Haller Base

Haller Base

Haller-Basis | |

|---|---|

| Haller Base–Lunar Research Station | |

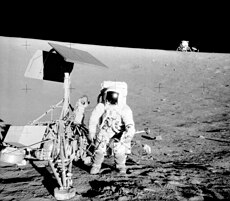

Haller Base facilities on the surface in 2008 | |

| Sovereign state | |

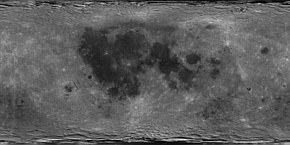

| Location on Luna | Jenssen E crater, Soguichi Plateau |

| Administered by | Lunar Exploration Initiative of the |

| Established | 9 November 1987 |

| Retired | 15 February 2009 |

| Named for | Emil G. Haller |

| Population (1987 / 2008) | |

| • Total | 3 / 6 |

| Type of operation | |

| • Crew | All year-round |

| Operation | |

| • Status | Inoperational |

| Dimensions |

|

| Facilities | 9 buildings and facilities List

|

Haller Base, officially the Haller Base–Lunar Research Station (Hesurian: Haller-Basis Lunare Forschungsstation), is a Mascyllary research station on the sloped rim of the Jenssen E crater in the Soguichi Plateau, on the surface of Luna, the second planet of the world's binary planet system. It was operated under the joint Lunar Exploration Initiative (MLEI) of the MAOA and Air Force from 1987 to 2009 and is considered to be the furthermost point of Mascyllary jurisdiction and only one on Luna. The base is named in honour of rocketry pioneer and polar explorer Emil Haller who was a significant contributor to the foundation of the MAOA and its early human spaceflight projects.

Haller Base is the first modular planetary station and first large man-made structure on Luna, and was assembled over the span of multiple subsequent manned missions from 1987 to 1999. The original base, less than a fifth of the completed station's volume and named Falkenhall, landed as part of the Sigma-Haller Expedition on 9 November 1987 by the space agencies of Mascylla and Dulebia at the end of the Sigma program. With the Haller 87 and Haller 88 missions, the base became the first continuously inhabited research station on Luna and still maintains the longest duration of continuous human presence in space at 4,018 days. Since, the station has hosted up to 82 astronauts, the largest number for any Lunar research station, and has repeatedly been partially rebuilt and expanded upon. By 2008, Haller Base encompassed five pressurized modules, and two unpressurized components, the H-5E Unpressurized Multipurpose Module and the power-supplying photovoltaic array on the surface.

The station was purposefully constructed and ultimately served as a research laboratory which enabled crews to conduct scientific experiments on human biology, microgravity and radiation physics, astronomy, meteorology and space physics, as well as study the effects of long-term stay in space on humans. While the base operations and crew were militaristic in nature, it allowed scientific endeavours such as international collaborations with other countries to access the station. Haller 87 sustained three crew members, but the station's population continued to grow through its operation, with a peak six crew members of Haller 2000 and later 04 simultaneously on the station. In service from 1987 to 2009, Haller Base continued human presence on Luna, before it was agreed upon by the MLEI to retire the station in February 2009 mainly due to its aging hardware, damages sustained by meteorological phenomena and regolith exposure. The station has since been unoccupied and plans to either repurpose it for another settlement or preserve it as a protected area have been put forward.

Structural history

Original base (1987–1989)

Inception and location

Concepts and proposals of a lunar base for human habitation have been brought forward by MAOA since its inception in the 1970s, due to technical and budgetory constraints. In 1981, during the Sigma program, the MLEI of MAOA and the Mascyllary Air Force conducted a feasibility study of a possible base; the results of the study reccommended a research station of modular design, and a gradual development build-up over the span of approximately 10 years, or more. Consequently, the lunar base concept could only be realized once the Sigma program had been concluded and the MAOA budget could be diverted into the new project, then named Project Antares (Projekt Antares).

By 1983, five possible locations of the future base had been mapped and investigated by the Lunar General Surveyor Orbiter (LGSO; Lunarer Allgemeiner Begutachtungsorbiter) robotic spacecraft in polar orbit, launched in 1977. These included, among others, X crater, X crater in Mare Ingensis, Palus Epidemiarum, the X Highlands, and Jenssen crater. A year later, MAOA ultimately chose the Jenssen E crater in visual sight of the Rupes Ejeva scarp mountain range due to its geology of scientific interest and well-fitted flat terrain for construction and operation, and therefore it was excluded as a potential landing site for the remaining Sigma missions until 1986. In 1984, the Juser 2 lander arrived at the future base site to confirm its potential, photograph its surroundings, and conduct tests on the lunar soil; its scientific data affirmed the stance that Jenssen E was the most promising candidate.

Construction and Sigma-Haller Expedition

The initial first component of the station, the pressurized Falkenhall Main Service Block (Hauptbetriebsblock; MSB) module and its adjacent solar arrays measuring 4,000 m2 of operable area, were manufactured at the Gräbler Spaceflight Center near Rothenau, Aldia, beginning in 1982. The name Falkenhall was ultimately chosen by MAOA in reference to the oldest continuously inhabited urban settlement in modern-day Mascylla, having been founded by 600 BC. The modules were delivered on ship to the Spacecraft Processing Facility and Main Flight Operations Building at Cape Weimud Space Center in Akawhk in August of 1987 for final inspections, processing and preparation for launch. The module was designed with three docking ports suitable for berthing operations, three autonomous arrays of solar cells measuring 4.5 by 1.3 meters (14.7 by 4.3 feet) mounted on its roof, six nickel-cadmium batteries with a capacity of 4 kilowatts of power, ten externally mounted fuel tanks holding 8.8 tonnes of propellant, and is outfitted with early communications and control equipment. Falkenhall has a dry mass of 21,492 kilograms (47,382 lb), is 8.2 meters (26.9 ft) long and 4.1 (13.5 ft) meters wide.

Falkenhall was launched on 6 November 1987 on a purpose-built and modified version of the Atlant-3 rocket from Cape Weimud in Akawhk; the mission was incorporated into the Sigma program as the Sigma-Haller Expedition, crewed by a joint Dulebian-Mascyllary crew of Mission Commander Janus Heine. After the initial launch and the first two stage separations, the payload ascended to a 500 km (311 mi) high parking orbit. Eight hours later, the crew of the Sigma-Haller Expedition was launched to the cargo stage waiting in orbit on an Atlant-4G, and performed a subsequent space rendezvous. The spacecraft complex was manned for re-configuration and trans-lunar flight preparations before firing the CSM third upper stage for trans-lunar injection on 7 November.

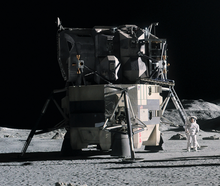

On 9 November, the two-stage Falkenhall module and its cargo load, referred to as LM-13 Dnepr, separated from the Sigma Command and Service Module (Kommando- und Betriebsmodul; CSM) Antares, having ferried it to lunar orbit, and descended to Luna's surface; Dnepr touched down at the ridges of Jenssen E crater of the Soguichi Plateau at 05:22 UTC. The three astronauts of the resident crew stayed on the newly established lunar base before returning to the CSM in low orbit; the base module served as the launch pad for the ascent stage, similar in operation to the Sigma Lunar Module (Lunarmodul; LM), which then docked with CSM-98 Antares again and was subsequently discarded. After 6 days of stay and the 4 days of travel following the trans-Aurorum injection, the crew of the Sigma-Haller Expedition returned to Aurorum on 18 November.

Complications and modification

The ascent stage of Dnepr inadvertently polluted the photovoltaic arrays with whirled up lunar regolith, which caused Falkenhall to suffer a blackout one day after Sigma-Haller's departure. Contact to the automatic systems of the station remained severed until the Haller 87 Expedition was able to clean and re-orientate the solar arrays while moving them 700 meters (2,297 feet) away from the designated but improvised landing and take-off site, two weeks later in December of 1987.

During the Haller 88 Expedition in July of 1988, a repurposed descent propulsion system (DPS) similarly used in the LM descent stage was utilized to blow away possibly hazardous or inhibiting regolith from the designated site and heat the material to fuse it into a durable and hardened platform. After installing edge and status lighting, LM-17 Heiserer of the Haller 89 Expedition was the first to land on the Sahalinov Landing Site (Sahalinow-Landungsplatz; SLS); in 1994, a second SLS including seven additional external fuel storage tanks were constructed 30 meters (98.4 ft) away from the first SLS.

Added modules (1989–1999)

Assembly

The construction of Haller Base was a major and ultimately multi-national undertaking in space and lunar architecture. The initial assembly began in November 1988 during the Haller 89 Expedition when two Base Node Module Adapters (Basisknotenmoduladapter; BNMAs) were attached to the passive Falkenhall module by two astronauts performing extra-vehicular activities, serving as nodes for future additions. Over the course of Haller Base's assembly, astronauts used some 1,100 hours of EVA operations as well as the Mobile Servicing Robotic Unit (Mobiles Betriebsrobotikeinheit; MSRU) as the base expanded in size and complexity. Similarly, since the Haller 92 Expedition, Haller Base was serviced and supplied by an evolved and heavy-payload five-astronaut version of the 1980s Sigma LM, the Lunar Surface Access Module (Lunares Modul für Oberflächenerkundung; LSAM); because the first active LSAM was LM-19 Fischadler, it is sometimes referred to as Fischadler (meaning "Osprey") by itself.

Elements

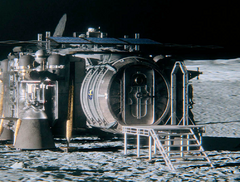

On 30 July 1989, the H-2B Crew Compartment and Science Module (Truppenabteil und Wissenschaftsmodul; CCSM) was launched into orbit and then delivered to Luna via the Haller 90 Expedition. The H-2B–Sagittarius vehicle performed the descent and docking to the Falkenhall-BNMA complex part-automatically and part-manually. Serving as the new operational centre of Haller Base, the H-2B module's computer system autonomously assumed control over the base from Falkenhall's systems, and was equipped with designated crew and sleeping quarters, a kitchen, multiple toilets and sanitary systems, and exercise equipment. Additionally, the scientific compartment of the large cylindric module, measuring 13.3 meters (43.6 ft) in diameter, supplemented the Falkenhall life-support systems with CO2 scrubbers, dehumidifiers, wastewater treatment systems, and oxygen generators. It also comprises the central command and operations room of the base. Mission Commander Felix Ahrndt later recalled the happiness and gratitude of subsequent Haller Expedition astronauts who stayed in the base before the expansions in 2011, commenting: "By this point Falkenhall was, well, "overcrowded" would be an understatement. It was like a tan of sardines, speaking from experience and talking to other Haller astronauts, and everyone talked about how happy they were that they now could take more than eight steps in any direction. H-2B was like a cathedral in comparison to the old Falkenhall lady." In 1991, H-2B was officially renamed to Aufgang (meaning "Dawn").

Over the next four years, Haller Base continued to expand. During the 1990 Haller 91 Expedition, the H-3 Science Module (Wissenschaftsmodul) was delivered to Luna as the primary new facility for research payloads, scientific experiments and medical life-support operations. The 23.1-tonne (50,927 lb) heavy research and experimental laboratory is identical in layout and design to the H-2B Aufgang module and was permanently berthed to it on 3 June 1990, and has since been the location of active research on Haller Base, encompassing studies and experiments relating to medicine, biotechnology, materials science, and other fields of physics. Aufgang was used frequently by international teams of scientists and for scientific research contributions of participating states, most notably Lavaria and Dulebia, in the form of experiments and delivered technology.

In 1994, the Haller 94 Expedition contributed the Main Airlock Module (Hauptluftschleusenmodul; MAM) to the base, intended to relieve Falkenhall's forward airlock system of potentially damaging over-use; before the addition of the MAM, EVAs could only be performed through the forward door of the first module, and an almost fatal accident during the Haller 93 Expedition on 2 September 1993 involving astronaut Lukas Krausmann highlighted the frequently used airlock's strain. It provided the base's capability of EVA operations on the lunar surface and was attached to Haller Base inbetween the Aufgang and H-3 modules. In order to alleviate the issue of the rapidly deteriorating performance of airlocks due to regolith exposure, the airlock, being 4.2 meters (13.7 ft) in diameter and 7.9 meters (25.9 ft) long, comprises two separate passageways, one from which astronauts can exit the base, and a smaller hatch for equipment storage and to clean used EVA suits of regolith, as well as nitrogen to mitigate post-spacewalk decompression sickness.

Two additional BNMAs and a more compact version of the H-2B and H-3 modules serving as a central node for the newer Haller Base complex, the H-4 Utility Node Module (Nutzknotenmodul; UNM), were delivered on the Haller 96, 97 and 98 Expeditions. The UNM accommodates additional sleeping quarters and sanitary systems for astronauts, and more importantly, houses vital electrical power storage units, areas for cargo holds, and controls for the base's electronic system; the addition of the UNM was in response to the base's rapidly increasing power consumption and ineffective control of power-generating capabilities from Aufgang, as was the installation of another 980 m2 (10,549 sq ft) of photovoltaic arrays outside Haller Base in 1997. During the Haller 98 Expedition in 1998, Haller Base was outfitted with 197 plates of a composite secondary hull consisting of stainless steel, kevlar and aluminium alloy to protect it from micrometeoroids.

The final expansion of the base to this date, the H-5E Unpressurized Multipurpose Module (Druckloses Mehrzweckmodul; UMPM), was brought to Luna in March of 1999 by the Haller 2000 Expedition. The UMPM was vertically mounted on top of the zenith docking port of the H-4 UNM, requiring 18 separate EVAs over the span of 48 hours and two specialized aerial work platforms. Once completed, the UMPM raised the total height of Haller Base to 17 meters (55.8 ft), and was added with the scientific experiments and devices intended for the module in the Haller 2000 and 01 Expeditions: the Wilhelm G. Neumayer Astronomical Observatory (Astronomisches Observatorium Wilhelm G. Neumayer; WiGNAO), Atmospheric and Lunaological Research Observatory (Atmosphärisches und Lunaologisches Forschungsobservatorium; ALRO), Angular Cosmic Interferometer (Kosmisches Winkelinterferometer; ACI), Lunar Muon and Neutrino Detector Array (Lunares Myon- und Neutrinodetektorfeld; LUMONDA), and Lunar Magnetic Spectrometer (Lunares Magnetospektrometer; LMS).

WiGNAO is an astrophysical observatory equiped with an iliosar telescope, x-ray, extreme ultraviolet and Hα spectroheliographs, and a coronagraph intended for space weather prediction and x-ray astronomy; ALRO, also being an observatory, was used for observational astronomy, as well as imaging spectroscopy, energetic neutral atom imagery and mass spectrometry of Luna's surface and faint atmosphere. ACI observed the power spectrum, polarization and temperature anisotropies of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) to survey galaxy clusters, whereas LUMONDA was a high-energy neutrino observatory and the LMS magnetic spectrometer investigated antimatter amounts in cosmic rays.

Completed state (1999–present)

By February of 2009, Haller Base consisted of five pressurized and two unpressurized modules. Following the announcement of the program's retirement, the last resident crew onboard the base, the Haller 09 Expedition, celebrated its continuous operation and deactivated its life-support system upon the crew's departure on 15 February. The numerous scientific experiments in the UMPM continued to be used by scientists on Aurorum and relay research data for another four years, until the base's central computer was commanded to go on stand-by in 2013. While Haller Base has not been in activation ever since, as of 2022, the photovoltaic arrays and electronic systems are still considered to be fully operational if activity were to be resumed. However, in 2019, multiple micrometeoroids damaged the parabolic communications antennae on Aufgang's outer hull, thus impairing direct communication to and from Aurorum.

International cooperation

The Mascyllary Lunar Exploration Initiative included a formal provision, the Lunar Base Joint Use Intergovernmental Agreement (LBJUIA), which allowed members and citizens from interested countries (eight in total) to participate in crewed spaceflights to Haller Base and contribute scientific experiments or other payloads to regular Expeditions. However, the LBJUIA does not govern nor specify the legal foundations of the programme and the base itself, and because no other to-date convention of international law governing formal jurisdiction on Luna is in effect, Haller Base is de facto a stateless property on territory akin to international waters; simultaneously, it is generally accepted to be subject to Mascyllary legal jurisdiction (the only country to de jure govern territory outside Aurorum, but not exercise sovereignty), despite the lack of any formal convention or agreement.

Participating countries

Astronauts

Various Berean and Pamiran astronauts visited Haller Base over the course of the LBJUIA's existence and its operation, in order:

- Wladimir Selyov – during the 1987 Sigma-Haller Expedition

People's Republic of Dulebia

People's Republic of Dulebia - Balduíno Miranda – during the 1992 Haller 92 Expedition

Lavaria

Lavaria - Corin Côté – during the 1996 Haller 96 Expedition

Sarrac

Sarrac - Kirill Antonov – during the 1997 Haller 97 Expedition

Dulebia

Dulebia - Tuomo Mäkinen – during the 1998 Haller 98 Expedition

Valimia

Valimia - Estevão de Mascarenhas – during the 1999 Haller 99 Expedition

Lavaria

Lavaria - Radomil Borisov – during the 2000 Haller 2000 Expedition

Dulebia

Dulebia - Valquíria Costa – during the 2001 Haller 01 Expedition

Lavaria

Lavaria - Felix Kirchhöfer – during the 2002 Haller 02 Expedition

Temaria

Temaria - Lidiya Vinogradova – during the 2004 Haller 04 Expedition

Dulebia

Dulebia - Claudette Tremblay – during the 2005 Haller 05 Expedition

Sarrac

Sarrac - Deodato Araújo – during the 2008 Haller 08 Expedition

Lavaria

Lavaria

Operation

Expeditions typically stay for multiple months and in some cases for almost the duration of a full year in the base, thus isolating them for extended periods of time. This has presented researched and reported dangers to crew health and inter-personal relations, among other stresses of physical and psychological nature. During the Expeditions, Haller Base is completely self-sufficient through extensive storage of food, water, and the autonomous solar power supply; during lunar nights, a system of batteries supports power consumption while a 2002-installed small-scale radioisotope thermoelectric generator is intended for emergency use in the case of a blackout. When crews are not present, ground control as well as automated central computer systems located in the H-2B CCSM oversee basic utilities and operations in the base.

Crew stay

The station was originally supposed to remain in operation for a total of ten years, but instead operated for almost twice the intended span. As a result, the older components of Haller Base, most notably the Falkenhall module, were often compared to a cramped and visibly used-looking "labyrinth" with exposed technical equipment and hoses, as well as crowded with cargo; the modules added in the later development of the base were considerably more modern and new, as had been pointed out by crew members.

The operation of Haller Base was subject to a stringent timetable and schedule as provided by the ground operators. The time zone used in Haller Base was Eastern Berean Time (EBT; UTC+03:00). Due to the 3.5-day long lunar days and equally long lunar nights on the surface, certain measures were taken to re-create the temporal cycle as perceived on Aurorum, mainly for crew comfort and convenience, like covering windows during "night hours", dimming internal lighting, or adjusting light colour temperature. While the morning and mid-day were reserved for work, exercise to combat muscle atrophy and spaceflight osteopenia, and space food breaks, the evening could be used by crew members for recreational or other activities. Haller Base was supplied with a number of items to provide entertainment for astronauts in their spare time: books, films, a collection of pre-recorded music, and a guitar. Additionally, astronauts brought along their own personal belongings in a designated bag, which they stored in their crew quarters.

Astronauts stayed and slept in phonebox-sized soundproof booths, similar in appearance and style to bunk beds on board naval vessels. The crew quarters were equipped with secured trunks for personal belongings, shelves, reading lamps, laptops, and a small window; the actual bed could remain un-tethered and horizontal due to Luna's noteworthy gravity. Two designated galley areas are located next to the quarters, which are mostly located in the H-3 SM, as is the area for sanitary and hygienic utilities, including three space toilets and a shower. The galleys feature three food warmers similar to a microwave, two refrigerators, a locked safe for alcoholic beverages (such as cognac, vodka, and schnapps) only accessible to the Expedition Commander, and a water dispenser. Despite the fact that crumbly food can be safely eaten due to the lack of weightlessness, most foods eaten in the base do not create crumbs, as vacuum sealed, frozen, and freeze-dried packaged food could be stored for longer for the long durations of Expeditions. Nevertheless, it is custom for arriving astronauts to re-stock the base with fresh vegetables and fruits, as well as sweets.

Transportation and communication

The base has two landing areas for spacecraft, the Sahalinov Landing Sites (SLS; ICAO: ASLP), each 29.6 meters (97.1 feet) in diameter. Usually, these are reserved for the Expeditions' descent configurations of the LM from 1987 to 1992 and the heavy-version LSAM since 1992. In rare circumstances, parked vehicles might need to be removed or relocated to allow for resupply missions, automated cargo LSAMs, to land at Haller Base. Flights to and from the SLSs depend on the arrival and departures of the respective crews, but LSAMs have also been used to scout and explore nearby areas of interest surrounding the base, such was the case during the Haller 93, 96, 2000, and 05 Expeditions.

The SLS landing pads are connected to the base through multiple improvised 900-meter (2953-feet) long routes used as regolith roads, termed the Thomas L. Knopp Lunar Highway (TKLH; Lunare Autobahn–Thomas L. Knopp). Ground transportation of crew and cargo is made possible by the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV; Lunares Lauffahrzeug), in use since the original Sigma program. Concepts of replacing the LRV with a pressurized modular cabin vehicle for long-term stay were discarded due to budgetory and practical restraints.

Communication of Haller Base is provided by the MAOA's VDÜS-2 and 4 satellites, and the VSKS-11 satellite of the Ministry of Defence of the Realm; these allow a date-transfer rate of some 60 Mbit per second, as well as broadband internet and satellite phone telecommunications access. Moreover, they provide the data uplink for the scientific data, status requests, and ground-based computer commands. Communication of non-military or non-scientific nature, and on the lunar surface for EVA activities, has been provided by amateur ham radio in the H-2B CCSM's command room.

Expeditions

Accidents

The program witnessed multiple incidents and accidents of varying severity and degree. The most significant of which was the destruction of the ascent stage of LSAM-32 Entdecker and the loss of the Haller 03 Expedition crew, 21 seconds after departure lift-off, on April 9, 2003; other major accidents include the sudden depressurization of the Falkenhall module airlock and the near killing of Lukas Krausmann during the Haller 93 Expedition on 8 April, 1993; an abort-to-orbit of CSM-101 Nordstern while performing a lunar orbit insertion maneuver during the Haller 89 Expedition on November 25, 1988; as well as the RSLS abort of the Atlant-3 vehicle carrying the crew of the Haller 98 Expedition on the CWSC launch pad before lift-off on November 2, 1997.

Haller 93 Expedition (1993)

On September 2, 1993, astronaut Lukas Krausmann of the Haller 93 Expedition loaded scientific gear, video tape, and a camera into the airlock section of the Falkenhall MSB for a routine EVA spacewalk. As he underwhent the "camp-out" procedure of reducing nitrogen from his bloodstream to avoid decompression sickness, both in the low-pressure (4.3 psi; 30 kPa) spacesuit atmosphere almost purely of oxygen and after the EVA activity, the closed airlock suddenly depressurized uncontrolled which caused his suit pressure to drop from the reduced 10.2 psi (70 kPa) to below 0.1 psi (0.7 kPa). Krausmann attempted to find the cause of the decompression before he fell unconscious after 14 seconds due to hypoxia. Within 30 seconds, Expedition Specialist Charlotte Reichenbach, who was currently performing a spacewalk for a scientific experiment, entered the airlock from the outside and provided Krausmann with an emergency supply of oxygen to prevent asphyxiation. Reichenbach tried to repressurize the airlock after 1 minute, and even though the atmospheric pressure was still below 3.8 psi (26 kPa), she opened the inward hard hatch to the station and brought Krausmann into the MSB; this triggered the base to sound pressure-loss alarms automatically. There, the crew performed cardiopulmonary resusciation on Krausmann until he regained consciousness 1 minute and 39 seconds after the accident. He suffered from ebullism-induced haemorraghes under the skin and in the nasal cavities, as well as evaporative cooling and a painful earache, while swelling caused by ebullism could be largely suppressed because of the space suit; none of Krausmann's injuries were permanent and he recovered after six months.

The decompression accident was the result of an O-ring connecting the airlock chamber to the two high-pressure nitrogen and oxygen storage tanks breaking and venting the atmosphere into the near-vacuum lunar environment. After investigating the segment, it was discovered that lunar regolith brought into the airlock by astronauts and their suits rubbed and abraded the elastomer through friction and thus weakened its capability to seal. The mechanical vibrations of the "camp-out" system ultimately caused it to break, and the breach allowed the highly pressurized atmosphere to vent into space. Moreover, Reichenbach's efforts to rescue Krausmann by repressurizing the airlock inadvertently widened the breach gap and immediately emptied the tanks of their remaining replenishable supply of air. The loss of the airlock storage air and amounts of the station atmosphere meant Haller 93 EVA activites were greatly reduced, and repairs to alleviate the damage could not be undetaken.

On September 19, 1994, the Haller 94 Expedition added the MAM to Haller Base, in recognition of Falkenhall's aging hardware and the threat of near-constant lunar soil exposure to technology and sensible components. A fully recovered Lukas Krausmann returned to Haller Base on July 4, 1995, with the Haller 96 Expedition.

Haller 03 Expedition (2003)

The ascent stage of LSAM-32 Entdecker carrying the crew of the Haller 03 Expedition, after their 250-day long stay in Haller Base, exploded approximately 21 seconds after its departure take-off from the lunar surface at 11:46 UTC on April 9, 2003, at an altitude of 4 km (13,000 ft). It was the first fatal accident involving Mascyllary astronauts in the history of MAOA, and the crew members were the only humans to have died in space and on another celestial body apart from Aurorum.

The examination of the televised video footage of the launch revealed that the hot combustion products of the ascent propulsion system (APS), using hypergolic propellant, travelled back inwards into the rocket engine and triggered the contained high-pressure combustion of the entire fuel, thus causing the capsule's disintegration. Once the control valves of the Aerozine 50 fuel and dinitrogen tetroxide (N2O4) oxidizer tanks were opened, the malfunctioning system of pressurized helium, which was charged with forcing the propellants into the combustion chamber, damaged the surrounding engine through unusually super-cold adiabatic expansion and allowed the fuel and oxidizer to react uncontrolled. Because it was outside the combustion chamber but inside the engine segment, the gasses expanded rapidly in an explosion that destroyed the ascent stage.

The accident resulted in the death of all four astronauts on board the capsule. After the loss of the Haller 03 Expedition, MAOA halted all planned Haller Base missions and grounded the Haller Base program for one-and-a-half years. Prime Minister Konrad Folln and the Reichsrat subsequently established the Herzberg Entdecker Commission to investigate the disaster, and its concluding report prompted MAOA to introduce numerous safety changes and redesigns of the technology in question, particularly the modification of the control valves and the heating of the pressurization gas through a heat exchanger with the chamber's ambient temperature. The report also criticized MAOA for its organizational and work-place culture, citing it as the proximate cause of the malfunction. In actuality, MAOA was well aware of the potential of a pressure-fed engine failing catastrophically by as early as 1986; more importantly, engineers who had discovered apparent damage to the cooling system of the helium gas as the Atlant-3 was assembled on September 24, 2002, five days before launch, were disregarded and their concerns ignored by MAOA managers.

As a result, MAOA Chief Director Clemens Weinstock was forced to resign after the report's release on August 13, 2003. In late 2004, the Haller Base program continued with the launch of CSM-122 Agretta and LSAM-33 Halie of the Haller 04 Expedition. The remains of the astronauts were transferred on LSAM-33 Halie from Luna to Aurorum, which was recovered by the aircraft carrier MSS Hermann von Martinsen in the Agric Ocean and immediately brought to the military mortuary of Tormundshaff Air Force Base in Aldia on February 2, 2005. On February 26, the transferred astronauts were buried on the requests of their families, while the indiscernible remains were buried at the Entdecker Memorial in the Tülsich National Cemetery in a state funeral; then-Crown Princess of Ahnern Dorothea spoke at their memorial service in St. Lorenz Cathedral in Königsreh. They were each posthumously awarded the Grand Crosses of the Order of the Crown in 2006.