious allies to award most of Etruria’s promised territories led to a significant rupture in the political stability of the Etrurian government. Nationalists, many of whom were pro-Gaullican prior to the Great War returned home to agitate against the government. This led to the emergence of the Great Betrayal theory. The war also saw a resurgence in the far left, leading to political violence across the country.

National Solarian period (1937-1946)

As the post-war situation worsened, the far-right which boasted significant support among the military, most of whom feared a far-left revolution owing to economic crisis, began to plot against the republic. In late 1936, an Emergency Government for Peace was established with President Marco Antonio Ercolani remaining as a figurehead. This military government slowly eroded institutions and played a pivotal role in the Legionary Reaction of 1937, in which the Revolutionary Legion of Etruria assumed power under the co-leaders of Ettore Caviglia and Aldo Aurelio Tassinari. The Second Republic was replaced with the single-party totalitarian Solarian Republic of Etruria. Between 1937 and 1943, the SRE focused entirely on rebuilding the economy and Etruria’s military might. The National Solarian regime also restored control over the country’s colonial possessions while rallying the people for conflict in order to “avenge the great betrayal” and to seize territories promised to Etruria. The same period saw violent repressions of political opposition and criticism, as well as the Etrurianisation of Tarpeia and Emessa.

In 1943, the Solarian War broke out with Etruria’s invasion of Piraea, followed by attacks on colonial mandates in Tsabara, Satria, and later invasions of neighboring XX to the east. The war saw Etruria face a coalition under the leadership of the Community of Nations, which steadily overwhelmed and defeated Etruria in Coius. In 1946, with Gaullica’s entry in the war against Etruria, the country itself came under direct attack. The invasion of Etruria proper led to the collapse of the SRE with the overthrow of the regime by popular revolt. Etruria unconditionally surrendered on May 16 1946.

The Solarian War left over 500,000 Etrurian soldiers and as many civilians dead, Etruria saw the total loss of its colonial possessions who were granted independence by the CoN and the Etrurian economy had been all but destroyed; per capita income in 1946 was at its lowest point since the beginning of the 20th century. The war also saw numerous atrocities committed by Etruria against occupied territories, including the Piraean Genocide. The National Solarian regime was succeeded by a Community of Nations led provisional government who oversaw the restoration of democracy and the rise of the Etrurian Third Republic.

CN Mandate and Third Republic (1946-1960)

Following the unconditional surrender of Etruria in 1946, as per the Treaty of Ashcombe, the country fell under the administration of a technocratic government headed by the Community of Nations diplomat Seán Fitzgerald. The task of the Community of Nations Mandate for Etruria (CNME) was to oversee reconstruction and the restoration of democracy. The CNME was tasked further with developing a system of government that would harden the democratic system from seizure by extremist parties. The CNME’s economic policies prove poor in modernising and rebuilding Etrurian industry, while organised crime groups, especially the Etrurian mafia came to dominate many industries, while many newly formed companies fell under the corrupt influence of politicians. Corruption flourished, coupled with a weak currency, shortages of goods and the indifference of the major powers assured Etruria’s failure to recover by any substantial measure by 1948. The constitution introduced by the CNME in collaboration with Etrurian politicians was fundamentally flawed and would result in revolving door governments, while its vague references to the civil service was swiftly abused to see the return of a spoils system, further weakening the central government’s ability to oversee and manage reconstruction. The constitution constructed a substantially weaker central government, empowering the states. This in turn had the effect of resurrecting regionalism and in some states, a new nationalism around the pre-revolutionary states and statelets. The focus on industrial cities unleashed a wave of Veratian nationalism, which at this time remained predominately rural.

In 1948, Democratic Action under Giuseppe Zappella won a majority in the Etrurian senate. The new government failed to confront the economic problems, shortages and bottlenecks and after two years collapsed owing to widespread bribery among cabinet ministers. He was succeeded by Mauro Vittore Camillo, whose economic policies though an improvement on Zappella involved the mass printing of money to fund reconstruction. Most of this capital would find itself embezzled or seized by the mafia through falsified contracts or front projects, while in turn annual inflation skyrocketed. The federal government was soon rapidly descending into chaos with a distinctly conservative judicial branch blocking many of Mauro’s policies and laws. The social and moral decay that followed the Solarian War only worsened during the 1950s, with petty criminality surging in the cities and a decline in Etrurian cultural output.

The reconstruction that did occur came to be focused on established industrial cities, in southern and northern Vespasia, while Carinthia and Novalia languished in destitution and ruin. The decision by the Democratic Action government to pursue heavy industry to fund rural reconstruction decimated the predominately rural states of the federation. In both Carinthia and Novalia, the devastation and poverty gave space to the far-left and separatist-nationalist movements and parties. The far-left saw support both materiel and political support from the Amathian Democratic People’s Republic and Swetania. Initially these new nationalist movements aimed to secure power in their respective states and then to present independence referendums. However, these groups found that while support was growing, it was only “skin deep” according to historians, as in many voters saw voting for nationalist parties as a means of protesting against the lack of economic reconstruction.

In 1952, the Novalian People’s Liberation Front was formed out of a grouping of Solarian War veterans. The NPLF attracted the attention of the socialist bloc in Euclea and was provided safe havens in Piraea and Amathia. The election of the centre-left Democratic Worker’s Party under President Ferdinando Grillo in 1953 did little to stem the growth of nationalism in Carinthia and Novalia. The same year, the various left-wing nationalist groups in Carinthia united to form the Combatant Front for Carinthian Liberation. In response, numerous pro-Etrurian nationalist movements rose up in response, including the Black Unionists and the National Volunteer Defence Front, by the end of the year both sides were clashing in running street battles across Carinthia and Novalia. In 1953, state elections in Novalia saw the Farmers and Workers Union led pro-Etrurian alliance win most seats in the state legislature, pushing the Novalian nationalists toward armed insurrection over democratic means of securing independence. That year, the NPLF attacked six police stations and army bases, distributing weapons and munitions to supporters. Similar actions took place in Carinthia, sparking the Western Emergency.

From 1953 until 1960, the nationalist armed groups would limit their attacks and operations, often just retaliating against unionist groups such as the NVDF. The violence further limited the degree of reconstruction and economic progress in both states, while the violence undermined the DWP government in Povelia. The violence, the wider sense of declinism among Etrurians, the stagnant economy and rampant corruption also provided a vital space for the resurgence of far-right politics at the national level. In the 1958 election, the New Republic Movement, a neo-functionalist party that advocated military action against the growing nationalist threat won over 35 seats. The inability by the central government to face the escalating violence in the west and the further refusal to call out foreign support drove many senior figures within the Etrurian armed forces to begin planning a seizure of power to protect national unity. On February 19 1959, the NPLF bombed the railroad connecting Vilanja to Drostar, causing a train to derail and leaving over 100 people dead. The next day, the Etrurian Armed Forces began to deploy forces without government permission, the subsequent political struggle saw the government acquiesce, empowering the generals who stepped up plans for a seizure of power.

This coup took place on the 4 May 1960 and saw a bloodless and peaceful transfer of power from President Massimo Bartolucci to General Francesco Augusto Sciarri who assumed the title of Chief of State (Capo di Stato) and swiftly established a military government.

Military dictatorship (1960-1983)

Following the bloodless coup in 1960, the new military government Chief of State Sciarri declared its intention to transform the Etrurian government into a “fully functioning national security state.” Overnight, the military closed the Senate and disbanded the state legislatures, replacing the democratically elected Prefects with two co-governor positions, one being a civilian and the other a military official. The 1948 Constitution was abolished, stripping all Etrurians of their civil liberties and freedoms. Over the course of 1960, the Government for National Unity and Security shuttered hundreds of newspapers, radio and television outlets and established the Special State Security Organisation (SSSO) to pursue the left-wing nationalists and critics of the military regime. During its 24-year rule, the military would disappear over 8,000 people, while only 1,582 people are recorded to have died as a result of government action. Many NGOs and pressure groups since 1984 have claimed that the death toll from the regime’s draconian national security laws and actions may exceed 10,000. Up to 24,000 people were killed in the Western Emergency, between 1953 and 1973.

To further consolidate the government’s position, it launched a series of military actions against neighbouring Piraea. The first saw the Apocorona Islands seized by Etrurian marines and paratroopers during Operation Serenità. This was followed six months later by Operation Lexicon that resulted in the disputed regions of Tarpiea also seized and incorporated into Etruria, to little to no condemnation or protest from the Euclean powers. The military regime justified its two invasions as “key to confronting the radical leftist separatism” in its western regions. The regime also stepped up its military deployments to combat the nationalists. The military also co-opted many of the pro-Etrurian militias and groups in Carinthia and Novalia to assist the armed forces, this would result in numerous cases of grievous human rights violations and massacres. The Etrurian military also would regularly cross the border into Piraea to conduct raids on insurgent camps. Together with the lack of overwhelming support among their own respective peoples, the nationalists began to lose ground by the mid to late 1960s. In retaliation for many setbacks, the left-wing nationalist groups would stage attacks in the Vespasian states, aided by Vespasian left-wing groups opposing the military government. In 1966, 22 people were killed in the Piazza Caciarelli bombing, 92 were killed in the 1967 Piazza della Vergine Maria bombing and 111 were killed in the 1969 San Alessandro Train Station bombing. These bombings entrenched popular opposition to the separatists and emboldened the military regime to step up its draconian measures against the separatists. By 1972, the crisis had come to an end with the collapse of separatism and the surrender of senior leaders. The Western Emergency was declared over in 1973, which would prove a high mark in support for the military government.

While the regime focused on destroying the separatist threat and maintaining Etrurian territorial integrity, it instituted a series of economic reforms led by financial experts and economists, who together formed the National Institute for Economic Reconstruction (INRE). The INRE was granted extraordinary powers by the military to seize property, businesses and land for purposes geared entirely toward promoting economic and wage growth. The military also launched a series of anti-corruption and mafia drives that proved somewhat successful at expelling waste, misappropriation and organised crime from the economy. However, it was later discovered that the military had relied upon several mafia groups for financing and its own corrupt practices. Aided by a cheap currency and low wages, the military backed INRE’s policy of sponsoring manufacturing industries, which by 1984 had turned Etruria into one of the fastest growing export economies. However, INRE and the military’s pro-statist approach to economics failed to deliver the rocket-speed growth necessary to see the two-decade gap between Etruria and its neighbours closed. One area of success what the government’s ability to secure investment from Euclean governments, regularly achieving such by warning that economic collapse would see Etruria fall to socialism.

By the mid-1970s, the victory over the separatists and the improvements to Etruria’s economic wellbeing resulted in the military government achieving a high watermark for popularity. The military’s use of extensive Etrurian nationalist propaganda campaigns would further fuel the resurgence and resilience of the country’s far-right. Many Etrurians were willing to forego their civil liberties for security and prosperity. However, by 1976 much of Etrurian society viewed the defeat of the far-left separatists as a mission accomplished for the military government and the adoration soured. In 1977, students protested censorship and were met with live gunfire by military police, which soon escalated into a nationwide protest, in a major concession, Chief of State Gennaro Aurelio Altieri announced his intention to lead negotiations with civil society groups for the eventual restoration of democracy. In 1983, the military and the United Committee for Democracy secured an agreement for the restoration of democracy. While the military would step down peacefully and withdraw from politics, the UCD conceded to the military, legal immunity for all regime officials and leaders. The future democratic system would retain the military’s ban on political parties or societies dedicated to promoting non-Etrurian nationalisms and the right for the security services to shutter media outlets, groups or societies promoting the same.

On the 1 July 1984, Etruria held its first democratic election since 1958. The centre-left Social Democratic Party under Miloš Vidović, the first Novalian to serve as President, won the largest share of seats and entered into coalition government with Sotirian Democracy.

Contemporary (1983-present)

The return of democracy in 1983 was followed by widespread economic and social reforms led by President XX. The 1983 Constitution proved highly versatile in comparison to the 1946 constitution, delivering Etruria strong and capable coalition governments. By 1990, Etruria had returned as one of the largest industrial economies in the world and in Euclea. In 1991, XX was defeated by Enrico Biava of the centre-right Federalist Party, who entered into coalition with the Sotirian Democratic Party. The Biava government continued the neo-liberal reforms of the centre-left government under XX, seeing Etruria achieve significant improvements to living standards and per capita incomes.

In 1996, however, a group of investigative journalists published the Capo del Leone Scandal, in which it was discovered both parties had engaged in a highly lucrative embezzlement plot involving the new town of Capo del Leone. The ensuing fallout forced the resignation of Biava and a restructuring the major parties. In the subsequent election, the Sotiran Democratic Party won the election, entering the government alongside the Workers and Farmers Union under Marko Stepanovic. Strident anti-corruption laws were introduced and public confidence in the political system was relatively restored by 2003.

The 2005 Global Recession hit Etruria hard, forcing the country into facing 23 months of recession. Much of the economic progress made in the 1990s was lost and many commentators argued that the situation was worsened by the corrupt practices of Etrurian companies, especially the banking system. The 2006 snap election saw the return of the Socialist Party under Urbano Onoforio, who instituted numerous reforms and stimulus packages. By 2007, Etruria had returned to strong economic growth, with manufacturing replacing services as the key driver of Etrurian economic output.

In 2011, Onoforio was defeated by Emiliano Reali and the Etrurian Federalist Party who entered into coalition with the Veritas party. This coalition led to a splinter group of the EFP forming into the Citizens’ Alliance. Invoking the closer relationship with the Euclean Community, Reali’s government announced plans in 2013, for a popular referendum on Etruria joining the bloc. This provoked a surge in support for right-wing populist parties, which united to form the Coalition of the Right alliance, led by National Action. Still requiring time to meet Euclean standards to achieve membership, the gap between announcing the referendum and holding the vote was extended to three years. During this time repeated corruption and personal scandals hit the Reali government, this would lead to the undermining of the government. In the 2016 referendum, the No-campaign defeated the government led-Yes campaign, stalling Etrurian membership of the bloc indefinitely.

Following the rejection of EC membership, the centre-right government collapsed in August, leading to the 2016 election, which saw a surprise landslide victory by the right-wing populist Tribune Movement, which entered government in coalition with the Workers and Farmers Union, with Francesco Carcaterra as president. Between 2016 and 2018, the Tribune Movement government instituted a series of reforms, including the restoration of capital punishment, federalising law enforcement, electoral reform and abolishing a series of government offices charged with securing EC membership. In 2018, during the EC-Etrurian Crisis, a snap election saw the Tribune Movement re-elected using its newly introduced electoral system, allowing the party to form the first ever single-party government since 1983. This was followed by Operation Gladio, which devastated organised crime and provoked a crisis over civil liberties. The government also passed legislation limiting debate over Etrurian war crimes during the Solarian War, increased federal control over universities and in 2020, effectively banned abortion.

Geography

Etruria is located in Southern Euclea. To the north, Etruria borders Gaullica which is dominated by the Aventine Mountaines which also encloses the Eugenian Plain to the east, which borders Florena. The Aventine Mountains are met in the north by the Etrurian Mountains which run through roughly centrally through the country to the south, flanked on both sides by wide plains, which however are marked by hilly regions, before dropping in altitude along the coasts. In the north are two major lakes, Lake Imperia and Lake Jovia. Etruria is also includes one large islands; Aeolia and numerous smaller islands.

The country's total area is 548,549 km² (211,796 sq mi). Including the islands, Etruria has a coastline of 2,636 kilometres (1,637 miles) on the Solarian and Mazdan seas.

The Aventine Mountains form Etruria's backbone and the Eturians form most of its northern and eastern boundary, Etruria's highest point is located on Monte Tinia (4,810 m or 15,780 ft) in the northern reaches of the range. The Volterra, Etruria's longest river (1,114 kilometres or 692 miles), flows from the Etrurians on the northern border with Guallica and crosses the Novalian plain on its way to the Solarian Sea. The five largest lakes are, in order of diminishing size: Imperia (1,000 km2 or 386 sq mi), Jovia (212.51 km2 or 82 sq mi), San Paolo (145.9 km2 or 56 sq mi), San Pietro (124.29 km2 or 48 sq mi) and Balestra (113.55 km2 or 44 sq mi).

The country is situated at the meeting point of the XXX Plate and the XXX Plate, leading to considerable seismic and volcanic activity. There are 17 volcanoes in Etruria, three of which are active: Vosca, Stalleria, Vesano and Veturius, which last erupted in 2015.

Because of the great longitudinal extension of the peninsula and the mostly mountainous internal conformation, the climate of Etruria is highly diverse. In most of the inland northern and central regions, the climate ranges from humid subtropical to humid continental and oceanic. In particular, the climate of the Eugenian Plain geographical region is mostly continental, with harsh winters and hot summers.

Climate and weather...

Government and politics

Etruria is a federal parliamentary republic governed under the 1983 Constitution, recently amended in 2017, which serves as the country's supreme legal document. Unlike other presidential republics the President is both head of state and head of government and depends for his tenure on the confidence of Parliament. It is a constitutional federal republic and representative democracy, in which "majority rule is tempered by minority rights protected by law".

Federalism in Etruria defines the power distribution between the federal government and the constituent states. The government abides by constitutional checks and balances, which however have never been considered overly strong. The Constitution of Etruria, which came into effect on 1 July 1983, states in its preamble that Etruria is "a sovereign, Solarian Catholic democratic republic and union of three states". Etruria's form of government, traditionally described as "quasi-federal" with a strong centre and weak constituent states, has grown increasingly federal since the late 1980s as a result of political agitation at the constituent level. However, since 2016, the level of separation between federal and state has significantly declined.

Branches of government

Executive: The President of Etruria is the head of state and head of government and is supported by the party or political alliance holding the majority of seats in the lower house of the senate. The executive branch of the Etrurian government consists of the president, the vice president, and the Federal Cabinet—this being the executive committee—headed by the president. The president is mandated to select his deputy and his Federal Cabinet, however the cabinet must receive the confidence of the state council to be confirmed. Any minister holding a portfolio must be a member of one of the houses of congress. In the Etrurian parliamentary system, the executive is subordinate to the legislature; the president and his council are directly responsible to the lower house of the congress (the chamber of representatives).

The president and the cabinet may be removed by the senate by a motion of no confidence. There are no term limits for the presidency.

|

|

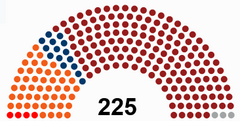

Government (194) Tribune Movement (194) People's Opposition (99) Citizens' Alliance (71) Workers and Farmers Union (14) Etrurian Greens (11) |

|

|

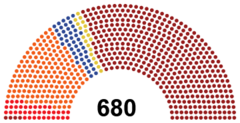

Government (414) Tribune Movement (414) People's Opposition (266) Citizens' Alliance (160) Democratic Alternative for Etruria (45) Etrurian Socialist Party (38) Workers and Farmers Union (19) Popular Renewal (4) |

Legislature: the legislative branch of Etruria is based on the adversarial model of parliament, as such the federal legislature is parliamentary. The Senate is split into two houses: the State Council and the Chamber of Representatives. The Chamber of Representatives is the lower house and is the more powerful. The State Council is the upper house and although it can vote to amend proposed laws, the chamber can only vote to overrule its amendments should the state council reject the bill more than twice. Although the State Council can introduce bills, most important laws are introduced in the Chamber – and most of those are introduced by the government, which schedules the vast majority of parliamentary time in the Chamber. Parliamentary time is essential for bills to be passed into law, because they must pass through a number of readings before becoming law. Prior to introducing a bill, the government may run a public consultation to solicit feedback from the public and businesses, and often may have already introduced and discussed the policy in the president's State of the Union address, or in an election manifesto or party platform.

The Chamber has 680 voting members, each representing a senatorial district for a four-year term without term limits. Chamber seats are apportioned on the basis of population, with Vespasia holding 480, Novalja holding 145 and Carinthia holding 55.