People’s War

| People's War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

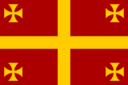

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

80,000 infatry 25,000 Loyalist militiamen 13,000 cavalry |

15,000 Royal Marines 120,000 militiamen 5,000 cavalry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Total dead 55,000 Total wounded: 87,000 |

Total dead: 73,000 Total wounded: 95,000 | ||||||

| |||||||

The People's War (Salvian: Pallo dox Taulus) was a 2-year civil war between democratic and monarchical forces in the Marenesian Divine Imperium of Salvia. Beginning on November 29th, 1707, it began after the firing on a federal fort off the coast of St. Paul’s by democratic forces, responding to many grievances committed by the monarch of the time, Peter III. It ended in a democratic victory, with the del Monte dynasty being overthrown and the institution of a new Constitution, forming the modern government type of the Divine Republic.

Background

In 1695, the Divine Imperium of Salvia was a colonial empire that stretched from the New Wurld to Marenesia Minor and enjoyed a vast trading network. Seeking to expand the empire, the monarch, Peter III wanted a more forward shipping outpost to the New Wurld and so conquered Catholic Aslonia. While the military campaign was initially successful, native Marenai began to fiercely resist Salvian occupation, leading Peter III to station more troops on the island in order to combat the unrest, however simultaneous conflicts with northern neighbors and Anglish settlers on Aramoana, insurrections in northwestern Alvernia, overseas colonial wars meant the king was forced to increase the size of the military, which he did by both impressment and by encouraging citizens to join through increased promises of payment for their service. To pay for the larger military, Peter III increased taxes on land and trade, angering much of the upper and middle class as well as the Salvian Catholic Church.

Trinity Massacre and Outbreak of War

Leadup to the Trinity Massacre

By the late 1600s, the costly wars and expeditions funded by the monarchs of Salvia had become incredibly unpopular among most of the populace. To fund these conflicts, the monarch had levied heavy taxes on land and trade which angered much of the upper and middle class. Besides this, further centralization of power meant the reduction of power for the nobility, angering them further. In an attempt to regain support, Peter III introduced several laws that granted nobles greater control over wages and living conditions for their laborers, cut back taxes on the wealthy, and reintroduced new taxes on the urban working and middle class. While appeasing the nobility somewhat, Peter further angered the middle and lower classes. The Salvian Catholic Church, under the leadership of Pope Pius IV, at first supported Peter III but was soon turned against him as he applied taxes on Church property.

The Concilio Populi, controlled by much of the middle class, and the Concilio Clerici began drafting peace deals for the rebels in Catholic Aslonia in early 1707 to end the war. After discovering this, Peter III illegally evoked the powers of the Concilios and dissolved them with military force on 3 March 1707. Protests immediately erupted across northern Salvia and St. Paul's island as the war in Catholic Aslonia continued. Tensions were further fueled when leaders of protests on the Sicani Islands were executed for treason. In retaliation, conspirators planned for the assassination of the Minister of War, but were caught and executed.

Certain provinces and governors opposed to the king began forming an alliance and formed their own Concilio Populi, led by Governor of the Sicani Islands Jacob Bern. Bern soon after declared a new republic that was to replace the king. Peter III, now dealing with a rapidly escalating crisis, attempted to compromise with the seceding states by reducing taxes and providing benefits for mostly the ruling class. The provinces refused, and more began to join the new republic - by the Trinity Massacre, 14 out of the 23 provinces in the empire had seceded compared to just 8 a month after the dissolution of the Concilios.

Trinity Massacre

Protests began to grow as the supposed grievances continued to worsen. Taxes were raised and enforced more strictly as Peter's War endured, and the official Concilios were still forced from convening. On 15 November, eight months after the crisis had first begun, protesters in the northeastern city of Trinity began to gather in the city's port in large numbers, harassing armed soldiers of the Crown. The stand-off that ensued would lead to the commanding officer giving the order to the soldiers to shoot, causing 17 deaths and leaving around 50 injured.

The consequences of the massacre were felt immediately. Revolutionary leaders, including humanist thinker Leo Angelo and governor Jacob Bern, used the massacre as a rallying cry for secession and revolution. Many moderates who sought a peaceful solution to the crisis switched sides and joined the revolutionaries as 13 more provinces joined the new republic. Emboldened by growing support, provinces also began to seize federal forts, arsenals, and outposts, gathering arms as they also instituted conscription. Peter III, seeking a peaceful resolution, offered pardons for the governors in return for the dissolvement of the United Provinces; the governors refused.