Pecario: Difference between revisions

Mr.Trumpet (talk | contribs) m (→History) |

Mr.Trumpet (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

| common_name = Pecario | | common_name = Pecario | ||

<!-- SYMBOLS --> | <!-- SYMBOLS --> | ||

| image_flag = | | image_flag = Flag of Pecario.png | ||

| alt_flag = <!--alt text for flag (text shown when pointer hovers over flag)--> | | alt_flag = <!--alt text for flag (text shown when pointer hovers over flag)--> | ||

| image_flag2 = <!--e.g. Second-flag of country.svg--> | | image_flag2 = <!--e.g. Second-flag of country.svg--> | ||

| alt_flag2 = <!--alt text for second flag--> | | alt_flag2 = <!--alt text for second flag--> | ||

| image_coat = | | image_coat = Coat of arms Peacario.png | ||

| alt_coat = <!--alt text for coat of arms--> | | alt_coat = <!--alt text for coat of arms--> | ||

| symbol_type = <!--emblem, seal, etc (if not a coat of arms)--> | | symbol_type = <!--emblem, seal, etc (if not a coat of arms)--> | ||

| national_motto = ''"Unidos en la diversidad, juntos hacia el futuro."''<br><small>"United in diversity, together towards the future"</small> | | national_motto = ''"Unidos en la diversidad, juntos hacia el futuro."''<br><small>"United in diversity, together towards the future"</small> | ||

| national_anthem = | | national_anthem = ''[[National Anthem of Pecario|Himno Nacional Pecariano]]<br><small>National anthem of Pecario</small><br>[[File:MediaPlayer.png|link=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eITNZj0kIOA|200px]] | ||

| royal_anthem = <!--in italics (double quotemarks) and wikilinked if link exists--> | | royal_anthem = <!--in italics (double quotemarks) and wikilinked if link exists--> | ||

| other_symbol_type = <!--Use if a further symbol exists, e.g. hymn--> | | other_symbol_type = {{wp|cockade|National cockade}} <!--Use if a further symbol exists, e.g. hymn--> | ||

| other_symbol = | | other_symbol = [[File:National Cockade of Mexico.svg|100px]] | ||

<!-- GEOGRAPHY --> | <!-- GEOGRAPHY --> | ||

| image_map = [[File:Location of Pecario.png|250px]] | | image_map = [[File:Location of Pecario.png|250px]] | ||

| Line 102: | Line 102: | ||

| currency_code = <!--ISO 4217 code/s for currency/ies (each usually three capital letters)--> | | currency_code = <!--ISO 4217 code/s for currency/ies (each usually three capital letters)--> | ||

| time_zone = [[Alharun Central Time]] <!--e.g. GMT, PST, AST, etc, etc (wikilinked if possible)--> | | time_zone = [[Alharun Central Time]] <!--e.g. GMT, PST, AST, etc, etc (wikilinked if possible)--> | ||

| utc_offset = - | | utc_offset = -8 <!--in the form "+N", where N is number of hours offset--> | ||

| time_zone_DST = <!--Link to DST (Daylight Saving Time) used, otherwise "not observed"--> | | time_zone_DST = <!--Link to DST (Daylight Saving Time) used, otherwise "not observed"--> | ||

| utc_offset_DST = <!--in the form "+N", where N is number of hours offset--> | | utc_offset_DST = <!--in the form "+N", where N is number of hours offset--> | ||

| Line 145: | Line 145: | ||

Traces of [[Andalla#Sjådska Period|Sjådska]] presence dating back to 320 BCE on the banks of Manamana Bay attest to an active passage of this people. No physical structure has been discovered, but the discovery of an Útskip wreck near Marelia suggests that the Sjådska used the bay for trading and travel. It is likely that they traded and maintained good relations with the tribes present in the territory. | Traces of [[Andalla#Sjådska Period|Sjådska]] presence dating back to 320 BCE on the banks of Manamana Bay attest to an active passage of this people. No physical structure has been discovered, but the discovery of an Útskip wreck near Marelia suggests that the Sjådska used the bay for trading and travel. It is likely that they traded and maintained good relations with the tribes present in the territory. | ||

The Guaruma civilization was succeeded by the {{wp|Chavín culture|Chávanan culture}}, which thrived from 1,000 to 1,200 AD. The Chávanan people developed more sophisticated systems of irrigation and social stratification, as well as more refined masonry, textiles, and metalworking of {{wp|copper}} and {{wp|gold}}, and the first recognizable artistic style. Following its decline and collapse, the Chávanan culture was succeeded in western Pecario by the {{wp|Moche culture| | The Guaruma civilization was succeeded by the {{wp|Chavín culture|Chávanan culture}}, which thrived from 1,000 to 1,200 AD. The Chávanan people developed more sophisticated systems of irrigation and social stratification, as well as more refined masonry, textiles, and metalworking of {{wp|copper}} and {{wp|gold}}, and the first recognizable artistic style. Following its decline and collapse, the Chávanan culture was succeeded in western Pecario by the {{wp|Moche culture|Lóscos}} and in South-east Pecario by the {{wp|Timoto–Cuica people|Tomóto}}, both of which existed roughly from 100 AD to 800 AD. The Lóscos are famous for their vibrant works of pottery, patterned textiles, and ornate metalworking, while the Tomóto are known for their construction of {{wp|Geoglyphs}} and monumental structures. Unknown troubles, likely related to civil wars according to recent studies, in the 9th century led to the collapse of both cultures and the rise of the {{wp|Muisca|Basáy culture}}, thrived from the 800 AD to the 1100 AD and oversaw a further flourishing of textiles, metalwork, and monumental construction, as well as the development of pottery and large murals. The disappearance of the Basay culture in the 1100s corresponds with the appearance of groups clearly identifiable as the {{wp|Quechua people|Quepec}} and {{wp|Aymara people|Andyo}} peoples. | ||

[[File:Ollantaytambo - Heiliges Tal.jpg|265px|right|thumb|The ruins of | [[File:Ollantaytambo - Heiliges Tal.jpg|265px|right|thumb|The ruins of Kállanka, an important Tuachec town.]] | ||

In the 14th century, the [[Tuachec Empire|Tuachec]], of Quepec origin, emerged as a powerful state which, in the span of a century, will form the largest empire in Mesothalassa with their capital in [[Tualcacán]]. The Tuachec is known to have existed historically by 1250, and, in the subsequent decades, came to control a large area of Northern Pecario. The Tuachecs participated in a confederation with other city-states, initially holding a subordinate rather than dominant position. Under | In the 14th century, the [[Tuachec Empire|Tuachec]], of Quepec origin, emerged as a powerful state which, in the span of a century, will form the largest empire in Mesothalassa with their capital in [[Tualcacán]]. The Tuachec is known to have existed historically by 1250, and, in the subsequent decades, came to control a large area of Northern Pecario. The Tuachecs participated in a confederation with other city-states, initially holding a subordinate rather than dominant position. Under Llóque Hanpaqui, they strengthened their position within the confederation. Thus, upon the death of the last chief of the Confederation, Hupac Yanqui seized control of the confederation, and the Tuachecs imposed their laws on all tribes. This rapid expansion worried several city-states. His successor, Rascar Chalec, was not as successful, and a conspiracy ended his reign. But around 1400, the Tuachecs resumed their expansion under Huayna Cápac. With Huayna Cápac, the Tuachecs solidified its dominance over the region and expands its territory.Gradually, as early as the thirteenth century, they began to expand and incorporate their neighbors. Tuachec leadership sent envoys to cities and towns encouraging them to become members of the empire in exchange for luxury goods and local elites being allowed to retain their titles. Cities which refused to join willingly were conquered and plundered, with local leadership deposed or executed and replaced by loyal nobles. Tuachec expansion was slow until about the middle of the fifteenth century, when the pace of conquest began to accelerate, particularly under the rule of the emperor [[Pómatec]]. Under his rule and that of his son, [[Pómatec Capac II]], the Tuachec came to control the majority of Western Mesothalassa by the 1500s, with a population of 10 to 15 million inhabitants under their rule. Pómatec I also promulgated a comprehensive code of laws to govern his empire, while consolidating his absolute temporal and spiritual authority as the God of the Moon. The official language of the empire was Quepec, although hundreds of local languages and dialects were spoken. The Tuachec leadership encouraged the worship of [[Quilla]], the moon god and imposed its sovereignty above other cults.The Tuachec considered their King, the Vagra Tuachec, to be the "child of the moon". We also owe them the [[Tuachec Empire#Economy|Tuachec Roads]], a vast road network linking the regions of the empire to the capital city. It served as an economic and political integrative axis. | ||

===Conquest and colonial period=== | ===Conquest and colonial period=== | ||

| Line 155: | Line 155: | ||

[[File:Bierstadt Albert The Landing of Columbus.jpg|250px|left|thumb|A depiction of Iberic ''{{wp|Conquistador|conquistadors}}'' landing in Pecario.]] | [[File:Bierstadt Albert The Landing of Columbus.jpg|250px|left|thumb|A depiction of Iberic ''{{wp|Conquistador|conquistadors}}'' landing in Pecario.]] | ||

When [[ | When [[Pómatec IV]], the last Tuachec emperor, became emperor in {{date|1629}}, he inherited an empire weakened by a long famine and divided by quarrels of bellicose nobles. In {{date|October 1630}}, [[Iberic diaspora|Stillian]] conquistador [[Diego de Montega]] landed with his men on the coast of Pecario. He is one of the migrants who was part of the [[Gran Viatge]] fleeing the Iberic Empire. He landed in the Bahía del Fuego Sereno. He quickly established the first Iberic fortified settlement in Mesothalassa named [[Puerto Montega]]. | ||

[[File:Pizarro Seizing the Inca of Peru.jpg|thumb|Montega seizing Pómatec IV.]] | |||

In early 1631, Diego de Montega met with envoys sent by Pómatec IV, who invited him to Tawantinsuyo. Diego de Montega made the trip, accompanied by 1'500 men. In addition to meeting the Tuachec Emperor, Montega met envoys from leaders of rebellious cities that resented Tuachec dominance. Montega agreed to aid them in a rebellion against the Tuachecs. After defeating an important Tuachec forces at [[Battle of Tawantinsuyo|Tawantinsuyo]] where Montega's forces captured Emperor Pomatec IV, the Tuachec emperor became a hostage of Montega and his troops. | |||

During that period, the area of [[Manamana Bay]] was first explored by the Iberic conquistador Sebastián de Salcázaro and his men. In July 1632, the inlet of San Cristobal was first sighted by the Iberics. A landing party went ashore on 25 July 1632, on the day of the feast of San Cristóbal. He completed the conquest of the last places of Tuachec resistance in Manamana aided by Hosco rebels. Despite strong resistance from some generals of Pòmatec IV, including Yuñahi, [[Manamana]] was conquered between 1632 and 1633. Sebastián de Belalcázar founded San Cristobal on 4 April 1633, on the ruins of a Tuachec city, which Yuñahi had destroyed before abandoning it to the Iberics. The Iberics subsequently executed the emperor on 13 June 1633 believing it would make the other Tuachec forces to surrender. Contrary to the predictions of Montega's officers, the death of their emperor encouraged the Tuachec troops to total war, multiplying ambushes and avoiding frontal engagements with the Iberic troops. Following this, the Iberic forces seized and brutally [[Fall of Tualcacán|sacked Tualcacán]] the Tuachec capital on 19 September 1633. The fall of the empire's heart led to the submission of most Tuachec forces. | |||

In 1634, the Kingdom of Pecario was officially proclaimed, with its capital at Santa Borbones and with the conquistadors installing Inti Yupanqui as a puppet emperor on the throne. The conquistadors continued to suppress the remaining Tuachec resistance and the conquest of the former Tuachec Empire's territory. Following this, the Iberics conquered and plundered their former native allies, seeking to ensure their total control over the region. By 1650, the [[Iberic conquest of the Tuachec Empire]] was complete and the Northern part Manamana was under Iberic control. The last Tuachec resistance was suppressed when the Iberican annihilated the Neo-Tuachec State in [[Tuyuq Wasi]] in ({{date|1652}}. | |||

In 1634, the Kingdom of Pecario was officially proclaimed, with its capital at Santa Borbones and with the conquistadors installing Inti Yupanqui as a puppet emperor on the throne. The conquistadors continued to suppress the remaining Tuachec resistance and the conquest of the former Tuachec Empire's territory.Following this, the Iberics conquered and plundered their former native allies, seeking to ensure their total control over the region. By 1650, the [[Iberic conquest of the Tuachec Empire]] was complete and the Northern part Manamana was under Iberic control. The last Tuachec resistance was suppressed when the Iberican annihilated the Neo-Tuachec State in Tuyuq Wasi in 1652. | |||

==== La Gran Peregrinación ==== | ==== La Gran Peregrinación ==== | ||

| Line 173: | Line 169: | ||

Thus, the population of settlers quadrupled within 30 years. By 1700, the Iberic population was estimated at 800,000, and it continued to climb until stabilizing in the mid-20th century. In the 1670s, king [[Francisco Perez]] reorganized the country with gold and silver mining as its main economic activity and native forced labor as its primary workforce. With the discovery of the great silver and gold lodes at San Marañón, the kingdom flourished as an important provider of mineral resources. With the conquest started the spread of Tacolism; most people were forcefully converted to Tacolism, with Iberic clerics believing that the Native Peoples "had been corrupted by the Devil". It only took a generation to convert the population. They built churches in every city and replaced some of the Tuachec temples with churches, such as the Qoli Tempe in the city of Santa Borbones. The church employed the Inquisition, making use of torture to ensure that newly converted Tacolics did not stray to other religions or beliefs, and monastery schools, educating girls, especially of the Tuachec nobility and upper class. Pecarian Tacolism follows the syncretism, in which religious native rituals have been integrated with Tacolic celebrations. In this endeavor, the church came to play an important role in the acculturation of the Natives, drawing them into the cultural orbit of the Iberic settlers. | Thus, the population of settlers quadrupled within 30 years. By 1700, the Iberic population was estimated at 800,000, and it continued to climb until stabilizing in the mid-20th century. In the 1670s, king [[Francisco Perez]] reorganized the country with gold and silver mining as its main economic activity and native forced labor as its primary workforce. With the discovery of the great silver and gold lodes at San Marañón, the kingdom flourished as an important provider of mineral resources. With the conquest started the spread of Tacolism; most people were forcefully converted to Tacolism, with Iberic clerics believing that the Native Peoples "had been corrupted by the Devil". It only took a generation to convert the population. They built churches in every city and replaced some of the Tuachec temples with churches, such as the Qoli Tempe in the city of Santa Borbones. The church employed the Inquisition, making use of torture to ensure that newly converted Tacolics did not stray to other religions or beliefs, and monastery schools, educating girls, especially of the Tuachec nobility and upper class. Pecarian Tacolism follows the syncretism, in which religious native rituals have been integrated with Tacolic celebrations. In this endeavor, the church came to play an important role in the acculturation of the Natives, drawing them into the cultural orbit of the Iberic settlers. | ||

To further encourage settlement, the Iberic authority used native forces as slaves through the {{wp|Encomienda|Encomienda system}}, in which the settlers, were granted indigenous people to use as forced laborers and to educate in the Iberic language and Tacolic religion. This system proved immensely lucrative and the colony quickly became a major producer of cash crops such as {{wp|sugarcane}}, {{wp|coffee}}, and {{wp|Cacao}}. The natives were subjected to severe persecution by the colonizers. They endured numerous unjustified massacres, land and resource dispossession, as well as intense economic exploitation. These combined factors led to a rapid decline in the indigenous population, weakening individuals physically, disrupting their social and economic systems, and introducing destabilizing psychological and cultural pressures. By 1730, the indigenous population was recorded at 5 million compared to approximately 14 million in 1640. The severe abuses associated with the ''Encomienda'' system led to several native rebellions against Iberic in the 17th and 18th centuries, with the most significant - and the last major one - episode being that of Juan Santos Pomatec in 1732, always with the thwarted goal of restoring the territory of the empire. Seeking to further expand Pecario's population, the royal government tacitly permitted intermarriage between white settlers and indigenous women in 1704. A caste system developed in the colony, with ''pies embarrados'' (Europans born in Mesothalassa) at the top, ''pies dorados'' (Europans born in Europa) below them, ''mezcla'' (individuals of mixed race or ethnicity) below them, and indigenous Alharun at the bottom. With the growth of local institutions, the | To further encourage settlement, the Iberic authority used native forces as slaves through the {{wp|Encomienda|Encomienda system}}, in which the settlers, were granted indigenous people to use as forced laborers and to educate in the Iberic language and Tacolic religion. This system proved immensely lucrative and the colony quickly became a major producer of cash crops such as {{wp|sugarcane}}, {{wp|coffee}}, and {{wp|Cacao}}. The natives were subjected to severe persecution by the colonizers. They endured numerous unjustified massacres, land and resource dispossession, as well as intense economic exploitation. These combined factors led to a rapid decline in the indigenous population, weakening individuals physically, disrupting their social and economic systems, and introducing destabilizing psychological and cultural pressures. By 1730, the indigenous population was recorded at 5 million compared to approximately 14 million in 1640. The severe abuses associated with the ''Encomienda'' system led to several native rebellions against Iberic in the 17th and 18th centuries, with the most significant - and the last major one - episode being that of Juan Santos Pomatec in 1732, always with the thwarted goal of restoring the territory of the empire. Seeking to further expand Pecario's population, the royal government tacitly permitted intermarriage between white settlers and indigenous women in 1704. A caste system developed in the colony, with ''pies embarrados'' (Europans born in Mesothalassa) at the top, ''pies dorados'' (Europans born in Europa) below them, ''mezcla'' (individuals of mixed race or ethnicity) below them, and indigenous Alharun at the bottom. With the growth of local institutions, the kingdom's increasingly large ''pies embarrados'' and ''mezcla'' populations began to develop a uniquely Alharun identity. | ||

=== Conquest (1687-1689) === | === Conquest (1687-1689) === | ||

| Line 204: | Line 200: | ||

=== Independence (1752-1760) === | === Independence (1752-1760) === | ||

In the mid-18th century, a [[History of Peninsular Iverica#The Second Republic and the Decades of Civil Strife| civil War]] broke out in [[Iverica]], resulting in a significant decline in the central government's authority over its colonies, including Pecario. Taking advantage of this period of instability in Iverica, the Pecarian leaders began to claim their autonomy and seek to free themselves from the Iveric authority. | |||

In 1752, faced with pressure from independence movements and due to the civil war, the Iveric government decided to withdraw peacefully from its colonies, including Pecario. The [[Treaty of Soledad]] formalized the country's independence. | By the early 1750s, Pecario was teetering on the edge of rebellion. The colony’s elite, led by General [[Andres Torres]] and a cadre of pro-independence intellectuals, began advocating for autonomy. They were opposed by staunch loyalists, primarily made up of landowners and military officers who had long benefitted from Iverica’s protection and economic system. This faction, led by Colonel Francisco Cordero, retreated to the mountainous region of the Cordillera del Sol, determined to resist the separatists through guerrilla warfare. In 1752, faced with pressure from independence movements and due to the civil war, the Iveric government decided to withdraw peacefully from its colonies, including Pecario. The [[Treaty of Soledad]] formalized the country's independence. | ||

However, despite the peaceful withdrawal of the Iverican government, tensions remain between the loyalists and the separatists. The loyalists refused to recognize the treaty, arguing that the political situation in Iverica rendered the signing null and void. The loyalists accused the separatists of traitors to the Republic and took up arms. The first clash took place in [[Santa Borja]] in {{date|February 1753}}. The separatists, led by | However, despite the peaceful withdrawal of the Iverican government officials, tensions remain between the loyalists and the separatists. The loyalists refused to recognize the treaty, arguing that the political situation in Iverica rendered the signing null and void. The loyalists accused the separatists of traitors to the Republic and took up arms. General [[Francisco Cordero]], a high-ranking officer in the Pecarian colonial military, became the de facto leader of the Loyalist forces in Pecario. Cordero was a staunch defender of Iverican rule, having gained significant wealth and influence under the colonial system. He was joined by other influential landowners and officials who shared a vested interest in maintaining Pecario’s ties to Iverica. This faction believed that independence would lead to chaos, economic ruin, and the dismantling of the established social order. The Loyalists were well-organized and strategically retreated to the Cordillera del Sol, a mountainous region in northern Pecario. From these natural fortifications, they conducted a guerrilla war against the separatists, using the terrain to their advantage to stage ambushes and disrupt pro-independence efforts. Their stronghold in the mountains provided them with a degree of resilience, even as separatist forces gained popular support in the lowlands. The first clash took place in [[Santa Borja]] in {{date|February 1753}}. The separatists, led by [[Andres Torres]], won a crucial victory that strengthened their determination. | ||

[[File: | Yet another complication arose from a faction in the southeastern region of Pecario, known as [[Manamana]]. It had always been somewhat distinct from the rest of Pecario, culturally and geographically. Its leaders, closely tied to the Iverican elite, had developed strong economic and military links with the Iveric republic. As the winds of independence swept across Pecario, Manamana’s ruling class, under the leadership of Duke [[Esteban de la Rosa]], took a drastically different path. They vehemently opposed the separatists, and in 1753, while Pecario fought to sever its ties with Iverica, Manamana proclaimed its own independence, not as a free state, but as a loyalist stronghold. While the rest of Pecario sought independence, Manamana aligned itself as a protectorate of Iverica, effectively splitting from Pecario. For decades, this would create a bitter divide between the two regions, a source of national tension that would last well into the 20th century. | ||

[[File:Congreso de Chilpancingo.png|thumb|right|Signature of the second Treaty of Soledad in 1766.]] | |||

Back in the heart of Pecario, another faction emerged, one that sought not just independence from Iverica, but a return to the glory days of the [[Kingdom of Pecario]], which had existed prior to its annexation by Iverica in 1717. This faction, calling themselves the [[''Restauradores'']], believed that Pecario should once again become a monarchy, ruled by a king with absolute power. For them, the Treaty of Soledad was not a victory but a tragedy. They wanted to see Pecario restored to its former size and strength, including the reclamation of Manamana, which had been part of the old kingdom. The ''Restauradores'' were primarily composed of former royalists and members of the old aristocracy, many of whom had lost power and influence when the kingdom fell under Iverican rule. Leading this faction was [[Don Ignacio Valdez]], a prince of Pecario’s ruling dynasty. Don Ignacio believed that Pecario needed back a strong, centralized monarchy to stabilize the fractured nation. He and his followers campaigned for the restoration of the kingdom, with the king given full executive powers, rather than the symbolic role he now played. King Alfonso IV did not officially endorse the ideas of the ''Restauradores''. While many within the royalist movement rumored that the king secretly supported their cause, Alfonso IV maintained a carefully neutral stance in public. The king was known to confide in his closest advisors that while he valued the loyalty of the ''Restauradores'', he did not believe that reinstating the monarchy in its old form was the solution to Pecario’s challenges. He feared that such a move would alienate the republican forces that had fought so hard for independence and could lead to fresh divisions in the already fractured country. The ''Restauradores'' formed a significant opposition force during Pecario’s War of Independence. Although they didn’t take up arms like the loyalists, they lobbied fervently to influence the outcome of the war. They envisioned a Pecario where the royal family would return to power and undo the republican ideals that had taken root among the separatists. They found sympathizers in the wealthy classes of [[Santa Borbones]] and the former royal capital of [[Fortaleza]]. | |||

As the war between the separatists and loyalists raged, Manamana became a flashpoint for conflict. While Pecario fought for freedom, Duke Esteban de la Rosa fortified Manamana’s borders, ensuring that the region would remain a bastion of Iverican influence. In 1756, General Ricardo Morales, a key figure in the separatist movement, attempted to launch an incursion into Manamana, hoping to bring the region back under Pecarian control. However, the campaign ended in disaster. Morales was ambushed and killed near San Cristobal, and the separatists were forced to retreat. The loyalist forces in Manamana, backed by Iverican reinforcements, held their ground, ensuring that the region would remain under Iverican rule for nearly two more centuries. Manamana would continue under Iverican control, only gaining full independence in 1949, when a new wave of decolonization swept the region. | |||

In {{date|August 1760}}, the [[ | The death of Morales was a severe blow to the independence movement, but it did not stop the momentum of the separatists. General Andres Torres, along with [[Diego Ramirez]], a brilliant tactician from Valle Verde, took over leadership of the revolutionary forces. They regrouped and launched a final offensive against the loyalist strongholds. In {{date|August 1760}}, the decisive [[Battle of Valle Verde]] saw the separatists crush the last remnants of loyalist resistance. Colonel Cordero, who had fought tirelessly for the Iverican cause, was captured and executed, marking the end of the loyalist campaign in Pecario. With the loyalists defeated, the [[Treaty of Bochines]] was signed in September 1760, formally ending the Pecarian War of Independence. General Andres Torres was hailed as the liberator of Pecario and was unanimously elected as the first president of the newly-formed Republic of Pecario. In 1766, the [[Treaty of Soledad]] was re-signed in Santa Borbones after Iverica’s own civil war had come to an end. This time, Iverica officially recognized Pecario’s independence, putting an official end to the colonial era. | ||

Tensions continued to simmer beneath the surface, with the ''Restauradores'' still advocating for a return to monarchy, and Manamana remaining an unresolved issue. Manamana’s continued loyalty to Iverica became a point of contention in Pecarian politics. Though the ''Restauradores'' found occasional political influence, particularly during times of instability in the young republic, their dream of a restored kingdom never fully materialized, and Pecario remained a republic. The ''Restauradores'' movement lingered until the mid-19th century, after which it ceased to be significant on the political stage. | |||

Despite Pecario’s independence, Manamana functioned as an autonomous region under Iverican control, creating a bitter divide between the two lands. For nearly two centuries, Pecario’s leaders would grapple with the question of Manamana, but the region’s de facto independence and loyalty to Iverica remained unchallenged until much later. In {{date|February 1768}}, the [[Treaty of San Cristobal]] signed with Manamana would allow for the mutual recognition of the states and the signing of a mutual peace. The most ardent nationalists secretly hoped that this peace would be only temporary and awaited the return of the Manamana region to the state of Pecario. However, their hopes were in vain, and it would not be until the 1930s that a failed attempt to annex Manamana would take place, definitively burying any illusion of reclaiming the region. | |||

===20th century: political instability and coup d’état=== | ===20th century: political instability and coup d’état=== | ||

| Line 304: | Line 306: | ||

| image5 = Desierto Salvador Dalí, Bolivia.jpg | | image5 = Desierto Salvador Dalí, Bolivia.jpg | ||

| caption5 = Guanamo Desert. | | caption5 = Guanamo Desert. | ||

| image6 = | | image6 = Pantanal, south-central South America 5170.jpg | ||

| caption6 = | | caption6 = The Kolnoi, a highly biodiverse wetland. | ||

| image7 = | | image7 = Paisajes de pasto 2.JPG | ||

| caption7 = | | caption7 = Rolling hills typical of the Imaqusina region. | ||

}} | }} | ||

The geography of the country exhibits a great variety of | The geography of the country of Pecario exhibits a great variety of terrains and climates. Pecario has a high level of biodiversity, considered one of the richest in the world, as well as several ecoregions with ecological sub-units. These areas show impressive altitude variations, ranging from 9,500 meters (31,168 feet) at [[Pico del Alba]] to around 70 meters (230 feet) in the coastal plains. | ||

Pecario can be divided into six major geographic regions: | |||

*The '''Cordillera region''' in the North (''Intipallqa'') covers about 34% of the national territory. This region includes some of the highest peaks in Pecario, such as Pico del Alba, with an altitude of 6,900 meters (22,637 feet), and [[Pico Nevado]], at 6,750 meters (22,146 feet). This region is also home to the [[Salar de Luminar]], the largest salt flat in the country, which is an important source of lithium. | |||

* The '''Highlands region''' (''Qollasunka''), located immediately south of the Cordillera, is an intermediate area between the Cordillera mountains and the coastal plains. Dominated by altitudes ranging from 3,500 to 5,500 meters (11,483 to 18,044 feet), this region is a key agricultural and mining center, known for its rich deposits of precious metals. | |||

* The '''Hinterlands region''' (''Antisukara''), located north of the highlands, consists mainly of semi-arid savannas. Although this region is less populated than others, it is particularly well-suited for livestock farming and extensive agriculture due to its climate and geographical conditions. | |||

* The '''Forests region''' (''Chinchamarka'') is the largest geographic region of Pecario. It is dominated by tropical forests that stretch along the country’s southwest coast. This region is mostly flat and sparsely populated, with settlements concentrated near the coast, such as the city of San Luis, the largest in the area. It is home to a great diversity of plant and animal species, although deforestation linked to the timber industry poses threats in certain areas. The vast wetlands of Kolnoi are also located here. | |||

Pecario | * The '''Coastal region''' (''Imaqusina'') stretches along the western and central coasts of the country. This region has been heavily deforested since the 17th century, with only 20% of the original vegetation cover remaining. It is the most densely populated region in the country and hosts the majority of Pecario's industrial and commercial activity. The fertile plains of this region are vital for both subsistence and commercial agriculture. | ||

* The | * The '''Islands region''' (''Mamaqucha'') comprises several small islands off the coast of Pecario. These islands are mostly flat, with fertile soils and beaches, and host wetlands rich in biodiversity. The [[Alacazara|Alcazara Archipelago]] is the most well-known island group in Pecario. The main rivers of Pecario are the [[Río Frontera]] and the [[Río Grande del Sol]] (and its three small tributaries Sayri, Chakayacu, and Allpamayu), all of which flow into Manamana Bay. | ||

[[File:Llamas, Laguna Milluni y Nevado Huayna Potosí (La Paz - Bolivia).jpg|thumb|Llamas and mountains of the Cordillera del Sol in Las Cumbres.]] | [[File:Llamas, Laguna Milluni y Nevado Huayna Potosí (La Paz - Bolivia).jpg|thumb|Llamas and mountains of the Cordillera del Sol in Las Cumbres.]] | ||

| Line 750: | Line 760: | ||

{{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

{{Eurth}} | {{Eurth}} | ||

{{Pecario}} | |||

[[Category:Pecario]] | [[Category:Pecario]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:45, 14 November 2024

Republic of Pecario República de Pecario | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Unidos en la diversidad, juntos hacia el futuro." "United in diversity, together towards the future" | |

| Anthem: Himno Nacional Pecariano National anthem of Pecario | |

| National cockade | |

Location of Pecario | |

Map of Pecario | |

| Capital | Santa Borbones |

| Largest | Valleluz |

| Official languages | Iverican, Stillian |

| Recognised national languages | Iverican, Stillian Iverican, Stillian, Quepec, Guaruma, other indigenous languages |

| Demonym(s) | Pecariano, Pecarian |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

• President | Andreas Lineria |

• Vice President | Gabriel Valdez |

• President of the Senate | Carlos Rojas |

| Legislature | Congress |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Representatives | |

| Independence | |

• Declared | 1752 |

• Recognized | 1766 |

| Area | |

• | 324,700 km2 (125,400 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | 22,658,480 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | $200 billion |

• Per capita | $9,995 |

| Gini | 0.38 low |

| HDI | 0.800 very high |

| Currency | Pecarian pesos |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Alharun Central Time) |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy BCE/CE |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +39 |

| Internet TLD | .pco |

Pecario, officially known as known officially in Iverican as La República de Pecario, concisely as the Republic of Pecario, and informally as Pecario, is a sovereign state in Alharu on Eurth. It is bordered on the South by Manamana. The seat of government is Santa Borbones, which contains the executive, legislative, and electoral branches of government,it is also the constitutional capital and the seat of the judiciary. The largest city and principal industrial center is Valleluz.

The sovereign state of Pecario is a constitutionally unitary state, divided into nine departments. Its geography varies from the peaks of the Cordillera del Sol in the North, to the eastern lowlands. A third of the country is in the mountain range. The country's population, estimated at 22 million, is multi-ethnic, including natives, mestizos and europans (mainly Ivericans). Iverican is the official and predominant language, although 36 indigenous languages also have official status, the most commonly spoken of which are quepec, aymaro and guaruma.

The history of Pecario begins with the dominance of the Tuachec Empire in the 15th century, followed by the Iverican conquest in the 17th century. After uprisings, the country gained independence in 1753. The 19th century was marked by political instability, but also by progress in education and civil rights. In the 20th century, periods of military control alternated with democratic governments, seeking to combat corruption and inflation. In 2002, an unprecedented economic crisis struck, leading to the resignation of President Eduardo Chapo. Luis Mesa came to power in 2006, ushering in a calmer period until 2019. The Santa Polvo Cartel emerged in 2010, taking control of the drug trade leading to a drug war. President Mesa will resign in 2019 after a scandal related to the Santa Polvo cartel, he will be replaced by Andreas Lineria. Today the country is one of the most corrupt state in the wurld, the government of Presidente Lineria is completely under the orders of the cartel and pretends not seeing the recurring massacres in the country. In 2020, the country was classified as a Narco-State due to the Pecarian government turning a blind eye towards drug cartels. Today, Pecario is plagued by corruption and violence related to drug trafficking.

Etymology

According to legend, centuries ago, before the formation of the country we know today as Pecario, the lands were inhabited by indigenous tribes. Among these tribes, there was a particularly respected and influential group that worshipped a sacred animal: the "Pecario".

The Pecario is an emblematic animal of the region, a rare and mysterious creature, similar to a wild boar but with distinctive features. Its presence is considered a sign of fertility and prosperity for indigenous communities. The ancients considered the pecario as the guardian of forests, rivers and mountains, and they attached great spiritual importance to him. When the Iberic conquerors arrived in the area, they were intrigued by the stories of this sacred animal. They began naming the area after this legendary being, "Pecario," in homage to its deep cultural significance and importance to indigenous peoples.

Thus, the name "Pecario" became the symbol of the connection between the past and the present, a reminder of the cultural roots of this fictitious nation, rooted in respect for nature and the harmonious coexistence between man and the earth.

History

Prehistory and Tuachec period

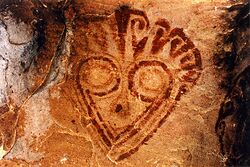

Human presence in Pecario can be dated as far back as 12,000 BCE, with human remains and stone tools in the Vallejo valley providing some of the earliest discovered evidence of human habitation in Mesothalassa. The domestication of the potato occurred in Mesothalassa some time between 8,000 BCE and 5,000 BCE; the cultivation of corn spread to the region between 5,000 and 4,000 BCE, and the domestication of quinoa occurred in roughly 2,000 BCE. Indigenous Pecarians also domesticated the llama, alpaca, and guinea pig in Pecario in roughly 6,000 BCE. They carved into rocks many petroglyphs throughout the country, notably those located in San Cristóbal.

The first civilization, Guaruma civilization which had its capital at Guaruma, emerged in the east of Pecario. The capital city of Guaruma dates from as early as 1,500 BCE when it was a small village based on agriculture. The Guaruma community grew to urban proportions between 700 BCE and 900 BCE, becoming an important regional power in Mesothalassa. Guaruma sites are marked by the presence of central pyramids and monoliths, irrigation systems, and terraced farms. As the rainfall decreased, the surplus of food decreased, and thus the amount available to underpin the power of the elites. The Guaruma civilization disappeared around 900 AD.

Traces of Sjådska presence dating back to 320 BCE on the banks of Manamana Bay attest to an active passage of this people. No physical structure has been discovered, but the discovery of an Útskip wreck near Marelia suggests that the Sjådska used the bay for trading and travel. It is likely that they traded and maintained good relations with the tribes present in the territory.

The Guaruma civilization was succeeded by the Chávanan culture, which thrived from 1,000 to 1,200 AD. The Chávanan people developed more sophisticated systems of irrigation and social stratification, as well as more refined masonry, textiles, and metalworking of copper and gold, and the first recognizable artistic style. Following its decline and collapse, the Chávanan culture was succeeded in western Pecario by the Lóscos and in South-east Pecario by the Tomóto, both of which existed roughly from 100 AD to 800 AD. The Lóscos are famous for their vibrant works of pottery, patterned textiles, and ornate metalworking, while the Tomóto are known for their construction of Geoglyphs and monumental structures. Unknown troubles, likely related to civil wars according to recent studies, in the 9th century led to the collapse of both cultures and the rise of the Basáy culture, thrived from the 800 AD to the 1100 AD and oversaw a further flourishing of textiles, metalwork, and monumental construction, as well as the development of pottery and large murals. The disappearance of the Basay culture in the 1100s corresponds with the appearance of groups clearly identifiable as the Quepec and Andyo peoples.

In the 14th century, the Tuachec, of Quepec origin, emerged as a powerful state which, in the span of a century, will form the largest empire in Mesothalassa with their capital in Tualcacán. The Tuachec is known to have existed historically by 1250, and, in the subsequent decades, came to control a large area of Northern Pecario. The Tuachecs participated in a confederation with other city-states, initially holding a subordinate rather than dominant position. Under Llóque Hanpaqui, they strengthened their position within the confederation. Thus, upon the death of the last chief of the Confederation, Hupac Yanqui seized control of the confederation, and the Tuachecs imposed their laws on all tribes. This rapid expansion worried several city-states. His successor, Rascar Chalec, was not as successful, and a conspiracy ended his reign. But around 1400, the Tuachecs resumed their expansion under Huayna Cápac. With Huayna Cápac, the Tuachecs solidified its dominance over the region and expands its territory.Gradually, as early as the thirteenth century, they began to expand and incorporate their neighbors. Tuachec leadership sent envoys to cities and towns encouraging them to become members of the empire in exchange for luxury goods and local elites being allowed to retain their titles. Cities which refused to join willingly were conquered and plundered, with local leadership deposed or executed and replaced by loyal nobles. Tuachec expansion was slow until about the middle of the fifteenth century, when the pace of conquest began to accelerate, particularly under the rule of the emperor Pómatec. Under his rule and that of his son, Pómatec Capac II, the Tuachec came to control the majority of Western Mesothalassa by the 1500s, with a population of 10 to 15 million inhabitants under their rule. Pómatec I also promulgated a comprehensive code of laws to govern his empire, while consolidating his absolute temporal and spiritual authority as the God of the Moon. The official language of the empire was Quepec, although hundreds of local languages and dialects were spoken. The Tuachec leadership encouraged the worship of Quilla, the moon god and imposed its sovereignty above other cults.The Tuachec considered their King, the Vagra Tuachec, to be the "child of the moon". We also owe them the Tuachec Roads, a vast road network linking the regions of the empire to the capital city. It served as an economic and political integrative axis.

Conquest and colonial period

When Pómatec IV, the last Tuachec emperor, became emperor in 1629, he inherited an empire weakened by a long famine and divided by quarrels of bellicose nobles. In October 1630, Stillian conquistador Diego de Montega landed with his men on the coast of Pecario. He is one of the migrants who was part of the Gran Viatge fleeing the Iberic Empire. He landed in the Bahía del Fuego Sereno. He quickly established the first Iberic fortified settlement in Mesothalassa named Puerto Montega.

In early 1631, Diego de Montega met with envoys sent by Pómatec IV, who invited him to Tawantinsuyo. Diego de Montega made the trip, accompanied by 1'500 men. In addition to meeting the Tuachec Emperor, Montega met envoys from leaders of rebellious cities that resented Tuachec dominance. Montega agreed to aid them in a rebellion against the Tuachecs. After defeating an important Tuachec forces at Tawantinsuyo where Montega's forces captured Emperor Pomatec IV, the Tuachec emperor became a hostage of Montega and his troops.

During that period, the area of Manamana Bay was first explored by the Iberic conquistador Sebastián de Salcázaro and his men. In July 1632, the inlet of San Cristobal was first sighted by the Iberics. A landing party went ashore on 25 July 1632, on the day of the feast of San Cristóbal. He completed the conquest of the last places of Tuachec resistance in Manamana aided by Hosco rebels. Despite strong resistance from some generals of Pòmatec IV, including Yuñahi, Manamana was conquered between 1632 and 1633. Sebastián de Belalcázar founded San Cristobal on 4 April 1633, on the ruins of a Tuachec city, which Yuñahi had destroyed before abandoning it to the Iberics. The Iberics subsequently executed the emperor on 13 June 1633 believing it would make the other Tuachec forces to surrender. Contrary to the predictions of Montega's officers, the death of their emperor encouraged the Tuachec troops to total war, multiplying ambushes and avoiding frontal engagements with the Iberic troops. Following this, the Iberic forces seized and brutally sacked Tualcacán the Tuachec capital on 19 September 1633. The fall of the empire's heart led to the submission of most Tuachec forces.

In 1634, the Kingdom of Pecario was officially proclaimed, with its capital at Santa Borbones and with the conquistadors installing Inti Yupanqui as a puppet emperor on the throne. The conquistadors continued to suppress the remaining Tuachec resistance and the conquest of the former Tuachec Empire's territory. Following this, the Iberics conquered and plundered their former native allies, seeking to ensure their total control over the region. By 1650, the Iberic conquest of the Tuachec Empire was complete and the Northern part Manamana was under Iberic control. The last Tuachec resistance was suppressed when the Iberican annihilated the Neo-Tuachec State in Tuyuq Wasi in (1652.

La Gran Peregrinación

The fall of the Tuachec Empire led to a significant political upheaval that reverberated beyond borders and into Alharu. Some settlers extolled, through texts and letters addressed to the Iberic Empire, describing news that the colony was rich in gold and silver. It triggered a flood of fortune-seekers, who increased the newfly kingdom's population and expanded its frontiers. This resulted in several waves of migration to the kingdom of Pecario, particularly in the years 1645 and 1650, where the influx of settlers was so significant that some cities had to turn people away. As the mayor of Valleluz, Pedro Alcazar de Guantaneo, wrote in 1647: "Thus, we saw a moving tide arriving, pressing at the gates of the city. The soldiers struggled to contain them. Women, children, and men eagerly awaited the opportunity to settle and cultivate the vast surrounding lands. There was, of course, a sense of disdain from the "old" settlers towards the newcomers. A man remains a man even in the face of his peers."

Thus, the population of settlers quadrupled within 30 years. By 1700, the Iberic population was estimated at 800,000, and it continued to climb until stabilizing in the mid-20th century. In the 1670s, king Francisco Perez reorganized the country with gold and silver mining as its main economic activity and native forced labor as its primary workforce. With the discovery of the great silver and gold lodes at San Marañón, the kingdom flourished as an important provider of mineral resources. With the conquest started the spread of Tacolism; most people were forcefully converted to Tacolism, with Iberic clerics believing that the Native Peoples "had been corrupted by the Devil". It only took a generation to convert the population. They built churches in every city and replaced some of the Tuachec temples with churches, such as the Qoli Tempe in the city of Santa Borbones. The church employed the Inquisition, making use of torture to ensure that newly converted Tacolics did not stray to other religions or beliefs, and monastery schools, educating girls, especially of the Tuachec nobility and upper class. Pecarian Tacolism follows the syncretism, in which religious native rituals have been integrated with Tacolic celebrations. In this endeavor, the church came to play an important role in the acculturation of the Natives, drawing them into the cultural orbit of the Iberic settlers.

To further encourage settlement, the Iberic authority used native forces as slaves through the Encomienda system, in which the settlers, were granted indigenous people to use as forced laborers and to educate in the Iberic language and Tacolic religion. This system proved immensely lucrative and the colony quickly became a major producer of cash crops such as sugarcane, coffee, and Cacao. The natives were subjected to severe persecution by the colonizers. They endured numerous unjustified massacres, land and resource dispossession, as well as intense economic exploitation. These combined factors led to a rapid decline in the indigenous population, weakening individuals physically, disrupting their social and economic systems, and introducing destabilizing psychological and cultural pressures. By 1730, the indigenous population was recorded at 5 million compared to approximately 14 million in 1640. The severe abuses associated with the Encomienda system led to several native rebellions against Iberic in the 17th and 18th centuries, with the most significant - and the last major one - episode being that of Juan Santos Pomatec in 1732, always with the thwarted goal of restoring the territory of the empire. Seeking to further expand Pecario's population, the royal government tacitly permitted intermarriage between white settlers and indigenous women in 1704. A caste system developed in the colony, with pies embarrados (Europans born in Mesothalassa) at the top, pies dorados (Europans born in Europa) below them, mezcla (individuals of mixed race or ethnicity) below them, and indigenous Alharun at the bottom. With the growth of local institutions, the kingdom's increasingly large pies embarrados and mezcla populations began to develop a uniquely Alharun identity.

Conquest (1687-1689)

The Kingdom of Lysia, drawn by the riches that the Iberics had discovered, sent colonists to Mesothalassa. This expedition led to the establishment of the colony of Côte d'Émeraude in 1633 to the West of the newly founded Kingdom of Pecario.

By 1680, Pecario had experienced exponential growth and undergone a significant demographic boom due to La Gran Peregrinación. The kingdom then began to seek expansion of its borders and looked eastward. Brief diplomatic exchanges were made between the Lysian governor and Pecarian diplomats, but nothing was officially signed, with the burning question of borders left unanswered. In 1686, King Gilete de Orozco of Pecario, frustrated by the situation, issued an ultimatum to the colony: the Lysians must unconditionally cede a large valuable parts of their colony to the kingdom in order to hope for signing a non-aggression pact and normalizing relations between the two states. The Pecario general staff knew perfectly well that the request would be denied and were actually only looking for a pretext to start a conflict with the colony. Lysian colonial governor Charles de la Roncière formally refused, and thus the Kingdom of Pecario officialy declared war on the colony in March 1687.

The first real battles began in April 1687. Pecario’s numerical and military superiority greatly disadvantaged the colony of Côte d'Émeraude. Colonial diplomats desperately tried several times to request reinforcements from the mainland in Europa, but the Lysian aristocracy gradually lost interest in the matter and preferred to leave the colonists to their fate. A military expedition was deemed too costly and unprofitable. Despite a few vain heroic Lysian victories, the colony’s capital, Saint-Louis, fell into the hands of Pecarian troops in November 1687. The Lysian colonial administration officially surrendered in November 1688. The rest of the territory was fully occupied afterward, although pockets of Lysian resistance persisted until December 1688.

The Treaty of Saint-Louis was signed thereafter, named after the location where it was drafted, and effectively resulted in the annexation of the entire colony of Côte d'Émeraude into the Kingdom of Pecario. Colonists were given the choice to either remain on their lands or leave the territory to try to reach the nearest Lysian colony, Florentia. Most chose to leave the colony, but a minority opted to stay. They formed a community of Lysians centered around Saint-Louis (renamed San Luis after the conflict). The Lysian community of San Luis deeply influenced the city's style and culture. This community still exists to this day.

Iveric corregimiento (1717-1752)

In 1717, the Kingdom of Pecario, faced a critical juncture in its history. Years of internal chaos, including royal succession disputes and civil strife, had weakened the kingdom to the brink of collapse. The powerful noble families, such as the House of Galdona and the House of Virelia, clashed over the throne, leading to widespread instability. Faced with the threat of disintegration, King Leovigildo II, the reigning monarch, and his court turned to the nearby Iveric Republic for help. This marked the beginning of diplomatic negotiations that would culminate in the Treaty of Gorgia a transformative agreement that reshaped Pecario’s future. The Treaty of Gorgia was signed on July 22, 1717, after months of tense negotiation between the representatives of King Leovigildo II and the Iveric leadership, including Admiral Alonso de Valcárcel, a key figure in the Iveric Republic’s expansionist strategy. The treaty was drafted in the city of Puerto San Jorge on the nearby Gorgia Hills, which served as a symbolic meeting place for the two nations. Under the terms of the treaty, Pecario was reorganized as a semi-autonomous corregimiento (administrative district) within the Iveric Republic.

Although Pecario retained its monarchy, the king’s power was significantly curtailed. Under the Treaty of Gorgia, Pecario’s monarchy, represented by King Leovigildo II of the House of Galdona, was preserved as a ceremonial institution. The king’s role was largely symbolic, serving as a figurehead who embodied the continuity of Pecario’s royal traditions and provided a sense of legitimacy to the new order. Leovigildo II was allowed to keep his royal title and palace in Santa Borbones, the historic capital of Pecario. The monarch's responsibilities were limited to ceremonial duties, such as presiding over public festivals, royal weddings, and religious holidays. The king also held the power to bestow honorary titles, though these carried no political weight. Leovigildo II, along with his descendants, remained a symbol of national unity and cultural heritage but was largely removed from governance. The House of Galdona continued to receive royal stipends, funded by the state, to maintain their status in Pecarian society. Leovigildo II was allowed to remain on the throne as a ceremonial figurehead, while day-to-day governance was overseen by Iveric-appointed officials, including a corregidor. This arrangement placated both the Pecarian nobility, who sought to preserve the monarchy, and the First Iveric Republic, which desired to exert control over the region’s resources and trade routes.

Real power was vested in the hands of the corregidor, a governor appointed by the First Iveric Republic to oversee Pecario's administration. The corregidor acted as the chief executive of the state, managing day-to-day governance and ensuring the implementation of policies laid out by Iverica. The first corregidor of Pecario was Governor Andrés Manrrique, a Pecarian diplomat and military strategist. Manrrique played a key role in stabilizing Pecario after the treaty. To further integrate republican principles, a new legislative body called the Junta Popular was established. This body functioned as an advisory council to the corregidor and allowed for some degree of local representation. The Junta was composed of both Pecarian nobles and influential citizens, including mezcla elites and wealthy landowners. The Junta could proposed laws, offered counsel on governance, and addressed grievances from the populace, but ultimate decision-making power rested with the corregidor and his council of Iveric officials.

The treaty also outlined provisions for military assistance, with Iverica stationing advisors to reorganize Pecario’s disordered army. The Royal Guard of Pecario, once fiercely loyal to the Galdona dynasty, was restructured into a more professional force led by Iveric commanders such as Colonel Esteban de Laria, who played a pivotal role in stabilizing the kingdom. In exchange for military support and governance, Iverica was granted extensive trade privileges, securing access to Pecario’s valuable silver mines, timber, and fertile agricultural lands.

Following the Treaty of Gorgia, Pecario experienced a remarkable demographic and economic boom. Iverica, eager to solidify its influence in the region, encouraged large-scale immigration to Pecario. Between 1717 and 1730, thousands of Iveric settlers, primarily from the coastal cities of Porto L'Norte and Súbic migrated to Pecario. These settlers, many of whom were skilled artisans, traders, and farmers, brought with them advanced agricultural techniques, including crop rotation and irrigation systems, which revitalized Pecario’s agricultural sector. New industries sprang up around key cities such as Puerto Dorado, Solmarina and San Luis, which became thriving centers of trade. Pecario’s ports became bustling hubs for Iberic ships, facilitating the export of sugar, coffee, and timber to Aurelia, Europa and beyond.

Independence (1752-1760)

In the mid-18th century, a civil War broke out in Iverica, resulting in a significant decline in the central government's authority over its colonies, including Pecario. Taking advantage of this period of instability in Iverica, the Pecarian leaders began to claim their autonomy and seek to free themselves from the Iveric authority.

By the early 1750s, Pecario was teetering on the edge of rebellion. The colony’s elite, led by General Andres Torres and a cadre of pro-independence intellectuals, began advocating for autonomy. They were opposed by staunch loyalists, primarily made up of landowners and military officers who had long benefitted from Iverica’s protection and economic system. This faction, led by Colonel Francisco Cordero, retreated to the mountainous region of the Cordillera del Sol, determined to resist the separatists through guerrilla warfare. In 1752, faced with pressure from independence movements and due to the civil war, the Iveric government decided to withdraw peacefully from its colonies, including Pecario. The Treaty of Soledad formalized the country's independence.

However, despite the peaceful withdrawal of the Iverican government officials, tensions remain between the loyalists and the separatists. The loyalists refused to recognize the treaty, arguing that the political situation in Iverica rendered the signing null and void. The loyalists accused the separatists of traitors to the Republic and took up arms. General Francisco Cordero, a high-ranking officer in the Pecarian colonial military, became the de facto leader of the Loyalist forces in Pecario. Cordero was a staunch defender of Iverican rule, having gained significant wealth and influence under the colonial system. He was joined by other influential landowners and officials who shared a vested interest in maintaining Pecario’s ties to Iverica. This faction believed that independence would lead to chaos, economic ruin, and the dismantling of the established social order. The Loyalists were well-organized and strategically retreated to the Cordillera del Sol, a mountainous region in northern Pecario. From these natural fortifications, they conducted a guerrilla war against the separatists, using the terrain to their advantage to stage ambushes and disrupt pro-independence efforts. Their stronghold in the mountains provided them with a degree of resilience, even as separatist forces gained popular support in the lowlands. The first clash took place in Santa Borja in February 1753. The separatists, led by Andres Torres, won a crucial victory that strengthened their determination.

Yet another complication arose from a faction in the southeastern region of Pecario, known as Manamana. It had always been somewhat distinct from the rest of Pecario, culturally and geographically. Its leaders, closely tied to the Iverican elite, had developed strong economic and military links with the Iveric republic. As the winds of independence swept across Pecario, Manamana’s ruling class, under the leadership of Duke Esteban de la Rosa, took a drastically different path. They vehemently opposed the separatists, and in 1753, while Pecario fought to sever its ties with Iverica, Manamana proclaimed its own independence, not as a free state, but as a loyalist stronghold. While the rest of Pecario sought independence, Manamana aligned itself as a protectorate of Iverica, effectively splitting from Pecario. For decades, this would create a bitter divide between the two regions, a source of national tension that would last well into the 20th century.

Back in the heart of Pecario, another faction emerged, one that sought not just independence from Iverica, but a return to the glory days of the Kingdom of Pecario, which had existed prior to its annexation by Iverica in 1717. This faction, calling themselves the ''Restauradores'', believed that Pecario should once again become a monarchy, ruled by a king with absolute power. For them, the Treaty of Soledad was not a victory but a tragedy. They wanted to see Pecario restored to its former size and strength, including the reclamation of Manamana, which had been part of the old kingdom. The Restauradores were primarily composed of former royalists and members of the old aristocracy, many of whom had lost power and influence when the kingdom fell under Iverican rule. Leading this faction was Don Ignacio Valdez, a prince of Pecario’s ruling dynasty. Don Ignacio believed that Pecario needed back a strong, centralized monarchy to stabilize the fractured nation. He and his followers campaigned for the restoration of the kingdom, with the king given full executive powers, rather than the symbolic role he now played. King Alfonso IV did not officially endorse the ideas of the Restauradores. While many within the royalist movement rumored that the king secretly supported their cause, Alfonso IV maintained a carefully neutral stance in public. The king was known to confide in his closest advisors that while he valued the loyalty of the Restauradores, he did not believe that reinstating the monarchy in its old form was the solution to Pecario’s challenges. He feared that such a move would alienate the republican forces that had fought so hard for independence and could lead to fresh divisions in the already fractured country. The Restauradores formed a significant opposition force during Pecario’s War of Independence. Although they didn’t take up arms like the loyalists, they lobbied fervently to influence the outcome of the war. They envisioned a Pecario where the royal family would return to power and undo the republican ideals that had taken root among the separatists. They found sympathizers in the wealthy classes of Santa Borbones and the former royal capital of Fortaleza.

As the war between the separatists and loyalists raged, Manamana became a flashpoint for conflict. While Pecario fought for freedom, Duke Esteban de la Rosa fortified Manamana’s borders, ensuring that the region would remain a bastion of Iverican influence. In 1756, General Ricardo Morales, a key figure in the separatist movement, attempted to launch an incursion into Manamana, hoping to bring the region back under Pecarian control. However, the campaign ended in disaster. Morales was ambushed and killed near San Cristobal, and the separatists were forced to retreat. The loyalist forces in Manamana, backed by Iverican reinforcements, held their ground, ensuring that the region would remain under Iverican rule for nearly two more centuries. Manamana would continue under Iverican control, only gaining full independence in 1949, when a new wave of decolonization swept the region.

The death of Morales was a severe blow to the independence movement, but it did not stop the momentum of the separatists. General Andres Torres, along with Diego Ramirez, a brilliant tactician from Valle Verde, took over leadership of the revolutionary forces. They regrouped and launched a final offensive against the loyalist strongholds. In August 1760, the decisive Battle of Valle Verde saw the separatists crush the last remnants of loyalist resistance. Colonel Cordero, who had fought tirelessly for the Iverican cause, was captured and executed, marking the end of the loyalist campaign in Pecario. With the loyalists defeated, the Treaty of Bochines was signed in September 1760, formally ending the Pecarian War of Independence. General Andres Torres was hailed as the liberator of Pecario and was unanimously elected as the first president of the newly-formed Republic of Pecario. In 1766, the Treaty of Soledad was re-signed in Santa Borbones after Iverica’s own civil war had come to an end. This time, Iverica officially recognized Pecario’s independence, putting an official end to the colonial era.

Tensions continued to simmer beneath the surface, with the Restauradores still advocating for a return to monarchy, and Manamana remaining an unresolved issue. Manamana’s continued loyalty to Iverica became a point of contention in Pecarian politics. Though the Restauradores found occasional political influence, particularly during times of instability in the young republic, their dream of a restored kingdom never fully materialized, and Pecario remained a republic. The Restauradores movement lingered until the mid-19th century, after which it ceased to be significant on the political stage.

Despite Pecario’s independence, Manamana functioned as an autonomous region under Iverican control, creating a bitter divide between the two lands. For nearly two centuries, Pecario’s leaders would grapple with the question of Manamana, but the region’s de facto independence and loyalty to Iverica remained unchallenged until much later. In February 1768, the Treaty of San Cristobal signed with Manamana would allow for the mutual recognition of the states and the signing of a mutual peace. The most ardent nationalists secretly hoped that this peace would be only temporary and awaited the return of the Manamana region to the state of Pecario. However, their hopes were in vain, and it would not be until the 1930s that a failed attempt to annex Manamana would take place, definitively burying any illusion of reclaiming the region.

20th century: political instability and coup d’état

The decline in demand for silver and the early labor struggles caused by poor working conditions created a climate of social and political instability during the 1920s in Pecario. President Alonzo Dominguez initiated social reforms and enacted the Constitution of 1924. However, the global economic crisis of 1927 plunged Pecario into recession and social unrest. Governments changed frequently, accompanied by coup d'états. Marco Vanges del Lonto became the de facto president in 1929, suspending elections and governing by decrees, while sending his rival Axel Mayordomo to prison on the Alcazara archipelago, who had participated in the coup d'état of 1928 with him. The poor economic policies and measures taken to mitigate the effects of the global economic crisis had dramatic consequences on the country's mining production, leading to an economic crisis during which Pecario experienced a severe economic downturn.

Vanges resigned in 1934, and political instability intensified with a coup d'état that gave rise to the socialist republic of Pecario, which lasted only eight days before Alonzo Dominguez regained power and stabilized the economy. Alonzo's return helped reduce tensions between political parties. There was also a social crisis; new actors demanded transformations in the way the country was governed. Joaquin Aguirre Cedillo was elected president in 1938 through an alliance opposing the ruling elite. Social and political reforms made Pecario one of the most advanced countries in terms of legislation and social protection. Lithium gradually replaced silver in the national economy (due to global demand). The country industrialized gradually, and the number of workers increased.

The government of Joaquin Aguirre Cedillo achieved various changes, mainly economic, by laying the foundations for Pecario's industrialization through the creation of ONPDPP (National Organization for the Development of Pecario's Production). However, it led to a period of radicalism. Reforms abruptly stopped with the president's death in November 1942. Oriol Díez, with the support of the Communist Party, was elected President.

Governement of Oriol Díez

The economic results of Díez's first year in power appear quite satisfactory: GDP initially progresses strongly, unemployment and inflation decrease; however, the success is deceptive. The following two years will be catastrophic. Inflation explodes, GDP contracts, and the value of the Pecarian currency plummets. The overly expansionary monetary policy is largely responsible for these results, exacerbated by the destabilization of the economy by opponents. The government tries to stem the crisis by fixing commodity prices, which leads to the development of the black market and shortages.

Díez also attempts to gain active support from the population; workers' militias are formed in cities and countryside to maintain the revolutionary legitimacy of the government. Conservative opposition and Christian Democrats mobilize in turn. They organize or contribute to a series of revolts and demonstrations that paralyze the country. At the same time, there is a rise in power of clandestine far-right paramilitary groups. On March 19, 1971, President Díez appoints Arturo Gómez as the Chief General of the Armed Forces following the resignation of Juan de Penezio.

Arturo Gómez's appointment signals the start of a more authoritarian phase in Díez's regime. Gómez, a staunch supporter of Díez's revolutionary ideals, initially uses the military to suppress conservative opposition with increasing brutality. Political freedoms are curtailed, and dissent is met with imprisonment or worse. The regime becomes notorious for its human rights abuses, as the government prioritizes its survival over democratic principles.

Arturo Gómez's appointment as Chief General of the Armed Forces in March 1971 initially solidified Díez's grip on power, as Gómez, a staunch supporter of Díez's revolutionary ideals, used the military to suppress conservative opposition with increasing brutality. Political freedoms were curtailed, and dissent was met with imprisonment or worse. The regime became notorious for its human rights abuses, as the government prioritized its survival over democratic principles.

However, as the economic crisis deepened, tensions between Gómez and Díez began to surface, driven by fundamental disagreements over the direction of the country and personal ambitions. Gómez, a pragmatic military leader with a vision for a more structured and orderly state, grew increasingly frustrated with Díez's erratic and impulsive leadership style. Díez's revolutionary zeal often led to hasty decisions that exacerbated the economic crisis, such as the overly expansionary monetary policy and the disastrous price-fixing measures. Gómez believed these actions were destabilizing the nation and undermining the very revolution they sought to protect.

In private, Gómez began to question Díez's judgment. He saw himself as the true architect of Pecario's future, capable of restoring stability and order through disciplined governance. Díez, on the other hand, viewed Gómez's pragmatic approach as a betrayal of their revolutionary ideals, leading to a widening rift between the two men. Díez's increasingly paranoid behavior also strained their relationship. Fearing coups and betrayals, Díez frequently reshuffled key military positions and interfered with military operations, undermining Gómez's authority. Gómez, who had spent years cultivating loyalty within the armed forces, saw this as a direct affront to his leadership and a hindrance to effective military operations.

Moreover, Gómez's vision of a strong, centralized military role in governance clashed with Díez's attempts to empower civilian militias and revolutionary committees. These groups, often poorly trained and undisciplined, complicated military efforts to maintain order and security. Gómez believed that only a professional, centralized military could bring the stability needed for Pecario to recover from its economic woes.

One of the most significant points of contention was Díez's "Agrarian Reformation" policy. Díez, aiming to consolidate his support among the rural poor, initiated sweeping land reforms that redistributed land from large estates to peasant collectives. While popular among the peasants, these reforms disrupted agricultural production and led to food shortages. Gómez, whose power base included wealthy landowners and conservative elements within the military, saw the agrarian reforms as disastrous. He argued that the reforms were too radical and poorly implemented, leading to economic instability and fueling opposition from the landed elite. This policy became a symbol of Díez's ideological rigidity and his unwillingness to adapt to the nation's pressing economic needs.

Gómez Era (1971-1990)

As the nation's situation grew more dire, Gómez quietly began to distance himself from Díez's increasingly erratic rule. He made secret contact with influential conservative opposition leaders such as Luis Soanio, promising them a return to economic stability and political freedom in exchange for their support. Secret meetings were held in remote locations, and a plan was set in motion to oust Díez from power.

On a the night of October 1971, the plan was executed. Gómez's loyalists seized control of key military installations and communication centers. At dawn, tanks rolled through the streets of the capital, Santa Borbones. The presidential palace was surrounded, and after a brief but intense standoff, Díez was captured. He was subsequently tortured and then executed, and his body was buried in the jungle north of San Luis. A rumor was spread that he had committed suicide out of despair, his remains were excavated only after the fall of the regime in 1994. Gómez addressed the nation, declaring that the reign of tyranny had ended and promising a new era of stability and freedom. Gómez’s takeover was initially met with a mix of fear and cautious optimism. Many Pecarians, exhausted by years of mismanagement and repression, welcomed the change, hoping for a return to stability and democratic governance. However, the power vacuum left by Díez's ouster led to a period of uncertainty.

Gómez, now self-declared President, set about consolidating his rule. He implemented a series of harsh measures aimed at quelling any potential rebellion and rooting out Díez’s supporters. Political purges swept through the government and military, with former loyalists of Díez being imprisoned or exiled. Gómez presented himself as a strongman capable of restoring order, but his promises of political freedom quickly evaporated as he tightened his grip on power. The international community reacted with a mix of cautious engagement and condemnation. Some nations recognized Gómez’s government, hoping for stability, while others imposed sanctions, citing ongoing human rights abuses and the violent nature of the coup. Despite international pressure, Gómez managed to secure financial and military support from a network of authoritarian regimes, bolstering his position.

The economic situation remained dire, but Gómez’s regime began to show signs of improvement. Inflation was slowly brought under control, and with the aid of foreign investments, GDP started to stabilize. However, the drug wars that erupted during Díez’s rule continued to plague the nation. Gómez’s efforts to combat the cartels were met with fierce resistance, leading to ongoing violence and instability. Gómez attempted to portray himself as a populist leader, implementing limited social reforms to appease the masses. Workers' militias, initially formed under Díez, were now co-opted to serve Gómez’s regime, maintaining a semblance of revolutionary legitimacy. Despite these efforts, public discontent simmered beneath the surface, as Gómez’s authoritarian tactics and broken promises of freedom became increasingly apparent.