Burania

| |

| Demonym | Buran / Buranian |

|---|---|

| Languages | Old Buranic |

| Largest cities | |

The subcontinent of Burania is a region in northeast Europa with colder climates. It stretches from the Kosscow Sea in the west to Karthenia in the east, and from Akiiryu in the south to Deltannia in the north. Depending on different interpretations, some countries in neighbouring areas are sometimes also considered part of the region. Burania in 2020 had a population of about 300 million, most prominently in: Volsci (pop. 146 million) and Akiiryu (75 million).

Etymology

In ancient Buranian mythology, Burr or Buri ("father") is the ancestor of all Buran people. According to an early Aroman account, the nomadic clans who inhabited these lands were ruled by Bur. His story cannot be verified by any other sources, and these strange origins are the subject of much scholarly debate and many disagreements. Burr's name is mentioned only once in an early 5th Century copy of a previous 3rd Century text:

His name, it is written Flavanus

Son of Holy Emperor Venerabilius

Having sailed to Bureas

There has he snatched

much of the maids

of Burr's heir

Along the western regions, the name Burania is also a close match with Bureas or Boreas (Βορέας, also Βορρᾶς), the Aroman god of the cold north wind and the bringer of winter. In this classical iconography, Boreas is frequently described as being really powerful and having a destructive personality. The term is of Proto-Europan origin. In the southern regions, the name was slightly changed to Puran, the highest god of their pantheon and the god of sky, thunder, lightning, storms, and war. Far eastern regions of the subcontinent sometimes use the name Turan or Turania ("The land of Tur"), after their own legendary founder King Tur ("brave") who saved his family from a charging monster, often a dragon.

Geography

Travel to the north of Europa and the sunlight that warms the land begins to dim. The wind that local folktales call the “Breath of Burr” flows from the Argic Ocean in across the land. The north of Burania edges onto the Gulf of Lanjon, with the large Lake Kitezh nearby, a rough border between the steppe Buran and coastal Buran. This land stretches from the boundaries of the islands of the Hexanesa in the west to the Greater Karthenian Range in the east, a march-land between order and chaos that separates the Buran realm from the old Oriental civilisation. At first glance, Burania appears a vast steppe, slowly turning to tundra as one travels north. Only a scattered few highlands mark its surface, a dreary monotonous landscape of paltry hills and fettered frost grass. It is some of the least forgiving country in the world. And while the odd forest can be found within its borders, no crops can grow in northern Burania.

The climate is too frigid through the spring and autumn, with even the warmest days of summer shrouded by grey overcast skies devoid of warmth. Burania is a very inhospitable place, with short warm periods each year and a limited amount of arable land. As Burania was a region where fertile soil was rare and low temperatures made crop failures regular, the people lived in rural areas more infrequently than people from the rest of the continent. In winters, the entire region is transformed by sheets of ice and snow. Swift movement is made impossible. Any unfortunate traveller must stay in place and wait for the weather to break.

The population of interior Burania is overwhelmingly nomadic and consists mainly of clans driven out of the more hospitable lands to the south. Travellers can be found on occasion too, outcasts and exiles on the periphery of their native lands, or Oriental pioneers and Aroman adventurers looking for lost wonders. Only the horsemen are said to inhabit the region year-round, pillaging and raiding across the steppe and tundra before they're forced to make camp for the long winter. The south of the subcontinent extends until the forests of eastern Akiiryu, what they called the “forest people.” Past this southern lies the Eebay and the Amutian desert. And in the west, the Dusart Mountains serve as the natural barrier splitting the Buran steppe from the Akiiryan steppe.

With irregular rainfall in arid summers and long, harsh winters, agriculture has never been extensively practised in Burania, though never totally unknown. Between these barriers lies a territory of vast grassland, rolling hills and low mountains, rivers and lakes. It is a land greatly suited to pastoral nomadism.

Countries

Burania is home to several peoples and countries.

Sometimes also considered part of the Occident:

History

Buran history can be seen as a centuries-long struggle between the nomadic peoples of the plains and the seafaring ones of its coasts. The clans of Buran came from the rugged, inhospitable north known today as Burania. As the Aroman Empire flourished further south, the Buran people live in small settlements, without central government or coinage. In Aroman discourse, the words Buran and Buranic could designate a certain mentality. Buran people were typically depicted as being very strong, with a violent temper to match. Their nomadic lifestyle was contrasted to the urbanised agricultural civilisation of Aroma. The Buran were a civilised people, who flourished on land as well as sea, and the vast majority of them were simple farmers, fishermen, and traders. There exists a founding myth shared by all the peoples of Burania. It tells of three brothers who led their starving and desperate people across the vast lands of the northern subcontinent. At first, the brothers travelled north together, taking refuge beneath the same sky, and speaking with one another in the same tongue. But the longer they travelled, the more spread out they became. First to split off was the eldest brother, who, along with his clan, sought out the beautiful highlands of the West where he saw the wind was blowing freely. The second brother and his clan were next to leave, departing for the vast steppes, fertile beneath the towering peaks of the Greater Karthenian Range in the East. The youngest brother continued north, but found little with which to feed his people. Until one day, as the San began to set, he came sparkling rivers which teemed with fish, feeding into a deep fjord that ended in the Gulf of Lanjon. The identity of the three brothers and what lands they settled have all been wrapped in myth and lost to antiquity.[1] Historically, however, several related yet divergent Buran cultures are distinguished: inland nomadic peoples and the coastal sailors.

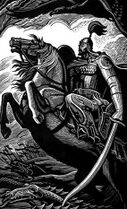

Inland nomads

The Buranian interior has long been home to nomadic steppe cultures living. Buran families lived in felt tents known as yurts. In the great grass seas of the East-Europan plain, the nomads spent their entire lives on horseback, learning to ride before they could walk in order to manage their great herds of sheep, goats, oxen, camels, and the most prestigious, the horse. They domesticated the horse around 3200 BCE, leading to a more mobile lifestyle. A herder was considered to be in poverty if his herd held less than 100 animals, seen as a minimum amount needed for eating and replenishing stock after a hard winter. Overgrazing had to be carefully avoided. In modern central Burania, the expansion of the cashmere industry and resulting growth in goat herds has led to increased desertification of the country.

To successfully do all of this, the Buran gained exceptional experience in logistics, moving their herds without constant loss of life. The herders themselves grew strong, being forced to endure hardship, able to live off of scraps, drinking blood from the veins of their mares or their milk. It was a hard life. This is why the Buran could endure more than regular armies. They were not reliant on baggage trains. In a land of open space, they could quite literally see their enemy coming from many kilometres away.

Each Buran learned to shoot and construct their bows and arrows from a young age, beginning with a child’s bow to hunt marmots and small mammals, gradually increasing the strength of the bow until able to master the powerful, composite recurve war bow. Little boys started out by learning to ride sheep and shoot birds and rats with a bow and arrow. When they grew a little older, they shot foxes and hares, which are used for food. This way, all the young men were able to use the bow and act as armed cavalry in time of war.[2] It's no surprise that the bow was such a favoured weapon. These steppe clans often appear in history as invaders of the Occident and Orient. In the Oriental epic The Scroll of Kings, the name Buran ("land of Bur") appears nearly 450 times. One example is:

No Eurth is visible, no sea, no mountain,

From the many blade-wielders of the Buran horde

While the steppe clans used to live a nomadic life, around 200 CE they settled in the eastern frontier of the Aroman Empire and slowly transitioned into an agrarian society with permanent town centres. However, they still retained many aspects of their nomadic life, including their affinity with horses, as is clearly evident in Akiiryu. A classical education did not exist for them. Instead, children would work hard from an early age and learn to farm, craft, and fight. Hard work was highly respected, and the child most likely to be ostracised or ridiculed would be the one that worked the least. A child would become an adult at the age of 12. Most children stayed at home for several more years after that, however it was not uncommon for boys of that age to be sent on raiding expeditions.

- 900-1400: The 10th century was the start of the Little Ice Age, a disruption in glubal climatic patterns. This resulted in generally cooler and wetter temperatures. These strongly affected the rainy season. In the fourteenth century, this manifested into a general trend of intense colds and snowfall in the polar steppes, irregular droughts in temperate climates, and seemingly unending rainfall in subtropical areas.[3] It had a significant impact on farming harvests. This, in turn, led to increased conflict, human migration, spread of disease. Certainly not a good time to be alive.

- 1050: The Little Ice Age caused the Adlantic Ocean's pack ice to grow.

- 1100s: Climate got colder. Problems with food. Infighting.

- 1200s: Infighting was nearly over. A larger confederation formed. The horselords started raiding the southern lands. They rode in great wagons and chariots, raiding the lands, and destroying or enslaving its people.

- 1250: Alyp Manas (“Brave Lion”) led a major invasion of the Central Europan Steppes. In the east, he defeated the army of Xheng and killed king $PersonName and both his sons at the Battle of $PlaceName. In the south, they allied themselves with local tribes and conquered all the lands around the Skakyan river delta. In the west, he conquered all of the present-day Akiiryu and paused to celebrate.

Coastal sailors

Along the Buran coasts there lived seafaring cultures, of which the Vaarians and Aloorians are the most notable. In peaceful times these Buran sailors spread far from Burania, gaining control of trade routes throughout Europa, building outposts as far as the Orient. As the Aroman Empire expanded north, some Buranians served in their new neighbours' armies and brought home Aroman maritime technology. Competing chieftains quickly refined the new ships to be even more efficient. When not at war, the vessels were used to transport goods and make trade journeys.

In the first centuries of the first millennium, Thelarike and the western coasts of Burania were populated by peoples who sailed the northern seas and traded with the Aromans. One notable leader was Hrothgar of Skjöldung (6th Century CE). When the Aroman Empire collapsed in the 5th century, their privileged trade partners took a heavy economic blow, levelling the playing field a bit for the Buranians. As the region revived, new and vigorous trade routes extended into and through Burania. The wealth that flowed along these routes helped create a new, more prosperous and powerful class of Buranians, whose members competed constantly with each other over trade routes and territory. The Buran, who were renowned travellers, sailed to lands as far as Qubdi and Bashan, and by sailing along the coast of Oriental Europa and the Jasmine Sea, they managed to set up trade missions even as far as Koku, Orioni, and modern Cristina. Thanks to their inventiveness in the face of difficult terrain and weak economies, the Buranians also sailed west, settled the North Adlantic and explored the Argic and Alharun coasts.

Most often, the Buran are typed as seafaring marauders who looted Aroman settlements and recorded their barbaric adventures in epic poetry. But this picture, inspired by the hostile pens of the Aroman clergy, is far from complete. It was only during times of scarcity that they became mercenaries and pirates, frequently attacking ships along the Occidental coast. The zenith of the pirates' power was under the Volscian triumvirate. Most of their attacks were focused on trade lines and unprotected convoys, relying on ambush and surprise. The Buran pirates attacked in large numbers, trying to steal enemy ships using underhanded tactics. Or they disguised themselves as a ship in distress, waiting for their prey to approach.

- 887:

Olrik Naddoddson is banished from Thelarike “because of some killings”. He and his family lead a Buran exploration into the Adlantic Ocean.

Culture

The Buran peoples followed a set of pagan beliefs that would develop into the better-known Old Buran Religion. The religion was polytheistic, with the most important gods being Yksi, especially in places associated with royal power, and Bogd. A great emphasis was put on the worship of ancestral spirits, and rituals comprising sacrifices and offerings were common. Local chieftains took the role of religious leaders when it was necessary. For the Buran, their gods would still exist even if the people wouldn't. And they didn't have to like them, they merely had to deal with them and stay out of their way. The worship of the gods was mostly personal between the individual and the gods, without the presence of a priest, and often the ceremonies partook outside in places of natural beauty. Buran temples were quite rare compared to Aroman churches.

The most important of the Buran holidays was Yule, the celebration of midwinter and the Buran New Year. It marked the point when the San would be at its lowest, and its subsequent rebirth. The first day of Yule was considered the day when the goddess Ingwi would bring love and light back into the wurld. The wild hunt is also starts during Yule, a period of increased supernatural activity when Yksi, riding his eight-legged horse Sleipnir, would roam the wurld together with the dead. The Midsummer holiday marked the height of the San's power, and it was during this time that most foreign trade and raiding were conducted. The Winter Nights' festival marked the beginning of winter. Trade, travel and war would often cease during this period and hunting and feasting would take their place.

The Curse of Buran is a belief that Buran people have been under the influence of a malicious spell for many centuries. The "curse" manifests itself as pessimism, inner strife, and several historic misfortunes. The curse is also blamed for causing many personal troubles. Examples of this curse include the defeat against the Aromans at the Battle of Cryophobae in 279, the loss of Vanarambaion to the Aroman successor states in 699, and more recently the Buranian Spring of 2018 which was crushed by Volscian military and led to severe reprisals and mass exodus of many Europans.

WIP

- History

- Legendary hero Rostam.

- Another potential mythological leader: "Burebista (Ancient Greek: Βυρεβίστας, Βοιρεβίστας) was a Thracian king of the Getae and Dacian clans from 82/61 BCE to 45/44 BCE."

- Described in the Orient by Puranas and Bhagavata Purana.

- Look to these LOTR pages for inspiration:

- Culture

- (Pseudo-Anglo-Germano-Russo-Fennoscandian cultures)

- Upper aristocracy: "A boyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal Bulgarian, Russian, Serbian, Wallachian, Moldavian, and later Romanian and Baltic states aristocracies."

- Scythian clans such as the Roxolani.

- Nationalist movement Turanism

- Separate Turanid race?

- Economy

- Koruna currency: Bohemian and Moravian koruna.

See also

References

- ↑ Republic of Polania | 1920+ // Iron Harvest by The Templin Institute (1 September 2020)

- ↑ Mongol Army: How it All Started by Kings and Generals (18 June 2020)

- ↑ How the Mongols Lost China by Kings and Generals (9 January 2022)