Pecario: Difference between revisions

Mr.Trumpet (talk | contribs) m (→Seaports) |

Mr.Trumpet (talk | contribs) |

||

| (21 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

<!-- CULTURE --> | <!-- CULTURE --> | ||

| official_languages = [[Iverican]], [[Stillian]] | | official_languages = [[Iverican]], [[Stillian]] | ||

| national_languages = Iverican, Stillian Iverican, Stillian, Quepec, | | national_languages = Iverican, Stillian Iverican, Stillian, Quepec, Andyo, other indigenous languages | ||

| regional_languages = | | regional_languages = | ||

| languages_type = <!--Use to specify a further type of language, if not official, national or regional--> | | languages_type = <!--Use to specify a further type of language, if not official, national or regional--> | ||

| Line 486: | Line 486: | ||

At the international level, Pecario aims to strengthen its relations with other countries of the world, especially those with similar interests in sustainable development, environmental protection and the promotion of human rights. Due to its history and natural wealth, Pecario also attracts the attention of foreign investors and business partners. Pecario's government seeks to encourage foreign investment while protecting national interests and ensuring that foreign companies operate in accordance with the country's laws and regulations. | At the international level, Pecario aims to strengthen its relations with other countries of the world, especially those with similar interests in sustainable development, environmental protection and the promotion of human rights. Due to its history and natural wealth, Pecario also attracts the attention of foreign investors and business partners. Pecario's government seeks to encourage foreign investment while protecting national interests and ensuring that foreign companies operate in accordance with the country's laws and regulations. | ||

Pecario is a full member of the [[Entente of Oriental States]] since 2023 (the country had previously been an observer since December 2017). | |||

Despite its efforts to promote positive relations with other countries, Pecario also faces challenges internationally, including issues related to security, drug trafficking and corruption. These issues influence relations with certain countries, but the Pecarian government is trying to resolve them through dialogue and cooperation. | Despite its efforts to promote positive relations with other countries, Pecario also faces challenges internationally, including issues related to security, drug trafficking and corruption. These issues influence relations with certain countries, but the Pecarian government is trying to resolve them through dialogue and cooperation. | ||

| Line 538: | Line 540: | ||

| [[File:Flag of Cusco (1540–1978).svg|150px]] || '''Santa Borbones''' || [[Santa Borbones]] || [[Antonio Jose Montemayor]] || 1,500,000 | | [[File:Flag of Cusco (1540–1978).svg|150px]] || '''Santa Borbones''' || [[Santa Borbones]] || [[Antonio Jose Montemayor]] || 1,500,000 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Flag of Port Louis, Mauritius.svg|150px]] || '''Costa | | [[File:Flag of Port Louis, Mauritius.svg|150px]] || '''Costa Esmeralda''' || [[San Luis (Pecario)|San Luis]] || [[Clément Desmoulins]] || 4,000,000 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Flag of Asunción.svg|150px]] || '''Fortaleza''' || [[Iochia]] || [[Biel Montilla]] || 2,000,000 | | [[File:Flag of Asunción.svg|150px]] || '''Fortaleza''' || [[Iochia]] || [[Biel Montilla]] || 2,000,000 | ||

| Line 609: | Line 611: | ||

Pecario does have domestic {{wp|fossil fuel}} reserves, primarily of {{wp|petroleum}} and {{wp|natural gas}}; exports of oil and natural gas combined represent about 12% of the country's mineral exports, and {{wp|fossil energy}} represents 23% of the country's electricity generation. However, Pecario's domestic refining capability cannot meet demand, and so the country has to import {{wp|fuel oil}}, {{wp|gasoline}}, and {{wp|diesel}}. The Pecarian government has also encouraged investment in the production of {{wp|Ethanol fuel|ethanol}} from {{wp|Maize|corn}} & {{wp|sugarcane}} and {{wp|biodiesel}} from {{wp|soybean oil|soybeans}}, which would allow the country to take advantage of its agricultural sector for energy production. | Pecario does have domestic {{wp|fossil fuel}} reserves, primarily of {{wp|petroleum}} and {{wp|natural gas}}; exports of oil and natural gas combined represent about 12% of the country's mineral exports, and {{wp|fossil energy}} represents 23% of the country's electricity generation. However, Pecario's domestic refining capability cannot meet demand, and so the country has to import {{wp|fuel oil}}, {{wp|gasoline}}, and {{wp|diesel}}. The Pecarian government has also encouraged investment in the production of {{wp|Ethanol fuel|ethanol}} from {{wp|Maize|corn}} & {{wp|sugarcane}} and {{wp|biodiesel}} from {{wp|soybean oil|soybeans}}, which would allow the country to take advantage of its agricultural sector for energy production. | ||

[[File: | [[File:Adventures-in-pecario-1.jpg|thumb|275px|Tourist guide to visit Pecario.]] | ||

===Tourism=== | ===Tourism=== | ||

| Line 617: | Line 619: | ||

Natural areas are a major attractor for tourists to Pecario as a result of the country's geographic diversity, allowing for a variety of {{wp|leisure}} and {{wp|Recreation|recreational}} activities. Beachgoing is extremely popular for domestic and foreign tourists alike, with the country boasting a variety of fantastic beaches along its Manamaman Bay coastline; the islands of the [[Alcazara|Alcazara archipelago]] and Isla Penã, Caravalla, in particular have been heavily promoted for international tourists by the Pecarian Ministry of Tourism in recent years. The Cordillera del Sol provide ample opportunities for {{wp|hiking}} and similar activities. {{wp|Ecotourism}} and environmental {{wp|International volunteering|voluntourism}} are important parts of the Pecarian tourism sector, especially in the Verde Rainforest and {{wp|pantanal}}, as a result of the country's immense biodiversity and many national parks. The country also provides many opportunities for {{wp|Adventure travel|adventure tourism}}. | Natural areas are a major attractor for tourists to Pecario as a result of the country's geographic diversity, allowing for a variety of {{wp|leisure}} and {{wp|Recreation|recreational}} activities. Beachgoing is extremely popular for domestic and foreign tourists alike, with the country boasting a variety of fantastic beaches along its Manamaman Bay coastline; the islands of the [[Alcazara|Alcazara archipelago]] and Isla Penã, Caravalla, in particular have been heavily promoted for international tourists by the Pecarian Ministry of Tourism in recent years. The Cordillera del Sol provide ample opportunities for {{wp|hiking}} and similar activities. {{wp|Ecotourism}} and environmental {{wp|International volunteering|voluntourism}} are important parts of the Pecarian tourism sector, especially in the Verde Rainforest and {{wp|pantanal}}, as a result of the country's immense biodiversity and many national parks. The country also provides many opportunities for {{wp|Adventure travel|adventure tourism}}. | ||

{{wp|Cultural tourism}} is also a major sector of the Pecarian tourism industry as a result of Pecario's remarkable historic and cultural patrimony. The indigenous civilizations of Pecario left a rich archaeological and cultural impact upon the nation, and many pre-colonial sites are now important tourist attractions. These include the archaeological sites at [[Cùnchalan]], [[Valcambila]], and [[ | {{wp|Cultural tourism}} is also a major sector of the Pecarian tourism industry as a result of Pecario's remarkable historic and cultural patrimony. The indigenous civilizations of Pecario left a rich archaeological and cultural impact upon the nation, and many pre-colonial sites are now important tourist attractions. These include the archaeological sites at [[Cùnchalan]], [[Valcambila]], and [[Kállanka]], as well as the famous {{wp|Nazca lines|Guanamo geoglyphs}} and the citadel of [[Fortaleza de la Costa]]. Tourists also come to see preserved Iberic colonial architecture, most of it in the famous {{wp|Andean Baroque|Cordilleran Baroque}} style, with the historic centers of [[Santa Borbones]], [[Valleluz]], and [[San Luis (Pecario)|San Luis]] all home to famous examples of preserved colonial buildings. Santa Borbones is also known for its many museums. {{wp|Culinary tourism|Gastrotourism}} is a noteworthy subset of cultural tourism within Pecario, with tourists attracted to the unique synthesis of indigenous, colonial, and immigrant traditions offered by Pecarian cuisine. | ||

== Transportation == | == Transportation == | ||

| Line 649: | Line 651: | ||

== Demographics == | == Demographics == | ||

According to the last two censuses carried out by the Pecarian National Statistics Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, INE), the population increased from 25,089,468 in 2003 to 29,059,856 in 2023. In the last fifty years the | According to the last two censuses carried out by the Pecarian National Statistics Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, INE), the population increased from 25,089,468 in 2003 to 29,059,856 in 2023. Traditionally a rural nation, Pecario has seen widespread urbanization in recent decades, and at least two-thirds of the country's population now lives in urban areas. In the last fifty years the Pecarian population has tripled, reaching a population growth rate of 2.25%. Some 67.55% of Pecarians live in urban areas, while the remaining 32.45% in rural areas. According to the 2012 census, 58% of the population is between 15 and 59 years old, 41% is less than 15 years old. Almost 65% of the population is younger than 25 years of age. The country has an overall literacy rate of 92%, with illiteracy rates higher among the poor, the elderly, and the inhabitants of rural areas. | ||

The Pecarian population is very ethnically diverse, having been shaped by multiple waves of immigration over successive centuries of habitation, with the country's modern population descended from various populations of indigenous Pecarians, Iberic colonists and settlers, [[Per-Aten|Atenic]] and various [[Europa|Europan]] and ethnicities that immigrated to the country in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As a result of this diversity, Pecario is commonly considered a {{wp|Multiculturalism|multicultural}} society. Pecario's census, conducted by the Instituto Pecariano de Estadística y Geografía (Pecarian Institute of Statistics and Geography), or IPEG, reports ethnic data. | |||

{{Pie chart | |||

| thumb = right | |||

| caption = <center>'''Ethnic demographics of Pecario'''</center> | |||

| other = | |||

| label1 =Albianos | |||

| value1 =10.0 | |||

| color1 =#9C0E0E | |||

| label2 =Mezcla | |||

| value2 =55.0 | |||

| color2 =#176E29 | |||

| label3 =Quepec | |||

| value3 =15.0 | |||

| color3= #08639C | |||

| label4 =Andyo | |||

| value4 =10.0 | |||

| color4= #E6BF0C | |||

| label5 =Other indigenous | |||

| value5 =7.0 | |||

| color5 =#800080 | |||

| label6 =Other/not stated | |||

| value6 =3.0 | |||

| color6 =LightBlue | |||

}} | |||

Roughly 10.0% of the Pecarian population identifies as ''Albianos'', or white Pecarians. The term "''{{wp|Criollo people|Embarrados}}''" emerged during the colonial period and originally referred to ethnic Iberic who had been born in Mesothalassa, in contrast to the ''{{wp|Peninsulares|Sotivales}}'', ethnic Ruttish born in [[Euclea]]. While most modern ''Albianos'' are descended from these original Iberic colonists, the term's use has been broadened in subsequent centuries to refer to all Pecarians of Europan origin, as a result, the term now also encompasses the descendants of 19th- and 20th century Europan immigrants to Pecario. These Europan immigrants came from a variety of countries, including [[Red Iberos]], [[Mantella]], [[San Gorgio]] and [[San Jorge]], and while most have at least partially assimilated into the broader ''Albianos'' population, many do retain unique features of their cultural heritage. | |||

''[[Mezcla]]'', or individuals of mixed ethnic origin, make up approximately 55% of the Pecarian population, making them the largest ethnic group in the country. While most associated with individuals of mixed Europan, indigenous Pecarians descent, the term "''{{wp|Mestizo|Mezcla}}''" can and regularly does refer to any person of multiracial or multiethnic descent. | |||

=== | Roughly 30% of the country's population, are indigenous Pecarians. Most indigenous Pecarians belong to either the [[Quechua people|Runanca]] or [[Aymara people|Andyo]] peoples, who make up 15% and 10% of the country's population respectively. Both the Quepec and Andyo are associated with complex pre-Pecarian civilizations, having been the primary ethnic groups within the [[Tuachec Empire]]. In many rural parts of the country's highlands region, they continue to constitute a majority of the population, and their languages, culture, and traditions remain relatively strong as a result. Another 7% of the Pecarian population is composed of other indigenous groups, including the Hoscos, the Chapoyo, Mayáni and Vajoru, the vast majority of whom are located in the Verde Rainforest. The Pecario Fundación Nacional Aborigen (Pecario National Aboriginal Foundation) estimates that there may also be eight to twelve {{wp|Uncontacted peoples|uncontacted tribes}} located within the Verde rainforest. | ||

=== Religion === | |||

{{bar box | {{bar box | ||

|title= | |title=Religion in Pecario | ||

|titlebar=#ddd | |titlebar=#ddd | ||

|left1= | |left1=Religion | ||

|right1=percent | |right1=percent | ||

|float= | |float=left | ||

|bars= | |bars= | ||

{{bar percent| | {{bar percent|Tacolism|#d4213d|60.0}} | ||

{{bar percent| | {{bar percent|Orthodoxy|gold|12.0}} | ||

{{bar percent| | {{bar percent|{{wp|Atheism|Atheist}}/{{wp|Agnosticism|Agnostic}}|indigo|5.0}} | ||

{{bar percent|Other| | {{bar percent|Atenism|red|8.0}} | ||

{{bar percent|Not | {{bar percent|Other religions|#4997D0|3.0}} | ||

{{bar percent|Not stated|gray|2.0}} | |||

}} | }} | ||

The | The largest religion in Pecario is Tacolic Christianism, which is practiced by 60% of the country's population. Brought by Iberic colonists, and imposed by them on indigenous populations and imported slave labor, Tacolism has been a dominant force in Pecarian society and culture since. The Tacolic Church was a major landholder and provider of public services through the 1800s, and while the church's societal and political role has generally declined since independence, it nonetheless retains a uniquely prominent position within the country. | ||

Adherents of the various {{wp|Eastern Orthodoxy|orthodox}} churches make up 19% of the Pecarian population. While Pecario has long had a small Orthodox population, mostly of [[Lysia|Lysian]] origin, Orthodoxy has grown substantially in the country in the past two decades. | |||

[[File:Catedral Metropolitana de Guayaquil (2283484238).jpg|275px|right|thumb|Santa Borbones Cathedral is one of Pecario's most famous Tacolic churches.]] | |||

Pecarian tacolism is marked by a high degree of {{wp|Religious syncretism|syncretism}}, especially in rural areas, a tendency which emerged from colonial efforts to suppress the religious traditions of the indigenous population. Many Pecarian religious festivals and aspects incorporate rites and iconography from a variety of sources, and the practice of {{wp|folk religion}} in Pecario can vary widely from region to region depending on which cultures and ethnicities influenced the syncretistic process. | |||

Many other religions were brought to Pecario by 19th- and 20th-century immigrants, and retain presences, if comparatively minor ones, within Pecario today. Notably Atenism who encompass roughly 8% of the Pecarian population. Atenic evangelists first arrived in Pecario in the mid-18th century from [[Per-Aten]], establishing missions primarily in the highland regions where indigenous communities were undergoing social and religious transformation. These missionaries sought to introduce Atenism as a bridge between precolonial polytheistic traditions and monotheistic systems, positioning Aten—their solar deity—as a universal god who could resonate with Pecarian cultural cosmology. | |||

Much of the indigenous population adheres to different traditional beliefs marked by inculturation or syncretism with Tacolism. The cult of {{wp|Pachamama|Mamayacha}}, or "Mother Earth", is notable. Deities worshiped in Pecario include Zalanteco, the god of nature and wild animals, Quilla the god od the Mun and the Great Creator of the wurld, and Xihuitl, the goddess of the seasons and the cycle of life. | |||

We can also note the practice of the cult of {{wp|Santa Muerte}}. Descibred as a new religious movement, Santa Murete is a female deity, folk-Tacolic saint and folk saint in Pecarian folk Tacolism and {{wp|Neopaganism}}. Despite condemnation by the Tacolic Church and Evangelical pastors, her cult has become increasingly prominent since the turn of the 21st century. This cult is encouraged by drug cartels, including the [[Santa Polvo Cartel]], which preaches, often violently, the good words of the Santa Muerte to the population. | |||

The | The Constitution of Pecario guarantees {{wp|freedom of religion}} for all residents of the country, explicitly declaring protections for freedom of conscience and worship and for the independence of churches, and establishes the country as a {{wp|secular state}}. | ||

=== | === Education === | ||

In 2007, Pecario was declared free of illiteracy. The education system in Pecario faces many obstacles, in particular the lack of resources and qualified personnel in areas that are difficult to access. | |||

== Culture == | |||

Pecarian culture has been heavily influenced by the Iberic, the Guaruma, the Quepec culturs. The cultural development is divided into three distinct periods: pre-colonial, colonial, and republican. Important archaeological ruins, gold and silver ornaments, stone monuments, ceramics, and weavings remain from several important pre-Colonial cultures. Major ruins include Vunawaku, Tualcacán, El Fuerte de Damoya, Tukavera and Kallanka. The country abounds in other sites that are difficult to reach and have seen little archaeological exploration. | |||

The Iberics brought their own tradition of religious art which, in the hands of local indigenous and mestizo builders and artisans, developed into a rich and distinctive style of architecture, painting and sculpture. The colonial period produced not only the paintings of Diego Vargas, Valentina Sanchez, Rodrigo Ortega, and others but also the works of skilled but unknown stonemasons, woodcarvers, goldsmiths and goldsmiths. A significant body of indigenous religious music from the colonial period has been recovered and has been performed internationally with wide acclaim since 1993. | |||

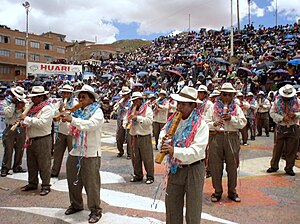

Pecarian has a rich folklore. Its regional folk music is distinctive and varied. The "devil dances" at the annual carnival of Avalrez are one of the great folkloric events of South Alharu, as is the lesser known carnival at El Rosario. | |||

[[File:Chronicles of the New Wurld.png|215px|right|thumb|Cover from the Chronicles of the New Wurld.]] | |||

=== Literature === | |||

The literary production of the [[Tuachec Empire|Tuachec]] period, and of the preceding periods of Pecario's pre-colonial history, is believed to have been primarily {{wp|Oral tradition|oral}} in nature; some have speculated that pre-colonial literature might also be preserved by {{wp|Quipu|quillu}}, though this is a point of contention and, as archaeologists are unsure of how to decipher quillu, cannot be conclusively proven or disproven. The two main genres of pre-colonial work were the ''{{wp|Harawi (genre)|harawi}}'', a form of lyric poetry, and the ''{{wp||hayllo}}'', a form of epic poetry. ''Harawi'' often focused on daily privations and rituals, unrequited love, and personal life, whereas ''hayllo'' tended to relay [[Tuachec Empire#Religion|Tuachec mythology]] and historiography. Much of this pre-colonial literary production has been lost, oftentimes as the result of deliberate destruction by colonial authorities. | |||

During the early years of Iberic colonization, Pecarian literary production consisted primarily of {{wp|Chronicle|chronicles}} detailing the exploration and conquest of the region and documenting local {{wp|flora}}, {{wp|fauna}}, and indigenous peoples. [[Christiano Davegga]], Stillian friar, wrote the ''[[Chronicles of the New Wurld|Chronicles of the New Wurld or the Journey of Diego de Montega]]'' between 1630 and 1647, documenting the appearance of pre-colonial Pecario, the [[Iberic conquest of the Tuachec Empire|Iberic conquest of the Tuachecs]], and the early settlement of the region. Other important Pecarian chroniclers include Bartolomé Velazquez, Amando Encinas and Epifanio Bobadilla. Additionally, indigenous and ''{{wp|Mestizo|mezcla}}'' chroniclers such as Vidal Zamòryno and Efraín Penac worked to record Tuachec mythology, traditions, customs and provide a Tuachec impression of the conquest of Pecario and colonial rule. | |||

[[ | The neoclassical style retained its dominance over Pecarian literature for several decades after independence, reinforced by the admiration of Pecarian revolutionaries for the ancient times notably the [[Aroman Empire]] and melded with a nascent Pecarian nationalism. Many works from this period sought to create a narrative of Pecarian history and identity. Prominent authors and poets of the early republican period include Sergio Ayo and Feliciano Casco. | ||

Beginning in the 1820s, neoclassicism was steadily overshadowed by {{wp|romanticism}}, emblematized by authors and poets such as Silvio Linares and José Gerena, which was in turn overshadowed by {{wp|Realism (arts)|realism}}, represented by the works of individuals including Sebastián Durazo, | |||

Juan Canedo and Cayo Mar. Many works of this period retained the nationalistic influences of the late neoclassical period, | |||

Pecarian | The sociopolitical instability that emerged as a result of {{wp|modernization}} provoked a turn towards {{wp|modernism}} in Pecarian literature. ''{{wp|Indigenismo}}'' and {{wp|social criticism}} were influential trends in Pecarian literature during the early 1900s. Famous authors from this period include Joaquin Vences and Jenaro Fletes. These trends continued into the mid-century, but the rise of the Gòmez regime saw a suppression of non-traditional literary styles and works perceived as dissident. After the deposition of Arturo Gòmez in the Soft Revolution, this censorship was ended, allowing for a return to openness in Pecarian literature and poetry. | ||

=== Art === | === Art === | ||

{{multiple image|perrow = | {{multiple image|perrow = 2|total_width=325 | ||

| align = right | | align = right | ||

| image1 = | | image1 = Sechin Medicine art Peru.jpg | ||

| | | image2 = Peru - Madonna and Child with Bird - Google Art Project.jpg | ||

| | | image3 = Pichincha (1867) Frederic Edwin Church.jpg | ||

| footer = | | image4 = El Yatiri (1918).jpg | ||

| image5 = Alfredo Ramos Martínez, "Florida Mexicana" 2015 19v1.jpg | |||

| image6 = Ismael nery namorados.jpg | |||

| image7 = Art in the General Cemetery of La Paz, Bolivia (5).jpg | |||

| image8 = Colombia´s Transformation II.jpg | |||

| footer = The Pecarian artistic tradition encompasses a variety of movements and styles. | |||

}} | }} | ||

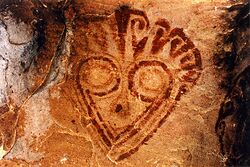

Pecarian art | The Pecarian artistic tradition can trace its origins to painted cave art in the northern caves of Chacaltaya, dating around 7000 years old. The cave paintings depicted handprints, figures, and animals. Further in time, the Lochò culture, saw the development of the first widespread, recognizable artistic style in the region. Much of Lochò art is believed to have been religious in nature, and is known for its complex iconography, frequent depiction of animals, and use of {{wp|contour rivalry}}. The [[Guaruma Empire|Guaruma]] and Chávanan cultures, which succeeded the Lochòs, developed their own unique artistic traditions; the Guarumas are known for their {{wp|Moche portrait vessel|portrait vessels}}, while the Chávanan are known for their painted pottery and vibrant textiles. The Basáy culture, which thrived from the 800 to the 1100 CE, are remembered for their richly-colored textiles and ornate metalwork and inlay, but are perhaps best known for their unique monochromatic pottery, produced by firing clay at high temperatures in a closed {{wp|kiln}}. During the [[Tuachec Empire|Tuachec]] period, the {{wp|Quechua people|Quepec}} and {{wp|Aymara people|Andyo}} synthesized the artistic styles of the cultures that had preceded them, resulting in an explosion of works in a new, eclectic style. | ||

The | Iberic colonization brought the Europan artistic tradition to the region. Pecarian sculpture and painting began to define themselves from the ateliers founded by monks. The [[Iberic conquest of the Tuachec Empire|Iberic domination]] imposed its religious art centered on iconography. In this context, the stalls of the Cathedral choir, the fountain of the Main Square of Santa Borbones both by Polìo de Naguera and Mateo Chiuescio, and a great part of the colonial production were registered. The ornate neoclassical paintings contributed to the aesthetics of the establishment of the rich colonial aristocracy and the grand churches. While the art from the earliest years of colonial period drew primarily from the {{wp|Renaissance art|Renaissance}} styles, Pecarian colonial art is most heavily associated with the {{wp|Baroque}} style, which dominated from the 1600s to the mid-1700s. The {{wp|Cusco School|Santa Borbones School}}, established in 1683, taught Europan artistic techniques in Alharu, which paved the way for the syncretization of Europan and indigenous Alharun styles and the development of a unique artistic tradition. Defining characteristics of the artistic style include a heavy focus on religious subjects, the depiction of local wildlife and landscapes, a lack of perspective, the widespread use of {{wp|metal leaf|gold and silver leaf}} and the application of {{wp|watercolor}} on top of metal leaf to provide a distinctive sheen. Following Pecario's corrigimiento by [[Iverica]], the {{wp|Rococo}} style gained increasing traction within the country. | ||

After Pecario obtained its independence in 1760, there was a turn in the country towards the {{wp|Neoclassicism|neoclassical}} style, as many revolutionaries admired ancient [[Aroman Empire]], whose democratic and republican ideals they considered precedent for their own. Much of the art from the early years of the Pecarian republic was {{wp|history painting}} and {{wp|Portrait|portraiture}} that sought to construct a narrative of Pecarian history and identity. As the 1800s progressed, neoclassicalism was increasingly overshadowed by {{wp|romanticism}} and {{wp|Realism (art movement)|realism}}, a strong nationalistic bent to artwork persisted, however, with works often depicting the country's history, landscapes, and leading figures. Emblematic of this tendency was {{wp|costumbrismo}}, which spanned both romanticism and realism and focused on scenes of everyday life and local traditions in Pecario. | |||

The social instability arising from {{wp|modernization}} provoked an increased interest in non-traditional, transgressive, {{wp|Modernism|modernist}} styles. {{wp|Impressionism}} thrived in the country during the 1880s and 1890s. The focus on Pecarian customs and traditions embodied by ''costumbrismo'' transformed into ''{{wp|indigenismo}}'', which focused primarily on indigenous customs & history and overlapped heavily with the {{wp|Mexican muralism|muralist}} movement. In the early 20th century, the {{wp|Expressionism|expressionist}}, {{wp|Cubism|cubist}}, and {{wp|Surrealism|surrealist}} movements gained traction in the country. [[Victor Maríano]] was the most internationally renowned Pecarian artist and the proprietor of expressionist and surrealist paintings. Many of Maríano's most famous works, such as "Amor Secreto," were influenced by the dark periods of military dictatorships that followed in the 19th or 20th centuries in Pecario. | |||

{{wp|Abstract art|Abstract}} and {{wp|Contemporary art|contemporary art}} spread to Pecario following the 1940s. These movements were suppressed by the authoritarian regimes, which associated them with political radicalism and instead emphasized more traditional artistic styles, but have thrived in the country since the [[Jasmine Revolution]]. | |||

Toaday, with the normalization of violence linked to the War on drugs, urban art rapidly developed in Pecario. One can mention [[Miguel Cruz]], a young urban artist who, through his murals, denounces violence, corruption, consumerism, and pollution. | |||

=== Architecture === | |||

Many of Pecario's pre-colonial civilizations left behind impressive works of monumental architecture which survive into the present. These include the step pyramids of the Lochò civilization, {{wp|Puquios|aqueducts}} of the [[Piura culture|Piura]], megalithic structures of the Guaruma Empire, and {{wp|adobe}} brick structures of the Chávanan culture. [[Tuachec Empire|Tuachec]] {{wp|Inca architecture|architecture}} is among the most significant pre-colonial architecture in Mesothalassa and Alharu, and many examples of it are well preserved. It is known for its {{wp|dry-stone|}} stonemasonry, which has proved remarkably durable, and for the {{wp|Inca road system|road system}} the Tuachecs used to connect their domains. Among the most famous examples of Tuachec architecture are the [[Kallánka]] royal palace and [[Tuyuc Wasi]] temple and the citadel of [[Cùnchalan]]. | |||

[[File:Cathedral of Lima (7521858506).jpg|250px|left|thumb|Pecario is often associated with {{wp|Andean Baroque|Cordillerean Baroque}} architecture.]] | |||

Colonialism saw the {{wp|Renaissance architecture|Renaissance}}, {{wp|Gothic architecture|Gothic}}, and {{wp|Baroque architecture|Baroque}} architectural styles, all well-established in the [[Iberic Empire]], brought over to Pecario. Of these, Baroque architecture predominated, and a local variant known as {{wp|Andean Baroque|Cordillerean Baroque}} developed. Cordillerean Baroque preserved the rich ornamentation of Europan Baroque, but blended it with uniquely Pecarian features, including indigenous motifs, representations of native flora and fauna, and {{wp|Rustication (architecture)|rustication}} modelled after Tuachec stonework. Iberic colonizers also implemented a philosophy of urban planning, placing buildings which invoked Iberic rule - such as {{wp|Presidio|forts}}, {{wp|Mission (station)|missions}}, and {{wp|Church (building)|churches}} - in prominent or central locations to maximize their visibility. | |||

{{wp|Neoclassical architecture}} arrived in Pecario in the 1770s and 1780s, and rapidly became a popular and enduring architectural style; it was sometimes referred to as "Arquitectura República", as it was heavily associated with the newly-established Pecarian Republic. Beginning in the mid-1800s, Pecarian neoclassicism drew increasing influence from the {{wp|Beaux-Arts architecture|Beaux-Arts}} school of architecture, which was itself primarily derived from the principles of [[Lysia|Lysian]] neoclassicism. While some other architectural styles - particularly the {{wp|Gothic Revival architecture|Gothic revival}} and {{wp|Baroque Revival architecture|Baroque revival}} styles - were able to establish themselves in the country during the period, the neoclassical-Beaux-Arts style remained functionally unchallenged as the predominant architectural style in Pecario until the 1930s. | |||

{{wp|Art Deco}} architecture flourished in Pecario during the 1930s and 1940s. {{wp|Modern architecture|Modernism}} and {{wp|International Style (architecture)|internationalism}} began to appear in the country during the eraly 1950s. However, these styles, alongside the subsequent styles of {{wp|Postmodern architecture|postmodernism}} and {{wp|neo-futurism}}, were regarded with suspicion by the authoritarian regimes, which sought to control them and promote more traditional architectural styles, efforts which had at most mixed success. Since the [[Jasmine Revolution]], the {{wp|neomodern}} and {{wp|Contemporary architecture|contemporary}} styles of architecture have become increasingly prominent within Pecario. | |||

=== Music === | === Music === | ||

| Line 762: | Line 795: | ||

=== Cuisine === | === Cuisine === | ||

Pecarian cuisine is known for its diversity, the result of the country's varied geography and its heterogeneous population. Many of the plants typical to {{wp|Spanish cuisine|Iberic cuisine}} were brought by Iberic over several crops, herbs, and animals, including {{wp|wheat}}, {{wp|barley}}, {{wp|rice}}, {{wp|beef}}, {{wp|pork}}, {{wp|Chicken as food|chicken}}, {{wp|Onion|onions}}, {{wp|asparagus}}, {{wp|Beetroot|beets}}, {{wp|Grape|grapes}}, {{wp|dill}}, {{wp|garlic}}, {{wp|coriander}}, {{wp|caraway}}, and {{wp|oregano}}. These foodstuffs and culinary tendencies mixed with those of the {{wp|Inca cuisine|Tuachecs}}, who had their own, centuries-old culinary tradition. Native crops such as {{wp|potatoes}}, {{wp|Maize|corn}}, {{wp|quinoa}}, beans, {{wp|cassava}}, {{wp|chili peppers}}, and {{wp|caigua}} quickly became integrated into the cuisine of Iberic settlers, while some other native crops - such as {{wp|oca}}, {{wp|ullucu}}, {{wp|mashua}}, {{wp|tarwi}}, and {{wp|maca}} - persisted mainly among indigenous populations. The country's cuisine also features a great variety of tropical fruits (including {{wp|bananas}}, {{wp|plantains}}, {{wp|Orange (fruit)|oranges}}, {{wp|pineapples}}, {{wp|mangoes}}, {{wp|guavas}}, and {{wp|papayas}}), nuts (such as {{wp|cashews}}, {{wp|peanuts}}, and {{wp|Brazil nut|Manamanan nuts}}), and other agricultural products (including {{wp|coffee}}, {{wp|chocolate}}, and {{wp|sugar}}). | |||

[[File:Bandeja paisa 30062011.jpg|275px|right|thumb|''{{wp|Bandeja paisa}}'' is sometimes regarded as Pecario's {{wp|national dish}}.]] | |||

Breakfast (Iberic: ''Desayuno'') is typically the largest meal of the day in Pecario, with lunch (''Almuerza'') only slightly smaller and dinner (''Cena'') typically the lightest meal. | |||

The | There are numerous regional variations within Pecarian cuisine. The cuisines of the coastal regions and the country's islands have a traditional bent towards the use of {{wp|poultry}} and {{wp|seafood}}, while the cuisine of the highlands region tends to rely more heavily on native crops and animals, and the cuisine of the hinterlands places greater importance on {{wp|red meat}}, often grilled or smoked. | ||

''{{wp|Bandeja paisa}}'' ("{{wp|Bandeirantes}}'s breakfast"), a breakfast dish consisting of red or black beans, white rice, ground meat or sausage (such as {{wp|chorizo}}, {{wp|linguiça|}}, or {{wp|botifarra}}), a fried egg, a piece of fried plantain, {{wp|hogao}}, and a {{wp|arepa}}, is sometimes considered to be the Pecarian {{wp|national dish}}. Other dishes regarded as distinctly Pecarian include {{wp|empanada}}, fried turnovers filled with meat, vegetables, and cheese; ''{{wp|Papa a la huancaína}}'', sliced boiled potatoes topped in a spicy cream sauce; ''{{wp|Lomo a lo pobre}}'', beef tenderloin served with a fried egg and french fries; ''{{wp|Rocoto relleno}}'', spicy red peppers stuffed with ground meat and cheese, fried in egg batter or masa, and topped with cheese; and ''{{wp|Ají de gallina}}'', a stew prepared with chicken, onion, garlic, yellow peppers, cheese, and bread soaked in evaporated milk. | |||

Dishes traditional to the {{wp|Quechua people|Quepec}} and {{wp|Aymara people|Andyo}} include {{wp|carapulcra}}, a stew of meat, {{wp|chuño}}, peanuts, peppers, garlic, and cloves, sometimes served with rice or cassava; ''{{wp|olluquito}}'', ulluco served with diced pieces of {{wp|anticucho}}, skewered and grilled cubes of meat, commonly seen today as street food, and {{wp|humita}}, {{wp|masa}} stuffed with sweet or savory items and then boiled in a cornhusk. | |||

[[File:Glorious Coffee 1 (147187619).jpeg|250px|left|thumb|Pecario is known internationally for its coffee.]] | |||

Popular or emblematic desserts in Pecario include {{wp|buñuelo}}, fritters covered in sugar and cinnamon and sometimes filled with cheese, jam, or syrup; {{wp|quindim}}, a custard dessert made with shaved coconut, known for its bright yellow color; {{wp|guava jelly}}, confections made from guava pulp and cane sugar; and ''{{wp|Suspiro de limeña|Suspiro de lemoña}}'', a dessert made of {{wp|pannacotta}} or {{wp|dulce de leche}} topped with meringue and flavored with vanilla, cinnamon, and port. | |||

Pecario | {{wp|Coffee}} is widely considered to be the Pecarian national beverage, and is typically served with milk or cream and sugar. {{wp|Hot chocolate}}, {{wp|Chicha morada}} (a beverage prepared from purple corn), {{wp|Chapo (beverage)|Chapo}} (a drink made from bananas or plantains, spiced with cinnamon and cloves), {{wp|Guarapo}} (fresh sugarcane juice), and {{wp|Cholado}} (a beverage made of shaved ice, condensed milk, and fruit juice or syrup) are also popular within the country. Certain domestic Pecarian soft drink brands, most famously {{wp|Inca Cola|Tuachec Kola}} and {{wp|Kola Inglesa|Pècha Kola}}, have managed to retain their prevalence within the Pecarian market in spite of fierce competition from international challengers. | ||

The most popular type of alcoholic beverage in Pecario is {{wp|beer}}. Pecario is also known for {{wp|rum}}, particularly its light and amber rums. Other alcoholic beverages that are from or widely consumed in Pecario include {{wp|chicha}}, an indigenous alcoholic beverage typically prepared using corn, {{wp|pisco|}}, a local form of {{wp|brandy}} and {{wp|cachaça}}, a distilled spirit made from sugarcane juice. | |||

{{Gallery | |||

|title= | |||

|width=180 | height=160 | |||

|align=center | |||

|footer= | |||

|File:Aji de gallina 10.jpg | |||

|alt2=A plate of yellow chicken stew served with rice and boiled eggs. | |||

|Ají de gallina is considered a Pecarian comfort food. | |||

|File:Anticuchos - Grilled Beef Heart skewers.jpg | |||

|alt3=Popular street food in Pecario. | |||

|Anticucho is a popular street food in Pecario. | |||

|File:Vatapá.jpg | |||

|alt2=A plate of Vatapá | |||

|Vatapá is typical of the country's islands. | |||

|File:Suspiro limeño.jpg | |||

|alt6=A cocktail glass filled with caramel-colored dessert. | |||

|Suspiro de lemoña served in a glass. | |||

}} | |||

===Language=== | |||

Iverican is the most spoken official language in the country, according to the 2003 census; as it is spoken by two-thirds of the population. All legal and official documents issued by the State, including the Constitution, the main private and public institutions, the media, and commercial activities, are in Iverican. Although the first settlers were mostly of [[Iberic Diaspora|Stillian]] origin, after the signing of the [[Treaty of Gorgia]], the arrival of many Iveric immigrants transformed the Pecarian language. Some regions have however strongly kept Stillian roots, mixing with Iverican and creating a unique dialect of Stillian Iverican. If we can talk of an Iverican language in Pecario, we can note that it is a great mixture of Native, Stillian and mainly Iverican roots. | |||

In spite of the predominance of Iveric, many other languages are spoken within Pecario. The {{wp|Quechuan languages|Quepec language}} is the largest indigenous language within the country, was the ''lingua franca'' of the [[Tuachec Empire]], and remains the mother tongue in some majority-indigenous rural areas, though the exact number of speakers is unknown, estimates vary widely between sources. Quepec is typically divided into three dialects, of which {{wp|Southern Quechua|Southern Quepec}} is the largest and most prominent. The {{wp|Aymara language|Andyo language}}, while not as widespread as Quepec, also remains the mother tongue in some regions of the country. Quepec and Andyo have received some degree of recognition from the Pecarian government, education in Quepec and Andyo is permitted in those regions of the country where they are the primary language and public broadcasters are required to provide Quepec and Andyo subtitling for their broadcasts. Several smaller indigenous languages can also be found in Pecario, though few of these have any recognition or use beyond the confines of indigenous reservations. | |||

{{wp|French language|Lysian}} is a language spoken extensively in the Costa Esmeralda region, especially in the center of [[San Luis (Pecario)|San Luis]]. Originally brought by the Lysian settlers founding the colony of [[Côte d'Émeraude]], the language experienced a revival during the 19th century, notably with the efforts of Amélie Dubois, an activitist from San Luis, who fought for the survival of the Lysian language. Furthermore, the arrival of numerous immigrants from [[Florentia]], fleeing the economic crisis, at the beginning of the 20th century also contributed to strengthen the Lysian language in the region. | |||

Several languages have also been brought to Pecario by immigrants, {{wp|Italian language|Mantellan}} and {{wp|Arabic language|Per-Aten language}}. Communities speaking immigrant languages such as these persist in some rural areas and immigrant neighborhoods, but, generally speaking, the presence of these languages in Pecario has faded due to the assimilation of immigrant communities into mainstream Pecarian culture. | |||

===Theater and cinema === | |||

{{multiple image|perrow = 2|total_width=400 | |||

| align = right | |||

| image1 = universo cinema.png | |||

| image2 = Bajo el cielo.png | |||

| footer = Universo Cinema is one of the oldest continuing film companies producing iconic films such as the pictured 1930s ''Noche en San Luis''. | |||

}} | |||

Theater in Pecario has its roots in the Tacolic missionary era, when performance was used as a tool for religious instruction. These early efforts focused on biblical stories and morality plays, performed in makeshift stages in mission villages. However, with the establishment of the Iveric Corrigimiento, Pecario experienced a cultural blossoming. By the early 18th century, secular theater gained traction, with playwrights blending indigenous narratives and colonial themes. This period also saw the emergence of Pecarian opera. The most celebrated example is "Los Ríos que Cantan", composed by Valerio Tomás in 1839, which explores the fusion of local myths and universal human struggles. Other notable figures include Dominga Altamirano, who revolutionized {{wp|libretto|libretti}} by incorporating indigenous languages into her operas, and Rodolfo Cárdenas, a pioneer of grand romantic productions. The 19th century also gave rise to teatro campesino ("peasant theater"), where barn stages hosted vibrant dramatizations of folk tales and local legends. These plays often carried subtle critiques of colonial authority and celebrated Pecario’s diverse cultural heritage. | |||

By the 20th century, Pecarian theater transitioned to modern forms, emphasizing musicals, social dramas, and political allegories. During the authoritarian Gòmez regime (1971–1999), theater became a subtle battleground for dissent. Works like "La Última Tormenta" (The Final Storm) and "Cenizas de la Libertad" (Ashes of Freedom) criticized government oppression under the guise of historical narratives. Despite heavy censorship, playwrights such as Eugenio Arrieta and María Constanza Villegas found ways to reflect the struggles of ordinary Pecarians. After the Jasmine Revolution, theater flourished again, with a new generation of playwrights like Jimena Huerta and Álvaro Lamas addressing themes of environmental justice, gender equity, and indigenous rights. | |||

Cinema arrived in Pecario at the dawn of the 20th century, with the first public screening using a cinematograph in Villa Hermosa in 1902. The first Pecarian film, "El Rescate del Jaguar" (The Jaguar's Rescue), was produced in 1911, showcasing a story rooted in local folklore. Pecarian cinema truly found its footing between the 1930s and 1940s being remembered as the golden age of national film. Iconic movies such as "El Río Silencioso" (The Silent River) and "Viento Bajo las Alas" (Wind Beneath the Wings) gained international acclaim for their poetic storytelling and visual innovation. The Gòmez era saw heavy censorship, favoring propaganda films like "Corazón y Bandera" (Heart and Flag) and sanitized comedies such as "La Fiesta del Pueblo" (The People's Party). However, the Nuevo Cine Pecariano movement of the 1980s emerged in defiance. Directors like Rubén Yaraví and Elena Torrealba used metaphor and symbolism to critique the regime. Films such as "Sombras en el Río" (Shadows on the River) and "El Espiral Infinito" (The Infinite Spiral) are considered masterpieces of this era. | |||

The collapse of the regime ushered in a cinematic renaissance. Modern Pecarian films, such as "Los Caminos de Sal" (Paths of Salt) by Ana Beltrán and "El Eco de las Montañas" (Echo of the Mountains) by Rodrigo Cruz, have gained acclaim for their focus on social justice and environmental themes. Directors like Lucía Narváez and Santiago Huamán continue to push the boundaries of storytelling, blending modern techniques with deeply rooted cultural narratives. | |||

=== Sports === | === Sports === | ||

The most popular sport in Pecario is {{wp|soccer}}. It is believed to have first arrived in the country in 1870, however, the sport did not begin to gain popularity in Pecario until the 1890s, with soccer teams rapidly proliferating during the 1900s and 1910s and a national team being officially organized in 1925. The country's governing body for soccer is the Pecarian Soccer Federation, which was founded in 1922 and manages both the country's national team and the Pecarian Pro League. | |||

{{wp|Basketball}} first arrived in Pecario in the 1920s. It gained popularity rapidly after the end of the war, particularly in Pecario's growing urban areas. The country's men's national team was organized in 1940, and its women's national team was formed in 1950. Aucuria's governing body for professional basketball is the Pecarian National Basketball Association, founded in 1951, which operates both the men's and women's domestic basketball leagues. | |||

Like basketball, {{wp|baseball}} arrived in Pecario in the 1920s. The Pecarian Baseball League was organized in 1937; its annual {{wp|championship}} is the Pecarian Series. | |||

[[File:5 Etapa-Vuelta a Colombia 2018-Ciclista en el Peloton 1.jpg |250px|right|thumb|Cyclists during the 2019 edition of the Tour of Pecario.]]{{wp|Cycle sport|Cycling}} began to gain popularity in Pecario with the 1948 establishment of the Tour of Pecario, a multi-stage road race; the country is particularly famous for producing talented climbers and puncheurs as a result of its natural terrain. Pecarian cyclists first obtained widespread international recognition in the 1960s and 1970s with the accomplishments of Pepito Parrilla, Celio Casal and Román Pedroza. The country is also notable for its accomplishments in women's {{wp|track cycling}}. | |||

{{wp|Competition climbing}} is a very popular sport in Pecario. Given its natural landscape, Pecarians have always enjoyed climbing. At the Eurth Olympic Games, the Pecarians are always on the podium. We can cite, famous Pecarian climber Lucio Falla who won a gold medal 4 times in a row at the Eurth Olympic Games in 2008, 2012, 2016 and 2020. | |||

Other sports with professional leagues or governing associations in Pecario include {{wp|volleyball}} (Pecarian National Volleyball League}, {{wp|tennis}} (Pecarian Tennis Federation), {{wp|racquetball}} (Pecarian Confederation for Racquetball and Squash), and {{wp|rugby league}} (Pecarian Rugby League Association). {{wp|Track and field}} sports, {{wp|Olympic weightlifting|weightlifting}}, {{wp|winter sports}} (particularly {{wp|skiing}}), {{wp|martial arts}} (particularly {{wp|boxing}} and {{wp|taekwondo}}), {{wp|Sailing (sport)|sailing}}, and {{wp|Shooting sports|shooting}} all have some presence in Pecario. The country has also produced a handful of notable chess players, including Vicente Tierno and Martín Arjona. {{wp|Chaza}} is a sport of indigenous origin in which two teams of four players hit a ball with their hands or a racket, scored similarly to tennis. | |||

===Holidays=== | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="width:100%" | |||

|- | |||

! scope="col" style="width: 10%;" |Date | |||

! scope="col" style="width: 15%;" |Anglish name | |||

! scope="col" style="width: 15%;" |Pecarian name | |||

! scope="col" style="width: 10%;" |Day off | |||

! scope="col" style="width: 70%;" |Notes | |||

|- | |||

|January 1 ||{{wp|New Year’s Day}} ||'' Año Nuevo'' ||{{ya}} ||Marks the first day of the {{wp|Gregorian calendar}} year. | |||

|- | |||

|January 16 ||Independence Day||''Independencia'' ||{{ya}} ||Celebrates Pecario's declaration of independence from [[Iverica]]. | |||

|- | |||

|''variable'' ||{{wp|Ash Wednesday}} ||''Miércoles de Ceniza'' ||{{na}} ||Marks the beginning of {{wp|Lent}}. | |||

|- | |||

|February 25 |||Day of Discovery||''Descubrimiento'' ||{{ya}} ||Celebrates the arrival of [[Diego de Montega]] and Stillian {{wp|conquistador}} in Pecario. | |||

|- | |||

|April 7 ||Liberty Day ||''Libertad'' ||{{ya}} ||Celebrates the ratification of the Declaration of the Rights of the People. | |||

|- | |||

|''variable'' ||{{wp|Good Friday}} ||''Santò'' ||{{ya}} ||Commemorates the {{wp|Crucifixion of Jesus}}. | |||

|- | |||

|''variable'' ||{{wp|Easter}} ||''Pascua'' ||{{ya}} ||Celebrates the {{wp|Resurrection of Jesus}}. | |||

|- | |||

|May 1 ||{{wp|International Workers' Day|Labor Day}} ||''Trabajo'' ||{{ya}} ||Celebrates the international {{wp|labor movement}} and the Pecarian working class. | |||

|- | |||

|''first Sunday in May'' ||{{wp|Mother's Day}} ||''Amor Materno'' ||{{ya}} ||Celebrates Pecarian mothers and motherhood. | |||

|- | |||

|''variable'' ||{{wp|Pentecost}} ||''Espíritu Santo'' ||{{na}} ||Celebrates the descent of the {{wp|Holy Spirit}} upon the {{wp|Apostles in Christianity}}. | |||

|- | |||

|''first Sunday in June'' ||{{wp|Father's Day}} ||''Amor Paterno'' ||{{na}} ||Celebrates Pecarian fathers and fatherhood. | |||

|- | |||

|June 24 ||{{wp|Saint Jonas's Festival}} ||''Fuego Sagrado'' ||{{ya}} ||Celebrates the {{wp|nativity of Saint John the Baptist}} and the {{wp|summer solstice}}. | |||

|- | |||

|August 15 ||{{wp|Assumption of Mary|Assumption}} ||''Asunción'' ||{{na}} ||Celebrates the ascension of the {{wp|Mary, mother of Jesus|Virgin Mary}} to Heaven. | |||

|- | |||

||August 17 ||Flag Day||''Bandera'' ||{{na}} ||Commemorates the creation of the Pecarian flag. | |||

|- | |||

|''last Monday in September'' ||Remembrance Day ||''Kuyana Recuerdo'' ||{{na}} ||Commemorates all persons who died fighting for liberty in Pecario. | |||

|- | |||

|November 1 ||{{wp|All Saints' Day}} ||''Santos Eternos '' ||{{ya}} ||Commemorates all Tacolic saints, known or unknown. | |||

|- | |||

|December 25 ||{{wp|Christmas|Nativity}} ||''Navidad'' ||{{ya}} ||Celebrates the {{wp|Nativity of Jesus}}. | |||

|- | |||

|December 31 ||{{wp|New Year's Eve}} ||''Pachakuti'' ||{{ya}} ||The day preceding New Year's Day. | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

{{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

{{Pecario}} | |||

{{Eurth}} | {{Eurth}} | ||

[[Category:Pecario]] | [[Category:Pecario]] | ||

Latest revision as of 19:17, 18 December 2024

Republic of Pecario República de Pecario | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Unidos en la diversidad, juntos hacia el futuro." "United in diversity, together towards the future" | |

| Anthem: Himno Nacional Pecariano National anthem of Pecario | |

National cockade | |

Location of Pecario | |

Map of Pecario | |

| Capital | Santa Borbones |

| Largest | Valleluz |

| Official languages | Iverican, Stillian |

| Recognised national languages | Iverican, Stillian Iverican, Stillian, Quepec, Andyo, other indigenous languages |

| Demonym(s) | Pecariano, Pecarian |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

• President | Andreas Lineria |

• Vice President | Gabriel Valdez |

• President of the Senate | Carlos Rojas |

| Legislature | Congress |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Representatives | |

| Independence | |

• Declared | 1752 |

• Recognized | 1766 |

| Area | |

• | [convert: invalid number] |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | 22,658,480 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | $200 billion |

• Per capita | $9,995 |

| Gini | 0.38 low |

| HDI | 0.800 very high |

| Currency | Pecarian pesos |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Alharun Central Time) |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy BCE/CE |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +39 |

| Internet TLD | .pco |

Pecario, officially known as known officially in Iverican as La República de Pecario, concisely as the Republic of Pecario, and informally as Pecario, is a sovereign state in Alharu on Eurth. It is bordered on the South by Manamana. The seat of government is Santa Borbones, which contains the executive, legislative, and electoral branches of government,it is also the constitutional capital and the seat of the judiciary. The largest city and principal industrial center is Valleluz.

The sovereign state of Pecario is a constitutionally unitary state, divided into nine departments. Its geography varies from the peaks of the Cordillera del Sol in the North, to the eastern lowlands. A third of the country is in the mountain range. The country's population, estimated at 22 million, is multi-ethnic, including natives, mestizos and europans (mainly Ivericans). Iverican is the official and predominant language, although 36 indigenous languages also have official status, the most commonly spoken of which are quepec, aymaro and guaruma.

The history of Pecario begins with the dominance of the Tuachec Empire in the 15th century, followed by the Iverican conquest in the 17th century. After uprisings, the country gained independence in 1753. The 19th century was marked by political instability, but also by progress in education and civil rights. In the 20th century, periods of military control alternated with democratic governments, seeking to combat corruption and inflation. In 2002, an unprecedented economic crisis struck, leading to the resignation of President Eduardo Chapo. Luis Mesa came to power in 2006, ushering in a calmer period until 2019. The Santa Polvo Cartel emerged in 2010, taking control of the drug trade leading to a drug war. President Mesa will resign in 2019 after a scandal related to the Santa Polvo cartel, he will be replaced by Andreas Lineria. Today the country is one of the most corrupt state in the wurld, the government of Presidente Lineria is completely under the orders of the cartel and pretends not seeing the recurring massacres in the country. In 2020, the country was classified as a Narco-State due to the Pecarian government turning a blind eye towards drug cartels. Today, Pecario is plagued by corruption and violence related to drug trafficking.

Etymology

When Stillian conquistadors first disembarked on the shores in the early 16th century, they nicknamed the land Nueva Stillia, in homage to their homeland’s legacy within the former Iberic Empire. This name, however, would not endure long.

During their initial contact with the indigenous Tuachec people, the explorers learned that the locals referred to the land as Pecàriacha, a word in the ancient Quepec language that translates to “land of the Pecario.” The Pecario was no ordinary animal; it referred to the revered jaguar, a sacred creature in Tuachec cosmology. To the Tuachec, the jaguar symbolized strength, courage, and the divine connection between the heavens and the earth. They believed the spirit of the Pecario watched over their people and the land, and their legends often depicted the jaguar as a guardian of the forests and rivers.

The Stillian explorers quickly adopted the term. Additionally, the arrival of numerous Iberic immigrants who were not of Stillian origin influenced the settlers’ perception of the land’s identity. Seeking unity among the diverse populations of the burgeoning colony, the authorities embraced the name Pecario as a unifying symbol.

Following the conquest of the Tuachec Empire, the Kingdom of Pecario was officially established in 1634, cementing the name’s usage. It became a name used by all, representing both the land’s indigenous roots and its colonial legacy.

History

Prehistory and Tuachec period

The earliest evidences of human presence in Pecarian territory have been dated to approximately 12,500 BCE with human remains and stone tools in the Vallejo valley providing some of the earliest discovered evidence of human habitation in Mesothalassa. The domestication of the potato occurred in Mesothalassa some time between 8,000 BCE and 5,000 BCE; the cultivation of corn spread to the region between 5,000 and 4,000 BCE, and the domestication of quinoa occurred in roughly 2,000 BCE. Early Pecarian societies also domesticated the llama, alpaca, and guinea pig in Pecario in roughly 6,000 BCE. They carved into rocks many petroglyphs throughout the country, notably those located in San Cristóbal. Organization relied on reciprocity and redistribution because these societies had no notion of market or money. The oldest known complex society in Pecario, the Lochò civilization, flourished along the coast of the Manamana Bay between 3,000 and 1,800 BCE. These early developments were followed by archaeological cultures that developed mostly around the coastal and moutainous regions of the Cordillera del Sol throughout Pecario. The Pùchique culture which flourished from around 1000 to 200 BCE along the western coasts of Pecario was an example of early pre-Tuachec culture.

Traces of Sjådska presence dating back to 320 BCE on the banks of Manamana Bay attest to an active passage of this people. No physical structure has been discovered, but the discovery of an Útskip wreck near Marelia suggests that the Sjådska used the bay for trading and travel. It is likely that they traded and maintained good relations with the tribes present in the territory.

The first real datable civilization, Guaruma civilization which had its capital at Guaruma, emerged in the east of Pecario. The capital city of Guaruma dates from as early as 100 CE when it was a small village based on agriculture. The Guaruma community grew to urban proportions between 700 CE and 900 CE, becoming an important regional power in Mesothalassa. Guaruma sites are marked by the presence of central pyramids and monoliths, irrigation systems, and terraced farms. As the rainfall decreased, the surplus of food decreased, and thus the amount available to underpin the power of the elites. The Guaruma civilization disappeared around 900 CE.

The Guaruma civilization was succeeded by the Chávanan culture, which thrived from 1,000 to 1,200 CE. The Chávanan people developed more sophisticated systems of irrigation and social stratification, as well as more refined masonry, textiles, and metalworking of copper and gold, and the first recognizable artistic style. Following its decline and collapse, the Chávanan culture was succeeded in western Pecario by the Lóscos and in South-east Pecario by the Tomóto, both of which existed roughly from 100 CE to 800 CE. The Lóscos are famous for their vibrant works of pottery, patterned textiles, and ornate metalworking, while the Tomóto are known for their construction of Geoglyphs and monumental structures. Unknown troubles, likely related to civil wars according to recent studies, in the 9th century led to the collapse of both cultures and the rise of the Basáy culture, thrived from the 800 CE to the 1100 CE and oversaw a further flourishing of textiles, metalwork, and monumental construction, as well as the development of pottery and large murals. The disappearance of the Basay culture in the 1100s corresponds with the appearance of groups clearly identifiable as the Quepec and Andyo peoples.

In the 14th century, the Tuachec, of Quepec origin, emerged as a powerful state which, in the span of a century, will form the largest empire in Mesothalassa with their capital in Tualcacán. The Tuachec is known to have existed historically by 1250, and, in the subsequent decades, came to control a large area of Northern Pecario. The Tuachecs participated in a confederation with other city-states, initially holding a subordinate rather than dominant position. Under Llóque Hanpaqui, they strengthened their position within the confederation. Thus, upon the death of the last chief of the Confederation, Hupac Yanqui seized control of the confederation, and the Tuachecs imposed their laws on all tribes. This rapid expansion worried several city-states. His successor, Rascar Chalec, was not as successful, and a conspiracy ended his reign. But around 1400, the Tuachecs resumed their expansion under Huayna Cápac. With Huayna Cápac, the Tuachecs solidified its dominance over the region and expands its territory.Gradually, as early as the thirteenth century, they began to expand and incorporate their neighbors. Tuachec leadership sent envoys to cities and towns encouraging them to become members of the empire in exchange for luxury goods and local elites being allowed to retain their titles. Cities which refused to join willingly were conquered and plundered, with local leadership deposed or executed and replaced by loyal nobles. Tuachec expansion was slow until about the middle of the fifteenth century, when the pace of conquest began to accelerate, particularly under the rule of the emperor Pómatec. Under his rule and that of his son, Pómatec Capac II, the Tuachec came to control the majority of Western Mesothalassa by the 1500s, with a population of 10 to 15 million inhabitants under their rule. Pómatec I also promulgated a comprehensive code of laws to govern his empire, while consolidating his absolute temporal and spiritual authority as the God of the Moon. The official language of the empire was Quepec, although hundreds of local languages and dialects were spoken. The Tuachec leadership encouraged the worship of Quilla, the moon god and imposed its sovereignty above other cults.The Tuachec considered their King, the Vagra Tuachec, to be the "child of the moon". We also owe them the Tuachec Roads, a vast road network linking the regions of the empire to the capital city. It served as an economic and political integrative axis.

Conquest and colonial period

When Pómatec IV, the last Tuachec emperor, became emperor in 1629, he inherited an empire weakened by a long famine and divided by quarrels of bellicose nobles. In October 1630, Stillian conquistador Diego de Montega landed with his men on the coast of Pecario. He is one of the migrants who was part of the Gran Viatge fleeing the Iberic Empire. He landed in the Bahía del Fuego Sereno. He nicknamed the land Nueva Stillia, in homage to their homeland’s legacy within the former Iberic Empire. He quickly established the first Iberic fortified settlement in Mesothalassa named Puerto Montega.

In early 1631, Diego de Montega met with envoys sent by Pómatec IV, who invited him to Tawantinsuyo. Diego de Montega made the trip, accompanied by 1'500 men. In addition to meeting the Tuachec Emperor, Montega met envoys from leaders of rebellious cities that resented Tuachec dominance. Montega agreed to aid them in a rebellion against the Tuachecs. After defeating an important Tuachec forces at Tawantinsuyo where Montega's forces captured Emperor Pomatec IV, the Tuachec emperor became a hostage of Montega and his troops.

During that period, the area of Manamana Bay was first explored by the Iberic conquistador Sebastián de Salcázaro and his men. In July 1632, the inlet of San Cristobal was first sighted by the Iberics. A landing party went ashore on 25 July 1632, on the day of the feast of San Cristóbal. He completed the conquest of the last places of Tuachec resistance in Manamana aided by Hosco rebels. Despite strong resistance from some generals of Pòmatec IV, including Yuñahi, Manamana was conquered between 1632 and 1633. Sebastián de Belalcázar founded San Cristobal on 4 April 1633, on the ruins of a Tuachec city, which Yuñahi had destroyed before abandoning it to the Iberics. The Iberics subsequently executed the emperor on 13 June 1633 believing it would make the other Tuachec forces to surrender. Contrary to the predictions of Montega's officers, the death of their emperor encouraged the Tuachec troops to total war, multiplying ambushes and avoiding frontal engagements with the Iberic troops. Following this, the Iberic forces seized and brutally sacked Tualcacán the Tuachec capital on 19 September 1633. The fall of the empire's heart led to the submission of most Tuachec forces.

In 1634, the Kingdom of Pecario was officially proclaimed, with its capital at Santa Borbones and with the conquistadors installing Inti Yupanqui as a puppet emperor on the throne. The conquistadors continued to suppress the remaining Tuachec resistance and the conquest of the former Tuachec Empire's territory. Following this, the Iberics conquered and plundered their former native allies, seeking to ensure their total control over the region. By 1650, the Iberic conquest of the Tuachec Empire was complete and the Northern part Manamana was under Iberic control. The last Tuachec resistance was suppressed when the Iberican annihilated the Neo-Tuachec State in Tuyuq Wasi in (1652.

La Gran Peregrinación

The fall of the Tuachec Empire led to a significant political upheaval that reverberated beyond borders and into Alharu. Some settlers extolled, through texts and letters addressed to the Iberic Empire, describing news that the colony was rich in gold and silver. It triggered a flood of fortune-seekers, who increased the newfly kingdom's population and expanded its frontiers. This resulted in several waves of migration to the kingdom of Pecario, particularly in the years 1645 and 1650, where the influx of settlers was so significant that some cities had to turn people away. As the mayor of Valleluz, Pedro Alcazar de Guantaneo, wrote in 1647: "Thus, we saw a moving tide arriving, pressing at the gates of the city. The soldiers struggled to contain them. Women, children, and men eagerly awaited the opportunity to settle and cultivate the vast surrounding lands. There was, of course, a sense of disdain from the "old" settlers towards the newcomers. A man remains a man even in the face of his peers."

Thus, the population of settlers quadrupled within 30 years. By 1700, the Iberic population was estimated at 800,000, and it continued to climb until stabilizing in the mid-20th century. In the 1670s, king Francisco Perez reorganized the country with gold and silver mining as its main economic activity and native forced labor as its primary workforce. With the discovery of the great silver and gold lodes at San Marañón, the kingdom flourished as an important provider of mineral resources. With the conquest started the spread of Tacolism; most people were forcefully converted to Tacolism, with Iberic clerics believing that the Native Peoples "had been corrupted by the Devil". It only took a generation to convert the population. They built churches in every city and replaced some of the Tuachec temples with churches, such as the Quilla Temple in the city of Santa Borbones. The church employed the Inquisition, making use of torture to ensure that newly converted Tacolics did not stray to other religions or beliefs, and monastery schools, educating girls, especially of the Tuachec nobility and upper class. Pecarian Tacolism follows the syncretism, in which religious native rituals have been integrated with Tacolic celebrations. In this endeavor, the church came to play an important role in the acculturation of the Natives, drawing them into the cultural orbit of the Iberic settlers.

To further encourage settlement, the Iberic authority used native forces as slaves through the Encomienda system, in which the settlers, were granted indigenous people to use as forced laborers and to educate in the Iberic language and Tacolic religion. This system proved immensely lucrative and the colony quickly became a major producer of cash crops such as sugarcane, coffee, and Cacao. The natives were subjected to severe persecution by the colonizers. They endured numerous unjustified massacres, land and resource dispossession, as well as intense economic exploitation. These combined factors led to a rapid decline in the indigenous population, weakening individuals physically, disrupting their social and economic systems, and introducing destabilizing psychological and cultural pressures. By 1730, the indigenous population was recorded at 5 million compared to approximately 14 million in 1640. The severe abuses associated with the Encomienda system led to several native rebellions against Iberic in the 17th and 18th centuries, with the most significant - and the last major one - episode being that of Juan Santos Pomatec in 1732, always with the thwarted goal of restoring the territory of the empire. Seeking to further expand Pecario's population, the royal government tacitly permitted intermarriage between white settlers and indigenous women in 1704. A caste system developed in the colony, with pies embarrados (Europans born in Mesothalassa) at the top, pies dorados (Europans born in Europa) below them, mezcla (individuals of mixed race or ethnicity) below them, and indigenous Alharun at the bottom. With the growth of local institutions, the kingdom's increasingly large pies embarrados and mezcla populations began to develop a uniquely Alharun identity.

Conquest (1687-1689)

The Kingdom of Lysia, drawn by the riches that the Iberics had discovered, sent colonists to Mesothalassa. This expedition led to the establishment of the colony of Côte d'Émeraude in 1633 to the West of the newly founded Kingdom of Pecario.

By 1680, Pecario had experienced exponential growth and undergone a significant demographic boom due to La Gran Peregrinación. The kingdom then began to seek expansion of its borders and looked eastward. Brief diplomatic exchanges were made between the Lysian governor and Pecarian diplomats, but nothing was officially signed, with the burning question of borders left unanswered. In 1686, King Gilete de Orozco of Pecario, frustrated by the situation, issued an ultimatum to the colony: the Lysians must unconditionally cede a large valuable parts of their colony to the kingdom in order to hope for signing a non-aggression pact and normalizing relations between the two states. The Pecario general staff knew perfectly well that the request would be denied and were actually only looking for a pretext to start a conflict with the colony. Lysian colonial governor Charles de la Roncière formally refused, and thus the Kingdom of Pecario officialy declared war on the colony in March 1687.

The first real battles began in April 1687. Pecario’s numerical and military superiority greatly disadvantaged the colony of Côte d'Émeraude. Colonial diplomats desperately tried several times to request reinforcements from the mainland in Europa, but the Lysian aristocracy gradually lost interest in the matter and preferred to leave the colonists to their fate. A military expedition was deemed too costly and unprofitable. Despite a few vain heroic Lysian victories, the colony’s capital, Saint-Louis, fell into the hands of Pecarian troops in November 1687. The Lysian colonial administration officially surrendered in November 1688. The rest of the territory was fully occupied afterward, although pockets of Lysian resistance persisted until December 1688.

The Treaty of Saint-Louis was signed thereafter, named after the location where it was drafted, and effectively resulted in the annexation of the entire colony of Côte d'Émeraude into the Kingdom of Pecario. Colonists were given the choice to either remain on their lands or leave the territory to try to reach the nearest Lysian colony, Florentia. Most chose to leave the colony, but a minority opted to stay. They formed a community of Lysians centered around Saint-Louis (renamed San Luis after the conflict). The Lysian community of San Luis deeply influenced the city's style and culture. This community still exists to this day.

Iveric corregimiento (1717-1752)

In 1717, the Kingdom of Pecario, faced a critical juncture in its history. Years of internal chaos, including royal succession disputes and civil strife, had weakened the kingdom to the brink of collapse. The powerful noble families, such as the House of Galdona and the House of Virelia, clashed over the throne, leading to widespread instability. Faced with the threat of disintegration, King Leovigildo II, the reigning monarch, and his court turned to the nearby Iveric Republic for help. This marked the beginning of diplomatic negotiations that would culminate in the Treaty of Gorgia a transformative agreement that reshaped Pecario’s future. The Treaty of Gorgia was signed on July 22, 1717, after months of tense negotiation between the representatives of King Leovigildo II and the Iveric leadership, including Admiral Alonso de Valcárcel, a key figure in the Iveric Republic’s expansionist strategy. The treaty was drafted in the city of Puerto San Jorge on the nearby Gorgia Hills, which served as a symbolic meeting place for the two nations. Under the terms of the treaty, Pecario was reorganized as a semi-autonomous corregimiento (administrative district) within the Iveric Republic.

Although Pecario retained its monarchy, the king’s power was significantly curtailed. Under the Treaty of Gorgia, Pecario’s monarchy, represented by King Leovigildo II of the House of Galdona, was preserved as a ceremonial institution. The king’s role was largely symbolic, serving as a figurehead who embodied the continuity of Pecario’s royal traditions and provided a sense of legitimacy to the new order. Leovigildo II was allowed to keep his royal title and palace in Santa Borbones, the historic capital of Pecario. The monarch's responsibilities were limited to ceremonial duties, such as presiding over public festivals, royal weddings, and religious holidays. The king also held the power to bestow honorary titles, though these carried no political weight. Leovigildo II, along with his descendants, remained a symbol of national unity and cultural heritage but was largely removed from governance. The House of Galdona continued to receive royal stipends, funded by the state, to maintain their status in Pecarian society. Leovigildo II was allowed to remain on the throne as a ceremonial figurehead, while day-to-day governance was overseen by Iveric-appointed officials, including a corregidor. This arrangement placated both the Pecarian nobility, who sought to preserve the monarchy, and the First Iveric Republic, which desired to exert control over the region’s resources and trade routes.

Real power was vested in the hands of the corregidor, a governor appointed by the First Iveric Republic to oversee Pecario's administration. The corregidor acted as the chief executive of the state, managing day-to-day governance and ensuring the implementation of policies laid out by Iverica. The first corregidor of Pecario was Governor Andrés Manrrique, a Pecarian diplomat and military strategist. Manrrique played a key role in stabilizing Pecario after the treaty. To further integrate republican principles, a new legislative body called the Junta Popular was established. This body functioned as an advisory council to the corregidor and allowed for some degree of local representation. The Junta was composed of both Pecarian nobles and influential citizens, including mezcla elites and wealthy landowners. The Junta could proposed laws, offered counsel on governance, and addressed grievances from the populace, but ultimate decision-making power rested with the corregidor and his council of Iveric officials.

The treaty also outlined provisions for military assistance, with Iverica stationing advisors to reorganize Pecario’s disordered army. The Royal Guard of Pecario, once fiercely loyal to the Galdona dynasty, was restructured into a more professional force led by Iveric commanders such as Colonel Esteban de Laria, who played a pivotal role in stabilizing the kingdom. In exchange for military support and governance, Iverica was granted extensive trade privileges, securing access to Pecario’s valuable silver mines, timber, and fertile agricultural lands.

Following the Treaty of Gorgia, Pecario experienced a remarkable demographic and economic boom. Iverica, eager to solidify its influence in the region, encouraged large-scale immigration to Pecario. Between 1717 and 1730, thousands of Iveric settlers, primarily from the coastal cities of Porto L'Norte and Súbic migrated to Pecario. These settlers, many of whom were skilled artisans, traders, and farmers, brought with them advanced agricultural techniques, including crop rotation and irrigation systems, which revitalized Pecario’s agricultural sector. New industries sprang up around key cities such as Puerto Dorado, Solmarina and San Luis, which became thriving centers of trade. Pecario’s ports became bustling hubs for Iberic ships, facilitating the export of sugar, coffee, and timber to Aurelia, Europa and beyond.

Independence (1752-1760)

(WIP) In the mid-18th century, a civil War broke out in Iverica, resulting in a significant decline in the central government's authority over its colonies, including Pecario. Taking advantage of this period of instability in Iverica, the Pecarian leaders began to claim their autonomy and seek to free themselves from the Iveric authority.

20th century: political instability and coup d’état