Zhoushi language: Difference between revisions

m (Moved the history) |

m (→History) |

||

| Line 151: | Line 151: | ||

After the rebellions were suppressed, the authors writing in both Old and Slavic Zhengian were mostly enraged by the new censorship rules regarding the language use, as many archaic Old Zhengian words were no longer recognizable by the new generations and Old Zhengian effectively shrunk in vocabulary to the most basic terms used by the rich. As a result, many of those authors fled for [[Bogmia]], where they started writing literature instead. Although writing in Slavic Zhengian, many words from the hybrid, as well as limited vocabulary from Old Zhengian found their way through those texts into the Bogmian language. | After the rebellions were suppressed, the authors writing in both Old and Slavic Zhengian were mostly enraged by the new censorship rules regarding the language use, as many archaic Old Zhengian words were no longer recognizable by the new generations and Old Zhengian effectively shrunk in vocabulary to the most basic terms used by the rich. As a result, many of those authors fled for [[Bogmia]], where they started writing literature instead. Although writing in Slavic Zhengian, many words from the hybrid, as well as limited vocabulary from Old Zhengian found their way through those texts into the Bogmian language. | ||

After the failed experiment, Old Zhengian language went extinct even in the [[Zhengia|Zhengian]] nobility, and in 1698, Slavic Zhengian was declared an official language of the state, although its literaray form wasn't developed until 1728. | |||

===The Empire=== | ===The Empire=== | ||

Shortly after the creation of the [[Empire of Three Kings]], populations of the three kingdoms, but especially in border areas of [[Bogmia]] and [[Zhengia]] began to intermix. Due to somewhat strict rules on religion, many [[Silvadum City|Catholic]] Bogmians fled [[Bogmia]], which declared [[Kaȝin Christianity]] as its official religion, for [[Qazhshava]], where they created a linguistic enclave of Bogmian, which didn't integrate into the future Zhoushi language and conservated into the [[Pustogorian Bogmian language]], which is the only surivivng dialect of the Bogmian language outside of the hybrid Zhoushi. | |||

With the [[Bogmian Mountain Conflicts#Bogmian-Haldenian War|First]] and [[Bogmian Mountain Conflicts#War for the sea|Second]] Western Imperial Wars, waves of Bogmian settlers entered ethnically Haldenian territory. [[Haldenia]], until then, spoke a seperate Slavic languages, most notably Haldeno-Louzen languages, from which only [[Louzen language|Louzen]] survived to the present day, and Rohynrish branches, which created the backbone to the western Zhoushi dialects. | |||

===Zhoushi Cooperation=== | ===Zhoushi Cooperation=== | ||

TBA | TBA | ||

| Line 211: | Line 215: | ||

|--> | |--> | ||

|} | |} | ||

=Orthography and phonology= | =Orthography and phonology= | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

Revision as of 12:15, 13 June 2021

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

| Zhoushi | |

|---|---|

| Neo-Bogmian, Bogmo-Zhengian | |

| Ʒөшinчina - Ʒөшinƌky jєzyk | |

| |

| Pronunciation | /ʒu͡oʃɪnt͡ʃina/ |

| Native to | |

| Region | Slavic Belt in Thuadia |

| Ethnicity | Zhoushi Slavs |

Native speakers | L1: 110,985,000 L2: 12,532,000 FL: 7,230,000 |

Thuado-Thrismaran

| |

Standard forms | Great Corpus of the New Zhoushi language

|

| Dialects | |

| Zhoushi Latin Alphabet | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ZS |

| ISO 639-2 | ZSG |

| ISO 639-3 | ZSG |

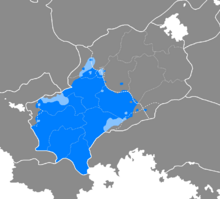

Distribution of the language

Absolute majority >30% of native speakers | |

The Zhoushi language is a Slavic language out of Kento-Polyash language group, which is a official language of Zhousheng and a official federal language in Mustelaria along with Belgorian and Neo-Mustelarian.

History

The Zhoushi language developed out of a synthesis two seperate languages, Bogmian, spoken in the historical areas of Bogmia, and Slavic Zhengian, spoken in the historical Zhengia. The Bogmian language was a child language to the Proto-Slavic language, while Slavic Zhengian was a macaronic language developed out of Old Zhengian, which was a language related to Preimeai, Zaprei and Phnom languages with extremely strong influence of the previously mentioned Bogmian.

Protohistory

Shortly after the Slavic migration and establishment of the Slavic belt in southern Thuadia, the languages began to differentiate. Slavs in the Mustelarian plain slowly formed a compact Proto-Polyash language, which in at around 5th century split into multiple dialects, which later merged and diversified, forming many languages currently present in the area (Zhoushi, Belgorian, Karaalani, Ulevan and Slovanic, as well as now extinct High Mustelarian).

Specifically, at the end of the 8th century, Ablative case got resurrected under yet unknown conditions in Bogmian. This change is often regarded as the beginning of the history of the Bogmian language proper.

Bogmian Empire

At around 800 AD, the first compact version of a language that later came into history as "Bogmian" was created in present day Plavlino and surrounding area. At the same time, the first ever compact country was formed in the region, the Bogmian Empire. The Empire came to occupy Zhengia and making it a Bogmian vassal for almost 300 years. At that time, Bogmian language absorbed multiple dialects, mostly in the central and northern areas.

At that time, the Old Zhengian language, not being Thuado-Thrismaran, but Prei-Phnom, was first introduced to the Slavic grammatical base, being subjected to foreign occupation and partial colonisation. At that time, Old Zhengian adapted grammatical numbers, as well as partial creation of grammatical cases (Protoversions of Zhengian subjective and objective cases).

Over the span of 300 years, in which the Bogmian Empire existed, Zhengian population, especially the northern parts and rural areas, was filled with Bogmian settlers. At the moment of collapse of the empire in 1103 AD, many areas in Zhengia have been already intermixed Old Zhengian-Bogmian.

The Dark Ages

After the Empire collapsed, areas of historic Bogmia and Zhengia shatterred into many protostates and small nations, which quickly began attacking each other. This era, colloquially named "The Dark Ages", was effectively a blow to the Old Zhengian language, which quickly began to deteriorate. Kaȝin Christianity, which was formed at around that time in Bogmia, caused many Zhengian noblemen to strictly oppose and persecute the local inteligence, fearing the spread of Kaȝinism south to the detriment of Kammism, to which their power was tied. Although this persecution was effective in securing their position, the language quality of Old Zhengian took a heavy blow.

With the more high-positioned Old Zhengian speakers, the macaronic Bogmio-Zhengian managed to take a deep root in Zhengia, being de facto the lingua franca of Zhengia by 1530. This new mostly Slavic-root language with heavy Old Zhengian influence is named "Slavic Zhengian"

Zhengian Experiment

– Korim the Terrible (Duke of Zhengia)

With the downfall of Old Zhengian in lower classess and the creation of Slavic Zhengian, the nobility grew scared of a possible alienation of lower nobelty and uprising that could cost them not only their positions, but also their lives. After the unification into a larger Duchy of Zhengia, the ruler Korim the Terrible (at the time known as Korim the Speaker) set a series of decrees hoping to get a resurgence of Old Zhengian to the lower nobility and cities. The Korim dynasty, starting with the "National Protection Decree" from 1591 started stepping up against the new cultural monolith that excluded themselves.

The moment this action was undertaken, many local lords, barons and lower dukes rose in open rebellion against the central authority. Although numerous, those uprising were put down, which only resulted in further decrease of the Old Zhengian power, as many of those noblemen were Old Zhengian natives and rose up because they assumed that the prescribtions against Slavic Zhengian are only a casus belli so the central authority can establish itself better to the detriment of the lower houses.

After the rebellions were suppressed, the authors writing in both Old and Slavic Zhengian were mostly enraged by the new censorship rules regarding the language use, as many archaic Old Zhengian words were no longer recognizable by the new generations and Old Zhengian effectively shrunk in vocabulary to the most basic terms used by the rich. As a result, many of those authors fled for Bogmia, where they started writing literature instead. Although writing in Slavic Zhengian, many words from the hybrid, as well as limited vocabulary from Old Zhengian found their way through those texts into the Bogmian language.

After the failed experiment, Old Zhengian language went extinct even in the Zhengian nobility, and in 1698, Slavic Zhengian was declared an official language of the state, although its literaray form wasn't developed until 1728.

The Empire

Shortly after the creation of the Empire of Three Kings, populations of the three kingdoms, but especially in border areas of Bogmia and Zhengia began to intermix. Due to somewhat strict rules on religion, many Catholic Bogmians fled Bogmia, which declared Kaȝin Christianity as its official religion, for Qazhshava, where they created a linguistic enclave of Bogmian, which didn't integrate into the future Zhoushi language and conservated into the Pustogorian Bogmian language, which is the only surivivng dialect of the Bogmian language outside of the hybrid Zhoushi.

With the First and Second Western Imperial Wars, waves of Bogmian settlers entered ethnically Haldenian territory. Haldenia, until then, spoke a seperate Slavic languages, most notably Haldeno-Louzen languages, from which only Louzen survived to the present day, and Rohynrish branches, which created the backbone to the western Zhoushi dialects.

Zhoushi Cooperation

TBA

Unified nation

TBA

Comparison with the two former languages

| Aspect | Bogmian | Zhengian | Zhoushi | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genders | YES | NO | YES | ||

| Clusivity | NO | YES | YES | ||

| Vowel length | YES | NO | NO | ||

| Syllabicity | YES | NO | YES | ||

| Reflexive | YES | NO | YES | ||

| Cases | YES | ??? | YES | ||

| Dozenal | NO | YES | ??? | ||

| Indifference | NO | YES | YES |

Orthography and phonology

Introduction

The language has a slavic root and grammar, however, unlike other slavic languages, has 8 grammatical cases (other have 7 or 6). Also, there are about 700 Zhengian words in present day Zhoushi language, they are inflected using Bogmian grammar. Old Zhengian, having been descendant out of Prei-Phnom languages, was slowly assimilated into Slavic grammar, having transformed into Slavic Zhengian. Because of the Zhengian accents profilerating, Zhoushi language has 40 unique phonemes, 2 of which are exclusive to Zhoushi language (those are /r̝̊/ (Voiceless alveolar fricative trill)[5] and /ȴ̩/ (Syllabic voiced alveolo-palatal lateral approximant)).

Alphabet

After the reform of 1912, when Bogmian language officially abandoned Protopolyash script in favor of the new Latin script, hoping to solve the problematic grammar, as multiple phonemes shared one symbol (such as "i" and "j" were both noted as "ⲓ") Three official versions of the new script had been made:

| A a | B b | C c | Ч ч | D d | Đ đ | Ƌ ƌ | E e | Є є | F f |

| G g | Џ џ | H h | Ȝ ȝ | I i | J j | K k | L l | Λ λ | M m |

| N n | Ƞ ƞ | O o | Ө ө | P p | Q q | R r | Ꝛ ꝛ | S s | Ш ш |

| T t | Ꞇ ꞇ | Þ þ | U u | V v | Ƿ ƿ | X x | Y y | Z z | Ʒ ʒ |

- Grapheme version: This version was later adopted as the official alphabet of the new Zhoushi language in 1984, uses special symbols for each phoneme

- Diacritic version: This version uses basic latin alphabet and solves the phonemes by adding diacritic symbols. Although still being recognized as a acceptable version of the language, it is barely used.

- Digraph version: This version uses digraphs to sign specifical phonemes. It was dropped in early 1950's, as it didn't solve the main reason why Bogmians abandoned the Protopolyash script in the first place.

Zhoushi, although not officially using it, sometimes used lenghtened marks for vowels and syllabic consonants. Those symbols were used in some historical transcripts, but were eventually faded in pre-1950's unification proposals and didn't make it into the official grammar of 1984.

| Order | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Majuscule | A | B | C | Ч | D | Đ | Ƌ | E | Є | F | G | Џ | H | Ȝ | I | J | K | L | Λ | M |

| Minuscule | a | b | c | ч | d | đ | ƌ | e | є | f | g | џ | h | ȝ | i | j | k | l | λ | m |

| IPA Sound | a | b | t͡s | t͡ʃ | d~ɖ | ɟ | d͡z | ɛ | e | f | ɡ | d͡ʒ | h~ɦ | x | i | j | k | l | ȴ~ʎ | m |

| Order | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 |

| Majuscule | N | Ƞ | O | Ө | P | Q | R | Ꝛ | S | Ш | T | Ꞇ | Þ | U | V | Ƿ | X | Y | Z | Ʒ |

| Minuscule | n | ƞ | o | ө | p | q | r | ꝛ | s | ш | t | ꞇ | þ | u | v | ƿ | x | y | z | ʒ |

| IPA Sound | n | ɲ | o | u͡o | p | k͡v~q | r | r̝ | s | ʃ | t~ʈ | c | θ~ð | u | v | w | k͡s | y | z | ʒ |

Phonology

| Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | Laryngeal | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Linguolabial | Dental | Alveolar | Postal-veolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||||||||||||

| Nasal | m̥ | m | n | ɳ | ɲ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Plosive | p | b | t | d | ʈ | ɖ | c | ɟ | k | g | q | |||||||||||||

| Sibilant affricate | ʦ | ʣ | ʧ | ʤ | tʂ ~ ʈʂ | dʐ ~ ɖʐ | ʨ | ʥ | ||||||||||||||||

| Non-sibilant affricate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sibilant fricative | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | ʂ | ʐ | ɕ | ʑ | ||||||||||||||||

| Non-sibilant fricative | f | v | θ | ð | ʝ | x | ɣ | χ | h | ɦ | ||||||||||||||

| Approximant | ʋ | j | w | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Tap/Flap | ɾ̥ | ɾ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trill | r̥ ~ r̝̊ | r ~ r̝ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Latelar affricate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Latelar fricative | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Latelar approximant | l | ȴ | ʟ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Latelar tap/flap | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tongue position | Front | Near-front | Central | Near-back | Back | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | y | ɨ | u | ||||||

| Near-close | ɪ | |||||||||

| Close-mid | e | o | ||||||||

| Mid | ə | |||||||||

| Open-mid | ɛ | ʌ | ɔ | |||||||

| Near-open | æ | ɐ | ||||||||

| Open | a | ɑ | ɒ | |||||||

| Diphthong | a͡u ~ ɛ͡u ~ e͡u ~ o͡u ~ ɔ͡u ~ u͡o ~ u͡ɔ ~ a͡e ~ a͡i | |||||||||

| Long vowels | aː ~ ɛː ~ eː ~ iː ~ ɪː ~ oː ~ ɔː ~ uː ~ ɨː | |||||||||

Bold are the common sounds, while regular sounds may happen in dialects and/or in a world for easier pronunciation

Grammar

The Zhoushi language knows two grammatical numbers, singular and plural (with some remnants of the Dual number) and all 8 Proto-Thuado-Thrismaran grammatical cases:

- Nominative - Named "Miƞik"

- Genitive - Named "Rodƞik"

- Dative - Named "Darƞik"

- Accusative - Named "Viƞik"

- Locative - Named "Mistƞik"

- Instrumentative - Named "Tvorƞik"

- Ablative - Named "Mєrƞik"

- Vocative - Named "Volaƞik"

Nouns

The Zhoushi language recognizes 4 grammatical genders and then a set of words with no gender:

- Masculine

- Masculine animate - 4 inflection patterns

- Masculine inanimate - 4 inflection patterns

- Feminine - 4 inflection patterns

- Neuter - 4 inflection patterns

- Indifferent (that is not a gender, but a lack of gender) - 2 inflection patterns

Adjectives

There are 4 inflection patterns for adjectives, being a combination of hard/soft and descriptivity/possessivity:

- Descriptive soft

- Descriptive hard

- Possessive soft

- Possessive hard

In the declinations of adjectives, Vocative has merged with Nominative.

Pronouns

The Zhoushi language has following pronouns:

- Singular

- Ja (GEN Miƞe) - I/Me

- Ty (GEN Tebe) - You

- Өn (GEN Ƞej/Jego/Jeho) - He/Him

- Өna (GEN Ƞi/Jej) - She/Her

- Өno (GEN Өnogo/Өnoho) - It/Its

- Өnu (GEN Ƞij/Joj) - They/Them

- ACC Se (GEN Sebe) - -self

- Plural

- Ny (GEN Nas) - Inclusive we

- Vy (GEN Vas) - You

- Oni (GEN Ƞiȝ/Jiȝ) - They/Them (masculine)

- Ony (GEN Ƞeȝ/Jeȝ) - They/Them (feminine)

- Ona (GEN Ƞєȝ/Oƞєȝ) - They/Them (neuter + indifferent)

- My (GEN Mas) - Exclusive we

- ACC Sє (GEN Sєbe) - -selfves

Numbers

Until 1970's, Zhousheng used dozenal numerical system, substituting 10 a 11 with ᚴ and ⵒ. The last symbol used was so called "Cyclic symbol", which was used for twelve-step cycles and sets of twelve parts, which was written as ᘐ.

This system can be still seen for example on the Zhoushi clock faces, which are still using the old system, writing it as 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-ᚴ-ⵒ-ᘐ.

Verbs

TBA

Language examples

Lord's prayer

Following text shows Lord's prayer compared to Belgorian and Slovanic languages

| Common language | Zhoushi (Grapheme) | Zhoushi (Diacritic) | Belgorian (Protopolyash) | Belgorian (Diacritic) | Slovanic langauge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our Father in heaven, | Oþчe naш, kitory jesꞇєш na ƞieby, | Ot́če naš, kitory jesťěš na ňieby, | ⲟⲧⲕⲓ ⲛⲁϣⲓ, ⲧⲓϣ ⲓⲥⲉϣ ⲛⲁ ⲛⲓⲉⲃϣⲓⲭⲁⲭ, | Otki naši, tiš iseš na niebšichach, | Otče náš, ktorý si na nebesiach, |

| hallowed be your name. | mino Tiƿe buđ posviƌeno, | mino Tiwe buď posvid́eno, | ⲡⲟⲥⲫⲁⲧⲓⲓ ⲥⲁ ⲙⲉⲛⲟ ⲧⲯⲟⲓⲟ, | Posfatii sa meno Tvoio, | posväť sa meno Tvoje, |

| Your kingdom come. | Tiƿoje guo pꝛiȝađ, | Tiwoje guo přiȟaď, | ⲡⲣⲓⲓⲭⲟⲇⲓⲓ ⲕⲣⲁⲗⲫⲥⲧⲯⲟ ⲧⲯⲟⲓⲟ, | Priichodii kralfstvo Tvoio, | príď kráľovstvo Tvoje, |

| Your will be done, | biduч Tiƿuj janџ, | biduč Tiwuj janǧ, | ⲃⲓⲓ ⲯⲩⲟⲗⲁ ⲧⲯⲟⲓⲁ, | bii vuola Tvoia, | buď vôľa Tvoja, |

| on earth as it is in heaven. | jak v ƞeby, tak aj na zөmi. | jak v ňeby, tak aj na zǒmi. | ⲓⲁⲕ ⲯ ⲛⲓⲉⲃⲓ, ⲧⲁⲕ ⲁⲓ ⲛⲁ ⲍⲉⲙⲛⲓ. | iak v niebi, tak ai na zemni. | ako v nebi, tak i na zemi. |

| Give us this day our daily bread | Ȝilab maш tudejшij divaj mam dƞes | Ȟilab maš tudejšij divaj mam dňes | ⲭⲗⲓⲉⲃⲓⲕ ⲛⲁϣ ⲯⲍⲇⲉⲓϣⲁⲓ ⲇⲁⲓ ⲛⲁⲙ ⲇⲛⲓⲉⲥ | Chliebik naš daj nam dnies | Chlieb náš daj nám dnes |

| and forgive us our debts, | aj ƿypujuшꞇaj mam џriȝy maшije, | aj wypujušťaj mam ğriȟy mašije, | ⲓ ⲟⲇⲡⲩϣⲧⲓ ⲛⲁⲙ ⲛⲁϣⲓⲉ ⲯⲓⲛⲓⲉ, | i odpušti nam našie vinie, | a odpusť nám naše viny, |

| as we also have forgiven our debtors. | jak aj my ƿypujuшamy mašim huoqum. | jak aj my wypujušamy mašim huoqum. | ⲓⲁⲕ ⲓ ⲙⲓ ⲟⲇⲡⲩϣⲧⲓⲁⲙⲉ ⲛⲁϣⲓⲙ ⲯⲓⲛⲓⲕⲁⲙ. | iak i mi odpuštiame našim vinikam. | ako i my odpúšťame svojim vinníkom. |

| And do not bring us into temptation, | Aj ƞevydaj mas fu pakuшenji, | Aj ňevydaj mas fu pakušenji, | ⲓ ⲛⲓⲉⲍⲯⲓⲉⲇⲁⲓ ⲛⲁⲥ ⲯ ⲡⲟⲕⲩϣⲓⲉⲛⲓⲉ, | I nezvidai nas v pokušenie, | A neuveď nás do pokušenia, |

| but rescue us from the evil one. | le zibafuj mas ƿy Jingu. | le zibafuj mas wy Jingu. | ⲁⲗⲓⲉ ⲭⲣⲁⲛⲓⲓ ⲛⲁⲥ ⲟⲇ ⲍⲗⲟⲅⲟ. | ale chrani nas od Zlogo. | ale zbav nás Zlého. |

Interactive analysis of the prayer

Common:

Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name. Your kingdom come. Your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. And do not bring us to the time of trial, but rescue us from the evil one. Amen.

Zhoushi:

Oþчe maш, kitory jesꞇєш na ƞieby, mino Tiƿe buđ posviƌeno. Tiƿoje guo pꝛiȝađ. Biduч Tiƿuj janџ, jak v ƞieby, tak aj na zөmi. Ȝilab maш tudejшij divaj mam dƞes. Aj ƿypujuшꞇaj mam џriȝy maшije, jak aj my ƿypujuшamy mašim huoqum. Aj ƞevydaj mas fu pakuшenji,[6] le zibafuj mas ƿy Jingu. Amen.

IPA:

[oθ.t͡ʃɛ ˈmaːʃ | ˈki.to.rɨ ˈjɛ.scɛʃ na ˈɲie.bɨ | ˈmi.no ˈti.we ˈbuɟ ˈpo.svi.d͡ze.no ‖ ˈti.wo.jɛ guo ˈpr̝̊i.ɣaɟ ‖ ˈbi.dut͡ʃ ˈti.wuj ˈjand͡ʒ | ˈjak ˈfu ˈɲie.by | ˈtak ˈaj ˈna ˈzu͡o.mi ‖ ˈxi.lab ˈmaʃ ˈtu.dɛj.ʃij ˈdi.vaj ˈmaːm ˈdɲɛs ‖ ˈaj wɨ.pu.ju.ʃcaj ˈmaːm ˈd͡ʒiː.xɨ ˈma.ʃi.je | ˈjak ˈaj wɨ.pu.ju.ʃa.mɨ ˈmaʃ.im ˈhu.o.k͡vum. ‖ ˈaj ˈɲɛ.vɨ.daj ˈmaːs ˈfu ˈpa.ku.ʃen.ji | ˈlɛ ˈzi.ba.fuj ˈmaːs ˈwɨ ˈjin.gu ‖ ˈaː.mɛn]

World Peace Manifesto

World Peace Manifesto is the founding agreement, that formed the Anterian World Assembly. The document, although being written in Common was originally written by Mustelarian prime minister Jeliþo Pogөf, a native Zhoushi, who later translated this matterial into Zhoushi. Interactive translation includes the first paragraph of the text:

Interactive analysis of the manifesto

Common:

We, the nations of Anteria, hereby stand together, working together, united and willing to cooperate to reach global peace. We have seen enough deaths, enough suffering, enough pain and enough ruined lives. We came together with a hope and a ideal, that there are things that should be done, there are ways better than war, there is a better way to work with the world.

Zhoushi:

Ny, narody Anterje, ƿustavame pospolu, pracujiƌ pospolu, odnetƞi aj ȝoчuƌ spөlupracovaч k dosaʒenje ʒөmskeho santifu. Ny viџali pꝛiliш smrꞇiȝ, pꝛiliш utrpeƞi, pꝛiliш bөlu aj pꝛiliш zƞiчoniȝ чiƿtu. Ny sє sȝromaʒđili s virө aj idealem, ʒto jsu vjeƌi, kitore by miaλy byч đelane, jsu moʒnosꞇi lepшє neʒ vojna, je moʒnosꞇ pracovaч se шtaty zөme.

IPA:

[nɨ ˈna.ro.dɨ ˈan.te.rʲɛ ˈpu.sta.va.mey ˈpospolu | ˈpra.t͡su.jid͡z ˈpo.sp.olu | ˈod.nɛ.tɲi ˈaj ˈxo.t͡ʃud͡z ˈspu͡o.lu.pra.t͡so.vat͡ʃ k ˈdo.sa.ʒɛn.jɛ ˈʒu͡om.ske.ho ˈsan.ti.fu ‖ ˈnɨ ˈvi.d͡ʒa.li pr̝̊iː.liʃ. ˈsmr.cix | ˈpr̝̊iː.liʃ ˈu.tr.pɛ.ɲiː | ˈpr̝̊iː.liʃ ˈbu͡o.lu aj ˈpr̝̊iː.liʃ ˈzɲi.t͡ʃo.nix ˈt͡ʃiw.tuː ‖ nɨ se ˈsɣro.maʒ.ɟi.li s ˈvi.ru͡o aj ˈi.dɛ.aː.lem | ˈʒto ˈjsu ˈvje.d͡zi | ˈki.to.rɛ ˈby ˈmia.ȴɨ ˈbɨt͡ʃ ˈɟe.la.nɛ | ˈjsu ˈmo.ʒno.sci ˈlɛp.ʃe ˈnɛʒ ˈvoj.na | ˈjɛ ˈmoʒ.nosc ˈpra.t͡so.vat͡ʃ se ˈʃta.tɨ zu͡o.me]

First words from the Moon

First country to land people on the Moon was San Calia, which successfully got a lunar lander with two people in Mare Unitaris on July 20th, 1967. Calonaut David Russel was the first to touch the surface of the Moon, saying the quote seconds after climbing down the ladder. Interactive translation of the quote:

Interactive analysis of the first words

Common:

We come in the name of San Calia, for Anteria, and for all mankind.

Zhoushi:

Pꝛiȝazimy ve minu Svekalije, pro Anterji, aj pro cөle λuƌitvo.

IPA:

[pr̝̊i.xa.zi.mɨ ˈve ˈmi.nu ˈsve.ka.li.je ˈpro ˈan.te.rʲi ˈaj ˈpro ˈt͡su͡o.le ˈȴu.d͡zi.tstvo]

The Universal Phrase

Common:

My hovercraft is full of eels.

Zhoushi:

Moje vzaшeloџ je plna voguꝛ.

IPA:

[ˈmo.jɛ ˈvza.ʃe.lod͡ʒ ˈje ˈpl̩.naː ˈvo.gur̝̊]

See also

- ↑ Bogmo-Zhengian dialect is the most "literal", as its base was taken for the design of the new language in early 80's and was later codified in 1984

- ↑ Official languages of the Sekidean Union are official languages of countries that are members. Therefore, Zhoushi is considered an official language, although on the international basis, Common is used the most.

- ↑ The word "bastard" is used in this case in its original meaning, that is as a illegitimate childs, in this case a reference to their lack of legitimacy to claim the metaphorical power in city guilds and lower nobility

- ↑ At the time, there were two Bogmian Duchies and three smaller constituent nations with the name "Bogmian" in some form in their name, so this reference is metaphorical, discussing the hypothetical common enemy to be Bogmians in general rather than some power

- ↑ Note: this phoneme is present in other two Kento-Polyash languages: Velnotian and Ulevan

- ↑ Other version is "(...) Aj ƞedaj abyȝom nebyli vydaƞi fu pakuшenji, (...)" This version is favored by Kaȝin Christians, while the Catholic Christians prefer the version listed above.

- Language articles with speaker number undated

- Mustelaria

- Anteria

- Languages with ISO 639-2 code

- Languages with ISO 639-1 code

- Language articles without reference field

- Language articles missing Glottolog code

- Language articles with unsupported infobox fields

- Non-canon articles

- Languages in Anteria

- Kento-Polyash languages