Shakya

Shakyan Principalities Shakeia Mapuriti | |

|---|---|

| from 500s BCE – to 500s CE | |

|

Flag of the Shakyan Principalities (reconstructed) | |

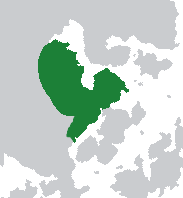

Map of Shakya | |

| Status | Kingdom |

| Capital | Dvaraka |

| Common languages | Shakeysian languages, including Arakaine, Kurdokaine, Nakhaine, and Sokhaine |

| Religion | Juruvanism |

| Government | Theocratic Monarchy |

| Today part of | |

Shakyan Principalities (Shakeia Mapuriti) was a network of approximately eighteen theocratic-monarchical city-states that existed from the 500s BCE to the 500s CE in the Oriental region of eastern Europa on Eurth. Though individualised, these city-states shared a collective identity, often abbreviated to Shakya. Its capital was the city of Dvaraka. The territory is now part of Kotowari, Mahana and Zekistan.

Etymology

The name “Shakya” or “Shakeia” as used in the Shakyan Principalities, is rooted in several linguistic and cultural sources. The most direct etymology comes from the !Sanskrit form “Śākya” and the !Pāli forms “Sakya” and “Sakka.” These names have been linked to the !Sanskrit root śak (शक्) with its variations, śaknoti (शक्नोति), śakyati (शक्यति) or śakyate (शक्यते), denoting ability, worthiness, possibility, or practicability. This root signifies the Shakyan Principalities' self-perception as capable and worthy entities.

Moreover, “Shakya” has also been traced to the !Sanskrit name for the śaka or sāka tree. This name association is believed to be tied to the cultural practice of worshipping these trees, thereby lending a spiritual dimension to the name. The word śākhā (शाखा), meaning 'branch,' is also associated with these trees, symbolising the shared branches of culture and language that united the Shakyan Principalities.

In the broader Eurth context, the name “Shakya” also reflects connections to historical Buran people. Represented in this context by the nomadic groups from Burania, these communities occasionally conducted incursions into neighbouring lands for resources or to overcome internal challenges. The adoption of the name “Shakya” thus might also suggest the Principalities' resilience and adaptability in the face of such pressures, much like the historical Scythians. Therefore, the name Shakyan Principalities encapsulates their self-image of strength and capability, their spiritual customs, their interconnected culture, and their resilience against external threats.

Geography

The Shakyan Principalities spanned across part of the Oriental subcontinent of Europa. The region was characterised by diverse landscapes, including mountains, plains, rivers, and forests, allowing for various lifestyles and cultures to thrive. The territory of the Shakyan Principalities today is incorporated into the modern nations of Kotowari, Mahana and Zekistan.

Spanning across mountains, plains, river systems, forests, and coastal areas, the Shakyan Principalities showcased a rich topographic diversity. The landscape was predominantly divided between the highlands and lowlands. The highlands, featuring rugged mountain ranges, were a natural protective barrier for the Principalities. These mountains were interspersed with fertile valleys, which served as agricultural hubs. In contrast, the lowlands were characterised by expansive plains, which facilitated pastoral activities and cultivation. Here, the major urban settlements, including the capital city of Dvaraka, were predominantly located.

An integral geographical feature was a significant river delta, where one of the region's main rivers fragmented into numerous channels before meeting the Jasmine Sea. The capital city, Dvaraka, was situated in this delta region. The city was built on partially submerged land, enclosed by defensive walls with four primary gates, demonstrating an intricate balance between human engineering and nature. The coastal regions and the river delta, including Dvaraka, experienced a subtropical climate, characterised by hot, wet summers and mild winters. The inland plains and highlands witnessed a temperate climate with moderate rainfall and distinct seasonal variations.

Geographical features of the Shakyan Principalities also shaped their trade and connectivity. Its eastern seaboard along the Jasmine Sea fostered maritime trade with the Orient, stimulating cultural exchange and economic prosperity. Overland, the Principalities maintained connections with nearby Amutia in the west, enhancing land-based trade networks and mutual cultural influence.

History

Early history

The history of the Shakya region delves deep into the annals of time, drawing connections to early hunting-gathering communities and deer-herding tribes that were the initial denizens of this geographical expanse. Their presence can be traced back to the time when they thrived amidst the natural bounties of the region. It is believed that these early inhabitants, faced with environmental or perhaps socio-political changes, initiated migrations in sequential patterns. They journeyed along the southern fringes of the Amutian desert, seeking lands that offered sustenance and stability. Their journey, driven by both survival and aspiration, led them to a river delta that promised both. By the 21st century BCE, the Shakyan people had established their first significant settlements in this delta, making it a cradle of their evolving civilization.

Throughout the following centuries, the Shakya region witnessed the rise of several Mandalas and princely states. These political entities, with their distinct governance structures and socio-economic systems, played crucial roles in shaping the present-day landscape and identity of the Shakya territory. Their influence is still evident in the cultural, architectural, and administrative remnants scattered across the region. Moreover, there has been scholarly speculation regarding the potential links between the Shakyan people and those of Akiiryu. While definitive evidence remains elusive, certain cultural, linguistic, and historical overlaps hint at possible interactions or shared ancestry between these two groups. This potential connection, however speculative, adds another layer of intrigue to the already rich mixture of Shakya's history.

Mandalas

Over time, the region evolved into the Shakyan Principalities, a system of loosely-connected theocratic-monarchical city-states. The Shakyan Principalities consisted of several overlapping dynasties, each governing one of the seven major Principalities or Mandalas.[a] While occasional attempts were made by dominant dynasties to exert control over the others, the principalities quickly regained their independence after such periods of dominance.

Each Mandala or city-centred region of Shakya was associated with a pre-reformed Juruvanic anthropomorphic deity.

- Baviru Puri: Horned Serpent

- Nagura Puri: Abyssal Scorpion

- Khrusos Puri: Jackal

- Dvaraka Puri: Golden Stag

- Aspida Puri: Hedgehog

- Harpia Puri: Eagle

- Kadofari Puri: Skull Frog

- Boska Puri: Ox

- Volucris Puri: Heron

- Pardalea Puri: Lion

- Odonata Puri: Dragon Fly

- Leopara Puri: Leopard

- Chiroptera Puri: Bat

- Tauro Puri: Bull

- Lepus Puri: Hare

- Colibri Puri: Hummingbird

- Pavonina Puri: Peacock

- Canis Puri: Wolf

The last ruler, Sarvikas, presided over a complex system of governance, which was influenced by both internal dynamics and external pressures.

Mardoush's reign

Grand-Prince Azhidahoka “Mardoush” (The Snake-Shouldered) Gaiomardikin marked a significant period in Shakyan history. Mardoush ruled the ancient coastal city of Baviru, by the Jasmine Sea coast. Through military conquest and diplomatic manoeuvrings (!married the Princess of the Scorpion city), he was able to unite the various Shakyan entities for a short period. This included the other six main Principalities or Mapuritis. Legend states that Azhidahoka began as a strong, intelligent, generous and expansionist ruler, however he quickly began experiencing bouts of delusional episodes and fervent paranoia. He allegedly began engaging in ritualistic cannibalism of the priestly and nobility classes in a supposed attempt to live forever.

A blacksmith by the name of Kaova eventually assassinated Grand-Prince Azhidahoka Gaiomardikin which brought about 30 years of political instability, famine, and a series of wars as various principalities vied for power in the vacuum.

Rise of Akhishidinism and subsequent chaos

During the three-decade long chaos, a self-declared prophet by the name of Mazhdika began prophesying a pseudo-atheistic religion based on a form of pacifist altruistic-hedonism, Akhishidinism throughout the principalities. This movement greatly upset the clergy and minor nobility, which began violently oppressing the quickly growing movement. Despite this, Kavodh, a son of Kaova, converted to Akhishidinism and with the support of Mazhdika's followers and (!Foreign mercenaries) was able to end Baviru's chaos and bring a semblance of peace. Prince Kavodh elevated and helped spread Mazhdika's teachings throughout the Northern principalities for a while until his death. While Prince Kavodh laid on his deathbed, his two eldest sons began campaigning for their right to rule Baviru, the presumptive heir Kaovosh and younger brother Khosruo both formed their alliances and eventually prepared for war. During this tenuous moment, Mazhdika would be invited by Khosruo on the pretext to discuss peaceful negotiations and to admire “a new garden with unusually exotic trees”. Soon after Mazhdika's arrival, and upon stepping into the nearby grove, Mazhdika fainted upon seeing 5,000 flayed, impaled, and upside-down men, women and children bodies of Akhishis with their heads covered in the ground. Mazhdika was then tied upside down and is said to have been shot at by a thousand arrows. On the eve of the battle, Kaovosh gave himself in to his brother, citing the love between brothers. Khosruo, on the other hand, now under the influences of the firmly re-established clergy and minor nobility, offered Kaovosh the opportunity to denounce Mazhdika and his teachings, which Kaovosh did not take. Kaovosh was then burned at the stake as a heretic.

Akhishis diaspora

Following these incidents, Khosruo, Prince Kavodh's younger son, mercilessly persecuted the followers of Akhishidinism, known as Akhishis. Many were slaughtered, but a significant number managed to flee the Shakyan Principalities towards Orioni. Today, the Sokhaineans, the numerically dominant ethnicity in Safiloa are partially creolized with strong Azanian and Marenesian influences but are still considered to be linguistically, culturally, religiously, and spiritually the direct descendants of Mazhdika's followers.

Dissolution

The Shakyan Principalities dissolved in the 500s CE, bringing an end to a prosperous yet tumultuous era. Despite the cessation of its existence, its impact continues to have significance in the present-day nations of Kotowari, Mahana, and Zekistan.

Legacy

Despite its dissolution, the Shakyan Principalities left a significant imprint on the culture and history of Kotowari, Mahana and Zekistan. The diverse Shakeysian languages, the unique blend of theocratic-monarchical governance, and the pervasive influence of Juruvanism have left indelible marks on the cultural and societal fabric of these regions. The dramatic historical events have deeply shaped the societal norms and attitudes, while the diaspora of Akhishis has led to the propagation of their faith and cultural influences beyond the boundaries of the Principalities.

Politics

The Shakyan Principalities exhibited a distinctive theocratic-monarchical political system, seamlessly integrating religious and secular governance. In each city-state or Mandala, the ruler, also known as the Mandarajab, was not merely a secular leader but also a religious figurehead. The Mandarajab was considered the earthly representative of the Mandala's associated deity, which was an anthropomorphic figure in pre-reformed Juruvanism. This dual role imbued the Mandarajab's authority with both temporal and spiritual legitimacy, lending the political system a theocratic character. The Mandarajab was responsible for the administration of the Mandala, including the maintenance of law and order, collection of taxes, and overseeing the defence. Simultaneously, they were also responsible for conducting important religious ceremonies and upholding the spiritual well-being of the citizens. The political system was inherently monarchical, with the Mandarajab's position typically hereditary, passing from parent to child. The Mandarajab was often advised by a council of nobles and religious scholars, who provided guidance on administrative and spiritual matters. This council, known as the Sabha, balanced the Mandarajab's authority and offered a measure of political stability.

Each city-state maintained a high degree of autonomy, administering its affairs and upholding its unique traditions and customs. Despite this, the Shakyan Principalities were united by a shared cultural and religious identity, further reinforced by a collective allegiance to the monarch based in the capital city of Dvaraka. The Dvarakan monarch, titled the Parameshvara (Great Lord), held a unique position of prestige and influence. This monarch did not exercise direct control over the other city-states but was recognised as a first among equals, a spiritual guide, and an arbiter in disputes. The Parameshvara's influence, coupled with shared Juruvanic faith and Shakeysian languages, offered the Shakyan Principalities a degree of unity amidst their diversity.

The Shakyan Principalities' unique political system left a lasting legacy in the regions of Kotowari, Mahana, and Zekistan. The blending of secular and religious authority in governance continues to shape political culture, while the principle of autonomous units under a central spiritual leadership is reflected in the federated structures of these modern nations.

Economy

The Shakyan Principalities' economy was diverse and robust, drawing on the region's rich natural resources, agricultural potential, and strategic trade connections. These factors made Shakya a vital economic centre during its existence, and its legacy continues to shape the present local economies.

Shakya was endowed with an abundance of raw materials. Substantial deposits of oil, gas, and coal made it a significant player in the energy sector. These fossil fuel reserves were a vital part of the economy, fuelling both domestic consumption and export revenues. The Shakyan soil was also rich in valuable minerals, including diamonds, gold, silver, and tin. Shakya's diamond mines, in particular, were globally significant, producing over 25% of the diamonds mined in the wurld. The mining sector was a major employer and a critical source of wealth for the Shakyan Principalities.

Agriculture was another pillar of the Shakyan economy. The region's fertile plains and river valleys, coupled with the temperate climate, supported a range of agricultural activities. Crops included grains, fruits, and vegetables, while pastoral farming was also prevalent, particularly in the lowland areas. Agriculture was not just essential for domestic consumption, but also a vital part of the export economy, with Shakyan agricultural produce reaching markets across the Oriental region and beyond.

Given its geographical location, Shakya was a vital hub for trade. Its eastern seaboard along the Jasmine Sea facilitated maritime trade with the Pearl Road network, allowing the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures. Overland, connections with nearby Amutia in the west provided a land-based trade network. Shakya's trading activities were not limited to raw materials and agricultural produce. Its artisans were known for their skill in working with gold, silver, and diamonds, creating exquisite jewellery and decorative items that found markets across Europa, Thalassa, Marenesia, and elsewhere.

Demographics

The population of the Shakyan Principalities was primarily composed of the Shakyan people, who were further divided into subgroups based on their linguistic and regional identities. These subgroups, including the Arakainites, Kurdokainites, Nakhainites, and Sokhainites, each had their unique customs and traditions, adding to the cultural diversity of the region.

Additionally, due to Shakya's strategic location and vibrant trade, several immigrant communities had made the Principalities their home. These included merchants from the Orient, nomadic groups from Burania, and neighbouring Amutians. These communities contributed to the multicultural character of the Principalities, influencing its language, cuisine, and cultural practices.

Society in the Shakyan Principalities was organised in a hierarchical structure. At the top were the rulers, followed by the religious clergy, nobility, artisans, merchants, and labourers. Each city-state in Shakya maintained its social order, governed by local customs, laws, and the principles of Juruvanism.

Religion

Religion, specifically Juruvanism, played a vital role in Shakyan culture. As a theocratic society, Shakya intertwined religious faith with governance and daily life. Juruvanism influenced societal norms, ethical codes, and rituals, shaping the fabric of Shakyan society. Each city-state in Shakya was associated with an anthropomorphic deity from the pre-reformed Juruvanic tradition, which gave each city a unique spiritual character. Religious festivals and rituals were central to Shakyan cultural life, providing occasions for communal celebration and reflection.

The Shakyan culture was marked by its religious faith, Juruvanism, which was integral to the theocratic governance of the city-states. Juruvanism shaped many aspects of daily life and societal norms in Shakya, leaving a lasting influence that can still be seen in the regions of Kotowari, Mahana and Zekistan today.

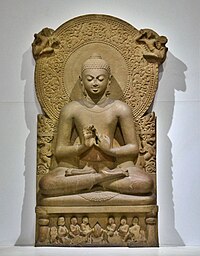

A distinct feature of Shakyan religious life was the presence of sages known as Shakyamuni (Sanskrit: शाक्यमुनि, [ɕaːkjɐmʊnɪ]), meaning "Sage of the Shakyas." The term derives from शाक्य (śākya, “Shakya”) and मुनि (múni, “sage, ascetic”), reflecting their dual identity as both spiritual guides and ascetics. Originally, these figures held a shamanic role, serving as intermediaries between the divine and human realms, performing rituals, interpreting omens, and offering spiritual counsel to rulers and commoners alike. Over time, the Shakyamuni evolved into itinerant prophets who traveled across the Shakyan Principalities, spreading their teachings and guiding communities in matters of faith and morality.

The Shakyamuni were revered for their wisdom and ascetic practices, often living in solitude before embarking on their spiritual journeys. They played a crucial role in shaping theological discourse, challenging established doctrines, and introducing reforms to Juruvanism. Some were regarded as visionaries, while others became advisors to monarchs and spiritual leaders. Their influence extended beyond Shakya, as their teachings spread into neighboring regions, leaving a lasting legacy on religious traditions and philosophical thought.

Languages

Language was a crucial component of Shakyan culture. The Shakeysian languages, including Arakaine, Kurdokaine, Nakhaine, and Sokhaine, were spoken across the Shakyan Principalities. While each of these languages was distinct, they shared common linguistic roots, contributing to a sense of shared cultural identity among the Shakyan people. The Shakeysian languages were not merely tools for communication, but also vessels for cultural expression. Poetry, folk tales, and songs in these languages were integral to Shakyan cultural life, capturing its history, values, and beliefs in evocative forms.

Culture

The culture of the Shakyan Principalities was a rich patchwork woven from threads of language, religion, art, and societal norms. This cultural identity, while diverse, was held together by shared values and traditions, creating a unique societal milieu.

Art and architecture

Art and architecture were distinctive elements of Shakyan culture. Shakyan artisans were renowned for their skill in various crafts, from pottery and textiles to metalwork and jewellery-making. Their creations, often incorporating religious and natural motifs, are valued cultural artefacts that reflect the Shakyan worldview and aesthetics.

Architecture in Shakya blended functionality with spirituality. City layouts and building designs often reflected religious symbolism, while also catering to practical needs. Notable architectural features include the defensive walls and gates of Dvaraka, the elaborate temples dedicated to various deities, and the grand palaces of the rulers.

Aroman representation of Shakyan mounted archer.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ OOC. Inspired by the Chalukya dynasty.