Oharic language: Difference between revisions

m (fix Europa link) |

m (∆spelling) |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

| states = {{flag|Orioni}} | | states = {{flag|Orioni}} | ||

| region = [[Orient]] | | region = [[Orient]] | ||

| speakers = | | speakers = {{circa}} 120 million | ||

| date = 2018 | | date = 2018 | ||

| familycolor = Europan | | familycolor = Europan | ||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

}} | }} | ||

'''Oharic''' (/ɒːˈhɑːrɪk/) is a Europan language belonging to the Yuro-Oriental branch, predominantly spoken in Orioni. Ranking as one of the foremost Yuro-Oriental languages in the region, Oharic holds significant linguistic prominence in [[Orioni]], where it is not only widely spoken but also deeply entrenched in the sociocultural fabric. Several regions within the imperial system have adopted Oharic either as their official language or as a working language, attesting to its widespread influence. The dialectical landscape of Oharic is marked by two principal dialects: the standard Oharic, which has its roots in the western regions, and the [[#Meharic|Meharic]], originating from the eastern territories. | |||

Historically, the prestige and cultural significance of the Oharic language have been evident since the reign of [[Empress Hideto]] in 1270. The imperial court, especially the renowned ‘[[Anahita]] line’ of queens originating from the historical [[O'polis]] province, not only spoke but also promoted the Oharic culture. By the late 12th century, Oharic had become the predominant language in courts, commerce, daily interactions, military affairs, and even the sacred rituals of the [[Elitism|Elite Church]]. Even today, it retains its position as Orioni's second language. According to the 2007 census, while almost a quarter (22%) of [[Orinese people]] are native speakers of Oharic, an overwhelming 96% have proficiency as secondary speakers. The influence of Oharic transcends national boundaries, with approximately 3 million emigrants outside Orioni continuing to communicate in the language. Notably, the Amisti communities spread across the broader region of [[Europa (continent)|Europa]] predominantly converse in Oharic. Religiously, Ancient Oharic holds a sanctified position within the [[Amisti]] faith, being revered as a holy language. Its sacred status ensures that it resonates among Amisti followers globally. Geographically, Oharic stands out as the dominant language in [[Orient]]al Europa. From a scriptural standpoint, Oharic adopts the Aroman script and is conventionally written from left to right. | |||

== History == | |||

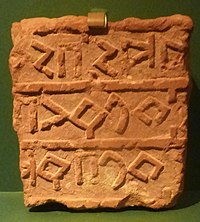

[[File:Dadanitic tablet - 20180430.jpg|200px|thumb|left|Ancient Oharic script on a tablet.]] | |||

The origin of the Oharic language can be traced back to what is now referred to as “Ancient Oharic.” This archaic form, sometimes known as “Uharic” or “Uwaric,” provided the foundational structure upon which the language developed. Evidence for its ancient usage, as depicted on the tablet to the left, underscores its historical prominence and cultural significance. | |||

By the end of the first millennium, a shift in linguistic patterns led to the emergence of “Middle Oharic.” This transition marked a distinct evolutionary phase in the language, characterized by an expansion in vocabulary, and a refinement in grammatical structures. These changes were likely influenced by increased interactions with neighbouring cultures and the spread of literature. | |||

“Common Oharic” emerged in the subsequent centuries, reflecting a more standardized version of the language. This form came into prominence due to its widespread use in administration, trade, and scholarly works across the region of Orioni. The pervasive nature of Common Oharic solidified its position as the mainstay dialect and served as the bridge between its ancient origins and its contemporary form. | |||

The “Meharic” dialect presents an intriguing offshoot of the Oharic linguistic tree. Rooted in the community of Medani, Meharic was not just a mere dialectical variant, but more the result of an incomplete linguistic transition. As Orioni's urban centres and the elite adopted Oharic, Meharic became predominant in rural settings, bearing a unique linguistic character without an extensive literary tradition. The 20th century saw a resurgence of regional languages, and with it, a rejuvenation of Meharic, which was revered for its cultural authenticity. | |||

Oharic | In tracing the progression from Ancient Oharic to its modern descendants, one witnesses not just linguistic evolution, but also the shifting tides of culture, politics, and society throughout the ages in Orioni. | ||

==Grammar== | == Grammar == | ||

Oharic nouns can have a masculine or feminine gender. There are several ways to express gender. An example is the old suffix -t for femininity. This suffix is no longer productive and is limited to certain patterns and some isolated nouns. Nouns and adjectives ending in -awi usually take the suffix -t to form the feminine form, e.g. ityop̣p̣ya-(a)wi 'Orioni (m.)' vs. ityop̣p̣ya-wi-t 'Orioni (f.)'; sämay-awi 'heavenly (m.)' vs. sämay-awi-t 'heavenly (f.)'. This suffix also occurs in nouns and adjective based on the pattern qǝt(t)ul, e.g. nǝgus 'king' vs. nǝgǝs-t 'Queen' and qǝddus 'holy (m.)' vs. qǝddǝs-t 'holy (f.)'. | Oharic nouns can have a masculine or feminine gender. There are several ways to express gender. An example is the old suffix -t for femininity. This suffix is no longer productive and is limited to certain patterns and some isolated nouns. Nouns and adjectives ending in -awi usually take the suffix -t to form the feminine form, e.g. ityop̣p̣ya-(a)wi 'Orioni (m.)' vs. ityop̣p̣ya-wi-t 'Orioni (f.)'; sämay-awi 'heavenly (m.)' vs. sämay-awi-t 'heavenly (f.)'. This suffix also occurs in nouns and adjective based on the pattern qǝt(t)ul, e.g. nǝgus 'king' vs. nǝgǝs-t 'Queen' and qǝddus 'holy (m.)' vs. qǝddǝs-t 'holy (f.)'. | ||

==Orthography== | == Orthography == | ||

Oharic is written in the Aroman alphabet. There are two competing orthographies. The | Oharic is written in the Aroman alphabet. There are two competing orthographies. The “old” orthography was introduced by Occidental missionaries. This system is not highly consistent or faithful in representing the sounds of Oharic, but until recently, it had no competing orthography. It is currently widely used, including in newspapers and signs. The “new” orthography is gaining popularity, especially in schools and among young adults and children. The “new” orthography represents the sounds of the Oharic language more faithfully and is the system used in the Oharic–Anglish dictionary. | ||

Both systems already require fonts that display Basic Aroman (with A a B b D d E e I i J j K k L l M m N n O o P p R r T t U u W w) and Aroman Extended-A (with Ā ā Ō ō Ū ū). The standard orthography also requires Spacing Modifier Letters for the combining diacritics. The MOD's alternative letters have the advantage of being neatly displayable as all-precomposed characters in any Unicode fonts that support Basic Aroman, Aroman Extended-A along with Aroman-1 Supplement (with Ñ ñ) and Aroman Extended Additional (with Ḷ ḷ Ṃ ṃ Ṇ ṇ Ọ ọ). | Both systems already require fonts that display Basic Aroman (with A a B b D d E e I i J j K k L l M m N n O o P p R r T t U u W w) and Aroman Extended-A (with Ā ā Ō ō Ū ū). The standard orthography also requires Spacing Modifier Letters for the combining diacritics. The MOD's alternative letters have the advantage of being neatly displayable as all-precomposed characters in any Unicode fonts that support Basic Aroman, Aroman Extended-A along with Aroman-1 Supplement (with Ñ ñ) and Aroman Extended Additional (with Ḷ ḷ Ṃ ṃ Ṇ ṇ Ọ ọ). | ||

==Vocabulary== | == Vocabulary == | ||

The richness of the Oharic language can be appreciated through a comparison of basic vocabulary with its [[Anglish language|Anglish]] counterparts. The Meharic dialect occasionally offers variations to the standard Oharic terms, underscoring the diverse linguistic landscape of [[Orioni]]. | |||

=== Numbers === | |||

The table below illustrates the cardinal numbers from one through ten in both [[Anglish language|Anglish]] and Oharic. Notably, for some numbers, the [[Meharic language|Meharic]] forms differ from standard Oharic, highlighting subtle regional variations within the language. | |||

{| class= | {| class='wikitable' | ||

|- | |- | ||

! !! Anglish numbers !! Oharic (Meharic) | ! !! Anglish numbers !! Oharic (Meharic) | ||

| Line 87: | Line 96: | ||

|} | |} | ||

Weekdays | === Weekdays === | ||

{| class= | Weekdays form a vital part of any language, helping structure our daily lives. Below, the [[Anglish language|Anglish]] weekdays are compared with their Oharic counterparts. Again, where the Meharic dialect diverges, it is duly noted. | ||

{| class='wikitable' | |||

|- | |- | ||

! Anglish weekdays !! Oharic (Meharic) | ! Anglish weekdays !! Oharic (Meharic) | ||

| Line 108: | Line 119: | ||

|} | |} | ||

Months | === Months === | ||

{| class= | The names of the months often hold historical or cultural significance, and their etymology can provide insights into a society's traditions or cosmology. Here, the [[Anglish language|Anglish]] months are paralleled with the Oharic equivalents, allowing for a more profound understanding of the cultural context from which they arise. | ||

{| class='wikitable' | |||

|- | |- | ||

! Anglish months !! Oharic | ! Anglish months !! Oharic | ||

| Line 139: | Line 152: | ||

|} | |} | ||

Continents | === Continents === | ||

A study of continental names in various languages can reveal influences of trade, exploration, or colonization. The following table compares the [[Anglish language|Anglish]] names of continents with their Oharic translations. These names provide a window into how the Oharic-speaking people perceive and relate to the broader world around them. | |||

{| class= | {| class='wikitable' | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Anglish continents !! Oharic | ! Anglish continents !! Oharic | ||

| Line 151: | Line 166: | ||

| [[Argis]] || Ārigosi | | [[Argis]] || Ārigosi | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[Aurelia]] || | | [[Aurelia]] || Owirēliye | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[Europa (continent)]] || Erwaba | | [[Europa (continent)|Europa]] || Erwaba | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[Marenesia]] || Marinēsīye | | [[Marenesia]] || Marinēsīye | ||

| Line 160: | Line 175: | ||

|} | |} | ||

==Dialects== | == Dialects == | ||

=== Meharic === | |||

The Meharic dialect represents a unique linguistic branch within the Oharic language family, primarily spoken by the descendants of [[Medani]]. While it's typically understood as a form of Oharic, historical linguists suggest that Meharic might not have evolved as a full-fledged dialect of Oharic from the outset. Instead, it seems to have developed due to incomplete language acquisition processes when the Medani community transitioned from their native Meharic tongue to adopting Oharic. | |||

During certain historical periods, Oharic gained prominence, especially in urban settings and among the elite. It became synonymous with the cities and the upper echelons of society. In contrast, Meharic was largely confined to rural areas and did not have a robust literary tradition, which furthered its status as a more regional or colloquial tongue. | |||

However, the 20th century ushered in a significant sociolinguistic shift. The aftermath of colonialism brought about a renewed sense of regional pride, intertwined with reflections on the diminishing empire and a collective sense of identity reevaluation. There was a gradual but undeniable paradigm shift wherein languages besides the standard Oharic began to be reassessed. A newfound appreciation emerged for regional traditions, languages, and dialects. This socio-cultural movement facilitated the resurgence of the Meharic language, positioning it as a potent tool for social, cultural, and even political expression, especially following the period often referred to as the “dark centuries.” During this epoch, the dominance of Oharic overshadowed other dialects to such an extent that they nearly vanished from the collective consciousness.{{efn|OOC. This historical trajectory draws inspiration from the {{wp|Rexurdimento}} of the Galician language in Spain.}} | |||

A noteworthy aspect of the Meharic dialect is its distinctive phonetic structure, especially evident when dealing with stems that commence with a vowel. In Meharic, there's a repetition of the initial consonant before the vowel. In contrast, Oharic uses an intervening vowel to delineate the consonants. For instance, the stem ''aweti'' (denoting “play”) is articulated as ''waweti'' in Meharic, but it remains unchanged as ''aweti'' in standard Oharic | |||

=== | == Notes == | ||

{{Notelist}} | |||

{{Orioni}} | {{Orioni}} | ||

{{Eurth}} | {{Eurth}} | ||

[[Category:Languages]] | [[Category:Languages]] | ||

[[Category:Language (Eurth)]] | |||

Latest revision as of 20:59, 22 November 2024

| Oharic | |

|---|---|

Religious document in Middle Oharic script. | |

| Native to | |

| Region | Orient |

Native speakers | c. 120 million (2018) |

Europan

| |

Early forms | |

Standard forms | Common Oharic

|

| Dialects | |

| Aroman | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Imperial Academy |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | oh |

| ISO 639-2 | oha |

| ISO 639-3 | oha |

Areas with significant numbers of Oharic speakers (including dialects) | |

Oharic (/ɒːˈhɑːrɪk/) is a Europan language belonging to the Yuro-Oriental branch, predominantly spoken in Orioni. Ranking as one of the foremost Yuro-Oriental languages in the region, Oharic holds significant linguistic prominence in Orioni, where it is not only widely spoken but also deeply entrenched in the sociocultural fabric. Several regions within the imperial system have adopted Oharic either as their official language or as a working language, attesting to its widespread influence. The dialectical landscape of Oharic is marked by two principal dialects: the standard Oharic, which has its roots in the western regions, and the Meharic, originating from the eastern territories.

Historically, the prestige and cultural significance of the Oharic language have been evident since the reign of Empress Hideto in 1270. The imperial court, especially the renowned ‘Anahita line’ of queens originating from the historical O'polis province, not only spoke but also promoted the Oharic culture. By the late 12th century, Oharic had become the predominant language in courts, commerce, daily interactions, military affairs, and even the sacred rituals of the Elite Church. Even today, it retains its position as Orioni's second language. According to the 2007 census, while almost a quarter (22%) of Orinese people are native speakers of Oharic, an overwhelming 96% have proficiency as secondary speakers. The influence of Oharic transcends national boundaries, with approximately 3 million emigrants outside Orioni continuing to communicate in the language. Notably, the Amisti communities spread across the broader region of Europa predominantly converse in Oharic. Religiously, Ancient Oharic holds a sanctified position within the Amisti faith, being revered as a holy language. Its sacred status ensures that it resonates among Amisti followers globally. Geographically, Oharic stands out as the dominant language in Oriental Europa. From a scriptural standpoint, Oharic adopts the Aroman script and is conventionally written from left to right.

History

The origin of the Oharic language can be traced back to what is now referred to as “Ancient Oharic.” This archaic form, sometimes known as “Uharic” or “Uwaric,” provided the foundational structure upon which the language developed. Evidence for its ancient usage, as depicted on the tablet to the left, underscores its historical prominence and cultural significance.

By the end of the first millennium, a shift in linguistic patterns led to the emergence of “Middle Oharic.” This transition marked a distinct evolutionary phase in the language, characterized by an expansion in vocabulary, and a refinement in grammatical structures. These changes were likely influenced by increased interactions with neighbouring cultures and the spread of literature.

“Common Oharic” emerged in the subsequent centuries, reflecting a more standardized version of the language. This form came into prominence due to its widespread use in administration, trade, and scholarly works across the region of Orioni. The pervasive nature of Common Oharic solidified its position as the mainstay dialect and served as the bridge between its ancient origins and its contemporary form.

The “Meharic” dialect presents an intriguing offshoot of the Oharic linguistic tree. Rooted in the community of Medani, Meharic was not just a mere dialectical variant, but more the result of an incomplete linguistic transition. As Orioni's urban centres and the elite adopted Oharic, Meharic became predominant in rural settings, bearing a unique linguistic character without an extensive literary tradition. The 20th century saw a resurgence of regional languages, and with it, a rejuvenation of Meharic, which was revered for its cultural authenticity.

In tracing the progression from Ancient Oharic to its modern descendants, one witnesses not just linguistic evolution, but also the shifting tides of culture, politics, and society throughout the ages in Orioni.

Grammar

Oharic nouns can have a masculine or feminine gender. There are several ways to express gender. An example is the old suffix -t for femininity. This suffix is no longer productive and is limited to certain patterns and some isolated nouns. Nouns and adjectives ending in -awi usually take the suffix -t to form the feminine form, e.g. ityop̣p̣ya-(a)wi 'Orioni (m.)' vs. ityop̣p̣ya-wi-t 'Orioni (f.)'; sämay-awi 'heavenly (m.)' vs. sämay-awi-t 'heavenly (f.)'. This suffix also occurs in nouns and adjective based on the pattern qǝt(t)ul, e.g. nǝgus 'king' vs. nǝgǝs-t 'Queen' and qǝddus 'holy (m.)' vs. qǝddǝs-t 'holy (f.)'.

Orthography

Oharic is written in the Aroman alphabet. There are two competing orthographies. The “old” orthography was introduced by Occidental missionaries. This system is not highly consistent or faithful in representing the sounds of Oharic, but until recently, it had no competing orthography. It is currently widely used, including in newspapers and signs. The “new” orthography is gaining popularity, especially in schools and among young adults and children. The “new” orthography represents the sounds of the Oharic language more faithfully and is the system used in the Oharic–Anglish dictionary.

Both systems already require fonts that display Basic Aroman (with A a B b D d E e I i J j K k L l M m N n O o P p R r T t U u W w) and Aroman Extended-A (with Ā ā Ō ō Ū ū). The standard orthography also requires Spacing Modifier Letters for the combining diacritics. The MOD's alternative letters have the advantage of being neatly displayable as all-precomposed characters in any Unicode fonts that support Basic Aroman, Aroman Extended-A along with Aroman-1 Supplement (with Ñ ñ) and Aroman Extended Additional (with Ḷ ḷ Ṃ ṃ Ṇ ṇ Ọ ọ).

Vocabulary

The richness of the Oharic language can be appreciated through a comparison of basic vocabulary with its Anglish counterparts. The Meharic dialect occasionally offers variations to the standard Oharic terms, underscoring the diverse linguistic landscape of Orioni.

Numbers

The table below illustrates the cardinal numbers from one through ten in both Anglish and Oharic. Notably, for some numbers, the Meharic forms differ from standard Oharic, highlighting subtle regional variations within the language.

| Anglish numbers | Oharic (Meharic) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | One | Ānidi (Nanadi) |

| 2 | Two | Huleti |

| 3 | Three | Sositi |

| 4 | Four | Ārati (Rarati) |

| 5 | Five | Āmisiti (Mamisiti) |

| 6 | Six | Sidisiti |

| 7 | Seven | Sebati |

| 8 | Eight | Simiti |

| 9 | Nine | Zet’enyi |

| 10 | Ten | Āsiri (Sariri) |

Weekdays

Weekdays form a vital part of any language, helping structure our daily lives. Below, the Anglish weekdays are compared with their Oharic counterparts. Again, where the Meharic dialect diverges, it is duly noted.

| Anglish weekdays | Oharic (Meharic) |

|---|---|

| Monday | Senyo |

| Tuesday | Makisenyo |

| Wednesday | Irobi (Rirobi) |

| Thursday | Hāmusi |

| Friday | Āribi (Raribi) |

| Saturday | K’idamē |

| Sunday | Ihudi (Hihudi) |

Months

The names of the months often hold historical or cultural significance, and their etymology can provide insights into a society's traditions or cosmology. Here, the Anglish months are paralleled with the Oharic equivalents, allowing for a more profound understanding of the cultural context from which they arise.

| Anglish months | Oharic |

|---|---|

| January | T’iri |

| February | Yekatīti |

| March | Megabīti |

| April | Mīyazīya |

| May | Giniboti |

| June | Senē |

| July | Hāmilē |

| August | Neḥāsē |

| September | Mesikeremi |

| October | T’ik’imiti |

| November | Hidari |

| December | Tahisasi |

Continents

A study of continental names in various languages can reveal influences of trade, exploration, or colonization. The following table compares the Anglish names of continents with their Oharic translations. These names provide a window into how the Oharic-speaking people perceive and relate to the broader world around them.

| Anglish continents | Oharic |

|---|---|

| Alharu | Āli-hāroni |

| Antargis | Ānitarigīsi |

| Argis | Ārigosi |

| Aurelia | Owirēliye |

| Europa | Erwaba |

| Marenesia | Marinēsīye |

| Thalassa | Talisa |

Dialects

Meharic

The Meharic dialect represents a unique linguistic branch within the Oharic language family, primarily spoken by the descendants of Medani. While it's typically understood as a form of Oharic, historical linguists suggest that Meharic might not have evolved as a full-fledged dialect of Oharic from the outset. Instead, it seems to have developed due to incomplete language acquisition processes when the Medani community transitioned from their native Meharic tongue to adopting Oharic.

During certain historical periods, Oharic gained prominence, especially in urban settings and among the elite. It became synonymous with the cities and the upper echelons of society. In contrast, Meharic was largely confined to rural areas and did not have a robust literary tradition, which furthered its status as a more regional or colloquial tongue.

However, the 20th century ushered in a significant sociolinguistic shift. The aftermath of colonialism brought about a renewed sense of regional pride, intertwined with reflections on the diminishing empire and a collective sense of identity reevaluation. There was a gradual but undeniable paradigm shift wherein languages besides the standard Oharic began to be reassessed. A newfound appreciation emerged for regional traditions, languages, and dialects. This socio-cultural movement facilitated the resurgence of the Meharic language, positioning it as a potent tool for social, cultural, and even political expression, especially following the period often referred to as the “dark centuries.” During this epoch, the dominance of Oharic overshadowed other dialects to such an extent that they nearly vanished from the collective consciousness.[a]

A noteworthy aspect of the Meharic dialect is its distinctive phonetic structure, especially evident when dealing with stems that commence with a vowel. In Meharic, there's a repetition of the initial consonant before the vowel. In contrast, Oharic uses an intervening vowel to delineate the consonants. For instance, the stem aweti (denoting “play”) is articulated as waweti in Meharic, but it remains unchanged as aweti in standard Oharic

Notes

- ↑ OOC. This historical trajectory draws inspiration from the Rexurdimento of the Galician language in Spain.