Glorious Rebellion

| Glorious Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

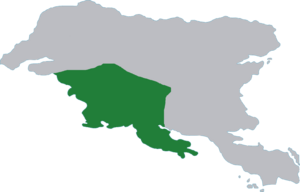

Maximum extent of Gylian territory (green) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Gylias |

|

The Glorious Rebellion (French reformed: Révolte glorieuse) was a massive uprising that took place in Xevden from 1856 to 1868. Gylian revolutionaries, angered by the Xevdenite effort to undermine the Keraþ constitution, staged an insurrection and managed to seize significant territory in the south-western Laişyn plain. There, they proclaimed a republic and implemented radical democratic reforms.

Despite tenacious resistance, the rebels failed to overthrow the Xevdenite regime and were ultimately defeated in 1868. The conflict was marked by fierce violence and atrocities on both sides, with scorched earth tactics and summary executions being commonplace.

Xevden's defeat of the rebellion came at a high price, and authorities took a conciliatory approach afterwards to dampen unrest. The rebellion marked a defeat for the confrontationist faction of the Gylian ascendancy, and the advantage passed to the constitutionalist faction for several decades.

Background and outbreak

The Gylian revolution of 1848 had forced the Xevdenite authorities into a tactical retreat, and one of the most significant concessions was the convening of the first Gylian national assembly to write a new constitution.

The Keraþ constitution, presented in 1849, was a remarkably advanced liberal and democratic document for the era, and it was met with reluctance by the Xevdenites. The Xevdenite parliament attempted to water down the document by debating and voting on it piecemeal rather than integrally, which incensed public opinion.

Beneath the surface calm of the Keraþ assembly, an unstable dual power situation existed: Gylian radicals and reformists maintained a united front, with riots and kyðoi attacks maintaining pressure on Xevden from outside the assembly, while Xevden's ruling class split between reactionaries and pragmatists, both of which grew alienated with king Ŋarny's vacillation and erratic policy.

While the ruling Party of Order could be convinced to grant several concessions to defuse the revolutionary mood, it balked at the socioeconomic provisions of the Keraþ constitution, which for the Gylians were non-negotiable.

Historian Lere Sineşe writes that "there was no single final straw" that triggered the Glorious Rebellion, but more of a steadily building unrest caused by Xevdenite stalling of the constitution, and continued Gylian agitation to pressure them. The isolated uprisings and protests gradually gathered steam and merged into a cohesive, unified revolt in 1856.

Republic

Gylian Republic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1856–1868 | |||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||

| Capital | Iásas | ||||||||

| Government | Directorial republic | ||||||||

| Legislature | Popular Assembly | ||||||||

| Historical era | Gylian ascendancy | ||||||||

• Established | 1856 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1868 | ||||||||

| Currency | Republican aspis | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

One of the centres of the rebellion was Iásas, where a republic was proclaimed. This unrecognised state is conventionally referred to as the Gylian Republic (French reformed: République gylienne), by analogy with the Republic of Makarces.

The term specifically indicates the impact of the Gylian ascendancy and common Gylian identity, as opposed to the less unified Rebellion of 1749.

At the height of the rebellion, the republic occupied territory encompassing all of modern-day Tomes and Nauras, significant parts of Elena, Arsad, Ḑarna, and small parts of Kausania and Envadra.

Its capital was at Iásas, and other large cities under its control included Argyrokastron, Vilêna, Nikopolis, Releş, Keraþ, Deðras, and Riáona. Control of Keraþ, the site of the national assembly, was a significant symbolic victory for the insurgents.

The rebels implemented radical democratic reforms in their territory. Popular assemblies were revitalised from the 1848 revolution and transformed into instruments of direct democracy at the local level. A directly-elected legislature, the Popular Assembly, was established, and executive power invested in a 5-member directory, the Executive Council. The Keraþ constitution was implemented, now without the compromises such as an elective monarchy.

Numerous far-reaching economic reforms were implemented:

- Schools and hospitals were nationalised and made free.

- Assistance for the poor was introduced, including money, food, clothing, and goods.

- The Executive Council took control of mechanisation, purchasing and distributing machinery in order to raise wages and reduce unemployment.

- A decree was passed that guaranteed work for all residents, and national workshops established for the purpose.

- Land reform was carried out in rural areas, often simply through driving out or killing landlords en masse, and promotion of communal land.

Universal conscription was introduced for the duration of the conflict. The Executive Council saw one of the advantages of controlled mechanisation as both raising quality of life and freeing up more people for military service. The armed forces represented a mix of conscripted citizens, former soldiers who'd defected to the republic, and kyðoi organised into cohesive corps.

The republic created its own currency, the aspis (Hellene for "shield"). It was backed by the value of confiscated noble possessions, and included both coins and paper money. It adopted a flag modeled after that of the Liúşai League, with the green and red representing the alliance of farmers and workers, which saw widespread use alongside the blue–yellow–red tricolour of the 1848 revolution.

The republic was notable for enjoying the full support and participation of the Gylian ascendancy, and a majority of its leading figures took part in the venture, ranging from political theorists and social reformers to artists, activists, and philanthropists. The Executive Council reunited the leading political movements of the day — the liberals, conservatives, socialists and emerging communists, and feminists distributed across all factions.

Course of the rebellion

Historians conventionally divide the Glorious Rebellion into three phases: military success in 1856–1862, stagnation in 1862–1864, and reverses and defeat in 1864–1868.

The republic's military strategy was focused on "natural borders": taking and holding territory with strategically advantageous geography, particularly rivers and mountains. It relied strongly on the Kackar mountains to protect its eastern flank, and in the north its advance slowed to caution at the Paksas hills and the Pineios–Ţikona–Rişys rivers line. One major problem for the Gylian rebels was coordinating actions between the relatively cohesive territory of the republic and the less organised, scattered insurrections and kyðoi attacks.

The situation became a military stalemate from 1862 to 1864, marked by setbacks such as a costly failed attempt to capture Náunai, and a retreat from Mayt due to risk of encirclement.

Heated debates consumed the government whether to consolidate their position or push for advances, and whether the thrust of new attacks should be concentrated eastward, past the Ţikona river valley, or northward, to secure more of the Laişyn plain.

Marika Khujadze later commented in one of her books that the republic had a greater geographical disadvantage in the flatland with rivers of south-western Laişyn than the Rebellion of 1749, which started in the more advantageous Salxar mountains.

Xevden gradually regained the upper hand from 1864 to 1868. A combination of advances from the north, forcing the rebels to withdraw from the Nikopolis–Releş–Keraþ corridor, and a breakthrough in the Ţikona valley caused significant risks of salients. Unusually, the eastern Xevdenite forces chose a risky strategy to push northwards, and managed to link up with the other forces at Iásas. From there, they advanced to the western coast, splitting the republic's territory in half.

With the northern pocket being defeated first, the republic retreated to the Nauras peninsula, opposing fierce resistance every step of the way. Its final stand took place in Arxas in 1868, where it was defeated, but inflicted grievous losses on the Xevdenites in the process.

Death toll

It is estimated that a total of 200.000–300.000 deaths occurred during the Glorious Rebellion. The conflict was an example of total war in modern times, particularly on the Gylian Republic's side.

The radical atmosphere of the republic encouraged summary executions, reprisals, and similar abuses against Xevdenites, with the bulk directed against landlords, nobility, and officialdom.

The Gylian rebels' high level of fanaticism on average meant that many preferred to die in battle, even in suicidal or hopeless attacks, than to be captured by the Xevdenites. Both sides practiced scorched earth policies, but the republic took it to its greatest extent once its situation turned desperate.

Retreating Gylians would deliberately burn crops, poison water wells, set fire to fields, and destroy infrastructure. Civilians were evacuated and cities set on fire as Xevdenite capture proved imminent. Anca Déuréy wrote, "We may lose, but we'll leave behind a smouldering ruin in revenge."

Arxas was almost entirely destroyed during the republic's final stand, and was still not entirely rebuilt until after the Liberation War.

Aftermath

The term "Glorious Rebellion" itself reflects the way it was enshrined in popular memory as a valiant failure. Although Xevden managed to suppress the rebellion, the ruling elite was shocked by the tenacity of the rebellion and how close it came to success.

Military success came at the cost of horrendous casualties, the burden of recovering from the systemic destruction inflicted on the south-west, and a Gylian ascendancy emboldened rather than weakened by the suppression.

The international context, if it disadvantaged the Glorious Rebellion, proved no more favourable to Xevden. Ossoria's contemporaneous Legislaturist War had ended in victory for High Queen Gwenivar Iarann, who paired her political suppression with social reforms specifically to avoid the "alliance of farmers and workers" in evidence among Gylian revolutionaries. The Red War turned Ruvelka into Tyran's first socialist state, although too late to save the Gylian Republic.

At such a juncture, counter-revolutionary reprisals and terror risked arousing international ire.

After an attempt to try leaders of the rebellion degenerated into a humiliating farce, the pragmatists assassinated the erratic king Ŋarny in 1870, and his successor Ernax immediately proclaimed a general amnesty and reconciliation.

The defeat of the Glorious Rebellion temporrarily gave the upper hand to the Gylian constitutionalists, while simultaneously empowering the Xevdenite pragmatists. A window of opportunity opened for a succession of governments to grapple with the "Gylian Question".

The 1848 revolution and Glorious Rebellion became important mobilising myths for Gylian nationalism, glorified in popular memory and the subject of Alscia's first epic films, and served as a precedent for the Gylian consensus.

Commentators from across the political spectrum credit the policy of national workshops and state control of industrialisation as far-sighted, presaging Alscia's state-driven development and Gylias' Institute for the Protection of Leisure.

United by the struggle against Xevden, the Gylian Republic uniquely managed to please all political sides:

- Liberals and conservatives lionised its application of the Keraþ constitution and experiments with direct democracy.

- Socialists were emboldened by the successful worker–farmer alliance.

- Communists and anarchists lauded its willingness to use force for revolutionary purposes, particularly in carrying out land reform and expropriation.

It symbolically marked an important bridge in Gylian history between the Liúşai League and the Free Territories, and emboldened Gylians by displaying the strength of their cause a century after the suppression of the Rebellion of 1749.

The enduring memory of the Glorious Rebellion and the Liberation War have been linked by some commentators to a tendency among the Gylian public of sympathy for "physical force radicalism" which has at times strained foreign relations, such as sympathy for the Labor Underground and far-left insurgency in Delkora, the Zemplen Independence Movement in Ruvelka and Syara, and the anarcho-syndicalists in Æþurheim's civil war.

The Aén Ďanez government's attempt to exploit this tendency in supporting Ossoria's Republican Faction backfired severely, causing the Ossorian war crisis of 1986.