Caerlanni War for Independence

| Caerlanni War for Independence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

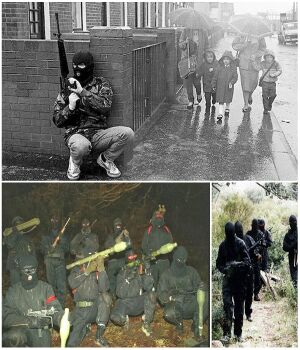

Clockwise from top:

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Supported by: |

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

Military commanders:

|

Military commanders: TBA Political leaders: | ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

c. 80,000 GSC members c. 55,000 other insurgents | Total: TBA | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| TBA | TBA | ||||||||

| TBA | |||||||||

The Caerlanni War for Independence (Caerlanni Mealliagian: Cogadh Neamhspleáchais na gCaerlannaí) was a conflict fought between the Caerlanni Liberation Group (Grúpa Saoirse na gCaerlannaí; GSC) and the Gotneskan Armed Forces from December 12th, 1972, to February 19th, 1976. The war commenced when Ronan Luathach and the GSC launched a coordinated assault on government structures within Dúnradh, the administrative center of Caerlannach under Gotneskan rule. This marked the beginning of an extended confrontation centered in urban areas, where Caerlanni insurgents engaged in prolonged battles against Gotneskan military forces. The conflict concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Fjallaverji, which formally recognized Caerlannach’s independence and established terms for the Gotneskan withdrawal. The Caerlanni War for Independence is widely studied for its unique combination of guerrilla tactics, political mobilization, and its pivotal role in reshaping Caerlannach’s sociopolitical landscape.

Scholars characterize the conflict as an asymmetric and low-intensity war, often framed as a struggle for national liberation. This confrontation encompassed both a tactical insurgency and a profound sociopolitical movement aimed at dismantling Gotneskan hegemony and establishing tribal autonomy across Caerlannach. The GSC drew broad support from various Caerlanni tribes, uniting them around shared objectives of political self-determination and cultural preservation. The war’s ideological foundation was underscored by the GSC’s commitment to indigenous governance, which contrasted sharply with Gotneskan centralized rule.

The origins of the war can be traced to May 1972, when Ronan Luathach returned to Caerlannach from political exile in Fulgistan. Drawing inspiration from contemporary anti-colonial movements, Luathach collaborated with a coalition of local separatist and nationalist factions to form the Caerlanni Liberation Group, including his former Caerlanni Separatist Group. That same year, he authored the "Manifesto of a Free Caerlannach", a document outlining his vision for an autonomous, decentralized society based on tribal governance and cooperation. The manifesto resonated across a broad spectrum of Caerlannach society, galvanizing support for independence and uniting disparate resistance groups under the GSC.

The formal outbreak of hostilities occurred with the Dúnradh Takeover on December 12, 1972, when GSC forces captured key government facilities in the city and announced the formation of the Caerlanni Free State. This decisive action triggered widespread uprisings, with similar revolts erupting in towns and villages across Caerlannach. While early uprisings experienced varying degrees of success, the GSC’s efforts were bolstered by extensive tribal support networks that facilitated intelligence-sharing, logistics, and supplies, complicating Gotneskan attempts to restore control.

The course of the war saw sustained, intense urban conflict, particularly in Caerlanni cities, where maneuver warfare tactics were employed by the tribes. The GSC’s reliance on guerrilla tactics, along with their deep familiarity with Caerlannach’s varied terrain, often enabled them to evade or outmaneuver the Gotneskan military. As the war progressed, the Caerlanni tribes demonstrated resilience through coordinated strategies, establishing supply chains and utilizing the surrounding geography to support their insurgency.

The conflict formally ended in February 1976 after the Gotneskan government, facing domestic fatigue, agreed to negotiate with the GSC leadership. The resulting Treaty of Fjallaverji outlined the terms of Gotneskan withdrawal and included a non-aggression pact between the two parties. The treaty marked the beginning of Caerlannach’s transition from colonial rule to a free state.

Background

The history of Caerlannach’s struggle for autonomy can be traced back to its integration into Gotneska from the 10th century, during which periodic uprisings and expressions of discontent were common. Tensions were exacerbated when the Gotneskan government granted sovereignty to the Kingdom of Crainnruadh, while Caerlannach remained firmly under Gotneskan administration. This decision, made without any parallel concessions to Caerlannach, intensified local resentment. Many Caerlannach saw this as a fundamental disregard for their own aspirations toward self-determination. This perceived disparity galvanized a collective nationalist sentiment, setting the stage for escalated demands for independence.

The Caerlanni Separatist Group (Grúpa Scarúnaí Caerlannaí) emerged as a prominent underground movement advocating for an independent Caerlannach and garnered significant local support. On September 12, 1965, Luathach attempted to assassinate Gotneskan Emperor Patrick XIII, an event that elevated his profile within the separatist circles but resulted in his exile. Although wanted by Gotneskan authorities, Luathach was shielded by the Caerlanni Separatist Group before escaping to Fulgistan, where he continued his activism and writings in exile, all the while maintaining close contact with the movement in Caerlannach.

Despite his absence, Luathach’s influence persisted. His writings, circulated clandestinely within Caerlannach, continued to inspire nationalist and tribal factions advocating for autonomy. These writings underscored themes of self-determination and tribal sovereignty, resonating with movements such as the Ghearóid Free Fighters (Trodairí Saoirse Ghearóid) and the Luathach Independence League (Conradh Neamhspleáchais Luathach), which emerged alongside the Caerlanni Separatist Group to push for liberation. Luathach’s work in exile solidified his role as a symbolic figure for Caerlannach’s independence cause, providing ideological cohesion to a movement that was both diverse and increasingly unified.

On May 29, 1972, Luathach returned to Caerlannach, marking a pivotal moment in the independence struggle. Upon his arrival, he convened the Beinn Rìgh Congress with the Caerlanni Separatist Group, rallying various independence factions to form a coordinated front against Gotneskan rule. This congress culminated in the formation of the GSC, unifying disparate factions under an united front. Soon after, Luathach published the "Manifesto of a Free Caerlannach", a foundational text that articulated the strategic and ideological basis for Caerlannach’s self-determination, laying the groundwork for the forthcoming armed struggle.

Forces

Caerlanni Liberation Group

The GSC were composed predominantly of volunteers from former Caerlanni separatist groups and defectors from the Gotneskan Armed Forces stationed in Caerlannach. Over time, smaller regional and tribal resistance movements unified under the Beinn Rìgh Congress, culminating in the formation of the GSC. While the GSC claimed a total strength exceeding 200,000 fighters, contemporary records suggest that only 40,000–50,000 were actively engaged in combat operations at any given time. The forces were divided into two distinct tactical groups: one, led by General Aodhán Ghearóid, specialized in small-scale urban guerrilla warfare, including sniper campaigns and ambushes; the other, commanded by Séamus Ógalla, utilized large-scale hit-and-run tactics in rural areas, capitalizing on their knowledge of the terrain.

Fulgistan support

During his exile in Fulgistan, Ronan Luathach successfully secured material and financial support from the Fulgistani government. This included arms smuggled through the relatively unsecured Argic Ocean shipping routes. Once delivered to the northern coastline, local tribal networks played a crucial role in transporting these weapons to the GSC militias. The smuggled arsenal included TBA, which became essential for sustaining the protracted guerrilla war against Gotneskan forces.

Gotneskan

TBA

Course of the war

Dúnradh Takeover

The takeover of Dúnradh, the administrative capital of the Protectorate of Caerlannach, marked the beginning of the war. After weeks of meticulous planning, the GSC launched their offensive at dawn on December 12, 1972. The operation was spearheaded by defectors from the Caerlanni Protectorate Army, joined by various militias equipped with smuggled weapons obtained through tribal networks. The offensive concentrated on key governmental buildings, to incapacitate the colonial administration.

While most government officials surrendered without resistance, a small number of loyalist troops entrenched in barracks on the outskirts of the city offered fierce resistance. Intense firefights ensued, resulting in dozens of casualties on both sides.

By 6:30 A.M., Dúnradh was fully under the control of the GSC. Sir Malcolm Armitage, the Lord-Governor of the Protectorate, capitulated after negotiations with Ronan Luathach, the leader of the GSC. Armitage formally surrendered the city and fled to the Goutian Empire, leaving his colonial entourage behind. Shortly afterward, Ronan stood on the balcony of the Dúnradh Governance Hall and proclaimed the formation of the Caerlanni Free State.

Violence spreads

Simultaneously with the Dúnradh takeover, several uprisings broke out across the protectorate. The success of these uprisings varied depending on local conditions. Settlements in the northern and western regions, bolstered by strong militia support, rose to power more effectively than those near the borders with Gotneska. Many northern tribes used their intimate knowledge of the rugged terrain to smuggle weapons and execute guerrilla tactics, successfully overwhelming local colonial garrisons.

In contrast, urban centers closer to Gotneskan supply lines faced brutal suppression. However, these cities became flashpoints for prolonged urban warfare, with militias and civilians alike participating in fierce resistance. The GSC, under the command of General Aodhán Ghearóid, employed a strategic sniping campaign, targeting high-ranking Gotneskan officers to sow chaos and disrupt command structures.

Gotneskan troops, unprepared for the highly decentralized and unconventional tactics of the militias, struggled to adapt. Civilians actively supported the fighters by sabotaging Gotneskan supply lines and providing intelligence to the GSC. This blurred the distinction between combatants and non-combatants, further hampering the effectiveness of the colonial forces.

Aftermath and impact

Truce

By late 1975, the Caerlanni War for Independence had devolved into a stalemate. The GSC and its allied militias controlled significant urban centers across the southern region, while Gotneskan forces retained dominance in the northern territories and along key border regions. Despite this division, skirmishes and minor engagements persisted, creating an atmosphere of continued tension. Emperor Patrick XIII, under increasing pressure from the Lord-Governance of Caerlannach and his cabinet, initiated discussions with the GSC to explore a potential resolution. From the Gotneskan perspective, the prolonged guerilla warfare risked becoming an unending quagmire. For the GSC, the diminishing availability of supplies, the exhaustion of their troops, and the growing risk of tribal dissent made prolonging the conflict untenable.

The impetus for negotiations arose within the Gotneskan leadership, spearheaded by Emperor Patrick XIII, Lord Chancellor [TBA], and General [TBA]. These figures played a pivotal role in persuading the Gotneskan government to seek a negotiated settlement. After considerable internal deliberations, they agreed to engage in formal peace talks with the GSC, aiming to lay the groundwork for the establishment of an independent Caerlanni state.

Negotiations were convened at the neutral location of [TBA] Hall in Fjallaverji. The GSC delegation was led by Diarmaid Uí Caerlann, who would later serve as Foreign Minister during the Deconstructional Period, alongside Commandant Séamus Ógalla, political advisor Aoife Ghearóid, and tribal representative Ciarán Dhomhnaill. The Gotneskan delegation, headed by Lord Chancellor [TBA], included General [TBA] and [TBA]. Despite the ongoing talks, some militias and factions within the GSC viewed the truce as a temporary reprieve and continued sporadic attacks along the northern borders, further complicating the peace process.

Treaty of Fjallaverji

The negotiations ultimately culminated in the signing of the Treaty of Fjallaverji on February 19, 1976. The treaty was ratified by the GSC in the Caerlanni Free State on February 20 and by the Gotneskan government on February 21, formally ending hostilities and marking the establishment of independent Caerlanni state.

The treaty delineated a new border between the Caerlanni Free State and the Goutian Empire, establishing a framework for peaceful coexistence. It further mandated the complete withdrawal of Gotneskan Armed Forces from Caerlannach by May 31, 1976. Additionally, the treaty included provisions for a separate non-aggression pact to be signed at a later date, ensuring long-term stability and preventing the resumption of hostilities.

Wartime damage

According to official figures published in 1978, an estimated 60,000 to 100,000 housing units were destroyed in urban areas. In addition to the housing crisis, approximately 10% of all housing stock was either severely damaged or rendered uninhabitable. Cultural heritage sites suffered significant losses, with 783 structures, including 125 sacral buildings such as churches and temples, destroyed or damaged during the conflict.

The use of landmines during the war posed a lasting danger to the region. Approximately 1 million mines were deployed across Caerlannach, often indiscriminately and without detailed records. A decade after the war, around 150,000 mines remained buried, particularly along the former front lines and portions of the international borders. Efforts to address this hazard extended over decades, and by 2010, all remaining mines were either fully deactivated or clearly marked, significantly reducing the risk to civilians and enabling safer resettlement of affected areas.

Gotneskan Civil War

The costly defeat in the Caerlanni War for Independence had profound repercussions for the Goutian Empire. The financial and human toll of the war, combined with growing domestic fatigue and dissatisfaction, contributed to political instability in Gotneska. The war’s outcome, widely perceived as a national humiliation, was one of the key triggers of the Gotneskan Civil War, which erupted three years later.