Senria

Republic of Senria 썬류우꾜우외꼬꾸 Senryuu Kyouwakoku | |

|---|---|

| Motto: 꼬꾸민노이씨가쌔꼬우호우끼 Kokumin no Isi ga Saikou Houki The People's Will Shall be the Supreme Law | |

| Anthem: 꾜우외꼬꾸꼬우씬꾜꾸 Kyouwakoku Kousinkyoku March of the Republic | |

| Seal: 썬류우꾜우외꼬꾸노몬 Seal of the Senrian Republic  | |

Location of Senria in Kylaris | |

| Capital and largest city | Keisi |

| Official languages | Senrian |

| Recognised regional languages | Isotaman, Esamankur, Cotratic |

| Demonym(s) | Senrian |

| Government | Unitary dominant-party parliamentary republic[1] |

| Reika Okura | |

| Kaori Himura | |

| Seitarou Nakagawa | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| History of Senria | |

| 710 BCE | |

| 1869 | |

| 1918 | |

| 1933 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 609,136.64[2] km2 (235,188.97 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 1.5%[3] |

| Population | |

• 2015 census | 258,751,620[4] |

• Density | 424.78/km2 (1,100.2/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | $9.747 trillion[5] |

• Per capita | $37,670[5] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | $4.484 trillion[5] |

• Per capita | $17,328[5] |

| Gini (2015[6]) | 42.1 medium |

| HDI (2022[7]) | .863 very high |

| Currency | Senrian yen (圓, ¥) (SNY) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (CE) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +30 |

| ISO 3166 code | SN |

| Internet TLD | .sn |

Senria (Senrian: 썬류우꼬꾸, Senryuukoku), known formally as the Republic of Senria (Senrian: 썬류우꾜우외꼬꾸, Senryuu Kyouwakoku), is an island country located in the continent of Coius. It is bordered by the Lumine Ocean to the west and north, the Honghai Sea to the south and southeast, the Rangyoku Strait to the east, and the Bay of Bashurat to the northeast. Senria shares a maritime border with Shangea. Its capital and largest city is Keisi.

The main part of Senria, the Senrian archipelago, is a stratovolcanic archipelago of several thousand islands and islets. Of these, the islands of Kousuu, Tousuu, Yuusuu, and Gyousuu, which make up the majority of Senria's land area and are home to the vast majority of its population, are considered to be the "main islands". Smaller islands within the Senrian archipelago include Kisima, Rousima, Kanasima, Sugisima, and Kaedezima; subarchipelagos within the larger Senrian archipelago include the Isotama and Hibotu island chains. The country also controls the Sunahama Islands, a series of atolls located on the border of the Honghai and Coral seas.

While Senria has been inhabited since the Late Paleolithic, and was supposedly unified by the Emperor Kousou in 710 BCE, traditional records of Senrian history before the 300s CE are typically regarded by historians as heavily mythologized and ultimately unreliable. The first confirmed references to Senria from an external source come in the Yiguoji, a Shangean chronicle from the 4th century CE. The authority of the Senrian monarchy was centralized by a series of reforms in the 5th and 6th centuries, enabling a flourishing of culture and commerce, but began to decline precipitously beginning in the 800s, with power falling into the hands of local lords known as daimyou whose rule was enforced by warrior nobles known as samurai. The ensuing period of prolonged internal division was marked both by regular conflict between rival daimyous and by a renewed flourishing of Senrian culture.

The country was reunified by the Keiou Restoration, beginning in 1869, which saw central authority reestablished under an absolute monarchy; political repression, stalled modernization, and perceived weakness in the face of Shangean and Euclean imperialism in subsequent decades led to the Senrian Revolution, which ended with the formal deposition of the monarchy in 1923. The country played a major role in the Great War, undertaking a program of breakneck industrialization and mass mobilization in response to the invasion of the country and genocide of Senrians by Shangean forces. Senria emerged from the war as an industrial and military power; a new constitution was ratified in 1933, with wartime leader Katurou Imahara establishing a dominant-party regime under his rule. While Senria liberalized somewhat under Prime Minister Kiyosi Haruna, Imahara's Aikokutou remains in power into the present.

Home to 258 million people as of 2015, Senria is the second-largest country in the world by population; its capital, Keisi, is the largest city and metropolitan area in the world. While the Senrian population is overwhelmingly composed of ethnic Senrians, the country is also home to the Isotamans, Esamankur, and Cotratics, as well as Shangean, Ansene, Satrian, Chanwan, and Kuthine populations, and returned members of the Senrian diaspora known as dekasegi. Most Senrians practice a form of Tenkyou, the country's indigenous religion, which has been highly syncretized with Zohism and Badi; noteworthy minority religions in Senria include Sotirianity and several new religious movements known collectively as sinsuukyou. The country's official language is Senrian, though Isotaman, Esamankur, and Cotratic have been accorded limited recognition at the local level.

Senria is formally established as a unitary parliamentary republic, with legislative power vested in an elected unicameral National Assembly and executive power held by a Prime Minister designated by the legislature. While nominally a multi-party democracy, Senria has been dominated politically by the Aikokutou since 1927, and is typically classed as a dominant-party state or a Southern democracy by analysts. Senria's current prime minister is Reika Okura, the first woman to hold the office, who has held the position since 2018. Traditionally split into 21 traditional regions, the country is formally divided into 64 prefectures, which hold relatively little autonomy. The Senrian military, known as the Senrian Republican Armed Forces, consists of the Senrian Republican Army, Navy, and Air Force, and is regarded as among the foremost militaries in Coius, backed by one of the largest military budgets in the world. Senria is one of the seven states permitted to have nuclear weapons under the Treaty of Shanbally.

Senria has the second-largest economy in the world in terms of nominal GDP. A leading industrial power and major exporter of consumer goods, its economy has steadily become progressively more white-collar since the 1980s, though this has been increasingly marred by economic stagnation in the past five years. The Senrian economy is marked by the domination of a handful of corporate cliques known as keiretu and an emphasis on lifetime employment and seniority-based advancement in the corporate world. While it ranks highly on the Human Development Index, the country also suffers from high levels of income inequality. Senria's currency is the yen.

Senrian culture stands as one of the most prominent and influential cultures in the modern world, having obtained global reach during the 20th century, particularly following the start of the Senrian Wave in the 1980s. Senrian art, cinema, cuisine, literature, music, television, and video games are well-known and capable of exercising worldwide influence, and are regarded by many analysts as an important facet of Senrian soft power.

Senria is commonly considered one of the world's great powers due to its large population, substantial military, nuclear arsenal, high standard of living, and economic and cultural clout. It holds a permanent seat on the Community of Nations's Security Committee, is a prominent member of GIFA, the AEDC, and the ITO, and plays a leading role in SAMSO, COMDEV, and the BCO.

Etymology

The typical name for Senria in the Senrian language, written in Gyoumon as 千龍國 or 千竜国 and in Kokumon as 썬류우꼬꾸, is pronounced Senryuukoku.[8] This name, sometimes clipped to Senryuu, roughly translates as "country of a thousand dragons". It is widely agreed that this name is derived from a traditional legend claiming that the Senrian people are descended from a woman named Toyomike and the kami Pairyuu, typically depicted as a dragon, disguised in human form.[9][10] The first confirmed use of the term to refer to Senria appears in the Yiguoji, a Shangean chronicle from 372 CE;[11] claims of artifacts or manuscripts showing earlier use within Senria itself are contentious and not universally accepted by historians.[12]

The clipped form Senryuu is sometimes altered to Zensenryuu, "all Senria", or Daisenryuu, "great Senria", in poetic, literary, or patriotic contexts.[13] Senria is also sometimes poetically or euphemistically referred to as Musuuzima-no-Kuni (무쑤우시마노꾸니 in Kokumon, 無数島の国 in Gyoumon and hiragana; literally "country of countless islands"), Mizuho-no-Kuni (미수호노꾸니 in Kokumon, 瑞穗の国 in Gyoumon and hiragana; literally "country of lush ears of grain"), or Akitukuni (아끼뚜꾸니 in Kokumon, 現御国 in Gyoumon; literally "the present country" or "the country we are in").[14]

The earliest known Euclean form of the name "Senria", Tsenliong, appears in the writings of Ponte Pilote, written in Gaullican,[15] and likely derives from the Late Middle Shangean pronunciation of the characters 千龍.[16] The chronicles and letters of Luzelese and Hennish explorers in the 16th century contain several variations more obviously derived from the Senrian form of the name, including Senrijoe, Senriou, Sennrija, and Senreia; these variants rapidly supplanted the earlier Tsenliong and converged into the Gaullican Senrie, which in turn became the modern Estmerish Senria.[17]

History

Prehistory and antiquity

The first archaeological evidence of human habitation in what is now Senria are a series of human fossils found on the island of Iezima, believed to be roughly 32,000 years old.[18] Paleolithic archaeological sites in Senria are often small and fragmentary; the comparative acidity of Senrian soil creates adverse conditions for fossilization, and many sites consist mostly or only of stone tools. Additionally, changes in sea level between the Pleistocene and Holocene likely mean that many early Paleolithic sites are now underwater.[19] However, some remarkable findings have been uncovered; notably, ground stone tools, normally not found until the Mesolithic or Neolithic, appear in Senria during the Paleolithic, far earlier than in most other places. It is unclear why this technique appeared so early in Senria.[20]

The Seidou culture, a sedentary hunter-gatherer culture emerged in Senria circa 14,000 BCE.[21] The culture, named for the village of Seidou, where artifacts from the period were discovered in 1878, is known for its "cord-marked" pottery, ornate earthenware figurines known as doguu,[22][23] and the construction of pit dwellings.[21] While there is evidence that the Seidou culture engaged in limited horticulture and arboriculture - including the cultivation of Senrian chestnuts, calabashes, adzuki beans, and lacquer trees[24] - it appears that hunting and gathering remained more important overall, enabled by the favorable conditions of the Holocene climatic optimum.[25] Middens from the period suggest a heavy reliance on fish, shellfish, and wild game. Climatic cooling disrupted this lifestyle and caused a rapid population decline, however,[26] and the Seidou archaeological sites largely disappear by 1,000 BCE.[21]

The Seidou culture was succeeded by the Sugawara culture. The advent of the Sugawara period, which lasted from roughly 1,000 BCE to 240 CE,[21] brought a slate of transformations to the Senrian archipelago. Silk making,[27] glass making,[28] bronzeworking, and, towards the end of the period, ironworking[29] all first appear in Senria during this timeframe, as do new methods of making pottery, textiles, and lacquerware.[30] Agriculture also expanded significantly, with the cultivation of rice, barley, buckwheat, soy, and millet becoming widespread;[31] in particular, the arrival of wet-field agriculture allowed for intensive rice farming and corresponding population growth.[32] The Sugawara period is also marked by the advent of increasingly complex settlements and the construction of ceremonial bronze bells known as doutaku.[28] Most archaeologists agree that the modern Senrian people are the result of genetic admixture between remnants of the Seidou people and the Sugawara people,[33] who are thought to have migrated to the archipelago from an original Senric urheimat on the Kaoming Peninsula, bringing continental technologies with them in the process.[34]

Within traditional Senrian historiography, the period from 710 BCE to 240 CE is typically referred to as the Eiken period (Kokumon: 에껀, Gyoumon: 栄剣).[35] Traditional records claim that Senria was unified by the Emperor Kousou, with the backing of the kami Pairyuu, in 710 BCE,[36] and that Kousou and his successors established several important Senrian political and cultural traditions over the next five centuries;[37] however, most historians regard these claims as myths largely unrelated to historical and archaeological fact.[38] Similarly, some Shangean works from this period - most notably the Histories of Wu Biao, written in the 100s CE - mention "lands to the west" or "islands of the sunset", ruled by shaman-monarchs and home to the elixir of life, but are regarded as too mythical to be reliable sources by most modern historians.[12]

While the archaeological record remains an important source of information, the first reliable written sources detailing Senrian history - including the Yiguoji, which contains the first confirmed reference to Senria[11] - appear during the Sunzuu period (Kokumon: 쑨수우, Gyoumon: 春秋), which lasted from 240 to 558.[37] During this period, the Senrian Empire - whatever the exact nature of its origin - cemented its rule over central Kousuu and expanded across Kousuu into Tousuu and Yuusuu, securing its rule over the three largest islands in the Senrian archipelago by the end of the 400s.[39] These early Senrian monarchs extended their rule both through warfare and by offering the leaders of local clans positions of authority in exchange for their vassalage, incorporating them into the imperial system.[40]

Characteristic to the Sunzuu period are kohun, megalithic tumuli (some up to 400 meters long)[41] which served as monumental aristocratic tombs for the clans who reaped the benefits of the early growth of the nascent Senrian state.[42] The emperors, meanwhile, demonstrated their growing authority by reconstructing Senria's capital, Heikyou, on a grid pattern resembling the one used by the Sun dynasty capital Fuzhou.[43] Growing contact between Senria and its neighbors was also a feature of the Sunzuu period. Much of this contact was mercantile or cultural in nature; however, the period also saw the Seikou War, in which the 496-503 Qing kingdom - one of the major kingdoms of Shangea's Four Kingdoms Period - launched an invasion of Senria hoping to take advantage of an ongoing dynastic dispute, only to be repelled after the dispute was resolved while the Qing army was in transit, with Senrian forces launching their own incursions into the Kaoming Peninsula in the final years of the war.

The Kaihou period (Kokumon: 깨호우, Gyoumon: 改法) lasted from 558 to 774 and saw the rising Senrian state further centralize and reshape itself. Zohism and Taoshi both arrived in Senria in the 500s and, despite initial aristocratic resistance, gained widespread acceptance due to their active promotion by figures including the Emperor Ninmyou; they would come to syncretize heavily with Tenkyou and influence Senrian law, philosophy, and theology for centuries. In the 600s, the Empress Genmei - after successfully defending her claim to the throne in the Genmei War - oversaw a sweeping series of reforms referred to as the Seitenhou Reforms. These reforms, which included equal field-style land reform, the development of a family registry system as part of tax reform, the creation of a council of state and subordinate ministries to oversee administration, and the implementation of the rituryou legal code, greatly enhanced central authority by weakening (though not fully sidelining) the noble clans in favor of a meritocratic imperial court which was able to effectively raise taxes & levies and impose its laws across the country.

The dividends of these reforms manifested in what has traditionally been considered a golden age for Senria.[44][45] The increased ability of the Senrian state to raise taxes and levies allowed it to conquer Kisima and Rousima, and to begin extending its influence into Gyousuu and the Isotama Islands. Stronger administration bolstered trade, which further increased revenue and in turn enabled patronage of the arts, resulting in an explosion of visual art, architecture, music, and literature & poetry. This flourishing became the foundation of what is now regarded as classical Senrian culture.

The administrative system created by the Seitenhou Reforms remained in place in some form, at least nominally, for roughly six hundred years; the first noteworthy changes occurred only a few decades after the original implementation of the Seitenhou system, during the reign of the Emperor Kenryaku. Notably, Kenryaku's changes included a provision permitting Tenkyou temples and Zohist shrines to avoid taxation entirely, which would have substantial impacts in the centuries to come.[45]

Feudal era

Senria's feudal period is typically held to begin with the Kingen period (Kokumon: 낀건, Gyoumon: 金絹), which lasted from 774 to 1113. During this period, the cultural golden age which began during the Kaihou period intensified, enabled by extensive patronage from the nobility. In particular, the art of the Kingen period shows an increased willingness to diverge from Shangean forms in favor of uniquely Senrian styles and techniques, influenced by a contemporaneous blossoming of vernacular culture, and the period is therefore regarded as essential in shaping the maturation of Senria's national culture. The period also saw the arrival of Badi in the 800s; while Badi did not receive official backing in the way that Zohism and Taoshi had, and therefore did not ingrain itself as widely, it nonetheless firmly established its presence within the country.

Politically, however, the Kingen period saw centralized authority begin to degrade.[45] Amendments to the Seitenhou Reforms which entirely exempted temples and shrines from taxation enabled monks to establish large estates known as souen; this empowered monks to begin seeking key government roles, akin to the sengshui system which emerged in Shangea and the Svai Empire, during the first century of the period. The rising power of the monastic class was derailed, however, once secular nobles figured out how to obtain souen recognition for their own manors; these nobles then used the wealth they obtained from their tax-free estates to purchase hereditary positions for themselves. This reduced government tax revenue and hamstrung any efforts at meritocracy. The degradation of central power was worsened by the imperial court's preoccupation with artistic pursuits, which led to the neglect of government affairs. The administration of Heikyou itself (increasingly known as Keisi by this point) increasingly became the domain of regents known as sessou, while the governance of the rest of the country became the de facto prerogative of the now-hereditary noble magnates, referred to as daimyou. While Senria, through the daimyou, was able to establish its control over Gyousuu by the end of the 9th century, the country lost control of the Isotamas and was defeated by the Tao dynasty in the 1104-1112 Toukou War, nominally ceding control of Tousuu to Shangea for roughly a century.

The degradation of central authority worsened during the subsequent Zakkoku period (Kokumon: 삮꼬꾸, Gyoumon: 弱国), which began in 1113 and ended in 1339. With imperial power collapsing and the specter of domestic & foreign threats looming, the daimyou began to turn their small private retinues into large armies of military nobles known as samurai, who were in turn bound by a moral code known as busidou. In conflicts like the 1165-1169 Zensinen War and 1244-1250 Gorokunen War, the new military aristocracy asserted its power, defeating the Keisi gentry who had monopolized power through the regency and formally entrenching their own power with a treaty known as the Golden Oath. While improvements to irrigation and double-cropping permitted increased agricultural yields and some population growth, rising instability blunted any positive developments, and efforts to reassert imperial authority - most notably the 1336-1339 Kouei War, which ended the period - were ultimately unsuccessful and only emphasized the position's powerlessness.

The abdication of the Emperor Kouei in 1339 is generally regarded as marking the start of the Tigoku period (Kokumon: 띠고꾸, Gyoumon: 血国), which lasted until 1667 and was marked by a total collapse of central authority. A string of wars between daimyou, ranging from small clashes to nationwide conflicts, caused regular turmoil, with the movement of pillaging armies leading to periodic outbreaks of famine and disease. The position of sessou was reestablished, this time as a means for daimyou to assert symbolic authority by controlling the emperor, and the Hibotu Islands were brought under Senrian control. The power of the samurai was further expanded as a result of their central importance to daimyou armies; the perpetual instability of the period and the glorification of martial life also resulted in the rise of the tankenhei, adventurers and conquerors who performed mercenary work across southern Coius. The endemic turbulence resulted in, and was exacerbated by, the spread of apocalyptic strains of Zohism among the peasantry, and was further worsened by the arrival of Sotirianity alongside Euclean merchants in the 1500s.

Anger among the peasantry at the misrule, destruction, and famine emerging from such perpetual bloodshed led to outbreak of the Kyoutoku Rebellion in 1425, the largest such revolt in Senrian history; while the revolt is typically considered to have ended in 1434 with the death of many of its leaders, most famously the rounin Hyouzaemon Nabesima, scattered groups of rebels persisted for decades. The country was invaded by the Jiao dynasty in the 1651-1655 Soukou War, with the war ending inconclusively due to the outbreak of the Red Orchid Rebellion within Shangea. An attempt by the Emperor Ninpei to revoke the Golden Oath instead plunged Senria into chaos, leading to Ninpei's forced abdication and the 1660-1667 Toukei War. At the end of the Toukei War, after more than three centuries of severe instability, the leading daimyou came to an agreement known as the Kamakura Accord, which established a balance of power between the major daimyou, replaced the regency with a body known as the Council of Seven, and banned Sotirianity.

The Kamakura Accord allowed for the restoration of peace to a fractured Senria, and marked the start of the Suikoku period (Kokumon: 쒸꼬꾸, Gyoumon: 睡国), which lasted from 1667 to 1869. In the name of keeping this fragile peace together, the daimyou rigidly maintained the balance of power among themselves and stringently suppressed social unrest and Sotirianity through the application of grievous punishments and the imposition of Neo-Taoshi thought alongside a strict caste system. Nonetheless, the return of some form of peace to the country enabled rapid agricultural, commercial, and population growth, all of which were aided by the construction of infrastructure and standardization of currency under the auspices of the Council of Seven, and by significant improvements in Senrian literacy and numeracy due to the construction of schools by the daimyou and by urban elites. Returning prosperity also enabled a renewed cultural flourishing in the fields of art, literature, poetry, and theater; these cultural developments both reshaped Senrian culture and influenced how it was perceived by Euclea over the next three centuries. Additionally, while large amounts of power remained dispersed among the daimyou, renewed internal stability allowed Senria to begin exerting some external influence again, bringing the Isotamas back into the Senrian sphere in the 1700s and formally annexing them after a brief conflict in 1820.

However, Senria - like the rest of Coius - continued to fall behind Euclea technologically during this timeframe, and was forced to accept increasing Euclean imposition in its affairs. The country was forced to cede the Far Isotamas to Estmere in 1852 and accept the establishment of a legation quarter in Keisi in 1860. To try and counter these developments, the Emperor Youzei worked to formally promote gaigaku (the study of Euclean technology and medicine) and kokugaku (the study of Senrian history and culture) with the aim of fostering Senrian unity and constructing the foundation for the country's modernization. These efforts were constrained by his limited authority and interference by the daimyou; in spite of this, by the time Youzei died in 1869 he had succesfully established a framework for the country's modernization.

Modern era

In 1869, the Emperor Youzei was succeeded by his son, the Emperor Keiou, marking the start of the Kaisei period (Kokumon: 깨쎄, Gyoumon: 回生), which lasted from 1869 to 1923. Almost immediately upon taking the throne, Keiou exploited divisions among the leading daimyou between those who opposed any Euclean influence, those who sought to preserve the status quo, and those who sought rapid Northernization to launch the Keiou Restoration. Backed by certain daimyou, and receiving military and financial assistance from Estmere and Werania, Keiou used modernized military forces to reassert imperial authority and break the power of the daimyou, establishing a renewed Senrian Empire under a semi-constitutional monarchy in which almost all power was held by the emperor, who was in turn to be advised by an elected Deliberative Assembly.

Keiou and his allies subsequently undertook a series of reforms aimed at strengthening and modernizing the country, including weakening the Suikoku-period caste system; undertaking land reform to enable private ownership and leasing; standardizing the Senrian language; permitting freedom of religion while simultaneously giving state backing to Tenkyou; modernizing the country's infrastructure, economy, government, and military; and adopting Northern clothing, science, cultural forms, and education. While these reforms were initially undertaken with great vigor, they were halted after Keiou's death by his brother, the Emperor Suizei, who was aligned more closely with traditionalists. Suizei's successor, the Emperor Tenmei, restarted the country's military reforms, but was wary of efforts at economic and social Northernization; this weakened Senria's modernization efforts and left it deeply susceptible to the negative consequences of the 1913 Great Collapse. Additionally, the loss of Sakata to Shangea in the 1909 First Sakata Incident weakened faith in the government, and Tenmei's authoritarian tendencies led him to try realigning the country towards Gaullica, which angered Estmere and Werania.

Public anger at the protracted economic crisis and political repression led to the outbreak of the Senrian Revolution in 1918. While republican revolutionaries, led by Ryuunosuke Miyamoto politically and Souzirou Okada militarily, were able to take control of much of the country's west, imperial forces were better-trained and better-equipped than their republican counterparts, and won several victories during the initial year of the war. The imperial position weakened substantially following the assassination of the Emperor Tenmei, however, as his successor Souhou interfered in military affairs and mismanaged the war effort. The 1923 Great Kinkeidou Earthquake devastated Keisi and further weakened the imperial position, and as republican forces - now led by Miyamoto's protégé Isao Isiyama and receiving assistance from Estmere and Werania - gained the upper hand, dissent grew in the armed forces. A group of generals and admirals, known as the Gang of Six and led by Katurou Imahara, launched a military coup against the Emperor Souhou in November 1923, capturing him and forcing the abolition of the monarchy; a subsequent power-sharing agreement between Isiyama and Imahara ended the revolution shortly thereafter.

The overthrow of the monarchy began what is sometimes known as the Kyouwa period (Kokumon: 꾜우외, Gyoumon: 共和), which continues into the present. The period immediately following the Senrian Revolution saw a remarkable cultural renaissance and several efforts by Isiyama's government to effect social reforms, most notably its successful abolition of the remnants of Senria's caste system. This brief flourishing, however, was brought to a halt by the 1927 Shangean invasion of Senria, which marked the beginning of the Great War. Shangean forces, aided by monarchist & functionalist collaborators, sought to force Senria under Shangean rule and conducted the Senrian Genocide, in which 9.5 million Senrians were murdered as part of a campaign of systemic extermination. Katurou Imahara used the crisis to establish himself as the head of a "government of national preservation", assuring Isiyama that he would relinquish dictatorial power after the Shangean invasion was repelled.

Imahara implemented a three-point program of "mass production, mass industrialization, and mass mobilization" to build up Senria's industry and military for total war,[46] which in turn allowed Senrian forces to halt the advance of Shangean forces; the Government of National Preservation also aided the Senrian Resistance, which conducted sabotage and guerrilla operations against Shangean and collaborationist forces to great effect. The Ukyou Uprising ended any Shangean hopes of launching further offensives in Senria, and Shangean forces were expelled from the Senrian archipelago on June 16, 1932; Senria launched its own invasion of Shangea, marked by a brutality regarded as "retaliation" for the Senrian Genocide, the following year. While Senria initially sought Shangea's total surrender and dismemberment, domestic war-weariness and pressure from its Euclean allies forced Senria to end the conflict on February 12, 1935, with the Treaty of Keisi being signed that April.

While Imahara did concede absolute power as promised and include Isiyama and the Kyouwakai in the negotiations which led to the country's current constitution, which de jure established Senria as a parliamentary republic, Imahara used his public popularity and his control over the military to centralize power in himself, the Aikokutou, and the Senrian Republican Armed Forces. As Prime Minister, Imahara implemented his personal ideology as state doctrine and oversaw a series of sweeping reforms, continuing the country's military modernization, overseeing a period of rapid economic development known as the Keizaikiseki, expanding rights for women and burakumin, ending the concessions granted to Euclean powers, replacing Gyoumon characters with the Kokumon script, bolstering Senrian nationalism, and stringently controlling political dissent. He also sought to secure Senria's position as a world power and as the leading nation in Coius, providing extensive support to the Community of Nations.

Imahara was succeeded by Hatirou Nakayama, who was in turn quickly replaced by Tokiyasu Kitamura. Kitamura sought to shift the center of power in Senria's government from the military towards the Aikokutou, and oversaw an economic and cultural flourishing, as well as efforts to establish a détente with Shangea. Assassinated by a councilist in 1964, he was succeeded by Takesi Takahata, who restored military primacy, cracked down on dissent, and oversaw a more aggressive foreign policy in the name of maintaining Senrian preeminence in Coius; Senria developed nuclear weapons during Takahata's premiership, and the country nearly went to war with Shangea in the 1975 Coastal Crisis. After Takahata was assassinated by Shangea in 1979, he was succeeded by Imahara's adopted son Kitirou, who was forced from power himself due to his inability to handle the fallout of the 1979 Coian economic crisis.

Kitirou Imahara was replaced by Kiyosi Haruna in 1983. Haruna successfully addressed the country's economic crisis by brokering an agreement between the major keiretu and depoliticized the country's military, firmly shifting power to the bureaucracy and Aikokutou. He also ended government censorship of the media, loosened restrictions on opposition groups and civil society (but guaranteed the continued preeminence of the Aikokutou), responded to the 1995 Kinkeidou Earthquake, engaged in both hardline and pragmatic diplomacy with an increasingly resurgent Shangea, and oversaw the start of a global popularization of Senrian culture known as the Senrian Wave; Haruna left office in 2003 as Senria's longest-serving prime minister. In the decades since, Senria has remained a dominant-party Southern democracy, and while its growth has slowed, it continues to be a leading economic, cultural, and military power within both Coius and the world.

Geography

Senria comprises 6,884 islands and islets located to the south and west of Coius. The main portion of the country, the Senrian archipelago, is a stratovolcanic archipelago bordered by the Lumine Ocean to the west and north, the Bay of Bashurat to the northeast, the Rangyoku Strait to the east, and the Honghai Sea to the south and southeast. The four "main islands" of the Senrian archipelago, from east to west, are Tousuu, Kousuu, Yuusuu, and Gyousuu. Smaller islands within the Senrian archipelago include Kisima and Rousima, located north of Yuusuu and west of Kousuu; Kanasima, south of Kousuu; Sugisima, north of Kousuu; and Kaedezima, located between Yuusuu and Gyousuu. Within the larger Senrian archipelago, two subarchipelagos are typically identified - the Isotama Islands, to the northeast of the main islands, and the Hibotu Islands, the westernmost portion of the country. The archipelago also contains several thousand smaller islands and islets, of which about 520 are inhabited.

The Senrian archipelago stretches roughly 2,554 kilometers (1,587 miles) in length, but is comparatively narrow, only about 460 kilometers (285 miles) wide at its widest point, and no point in the archipelago is more than 158 kilometers (98 miles) away from the ocean. Most of the archipelago's terrain is highly mountainous, and, because of this, more than 65% of it is uninhabitable. As a result, the habitable areas - located primarily in coastal regions - are very heavily populated, giving Senria one of the highest population densities in the world, and most land which is suitable for development is in use. Land reclamation has been used to expand the amount of land available for human use, particularly in the years since the end of the Great War; roughly 0.6% of the country's total area is reclaimed land as of 2018. Senria's mountainous terrain also means it has few navigable rivers, though extensive coastal shipping, particularly within the Bay of Hisui, the Nangyoku and Ransou inland seas, and the Kahoumon and Toyozimon straits, compensates for this.

Because of its location along the boundary of the Lumine and Austral tectonic plates, the Senrian archipelago is significantly prone to earthquakes, volcanic activity, and tsunamis. The country has 117 active volcanoes, including three VEI-7 volcanoes and two Decade Volcanoes. Major seismic events, meanwhile, occur within Senria several times each century; the 1923 Great Kinkeidou earthquake killed between 100,000 and 150,000 people, while the 1982 Taiseiyou earthquake caused a tsunami with a maximum run-up height of roughly 10 meters (32 feet), though it caused only 104 fatalities.

Senria also controls the Sunahama Islands, a chain of twenty-eight atolls and islets located on the border of the Honghai and Coral seas. Of these, nineteen atolls are inhabited, while the other nine are uninhabited, either because of environmental factors such as a lack of fresh water or due to contamination from Senrian weapons testing. Obtained from Gaullica following the end of the Great War, the Sunahamas are also claimed by Shangea.

Senria has a total area of 609,136.64 km2 (235,189 sq mi); metropolitan Senria has an area of 589,191.68 km2 (227,488 sq mi) while the Sunahamas have an area of 19,944.96 km2 (7,701 sq mi). The Senrian archipelago lies roughly between latitudes 18° and 33°S and longitudes 146°W and 180°E; the Sunahamas are located roughly between latitudes 44° and 48°S and longitudes 105° to 115°W. The country's highest point is the peak of Mount Senzou, which stands 3,776 meters (12,388 feet) tall; its lowest natural point is Lake Notorigata, a now-partially-reclaimed lagoon located 4 meters (13 feet) below sea level. As an island nation, Senria has no land borders; however, it does share a sea border with Shangea in the Rangyoku Strait.

Islets on the northern coast of the Nangyoku Inland Sea.

Snow-capped mountains in the Senrian Aventines.

Forest and farmland in central Gyousuu.

The Agano River flowing through Nisiyama.

Lake Kimun, a crater lake in Yuusuu.

Climate

The majority of Senria has a temperate climate falling into the Köppen system categories Cfa (humid subtropical climate) or Cfb (temperate oceanic climate); however, some of the southerly regions of the archipelago have continental climates, primarily Dfa (hot-summer humid continental climate) or Dfb (warm-summer humid continental climate). Aventine climates can also be found in parts of Senria on account of its pronounced topography.

The country is generally rainy, though its many mountain ranges mean that parts of the country's east are affected by rain shadows and foehn winds, though these areas are still relatively wet, receiving at least 750 millimeters (30 inches) of rain annually; much of the country sees heavy snowfall during the winter. As a result of the country's heavy rainfall, sunshine is generally modest in quantity. Much of western Senria is at risk of typhoons during the mid-to-late summer and early fall; an average of five or six typhoons pass over the country annually.

Biodiversity

Senria is the native home of between 4,000 and 6,000 species of plant. The country's north is dominated by a mixture of both deciduous and evergreen broad-leaved trees such as the Senrian elm, spotted laurel, keyaki, Senrian beech, sakaki, Senrian evergreen oak, and Shangean ring-cupped oak. At higher altitudes and in the country's south, by contrast, forests are dominated more by conifers including the hinoki cypress, southern Senrian hemlock, Senrian cedar, Yuusuu spruce, Senrian red pine, and Senrian black pine. The country's national tree is the Senrian maple. Flowering and fruiting plants native to Senria include plums, cherries, chestnuts, azaleas, camellias, wisterias, irises and chrysanthemums. Important or famous food crops originating in Senria include the adzuki vine, water celery, wasabi, and edible seaweeds such as nori and hiziki; the country is also famous for its edible mushrooms, such as the highly-prized siitake and matutake mushrooms.

The country also exhibits great diversity in animal life. Mammal species native to Senria include the Yuusuu brown bear, red fox, tanuki, Senrian marten, Steller's sea lion, sika deer, Senrian serow, Isotama flying fox, and Senrian macaque. Native species of bird include the golden eagle, Senrian sparrowhawk, Blakiston's fish owl, red-crowned crane, Senrian woodpecker, green pheasant, Austral turtledove, and Senrian quail. Reptiles native to Senria include the loggerhead sea turtle, Senrian pond turtle, Shangean sea snake, Isotaman habu, Senrian pit viper, Isigaki's odd-scaled snake, and common lizard. Senria is home to at least forty species of amphibian; the most famous of these is the Senrian giant salamander, the third-largest species of salamander in the world. With regards to insects, Senria has more than 300 species of butterfly, more than 1,000 species of moth, and 190 species of dragonfly; the country is also known for its cicadas, fireflies, crickets, and hornets. Senria is home to more than 3,000 species of fish, including the ayu, common carp, cherry salmon, Senrian taimen, red seabream, whitespotted conger, Lumine saury, Lumine bluefin tuna, and Senrian sea bass.

Environment

Senria suffered severe environmental degradation between the 1930s and 1970s, with environmental concerns downplayed by the Senrian government in favor of an emphasis on rapid industrialization and maximizing economic growth. This had serious consequences, both for the integrity of the environment and public health. Between the 1950s and 1970s, improper handling of industrial waste by Senrian corporations and chemical contamination resulting from unsafe working conditions, corporate error, or deliberate adulteration caused a spate of man-made diseases and mass poisonings popularly known as the Six Big Man-made Diseases - cadmium poisoning, methylmercury poisoning, sulfur dioxide poisoning, arsenic poisoning, diethylene glycol poisoning, and polychlorinated biphenyl poisoning. In response to increasingly widespread public anger, efforts to address the issue were made by the government of Tokiyasu Kitamura through legislation and court action in the early 1960s, but many of these measures lapsed or were overturned during the subsequent government of Takesi Takahata. A renewed push for environmental protection legislation occurred in the 1980s, and several laws aimed at limiting pollution, protecting consumers, and expanding Senria's national park system were passed with the assent of Prime Minister Kiyosi Haruna; these laws served as the basis for stricter legislation passed during the premiership of Sigesato Izumi.

Nonetheless, several issues persist. Air pollution remains a serious problem in Senria, particularly photochemical smog caused by industrial fumes, vehicular emissions, and the incineration of garbage. Senria is a major consumer of fossil fuels; in 2017, roughly 85% of the country's electricity production came from coal, oil, or natural gas. This use of fossil fuels contributes both to the country's own air pollution and to global climate change. While strict standards for the cleanliness of drinking water and treated wastewater have been successfully implemented, water pollution is still a persistent issue, with the damage to aquatic ecosystems being compounded by overfishing, eutrophication, algal blooms, and the destruction of coastal ecosystems by land reclamation efforts. Environmental watchdog groups have alleged that the country's environmental regulations have been poorly and inconsistently enforced by the governments of Hayato Nisimura and Reika Okura. The continued practice of whaling, defended by the Senrian government as a scientific necessity and a cultural tradition, is a source of international controversy. Senria's government has also been accused of participating in and funding the denial of climate change.

The Senrian government has responded to criticism by claiming that the critiques put forward by environmentalists exaggerate the scale of environmental issues within the country, insisting that Senrian environmental protection legislation is strictly enforced and alleging that claims to the contrary are invented or amplified by bad faith actors, particularly the government of Shangea. It has also pointed to the funding put by both the Senrian government and Senrian companies into green technology. Since 2010, the government has also overseen reforestation campaigns aimed at restoring local environments and preventing erosion.

Politics

Governance

Senria is legally established as a unitary parliamentary republic and, accordingly, the country is sometimes characterized as the most populous democracy in the world. The Republic of Senria was originally formed in 1918, following the start of the Senrian Revolution; however, the country's current constitution was not written until 1933. In practice, Senria is often characterized as a dominant-party state or as a Southern democracy as a result of the longstanding preeminence of the Aikokutou, which has ruled the country in some form since 1927.

Senria's legislature, the National Assembly, is a unicameral parliament which consists of 545 members who are directly elected for single-member districts every five years. These elections use a first-past-the-post plurality voting system. The day-to-day operation of the National Assembly is handled by the Chairman of the National Assembly, elected by the National Assembly from among its membership; the chairmanship is currently held by Seitarou Nakagawa, who was first elected to the position in 2013. Thirteen political parties are currently represented in the National Assembly; three of these - the Aikokutou, Justice Party, and Reimeisa - form a political alliance known as the Kokuminsa, the country's governing coalition, de facto dominated by the Aikokutou.

The National Assembly also selects the Prime Minister of Senria, who is traditionally the leader of the largest party within the legislature. The premiership of Senria is unique in that the Prime Minister is both head of government and head of state, instead of being only the former; this differentiates Senria from most other parliamentary republics and emerged as a result of the negotiations that surrounded the drafting of the country's constitution. They are also the country's chief executive and the commander in chief of the Senrian Republican Armed Forces, and appoint the members of the Cabinet of Senria. After being approved by a majority vote of the National Assembly, the Prime Minister holds the position for the remainder of the National Assembly's term, unless removed from office early by resignation, death, or a motion of no confidence. Senria's current prime minister is Reika Okura of the Aikokutou, the ninth person and first woman to hold the office, elected to the position following the 2018 Senrian general election.

While Senria's legal system was historically heavily influenced by a mixture of Shangean law and local traditions, the modern Senrian legal system - following the Keiou Restoration and the Senrian Revolution - is primarily based upon Euclean civil law. The primary body of Senrian law is known as the Six Codes, consisting of the country's constitution, civil code, code of civil procedure, criminal code, code of criminal procedure, and commercial code. The Senrian judiciary has four levels of court: summary courts, district courts, high courts, and the Supreme Court of Senria. The judiciary is constitutionally established as independent from the executive and the legislature and the Supreme Court is accorded some powers of judicial review. Judges, including supreme court justices, are nominated by the prime minister and confirmed by a majority vote in the national assembly, holding office until their resignation or death.

While Senria has universal suffrage for all adults over eighteen years of age, the secret ballot, and certain constitutional safeguards for civil and political rights, it also has a long contemporary history of authoritarian rule and is regarded by many scholars as an illiberal or Southern democracy. Most of Senria's prime ministers before 1983 were de facto military dictators who tightly controlled political life and used the Aikokutou as a means of mass mobilization and to provide their rule with a veneer of legitimacy; while civilian control of the military was entrenched in the 1980s and 1990s by the government of Kiyosi Haruna, who also oversaw a period of political liberalization, Senria continues to be a dominant-party state in which power is concentrated in the leadership of the Aikokutou. The country has a mixed record on freedom of speech, with dissidents and opposition figures sometimes facing legal or extralegal harassment, and freedom of the press is de facto limited as a result of close ties between the government and much of the Senrian media. Corruption is endemic within the upper levels of Senrian governance, though corrupt behavior at the lower levels is routinely punished; Senrian politics are also marked by nepotism and cronyism, and these features, combined with the role that the Aikokutou has played in shaping the makeup of Senria's bureaucracy and judiciary and the Aikokutou's close ties to Senria's keiretu and alleged ties to certain yakuza groups, have led some observers to argue that Senria has a nationalistic, illiberal deep state. The Senrian government has largely rejected criticism that it is illiberal or undemocratic, arguing that Senria is "a democratic republic in line with Imaharist doctrine" and claiming that negative reports on human and civil rights in Senria "routinely contain serious misrepresentations and factual errors".

Administrative divisions

Senria is divided into sixty-four prefectures (Senrian: 껀, ken; Gyoumon: 県). Each prefecture is run by a governor and a unicameral prefectural assembly, both directly elected every five years. Prefectural governments are tasked with the organization of schools and hospitals, maintaining infrastructure and managing urban planning, handling administrative affairs, and overseeing local emergency services, including the local branches of the National Police. Prefectures also have a limited ability to pass local regulations and ordinances. However, as Senria is a unitary state, this authority is limited; there must be a national statutory basis for local ordinances, and local ordinances are forbidden from having penalties greater than two years in prison and a fine of ¥1 million. The autonomy of prefectures is further limited by the fact that prefectures are only permitted to operate autonomously within the often-tight framework established by national law, and by the financial dependence of prefectures upon the central government.

Prefectures are further subdivided into municipalities. Municipalities compile the koseki and zuuminhyou civil registries and assist prefectures in organizing the provision of public services. Senrian law establishes three types of municipality: cities (씨, si; 市), towns (마띠, mati; 町), and villages (무라, mura; 村). Cities are divided into a further set of categories based on population; larger cities are granted greater autonomy and authority, sometimes approaching the authority accorded to prefectural governments, and the ability to subdivide themselves into wards (꾸, ku; 区). Towns and villages have little autonomy but are permitted to govern themselves by a general assembly of citizens as opposed to a mayor-council system.

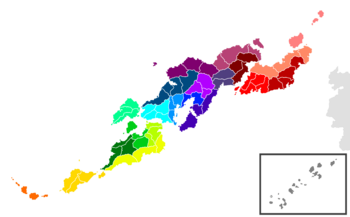

Traditional regions

Traditionally, Senria was divided into twenty-one regions (띠호우, tihou; 地方) or circuits (도우, dou; 道), which were further subdivided into districts (군, gun; 郡); these regions and districts were the country's de jure administrative subdivisions throughout the classical, medieval, and early modern periods, though in practice they were often overshadowed or superseded by the private estates of daimyou (한, han; 藩). Senrian emperors would regularly legitimize the authority of certain powerful daimyou by granting them symbolic dominion over the region where their domains were located.

Han were abolished following the Keiou Restoration, and both the traditional regions and districts were formally dissolved following the Senrian Revolution; as a result, these historic divisions retain no official status or function within contemporary Senria. In practice, however, the country's traditional regions are at times used for statistical purposes by both private and public groups, and they sometimes appear in geography textbooks, maps, and weather reports. Additionally, some government offices organize their geographical subdivisions to correspond with traditional regions, and many private businesses and institutions include their "home region" within their name. They also retain a degree of cultural relevance, with certain traditional regions being associated with certain stereotypes.

Foreign relations

Senria is a founding member of the Community of Nations and serves as one of the permanent members of the Community of Nations Security Committee; the Senrian language is one of the official languages of the CN. Senria is a prominent member of the Global Institute for Fiscal Affairs, International Trade Organization, and Association for Economic Development and Cooperation, and the leading power behind the Sangang Mutual Security Organization, Bashurat Cooperation Organization, and Council for Mutual Development. The country also has warm ties with, but is not an official member or observer of, the Euclean Community and the North Vehemens Organization. On account of its large population, economic and military power, and global cultural clout, many observers have labelled Senria as a potential superpower. The country's foreign affairs are handled by the Ministry of Rites.

Senria is generally regarded as having warm relations with the leading countries of the Euclean Community. The country has longstanding diplomatic ties, dating back to the Senrian Revolution and the Great War, with Werania and with Estmere, sometimes considered to be Senria's "traditional allies". Senro-Estmerish relations are particularly close; Senria and Estmere are sometimes regarded as having a "special relationship" on account of their warm diplomatic relations over the past 150 years. Senria's relationship with Gaullica is not as strong, Gaullica having historically been an ally of Shangea, but the relationship between the two is typically cordial in the present day. Outside of the Euclean Community, Senria has a longstanding relationship with Etruria; this relationship is commonly regarded as having grown increasingly close since the rise of the Tribune Movement in Etruria as a result of ideological similarities between the Tribunes and Aikokutou. The country is also a part of the "Translumine Triangle", or "Three Ss", alongside Soravia and Satucin. These relationships with Euclean and Asterian nations are important for Senria not only politically, but also economically; many of these countries serve as important markets for Senrian-made goods and products. On account of the importance of exports to the Senrian economy, Senria tends to pursue free trade on the global stage.

Through SAMSO, the BCO, and COMDEV, Senria has close diplomatic, economic, cultural, and military ties with many countries in Coius. Ansan is sometimes considered "Senria's closest Coian ally", the two nations having been closely aligned since Ansan's independence from Gaullica. Since the Shangean invasion of Kuthina in 2007, Senro-Kuthine ties have become increasingly close. Senria is politically and economically involved in Satria, where it has attempted largely unsuccessfully to initiate negotiations between Arthasthan and Padaratha over the issue of Minkathala, and has played an increasingly large role in Bahia in recent years, with Senria providing substantial development aid either directly or through COMDEV and Senrian companies increasingly outsourcing manufacturing jobs to Bahia as Senria shifts more towards the service sector.

Senria's relationship with Shangea is its most ancient, complicated, and acrimonious. Senro-Shangean relations have generally been hostile since the 1860s, and both Senria and Shangea regard the containment of the other as a geopolitical priority; SAMSO, the BCO, and COMDEV are widely regarded as rivals or competitors to the Shangean-dominated Rongzhuo Strategic Protocol Organization and International Forum for Developing States. Causes for Senro-Shangean enmity include geopolitical rivalry for hegemony in southern Coius, economic competition, the unilateral abrogation of the Treaty of Keisi by Shangea, and Shangean denialism of the Senrian Genocide. The two countries are also engaged in a territorial dispute over the Sunahama Islands, claimed by Shangea as the "Haishe Islands". While there have been efforts to promote bilateral negotiation between the countries, most notably the Nuclear Arms Limitation and Non-proliferation Talks, these efforts have stalled in the past decade. Similarly, Senria tends to have poor relations with countries that are regarded as Shangean allies, such as the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics and Ajahadya, though these relations are not as uniformly hostile, and certain Senrian administrations have attempted to "pry away" these nations from Shangea, with little success.

Relations between Senria and socialist nations (such as Kirenia and Dezevau) and organizations (such as the Association for International Socialism and Mutual Assistance Organisation) are generally tepid at best on account of economic and ideological differences. However, there are some socialist countries in Senria's diplomatic orbit, most notably Arthasthan, and Senrian governments have generally placed a greater focus upon opposing Shangea and Shangean influence than containing socialism.

Military, intelligence, and law enforcement

Longstanding Senro-Shangean tensions have prompted to Senria to allocate substantial attention to the Senrian military, known as the Senrian Republican Armed Forces or Senkyougun, which is one of the largest and best-funded standing militaries in the world as a result. The Senrian Republican Armed Forces consists of three branches: the Senrian Republican Army, Senrian Republican Navy, and Senrian Republican Air Force; the country's navy and air force in particular are among the country's most important tools of power projection. The Senrian military engages in technology and intelligence sharing with its military allies in the Sangang Mutual Security Organization, and the Senrian military operates deployments in other SAMSO member states.

The Ministry of Defense handles the day-to-day operation of the army while the prime minister serves as the formal commander in chief of the armed forces; both the minister of defense and prime minister are advised by the military's chief of staff. Senrian law permits the conscription of all male citizens between ages 16 and 32; however, as of 2021, the Senrian military operates as a all-volunteer force.

Senria possesses nuclear weapons and is one of the world's nine nuclear states, operating a full nuclear triad structure. The country first successfully tested a nuclear bomb in 1964. Senria is a signatory of the Treaty of Shanbally and one of the seven nations authorized by the treaty to maintain a nuclear arsenal. The Senrian government and military insist that the country does not maintain any stockpiles of biological or chemical weapons, in accordance with international law, though some international analysts have argued that Senria is likely maintaining such arsenals, or the ability to quickly establish them in wartime, in secret.

Domestic law enforcement in Senria is primarily handled by the National Police Agency, or Keisatutou, and its network of prefectural police bureaus. The Keisatutou cooperates heavily with the Public Safety Bureau, which oversees various matters of public safety such as emergency services and disaster preparedness & management; the Customs and Tariffs Bureau, the country's border control agency; and the Senria Coast Guard, which handles maritime security and search and rescue.

Senria's primary intelligence agency is the Special Police Corps, commonly referred to as the Tokkeitai. The Tokkeitai hold purview over both domestic and foreign intelligence, and historically also functioned as the country's secret police. Other Senrian intelligence agencies include the Military Intelligence Corps, or Gunzoutai, which has divisions in each branch of the Senrian armed forces and handles military and signals intelligence; the Security Bureau, part of the National Police Agency, specialized in counter-intelligence, counter-terrorism, and responding to cybercrime; and the Cabinet Research Office, a comparatively small agency which answers directly to the prime minister.

Economy

With a nominal GDP of $4.484 trillion and a GDP PPP of $9.747 trillion, Senria is the second largest economy in the world as of 2015, behind Shangea and ahead of Gaullica. The country has a Human Development Index score of .863 and a Gini coefficient of 42.1, reflecting a high standard of living coupled with pronounced income inequality. The country had an unemployment rate of 5.3%, with unemployment among 15-to-24-year-olds at 11.4%, as of the fourth quarter of 2020. In 2015, 4.1% of the Senrian labor force was employed in agriculture, 33.6% were employed in manufacturing and industry, and 62.3% were employed in the service sector. The country, one of the world's largest manufacturing economies and consumer markets, is both a major importer and exporter of goods; the country usually runs a trade surplus.

Senria has a market economy, and is variously classed as either an emerging, middle-income, or developed country, depending on the exact definition and metrics used for classification. Senria's economy is marked by the dominance of a handful of major corporate conglomerates known as keiretu, which have close, and often corrupt, relations with the Senrian government; Senrian capitalism is also notable for its emphasis on simultaneous recruitment of graduates, lifetime employment, seniority in promotions, and extreme working hours. While Senria's economy is generally strong, its growth has steadily slowed since the turn of the century; some areas of the country have struggled with deindustrialization as the Senrian service sector becomes increasingly important and manufacturing jobs are outsourced, and many analysts believe the country risks falling into the middle income trap. The difficulties associated with Senrian economic conditions, alongside endemic social and economic inequality, have led to the emergence of the so-called "Give-up Generation" among young Senrians.

Senria's currency is the yen, which is among the most traded currencies in the foreign exchange market and a major reserve currency. Its central bank is the Bank of Senria, sometimes referred to as the Sengin for short.

Agriculture and fishery

The Senrian agricultural sector employs about 4 percent of the Senrian workforce and represents roughly 1.4% of the country's gross domestic product. Senrian agriculture is limited by the country's mountainous terrain and extreme urbanization, which limits the amount of land available for cultivation to only about 20% of Senria's land area; as a result, practices such as terracing, multicropping, intercropping, and intensive farming are used to maximize the output of what arable land Senria has. These practices mean that Senria has very high crop yields per unit area. For largely the same reasons, Senria's agricultural sector is heavily protected and subsidized.

Agriculture once dominated the Senrian economy; farming accounted for 80% of the country's employment in 1870, and between 45 and 50 percent of Senrian households made a living from farming in 1925. However, the economic importance of agriculture declined precipitously throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, with farming families largely turning to nonfarming activities or moving into the country's rapidly growing cities to seek higher-paying industrial jobs. This decline in family farming has seen a corresponding rise in factory farming by agribusinesses, though family farms continue to compose a majority of Senrian farms.

Staple crop production in Senria is dominated by rice, which represents a supermajority of the country's cereal production; other important cereal crops include soybeans, wheat, barley, and buckwheat. Senria is also a noteworthy producer of tea, sugar beets, cabbage, onions, peas, eggplants, adzuki beans, persimmons, tangerines, apples, cherries, plums, peaches, and melons. The raising of livestock is a relatively minor activity, on account both of the country's limited arable land and a traditional cultural aversion to animal slaughtering as "unclean", though these norms have largely broken down in the past 150 years. Poultry forms the bulk of Senria's non-fish meat production, followed by pork and beef.

Fishery and aquaculture are important to Senria both economically and culturally. Senria maintains one of the world's largest fishing fleets and accounts for nearly a fifth of the global catch; freshwater fishing and aquaculture represents about 30% of the country's fishing industry, with saltwater fishing and aquaculture comprising the remainder. Important species of fish and shellfish caught or raised in Senria include tuna, salmon, mackerel, pollock, amberjack, sardines, clams, crabs, shrimp, squid, and octopi. Senria's fishing industry is internationally controversial; its scale has sparked concerns of overfishing, particularly of endangered species, and the continued practice of whaling has drawn the ire of environmentalist groups.

Mining and forestry

Mining is an insignificant sector of the Senrian economy, as the Senrian archipelago has very little in the way of mineral deposits. The country has some deposits of iron, copper, gold, and silver, as well as coal and oil, but none of these are particularly significant. Senria is, however, a leading producer of iodine, bismuth, sulfur, and gypsum. Surveying efforts suggest that the country's seabed could potentially contain large deposits of rare-earth elements and methane clathrate, though these deposits are not easily exploitable with current technology.

Senria's forestry sector is limited in size, even though much of the country is forested, on account of the country's rough terrain; forestry comprises only 0.04% of Senria's gross domestic product as of 2015. Nonetheless, Senrian tree farms grow a variety of trees for lumber, including cedar, cypress, spruce, and both red and black pine.

Industry

Industry accounts for 43.9% of Senria's gross domestic product and employs 33.6% of the Senrian workforce; the country's manufacturing output is one of the highest in the world. Senrian industry is concentrated in several locations, with the greater metropolitan areas of Keisi, Tosei, Isikawa, Ubeyama, Nisiyama, and Ukyou all serving as major industrial centers and strings of smaller industrial towns existing on the routes between these major cities. While efforts at industrialization began following the Keiou Restoration, it was ultimately during and after the Great War that the country industrialized, becoming a major industrial power during the postwar period; this industrial boom was the backbone of the Keizaikiseki, the country's postwar economic miracle.

Senrian industry is largely dependent on imported raw materials and fuels on account of Senria's limited mineral resources; it is also regarded as being particularly high-tech, making use of technologically advanced manufacturing techniques. In the past 20 years, an increasing number of Senrian industrial jobs - particularly low-skill jobs - have been outsourced as the country's service sector becomes increasingly prominent. Nonetheless, Senria's manufacturing and industrial sector remains large and highly diversified; key export industries include automobiles, computers, consumer electronics, semiconductors, machinery, metallurgy (particularly the refining of copper and the production of steel), chemicals, arms and armaments, shipbuilding, aerospace, pharmaceuticals, textiles and garments, and food processing.

Services and commerce

Senria's service industries are a major contributor to the national economy, representing 54.7% of the country's gross domestic product, and are the country's fastest-growing economic sector; the service sector as a whole now employs more than sixty percent of the Senrian workforce. Wholesale and retail trade are largely dominant in this area; however, Senria also has substantial advertising, data processing, information technology, real estate, and leisure industries. During the early and mid-20th centuries, these sectors - particularly retail - were largely dominated by small businesses, but globalization, rising land prices, and government collaboration with the keiretu resulted in the steady decline of these small businesses, with "waves" of consolidation occurring in the 1960s and 1980s-1990s. This tendency also intensified in the aftermath of the 2005 global economic crisis, which larger businesses weathered more successfully.

The Senrian financial sector is one of the country's largest and most profitable economic sectors. Keisi is Senria's financial center and one of the leading financial centers in southern Coius, rivalled only by Jindao; the Keisi Stock Exchange is among the largest stock exchanges in the world by market capitalization, listing more than 2,300 companies, and the Senkei Stock Average, or Senkei 300, is one of the most important stock market indices globally. Other major stock exchanges in Senria include the Tosei Stock Exchange, Isikawa Stock Exchange, Ueda Stock Exchange, and Ukyou Securities Exchange.

Senria's financial services sector encompasses several major banks, insurance companies, accounting companies, investment funds, brokerage firms, credit bureaus, holding companies, and foreign exchange companies. Senria's government charters and operates the country's central bank, the Bank of Senria, and the Senria Post Bank, which exist alongside several major private commercial banks.

The Senrian banking system is typically regarded as uniquely stable on account of the close ties between the country's major corporate conglomerates, which create a "support structure" that minimizes the risk of any member of the system going under through the joint management of liquidity and risk to assets or liabilities. However, some foreign analysts have cautioned that this risks creating a situation in which, should a severe economic crisis emerge, the entirety of the Senrian financial sector would function as a singular "too big to fail" entity, with potentially catastrophic consequences should it go under.

Infrastructure

Media and telecommunications

Senria has six major national daily newspapers - the Mainiti Sinbun, Tuusen Sinbun, Kokki Sinbun, Senkei Sinbun, Kyouwa Sinbun, and Senkan Sinbun. The Mainiti Sinbun and Tuusen Sinbun are typically classed as conservative, the Kokki Sinbun as right-wing nationalist, the Senkei Sinbun as economically liberal, and the Kyouwa Sinbun and Senkan Sinbun as center-left to left-wing. The Mainiti Sinbun is also typically considered to be Senria's newspaper of record. The country also has a variety of regional and local papers including the Keisi Sinbun, Tosei Sinbun, Nisisenryuu Sinbun, and Tousuu Sinbun. Foreign language newspapers published in Senria include the Estmerish-language Senria Daily Post & Senria Today and the Gaullican-language Courrier de Keisi. Magazines in Senria are typically divided between weekly magazines, or suukansi, and monthly magazines, or gekkansi; many Senrian newspaper companies also publish weekly or monthly newsmagazines. The most prominent foreign-language magazine published in Senria is La Senrie, which is published in both Gaullican and Estmerish and features a mixture of journalism, criticism, commentary, and fiction.

Senria's public broadcaster is the Senrian Broadcasting Corporation, more commonly referred to as SHK. SHK was founded in 1925 and currently operates three terrestrial television channels (SHK TV 1, SHK TV 2, and SHK Educational TV), two AM radio stations (SHK Radio 1 and SHK Radio 2), and one FM radio station (SHK Radio 3), as well as the SHK World Service for international audiences. Major private radio networks in Senria include the Senria Radio Network, Daisenryuu Broadcasting System, Radio Senkei, Senrian FM Radio System, and Keisi Interwave FM; major commercial television networks include the Senrian Television Broadcasting System, Senzou Network System, Zensenryuu TV, and TV Keisi Network. The Telegraph Agency of Senria is the country's primary wire service.

While the Senrian government ended the country's press censorship during the premiership of Kiyosi Haruna, resulting in a large increase in the number of news outlets operating in Senria, international watchdogs and non-profit organizations have alleged that Senrian press freedom suffers from close ties between the national government and many major media corporations; these bonds allow the government to influence the tone of the coverage provided by the corporations in question. As many important Senrian newspapers, magazines, television networks, and radio broadcasters are affiliated with each other or owned by the same parent companies, this allows the Senrian government to control how news is reported without having to implement any formal restrictions on the press. Senrian dissidents sometimes derisively refer to Senria's mass media (masukomi) as "mass garbage" (masugomi) as a result.

Use of social media is also widespread in Senria. The instant messaging application MelonTalk is widely utilized domestically; internationally, however, Senria's most successful social media services are the microblogging website Chirper, which operates in Senria under the name Berinetto, and the video-sharing and social networking application Pinpin, itself derived from the video-sharing platform Pinpin Douga. In addition, some major foreign social media services have also made footholds in the Senrian market.

Senria possesses one of the world's most advanced telecommunications networks, with advanced broadcasting, telephone, and internet infrastructure broadly available nationwide. As a result of its leading role in technological research and the manufacturing of consumer electronics, services such as mobile broadband were widely available in Senria earlier than most other countries. Cell phones are ubiquitous in Senria; 67% of the Senrian population owned a smartphone as of 2017, and the Senrian Department of Communications reported in 2013 that the number of mobile phones in Senria was larger than the country's total population. Penetration of Internet service in Senria was measured at 92% of households and 99% of businesses as of 2019.

Under Senrian law, the government is required to own one-third of the shares in the Senrian Telegraph & Telephone Corporation and Senria Post Holdings Company, both of which were originally statutory companies turned into "private companies in public ownership" in the 1980s, in order to guarantee steady provision of their services to the general public.

Transportation

As of 2017, Senria had approximately 1,883,250 kilometers (1,170,200 miles) of roads, composed of roughly 1,584,100 kilometers (984,300 miles) of municipal roads, 201,800 kilometers (125,400 miles) of prefectural roads, 84,850 kilometers (52,700 miles) of national highways, and 12,500 kilometers (7,750 miles) of national toll expressways. Just over 90% of Senria's roadways are paved as of 2020. Much of the country's modern road network was constructed during the 1950s and 1960s, when the Senrian government adopted a series of plans aimed at expanding and paving the country's road network, or during the 1980s, when both road passenger and freight transport expanded dramatically. Municipal and prefectural roads are managed by local authorities; the country's highway system is managed by the national government, while the country's expressways are managed by the Zensenryuu Expressway Corporation, a state-owned enterprise originally founded as a public corporation in the 1950s before being privatized in the 1980s. The expressway networks of the islands of Kousuu, Kisima, Kanasima, Tousuu, and Yuusuu are connected by bridges; Gyousuu has a separate network, and Rousima, Narazima, and Kurosima have one expressway each. The Senrian government maintains a series of designated rest areas known as roadside stations alongside highways and prefectural roads, in order to provide travelers with a place to rest and to promote local tourism.

Though the relative share of railways in total passenger kilometers has fallen since the 1980s, rail remains a crucial means of passenger transport in Senria, particularly for mass transit, commuting, and high-speed travel. It is not nearly as important for freight, however; in 2017, only 6.2% of Senrian freight was transported by rail. The country has 42,132 kilometers (26,179 miles) of railway as of 2021, the large majority of which is narrow gauge, though a noteworthy proportion - particularly in newer sections of the country's rail network - is standard gauge. The Senrian railway network connects all four main islands of the Senrian archipelago through a series of bridges and tunnels. The country's primary rail operator is the Senria Railways Company (or SR), a state-owned company which operates almost all intercity rail services, though several private rail companies also exist and compete with SR on either the local or national level. Senria was a pioneer of high-speed rail, with the first of the country's famous sinkansen lines opening in 1964; these lines now run along roughly 3,700 kilometers (2,300 miles) of track and can run trains at up to 320 km/h (200 mph).

Senria also has several subway networks that operate in addition to its main rail lines. The largest of these is the Keisi Metro, which is among the largest systems in the world by annual ridership. Other Senrian cities with subway systems include Ubeyama, Isikawa, Tosei, Nisiyama, Kasaoka, Ueda, Koriyama, Hisakawa, Ukyou, and Sakata. Additionally, several Senrian cities operate commuter rail, automated guideway transit, or tramway systems. Most Senrian cities operate municipal bus networks as part of their public transit systems; intercity bus services are offered by the SR Bus Company, a subsidiary of Senria Railways, and by several private operators.

Senria has long been a seafaring country on account of its status as an island nation, and waterborne transport remains important in Senria. The country had 1,011 designated ports as of 2014; of these, twenty-four were designated as "major international ports" by the Senrian government, with another 127 designated as "important ports". The Senrian merchant marine has 996 ships of over 1,000 gross tonnage on its register, totalling 38,361,000 tons deadweight; however, only 18% of Senrian-owned capacity was registered in Senria as of 2008. An extensive network of ferries connect the various islands of the Senrian archipelago to each other; while the overall importance of ferry services has declined with the expansion of Senria's road and rail systems, they nonetheless remain important, particularly for transit to and from smaller islands. Additionally, the country has 1,973 kilometers (1,225 miles) of navigable waterways, though their use tends to be restricted to small craft.