Alscia: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 552: | Line 552: | ||

The '''seal of Alscia''' (''Stemma d'Alscia'') depicted a blue wheel with eight spokes, symbolising progress. | The '''seal of Alscia''' (''Stemma d'Alscia'') depicted a blue wheel with eight spokes, symbolising progress. | ||

"[[Arise, Gylians]]" was chosen as its national anthem. | "[[Arise, Gylians]]" was chosen as its national anthem. | ||

Another patriotic song, "[[Primavera di bellezza]]", was seen as the "unofficial national anthem" due to its widespread popularity. | |||

==Foreign affairs== | ==Foreign affairs== | ||

Revision as of 15:53, 13 December 2022

Alscia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1908–1939 | |||||||||

| Anthem: Arise, Gylians | |||||||||

Alscia (dark green) within the Cacertian Empire (light green); map does not include TACS | |||||||||

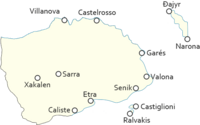

| Capital | Etra | ||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Alscian | ||||||||

| Government | Parliamentary democratic constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||

• 1908-1939 | Donatella Rossetti | ||||||||

| Legislature | Legislative Council | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 1904–1908 | |||||||||

| 1908 | |||||||||

| 1939 | |||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1935 | 1.668.363a | ||||||||

| Currency | Alscian lira (₤) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Gylias |

|

Alscia (Gylic transcription: Alşa) was a Gylian polity that existed as a protectorate of the Cacertian Empire. It was established in 1908 on territory occupied after the Cacerta-Xevden War. Its territory corresponds to the modern Gylian regions of Arxaþ, Alţira, and Nerveiík-Iárus-Daláyk, and the Cacertian region of Molise.

Alscia received autonomy and responsible government rapidly, as part of contemporary Cacertian imperial policy. It accepted the Empress of Cacerta as head of state, and an elected legislature that chose the Governor. The government used a strategy of constructive ambiguity to portray Alscia as an independent country under Cacertian protection; a variety of formal designations were in use.

Alscia experienced strong economic growth and general prosperity as part of the Empire. Economic development included significant industrialisation, mechanisation of agriculture, and sophisticated infrastructure. The government took a leading role in economic planning and social policy.

The environment of stability and prosperity produced a rich social, artistic, and cultural environment. Alscian society was famed for its modernity, liberalism, and openness to experimentation. It benefited from widespread access to the media and high levels of civic engagement. It became a centre of Gylian media and dissidence, with a key role in disseminating and popularising radical ideas. Consciousness of this status shaped Alscian identity and foreign policy, dominated by the Alscian Border War against Xevden.

Alscia played a mixed role in the dissolution of the Cacertian Empire. It voted to join the Free Territories in 1939, and thus ceased to exist.

Name

"Alscia" is the Italian acronym of the territories that formed it: Arxaþ (Arsciata), Alţira (Alzira), and Iárus (Iarus). Molise was not included in the acronym as it didn't exist at the time.

It is rendered in French as L'Alscie. The Gylic languages use the term in its original Italian spelling. The most common Gylic transcription is Alşa, but the variant spelling Alşia also exists, reflecting the alternative pronunciation.

Due to the government's policy regarding symbols, there is no official designation for Alscia. Numerous terms were applied throughout its existence. In a domestic and international context, terms emphasising statehood were used, such as "realm", "crowned lands", or "state" in personal union with Cacerta. In an imperial context, terms emphasising Cacertian protection were used, such as "protectorate", "union", and "province".

The "hurried province" became a popular poetic term for Alscia, in use even among those who otherwise emphasised Alscian self-determination.

Creation

Following its victory in the Cacerta-Xevden War (1904–1908), the Cacertian Empire gained several Xevdenite territories in the Treaty of Ðajyr. Most of these were Gylian territories in the north-east. One notable cession was Iárus, which Cacerta demanded to obtain a naval base off the coast of Nerveiík Peninsula, enabling its navy to easily reach Velouria in the event of conflict.

Alscia benefited from Cacertian imperial policy at the time, which had shifted towards greater acommodation in response to local tensions with Allamunnika and Lirinya. In practice, Alscia was subject to Cacertian suzerainty: it enjoyed extensive self-rule and was nominally independent, but integrated into the Empire.

Politics

Alscia's political system largely followed the model of Cacerta: a constitutional monarchy, governed by a parliamentary system exercising a fusion of powers.

The Empress of Cacerta was officially the head of state. Alscia created its own, legally distinct monarchy, giving her the official title Queen of Alscia (Italian: Regina d'Alscia), which was incorporated into the Empress' full title.

Government

The Government of Alscia (Governo d'Alscia) represented the executive branch. It was composed of 12 ministers, which formed the Council of Ministers (Consiglio dei Ministri).

The head of government was known as the President of the Council of Ministers (Presidente del Consiglio dei ministri), or more commonly as the Governor (Governatore).

The Governor appointed the ministers, and the government as a whole was approved by the legislature.

Throughout its existence, Alscia was governed by the Donatella Rossetti government.

Legislative Council

Legislative Council of Alscia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| History | |

| Founded | 1908 |

| Disbanded | 1939 |

| Succeeded by | General Council of the Free Territories |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 70 |

Length of term | 4 years |

| Elections | |

| Single transferable vote | |

First election | 1908 |

Last election | 1936 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Casa del Consiglio, Etra | |

| Constitution | |

| Constitution of Alscia | |

The Legislative Council (Consiglio Legislative) was the unicameral legislature. It was formed of 70 members, elected by single transferable vote every 4 years. It was also informally called the "Parliament" (Parlamento).

It had a system of commissions (commissioni parlamentari) in order to scrutinise bills, monitor the government's work, and approve budgets.

The Popular Progressive Front (FPP) held a supermajority in the Council throughout its existence. The opposition was formed by the Party of Freedom (PdL), Communist Party of Alscia (PCA), and independents. Nevertheless, Alscia had a vibrant political life, and the FPP saw competition over influence between liberals and socialists.

| Election | FPP | PdL | PCA | Ind |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1908 | 60 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| 1912 | 65 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 1916 | 64 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 1920 | 66 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| 1924 | 63 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 1928 | 68 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1932 | 62 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| 1936 | 61 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

Law

Alscia had a civil law system, separate from the rest of the Empire. It was based on the Constitution of Alscia, which declared Alscia to be a parliamentary democracy and a state in personal union with Cacerta. The text of the constitution was symbolically based on the Keraþ constitution.

The Alscian civil code, commercial code, and penal code were assembled in 1910–1914. A notable provision of the commercial code banned foreign citizens from owning property in Alscia, which was a source of discord with the Empire. Nationality law defined Alscian "nationality" as equivalent to Cacertian citizenship, thus making all Alscians dual nationals by default.

The judicial system had three levels: courts of first instance at the local level, courts of second instance at the intermediate level, and the High Court of Cassation (Alta Corte di Cassazione) as the court of last resort.

Law enforcement was provided by the Alscian Police (Polizia d'Alscia).

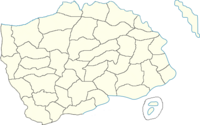

Administrative divisions

Alscia was divided into comuni ("municipalities") for the purposes of local governance. There were 43 comuni in total.

Each comune had a legislative body, the consiglio comunale ("municipal council"), and an executive body, the giunta comunale ("municipal committee"), headed by a mayor (sindaco).

Local elections took place every two years, using single transferable vote.

Direct democracy

Alscia was known in the Empire for its experimentation with direct democracy mechanisms. These included systems of popular initiative and referendum, allowing voters to directly propose and approve laws, primary elections for parties to choose candidates, and recall elections for elected officials.

Status

Officially, Alscia was in personal union with Cacerta, and thus part of the Empire. It accepted Cacertian military protection and primacy over foreign policy. Nevertheless, it became famous for its symbolic assertions of independence, and testing the limits of its autonomy.

Alscia was not represented in the Cacertian Parliament, and did not take part in any elections other than its own. It had its own legal system, and a constitution that did not mention what matters were reserved for the Empire. Imperial legislation and regulation were transposed into Alscian law for use in the legal system.

Historian Herta Schwamen writes that Alscia benefited significantly from the indulgence of queens Elliana and Rosalia, which had some sympathy for the Gylian cause and tolerated these "symbolic mutinies" as harmless, in contrast to the Ultranationalist Party who saw Alscia as "a wayward province to be brought to heel".

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1910 | 623,700 | — |

| 1915 | 892,042 | +43.0% |

| 1920 | 1,131,974 | +26.9% |

| 1925 | 1,293,222 | +14.2% |

| 1930 | 1,476,053 | +14.1% |

| 1935 | 1,668,363 | +13.0% |

| Source: Alscian census | ||

Alscia experienced rapid population growth: its approximately 500.000 residents in 1908 rose to 1,7 million in 1938. Population growth was influenced by high total fertility rate, declining infant mortality rates, and strong immigration, especially of Gylian refugees from Xevden.

The government conducted censuses every 5 years, starting in 1910.

Ethnicity and language

Alscia's population was notably heterogeneous, comprising multiple Gylic and non-Gylic populations. Demographic trends included an influx of Italians from Cacerta and Megelan (the latter forming the Free Megelanese community), and a strengthened French community through migration from Venetia.

The 1935 recorded ethnolinguistic identification as follows:

|

|

Alscia had no official language. All languages were recognised as regional languages and received official protection in areas where they were concentrated, including their use in education, administration and public life together with Italian, English, and French.

Italian and French were used as common languages among Gylians, and benefited from strong promotion. They became refined sociolects among the educated and upper class; it was common for cities and locations to use Italianised spellings together with their native name. Later, Cacertian influence started the emergence of English as an additional common language.

Urbanisation

Alscia experienced rapid urbanisation. The total population living in urban areas increased from 24% in 1908 to 72% in 1935 — a remarkable increase by Gylian standards.

Urban settlement was largely concentrated on the eastern coast, particularly on the Caliste–Etra–Senik–Valona–Garés corridor.

The 1935 census recorded city populations as follows:

| City | Residents |

|---|---|

| Etra (Etra) | 160.771 |

| Senik (Senicco) | 155.800 |

| Valona | 148.202 |

| Caliste | 130.948 |

| Garés (Garezzo) | 105.315 |

| Xakalen (Ciaccaleno) | 103.624 |

| Castelrosso | 100.427 |

| Sarra | 85.242 |

| Ðajyr (Dagiura) | 73.625 |

| Narona | 64.281 |

| Other cities | 72.986 |

Religion

The largest religion by practitioners was Concordianism. There was also a strong presence for the religions of traditional non-Gylic communities, including Kisekidō, Hellene religion, Germanic religion, Norse religions, Arordi, and Lusitan and Gallic religions. Sofianism established a notable foothold in the province, aided by Cacertian settlement.

Only a minority of Alscians were members of officially recognised religious organisations. The majority did not identify with a particular religion, and some were irreligious.

The Gylian ascendancy's aspect of animosity towards monotheism and organised religion developed into official hostility. The government intervened in regulating religious organisations specifically to promote polytheism and non-organised religions. Proselytism was banned, and conversions and disaffiliations were legally unrecognised.

Economy

Alscia experienced rapid economic growth, social progress, and modernisation. It benefited from imperial development policy, which meant most of its resources were used for its own development, and the integration into the Empire, which brought additional capital flows and investment.

The economy went from primarily agrarian to industrial. The proportion of workers employed in industry tripled, from 19% (1915) to 59% (1935), while agricultural employment declined from 81% (1915) to 28% (1935).

Agriculture was transformed by land reform, modernisation and mechanisation. Expanded irrigation, crop improvements, and application of agricultural science increased productivity. The sector was dominated by tropical cash crops, such as rubber, sugar, cocoa, coffee, and tobacco. Crops of rice, sorghum, tea, and tropical fruits were mainly cultivated for the domestic market. Animal husbandry revolved around poultry, pigs, cattle, and sheep, which also produced milk, eggs, wool, and leather in addition to meat.

The province underwent accelerated industrialisation and diversification. Significant industries to emerge included textiles, metalworking, food processing, meatpacking, cement, machinery, and automobiles. Forestry and mining extracted natural resources to be processed: wood, gold, silver, copper, some poor-quality coal. Iárus became the main centre of provincial shipbuilding. The Karys, Tarna, and Nazar were dammed for hydroelectricity and irrigation.

The armaments and munitions industry grew as a result of the Divide War and Border War.

The stable business climate allowed commerce to flourish. The Bank of Alscia (Banca di Alscia) was established as the province's central bank, and numerous banks, credit unions, mutual savings banks, and similar institutions emerged. A stock exchange was chartered at Caliste in 1917.

Infrastructure

Alscia's development necessitated substantial transportation infrastructure, which became an essential focus of policy. The government completed extensive public works, building roads, railroads, waterways, airports, telecommunications, and an electric grid. The Salen Canal, completed in 1916, linked the cities of Sarra and Xakalen, and increased traffic on the Karys and Tarna.

In 1935, Alscia had extensive networks of modern roads, railroads, canals and navigable rivers. Cities had systems of electricity, water, telephone and telegraphs, while the largest cities had extensive public transport networks of trolleybuses and trams. Etra, Senik, Garés, and Ðajyr were the province's most important commercial ports. Iárus was connected to the mainland by ferry and airplane.

After the establishment of Royal Cacertian Air Carriers, most of Alscia's large cities built fields with airship hangars and mooring masts to accommodate airship routes.

Government policy

The Alscian economy was marked by a state-driven development model, later called Donatellism. The government played a leading role in regulating the economy and guiding Alscia's development, with the private sector carrying out investment and production based on its directions.

The main instrument of economic policy was the Alscian Development Company (Società per lo Sviluppo di Alscia, SSA). The SSA provided loans, subsidies, and other measures to encourage industry, and helped steer investment into areas that would stimulate the economy. Since private companies shouldered the costs of modernisation and development, the government could maintain a balanced budget and good fiscal conditions.

The SSA created a distinctive element of the Alscian economy: "shareholderism" (azionismo). The SSA owned shares in most Alscian companies, and held majority shares in essential areas — public utilities, transport, natural resources. These shares were distributed to Alscians through vouchers, allowing for an egalitarian distribution of economic gains to the populace.

The activism for reform and efficiency produced a strongly regulated market. Alscia accumulated extensive laws guaranteeing consumer protection, labour rights, and fair competition.

At the same time, the SSA and government supported and tacitly cooperated with the Gaulette conglomerate due to Arlette Gaubert's humane economy principles, allowing it to monopolise Alscia's private sector by the 1920s. The government, SSA, and Gaulette thus formed the "iron triangle" at the heart of the Alscian economy.

Income tax rates were progressive, with 25 brackets ranging from 2% (lowest) to 64% (highest). Corporate tax rates increased from 10% in the 1910s to 20% in the 1930s. Other significant sources of income included property tax, excise on various goods, inheritance tax, and land value tax. Wealth taxes and capital levies were imposed at certain points during the Divide War and Border War.

Cooperatives

Cooperatives and mutual organisations were a meaningful presence in the Alscian economy, building on the strength of the cooperative movement formed in the Gylian ascendancy. Cooperatives were strongly represented in agriculture, banking, insurance, and retail, and consumer and worker cooperatives grew in size during the province's lifetime.

A 1936 estimate held that cooperatives represented nearly a third of Alscian economic activity. The economy came to be defined by the confluence of public sector, Gaulette-monpolised private sector, and steadily growing cooperative sector.

Currrency

Alscia had its own currency: the lira (₤). It was issued by the Bank of Alscia, and its value was fixed to the Cacertian inganarre. The inganarre also circulated freely and interchangeably in Alscia, and the Cacertian government treated the Alscian lira as simply a local issue of the inganarre.

Labour movement

Alscia was a leader in advanced social policy and labour law in Tyran. The labour movement benefited from worker-friendly legislation, most significantly compulsory unionism.

All trade unions in Alscia were confederated into a national trade union centre, the Alscian Labour Union (Unione Alsciana del Lavoro, UAL). Besides workplace organising, the UAL provided numerous services and benefits to its members, including education, entertainment, leisure, cultural activities, and welfare. It also campaigned for improving workplace conditions — improved cleanliness, better hygiene, protective work attire, renovations of outdated factories, new canteens for workers, smoking-free rooms, cleaner working spaces, and so on.

The UAL was the site of ideological antagonisms. There were broadly two tendencies. One was the corporatism of the Donatella Rossetti government and Valentina Potenza, which advocated class collaboration, and appealed to the labour aristocracy. The other was radicalism and syndicalism, which sought to overthrow capitalism.

Valentina's efforts to keep the UAL "strong but toothless" largely succeeded. She was instrumental in creating a climate where unions were steered towards self-restraint, and communists and anarchists were purged from unions. The bulk of the UAL leadership was largely conservative, docile towards the government, and in practice broadly liberal, or at most social democratic.

Society

Alscia experienced widespread prosperity and significant social and cultural development. Alscians enjoyed a high standard of living: in 1935, Alscia's net income was 60% that of Cacerta, and average wages 75% of Cacerta's.

Infrastructure and communications were in very good quality, and the majority of people had access to adequate sanitation, running water, heating, telecommunications, healthcare, and education, and had their basic needs met. Urban comuni oversaw ambitious slum clearance and public housing construction programs, which together with housing cooperatives gave the province a robust housing stock.

Women and minorities gained equality in the public sphere and made significant advances. Women were well-represented in Alscian politics and intellectual life — the Donatella Rossetti government was majority female. Alscian feminists formed ties with Cacertian feminists, whose movement was strong during Elliana's rule, and the province adopted scientific sex education and regulations on prostitution.

The LGBT community thrived as a result of liberalisation of laws and society, and the large cities became centres of LGBT culture. The GSRAA was established in 1914, while culturally the mauve circle attained prominence and notable influence.

Compulsory education was a key priority for the government, and Alscia developed an efficient public education system, following the Cacertian model. Primary and secondary education were compulsory from the ages of 8 to 14; higher education was conducted in universities, art academies, and polytechnics. The most prestigious universities were the Imperial Universities (Università Imperiale), located in Etra, Senik, Valona, Garés, and Ðajyr.

The public health system was based on a network of public hospitals and local clinics and polyclinics, the latter being the more numerous. Effective sanitation and mass vaccination campaigns rid Alscia of infectious diseases such as typhoid fever, plague, and tuberculosis.

Social policy was strongly progressive, and produced a mixed welfare state where government programs coexisted with social insurance schemes and the mutual societies inherited from the Gylian ascendancy. Benefits provided included: medical, accident, and disability insurance; old age pensions; unemployment compensation; family allowances; free school meals and schoolbooks.

The "hurried province"

Alscian society was characterised by prosperity, optimism, and enthusiasm for modernisation. Promoted by both Donatella's dominant figure and widespread social activism, life in Alscia was defined by the "mania for modernity", reflected in the expansion of liberal values and experimentalism and creativity in the arts. This earned it the nickname "the hurried province".

The efficiency movement was central in provincial life, with Valeria Valente its greatest representative. Fueled by industrialisation, there was a push for increasing efficiency and eliminating waste in all areas of life: scientific management in economy, progressive reforms in public life, and mobilisation of research in service of public policy. Applied sceince yielded notable benefits for agriculture and urban planning, while absence of prohibition produced pioneering research into the effects of drugs.

Donatella's promotion of science and progress reverberated in other areas of public life: an incipient technocracy movement emerged.

Class structure

Although Alscia was not a classless society, "shareholderism", cooperativism, and interventionism made it highly egalitarian. There was high social mobility and a relatively small range of wealth. Robust labour unions and fair competition legislation contributed to a high standard of living on average, and prevented concentration of wealth even as Gaulette monopolised the private sector. The majority of Alscians enjoyed relatively easy access to consumer goods and luxury goods, particularly clothing and jewelry.

Differentiation between classes was largely based on occupations. The working class rose as a result of industrialisation. Modernisation, efficiency, and the civil service helped the middle class grow in size and complexity. Urbanisation unexpectedly benefited rural areas: migration to the cities stabilised the size of farm plots. Several new professions emerged, including elevator attendant, tray vendor, and telephone operator.

Donatella and her colleagues in il palazzo sought to create an Alscian upper class with a culture of noblesse oblige, which would embody social responsibility, high standards of cultivation and conduct, and serve as pillars of the community. The Office of Civil Honours (Ufficio degli Onori Civili, UOC) administered the Alscian honours system, which included symbolic titles of nobility and orders of merit, both rewarded for distinguished service and achievements to Alscia. These were:

|

Alscian titles of nobility

|

Alscian orders of merit

|

Titles and orders were mainly awarded for philanthropy, cultural achievements, support for the arts, and eminent service to the community, such as the hosting of salons. The UOC enforced strict moral standards for recipients, and could publicly revoke awards for misconduct or criminality. Titles of nobility were non-hereditary and brought no additional privileges, although several nobles sought to live up to their status by constructing stately homes.

The government was prolific in awarding titles and orders. The system encouraged philanthropy and art patronage among the wealthy. Arlette Gaubert became an icon of "humane capitalism", inspiring wealthy Alscians to similarly use their wealth for philanthropy, art patronage, and civic improvement.

Certain ethnolinguistic groups were more well-represented among the ranks of Alscia's upper class, including Miranians, French, Italians, and Hellenes.

Media

Alscia had a thriving media, and had one of the highest per capita numbers of newspaper readers and radio listeners in the Empire. The number of local newspapers and magazines reached 50 by 1927. Publishing was a robust industry, and the province became the main source of works in the Gylic languages.

The two largest newspapers, The Etra Echo and The Senik Sun, engaged in a lighthearted rivalry. Their competition spurred significant advances in the creation of a popular press: reliance on mass circulation and advertising, mixture of news and entertainment, cartoons and comic strips, competitions for prizes. Their sponsorship of the Race Around the World was a major event in the history of Gylian newspapers, and had a lasting impact on international recognition of Gylians.

One of its emblematic magazines was Risveglio Nazionale, renowned for its ambitious nation-building and state-building ethos.

The media played a pivotal role in driving social activism. With its strongly populist tone and hard-hitting coverage, the investigative journalism of the period produced exposés of political scandals, corporate malfeasance, administrative failures, and social issues. The wide range of issues brought to public attention fueled the push for safer workplaces, consumer protection, fair competition, and administrative reform that led to effective regulation.

Several journalists achieved wide recognition: Margherita Martini as a perceptive and engaging chronicler of Alscian life, Liza Jane as an investigative journalist specialising in undercover exposés, and Elisa Boland as an influential progressive commentator and activist; the latter two particularly for competing in the Race Around the World.

The province's public broadcasting company, the Society for Alscian Radiodiffusion (Società di Radiodiffusione Alsciana), was established in 1912. It operated a telephone newspaper service, modeled after L'Araldo Telefonico, before switching to radio services in the 1920s.

Radicalism

Alscia became a haven for Gylian radicals. It was a staunch supporter of the Gylian opposition throughout Xevden's disintegration. As the largest Gylic publishing and media market, it played a key role in printing and disseminating radical texts to Xevden. The SRA built transmitters next to the borders and in TACS, broadcasting to Gylians in Xevden.

The effort to bolster and aid the Gylian opposition also caused a gradual radicalisation of Alscia itself. Public exposure for ideologies like anarchism, communism, and socialism increased, and gradually they gained increasing support and acceptance.

In addition to Gylian radicalism, Alscia also welcomed and sheltered dissidents and political exiles from other nations, such as the Revive Quenmin Society.

Culture

Alscia saw a flourishing of Gylian culture and the arts. The largest cities developed into bustling cosmopolitan cities, home to and stopover for artists, musicians, poets, and writers from all over the Empire and beyond. A network of fashionable cafés, teahouses, restaurants, and salons developed which contributed to the fertile social and artistic environment.

Sustained contact with Kirisaki, Akashi, Cacerta, and Megelan served as a key link in the transmission of contemporary arts and popular culture to Alscia.

Alscian culture was shaped by the craze for all things modern. Artistic movements glorifying modernity, like Art Nouveau and Art Deco, and various avant-garde currents, became popular.

Radio and cinema emerged as art forms, with the first Gylian films and animation being produced. Literature, art, and popular music were similarly invigorated. New genres emerged, including proletarian literature, genre fiction, revitalised erotic literature and pornography, and documentary films, particularly city symphony films.

In fashion and aesthetics, ideals of elegance developed based on a synthesis of Miranian, French, and Italian influences. Androgyny chic became highly fashionable in Alscia; Sofia Westergaard commented that on her first visit, "I had never seen so many women wearing suits and ties before." The popularity of androgyny chic reflected the blurring of gender roles and the emancipated flapper generation.

Sport

Sports were established as a leading pastime in Alscia. The most widespread sport became football: by the early 1930s, nearly all secondary schools and universities had their own football teams. Cycling culture also developed notably, and the first motorsport events were organised. The socialist, labour and anarchist movements engaged in promotion of sport, establishing their own sports organisations and clubs.

The Alscian Sports Association was established in 1921 to promote sport in the province.

Identity

Alscian identity was shaped by consciousness of their status as "lucky Gylians" (in comparison to those resisting in Xevden) and its cultural explosion. The unprecedented rapid development gave much of Alscian popular culture an exciting atmosphere, reflected particularly in fashion, Art Deco art and architecture.

Alscians' abiding preoccupation with the ultimate liberation of all Gylians manifested in a strong impulse to display symbolic independence and test the limits of their autonomy. Domestic political discourse described Alscia as a state; the law and judiciary avoided referring to Cacertian legislation or institutions; the Empress was referred to in her capacity as Queen of Alscia. In Cacerta, Alscians came to be known as "reluctant subjects" as a result.

Symbols

Alscia adopted two official symbols.

The flag of Alscia (Bandiera d'Alscia) was a horizontal triband of blue-white-blue. The design and colour scheme were based on the flag of the Liúşai League; the differences were a lighter shade of blue and stripes of equal length. The blue symbolised the sky and the ocean, alluding to Gylians' seafaring traditions.

The seal of Alscia (Stemma d'Alscia) depicted a blue wheel with eight spokes, symbolising progress.

"Arise, Gylians" was chosen as its national anthem.

Another patriotic song, "Primavera di bellezza", was seen as the "unofficial national anthem" due to its widespread popularity.

Foreign affairs

While Cacerta reserved the domain of policy affairs, the Alscian government nevertheless engaged in diplomacy. It opened legations in several countries, and created an international organisation to promote Gylian culture and relations.

Notable achievements of Alscian diplomacy were the resumption of official relations with Kirisaki, and the establishment of official relations with Akashi and Delkora. Relations with Delkora reached an early pinnacle in the 1930s, aided by the friendship between Donatella Rossetti and Sofia Westergaard.

Foreign policy was mainly based on the principles of affirming Gylian self-determination and keeping pressure on Xevden.

Military

Alscia maintained its own military force, known as the Border Guard (Guardia di Confine). Its primary purpose was to guard Alscia's borders against Xevden.

Despite its name, the Border Guard was a full-fledged military, including army, navy, and air forces. Alscia maintained conscription, regardless of sex, with alternative civilian service offered for conscientious objectors. The combination of conscription and imperial military expertise made the Border Guard a serious force in southern Siduri.

The Border Guard engaged in unofficial conflict with Xevden during the Alscian Border War, which consisted of incursions, skirmishes, harassment of Xevdenite forces, and support of Gylian rebels.

Alscia unofficially expanded through annexing additional territory during the Border War, which was organised as TACS. To maintain the legal fiction behind the conflict and avoid involving Cacerta, TACS were not included in official Alscian statistics, but instead received their own oversight.

Dissolution

Alscia played a complex and sometimes contradictory role in the dissolution of the Cacertian Empire. Alscian support for strengthening and reform of the Empire was counterbalanced by hostility to centralisation, and poor relations with Ultranationalist governments. The Liberation War erupted as the deadline for imperial dissolution approached, and the growing radicalism of Alscia translated into support for joining the Free Territories.

Alscia's future path was put to a referendum on 18–19 February 1939. The options offered were joining the Free Territories, or continuing as an independent state in association with Cacerta. The electorate voted to join the Free Territories by a landslide, with 72% of the vote. The result was a partition: the northern comuni that had voted for independence remained in Cacerta as Molise, while the majority of comuni that had voted to join the Free Territories did so.

Alscia officially joined the Free Territories in a formal ceremony on 1 March 1939 in Etra. The process resulted in its dissolution: power was passed to communal assemblies, workplaces were taken over by workers' councils, and comuni were replaced by new administrative divisions.

The transition proceeded faster in some areas than others. For instance, the economy was cooperativised quickly, owing to the existing strength of Alscia's cooperatives, but the Bank of Alscia continued to exist for a few more years, and existing issues of lira remained in circulation as a hard currency.

Legacy

Alscia was the first Gylian polity to be established since the Colonisation War. Coming after the failures of the Republic of Makarces, Keraþ assembly, and Glorious Rebellion, its endurance was a success that significantly boosted Gylian hopes for ultimate triumph over Xevden.

In Gylian history and popular imagination, Alscia is remembered as "an oasis of freedom, culture, and modernity" in the long, arduous struggle against Xevdenite rule. Its widespread prosperity was unprecedented, while its embrace of modernity was influential on Gylian popular culture, giving movements like Art Deco an enduring popularity. The economic model of Donatellism had a lasting impact, laying the foundation for Gylian social security and cooperative economy.

The atmosphere of freedom allowed for the maturation of Gylian politics, as movements like conservatism, liberalism, socialism, communism, and anarchism attained their modern form, and began to have an impact on society. Alscia's innovations later reached fruition with Gylias' practice of direct democracy and widespread participation.

Although Alscia had been envisioned as a temporary entity pending the final victory over Xevden, it lasted sufficiently long to develop its own identity. Anaïs Nin recalled that Alscia had become home to many Gylians, and its dissolution upon entrance to the Free Territories prompted a sense of loss. Several commentators have characterised modern Gylian identity as a compromise between the "rational efficiency" of Alscia and "genial messiness" of the Free Territories.

Nostalgia for Alscia and what it represents remains a potent force in the identities of the regions that had formed it. Arxaþ and Alţira continue to use regional currencies named lira, and imitating the designs of the Alscian lira. The Alscian urban experience was influential on demopolitanism, and most of Alscia's architecture has been extensively preserved. Cities have preserved nomenclature such as streets and landmarks named "imperial", "royal", or after queens Elliana and Rosalia. Two Alscian-era newspapers, The Sunday Thought and The Social Times, survived the Liberation War and continue to be published today.

The "hurried province" is a standard turn of the century setting in Gylian pop culture, particularly for scientific romance, steampunk, and adventure works that commonly evoke its romanticism, optimism, and buoyant progressivism. Notable examples include Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adèle Blanc-Sec and Rubis Cœur: Sky Captain.

Molise's identity has similarly demonstrated an enduring Alscian influence, earning it the nickname of "Cacerta's most Gylian region". Molisentismo, a movement that advocates Molise join Gylias, is a notable manifestation.

Some analysts have seen Alscia as part of a historical trend of Cacertian influence in eastern Gylias, dating back to the Sabrian Empire, and a contributor to the Hellene West and Italian East phenomenon in Gylic languages.

Most of Royal Cacertian Air Carriers' modern airship routes to Gylias continue to use cities in Arxaþ and Alţira as their destinations, reflecting the legacy of Alscia.